A wobbly market prompts Maynard Paton to search for potential ‘safe havens’. Filters for net cash, high margins and a pandemic-defiant dividend lead to vinyl flooring specialist James Halstead.

Recent market wobbles have prompted some ‘back to basics’ filtering.

Hence a new screen to identify companies that have strong balance sheets, robust margins and a dividend that has defied the pandemic.

The exact filter criteria I applied for this ‘safe haven’ search were:

- Net borrowings less total leases of no more than 0 (i.e. a net cash position excluding IFRS 16 lease obligations);

- A trailing 12-month operating margin of 15% or more, and;

- A minimum five-year record of annual dividend improvements.

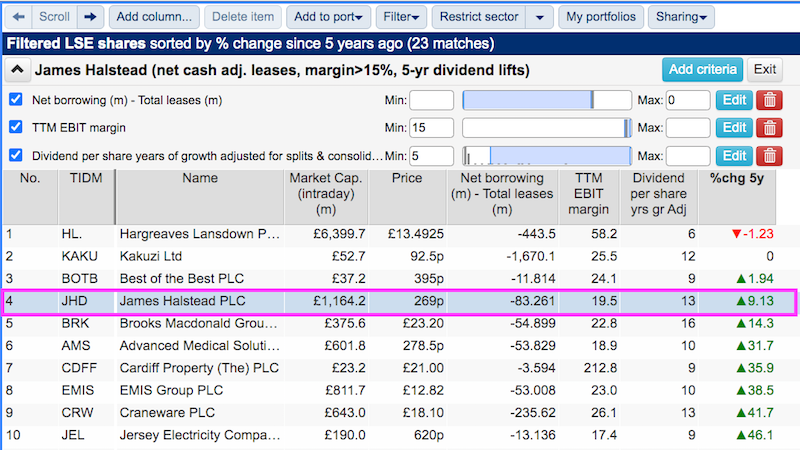

I ran the screen the other day and SharePad returned 23 matches:

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 23/02/22: James Halstead” filter within SharePad’s jumbo Filter Library. My instructions show you how.)

Among the 23 matches were Best of the Best, Dotdigital, Fever-Tree Drinks, Hargreaves Lansdown, Impax Asset Management and Jarvis Securities.

I added an extra column to the screening results to sort the 23 on five-year share-price performance.

I selected James Halstead because its shares had improved only 9% since February 2017. Of the three weaker performers, two had already been subject to my SharePad microscope while the third — an obscure Kenyan agricultural business — did not quite fit the ‘safe haven’ approach.

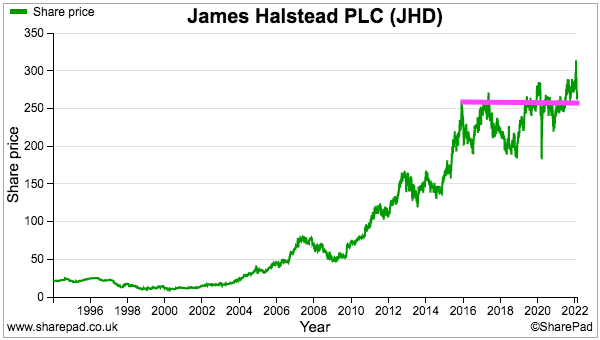

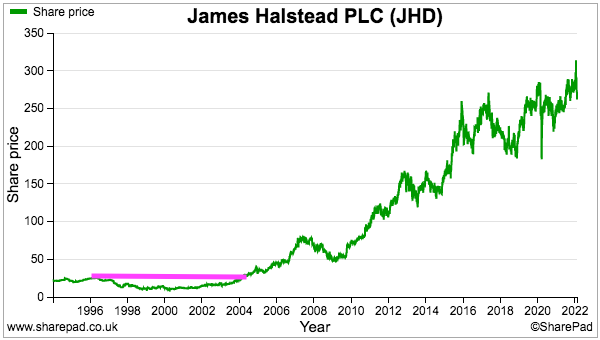

SharePad shows Halstead’s shares having 29-bagged from the 9p low of 2000. The shares now trade close to the level first reached during late 2015:

Let’s take a closer look.

The history of James Halstead

This story commences during 1915 in Radcliffe near Manchester. Founder James Halstead started a business waxing and waterproofing coats using four weaving machines and paying three employees the equivalent of £1.60 for a 54-hour week.

This super 13-minute video recounts how the company subsequently emerged as a leading manufacturer of vinyl flooring that today still operates at the same Radcliffe site.

The major turning point occurred when the company hired “pioneering chemist” Bill Roberts during the late 1940s. His work led to a new vinyl flooring that quickly disrupted the market for linoleum. The new flooring became poplar because of its greater durability and wide range of colours.

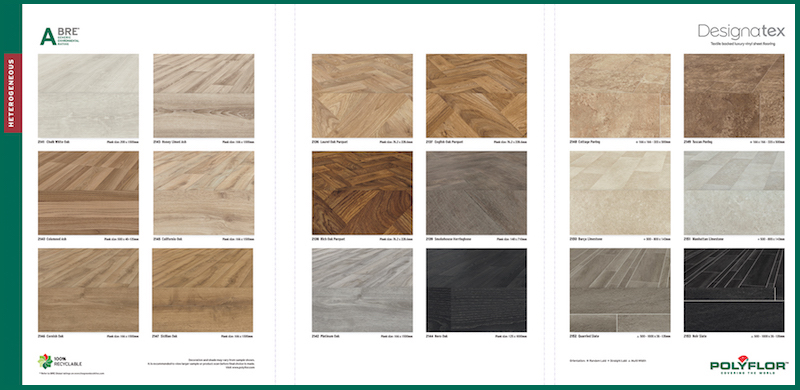

These days Halstead is best known for Polyflor, a commercial floor-covering used in a variety of buildings such as offices, hospitals, schools, sports centres, shops and airports. Purchasers are attracted by the group’s quality manufacturing, stock availability, comprehensive range and expert support.

Halstead floated during 1948 and the Halstead family continues to lead the business today. Sons of founder James — John and Herbert — took charge during 1935 while Geoffrey Halstead, son of John, led the business from 1974. Geoffrey’s son Mark Halstead became the top executive during 2011.

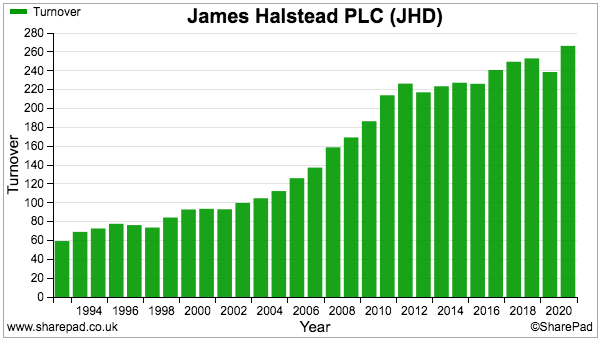

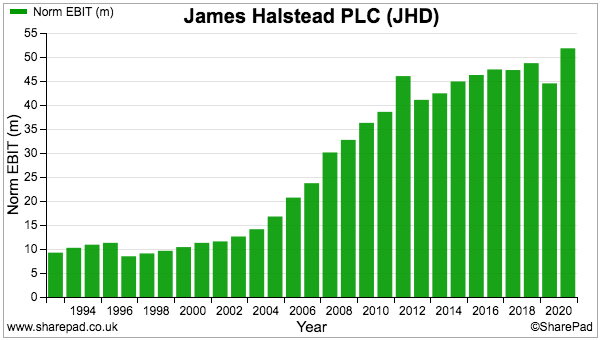

Companies House shows sales of £9 million and profit of £439k when Geoffrey Halstead took charge, while SharePad shows revenue and profit having since surged to £266 million and £51 million respectively:

International efforts have commendably supported the company’s progress; sales outside the UK have grown from 29% to 63% of total revenue during the last 30 years. The business did not suffer too badly during the pandemic, with the dividend lifted 2% despite profit falling 9% during 2020.

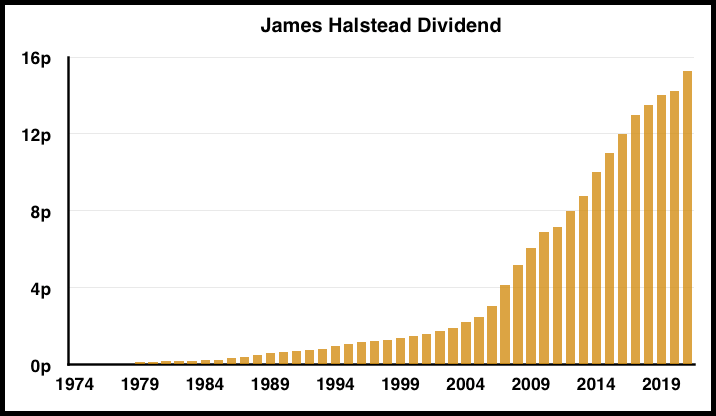

Halstead’s dividend is in fact among the market’s most dependable. My own spreadsheet shows the ordinary payout being lifted every year since 1976:

Shareholders have also collected numerous special dividends along the way, including extra payments during 2007, 2010, 2013 and 2016.

Halstead’s SharePad summary

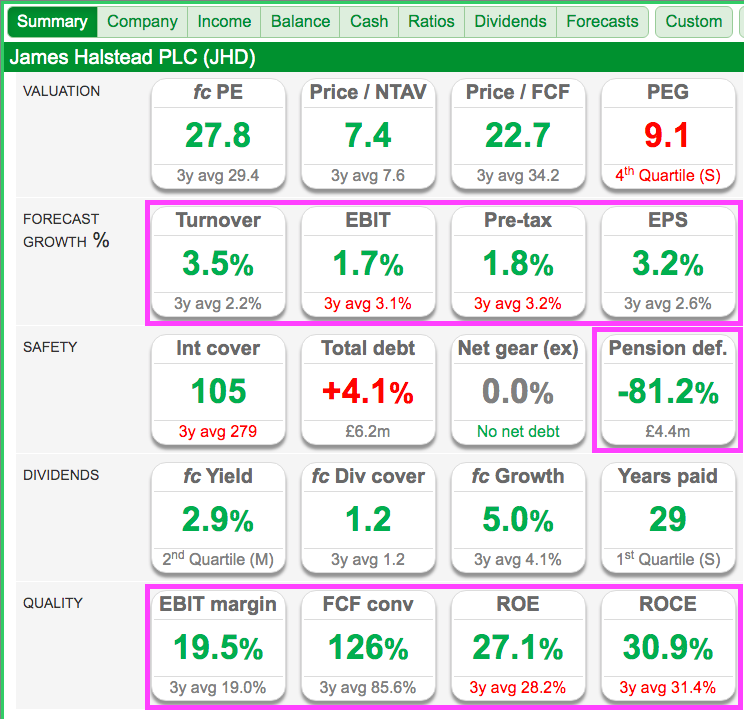

The SharePad Summary for Halstead is shown below:

I see the bottom row reveals some very attractive numbers, but I note a pension deficit in the middle row. And the growth forecasts on the second row appear very pedestrian.

Let’s start with the ‘quality’ ratios.

Margin and cash conversion

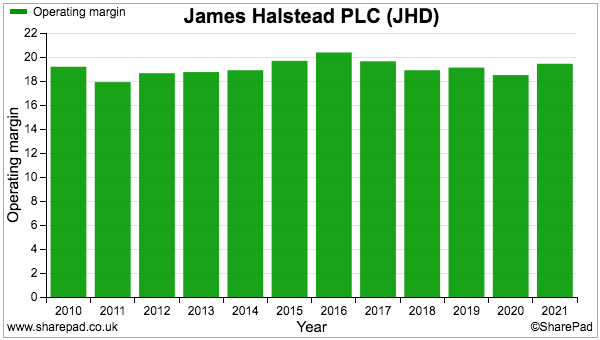

A consistently attractive 18% margin suggests customers are prepared to pay a healthy premium for Halstead’s flooring and service:

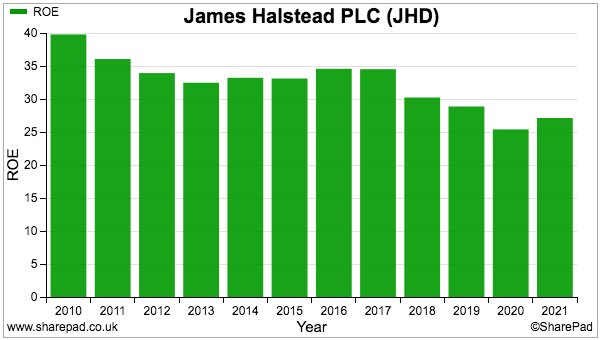

Return on equity (ROE) has meanwhile topped a wonderful 25%, although the trend during recent years has been downwards:

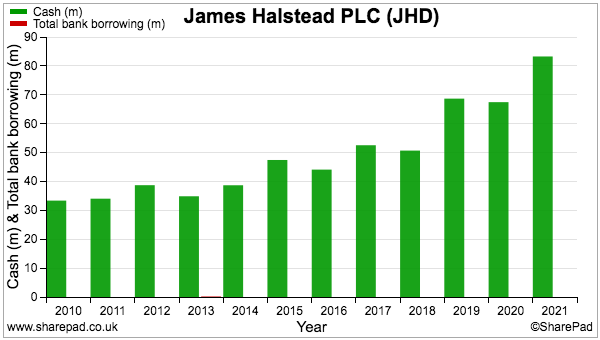

One reason for the reduced ROE is Halstead’s bumper bank balance.

Cash in the bank represents more than half of the company’s net asset value and provides investors with plenty of reassurance… but delivers very little in the way of direct earnings. The business has operated with a net cash position for decades and cash has nearly doubled to £83 million since 2016:

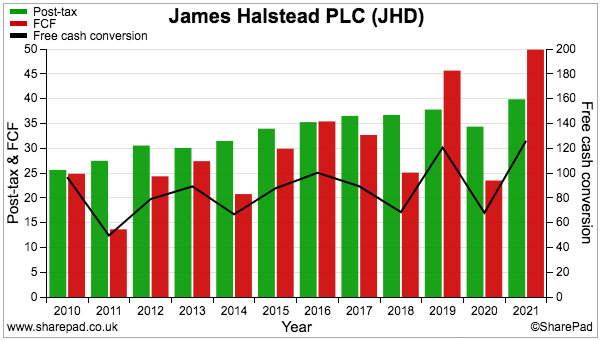

The burgeoning cash position is the result of some very useful cash generation. The chart below shows reported earnings converting at an average 94% (black line, right axis) into free cash during the last five years:

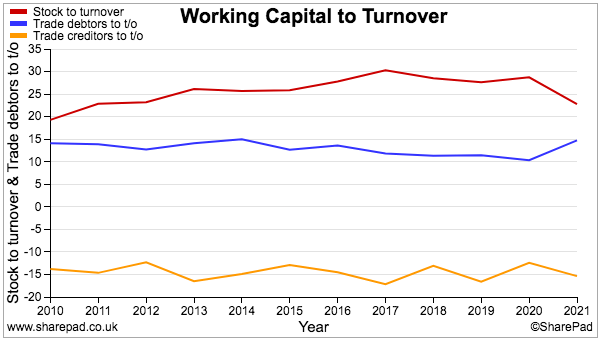

Cash conversion has been assisted by reasonably consistent control of stock, debtors and creditors:

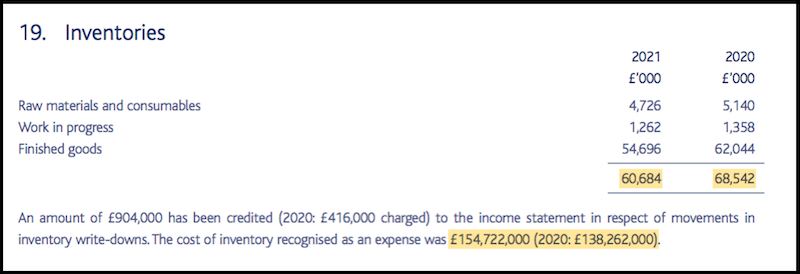

Stock levels advanced from 20% to 30% of revenue between 2010 and 2020, while Halstead explained the drop for 2021 was due to a “lack of availability of raw materials“.

Halstead has said extra “shop-floor labour” had been taken on to raise stock levels, because a good amount of available product can in fact become a “key differentiator“:

“For many years as a manufacturer we have committed to stock in the warehouse to smooth production pressures and to be able to supply large projects “off the shelf” rather than make to order. It is a key differentiator of our business and it can have its challenges but in this year it was a key strength.”

The 2021 annual report shows stock valued at £155 million was expensed during the year. Carrying stock of £61 million therefore suggests goods wait in the warehouse for an average of almost five months (61/155*12 months):

The comparable warehouse wait for 2018, 2019 and 2020 was exactly six months, which does feel a long time. Mind you, the risk of stock write-downs may be limited as vinyl flooring does not seem the type of product that can become obsolete overnight.

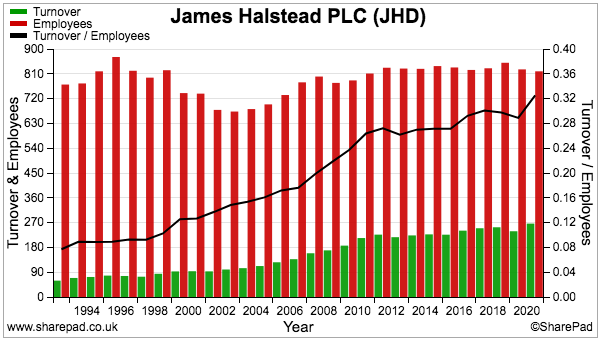

Perhaps the most impressive SharePad chart for Halstead is the one below showing revenue per employee:

During the last 30 years, the workforce has remained around the 800 mark while revenue has more than quadrupled to £266 million.

Revenue per employee at £325k is extremely impressive for a manufacturing business, and underlines the notion that customers are happy to pay a healthy premium for the group’s flooring.

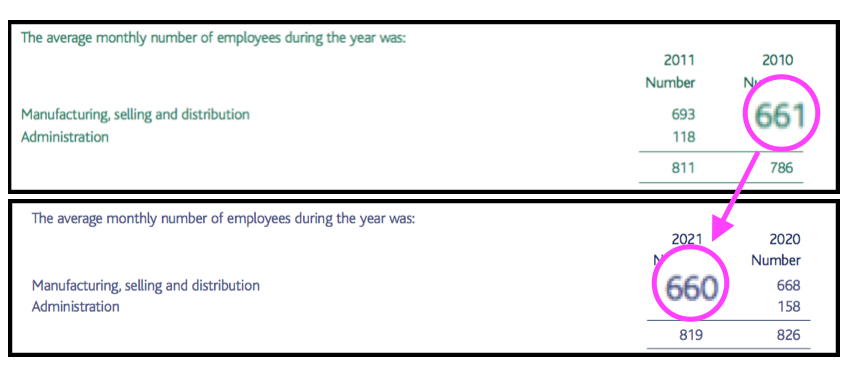

Also of interest is revenue per employee moving higher despite little overall change to the number of manufacturing, selling and distribution staff. Between 2010 and 2021, such ‘hands on’ workers have stayed around the 660 mark:

Halstead has clearly discovered efficiencies within its manufacturing processes. Greater staff productivity may also relate to a contented workforce; that earlier video referred to employee ‘clubs’ for workers with 25-year and 40-year tenures.

Pension deficit

Halstead’s financials for the last 15 years show no acquisitions, no restatements and no adjustments, and are therefore among the most straightforward I have reviewed for SharePad.

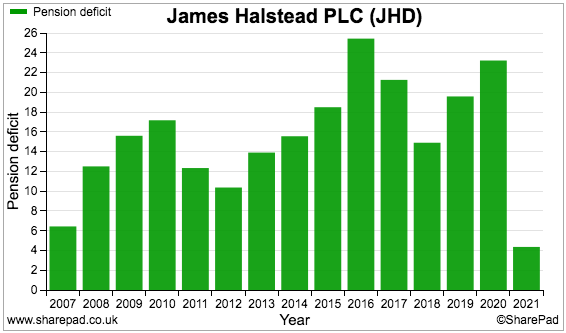

But the books are not perfect and the aforementioned pension deficit in particular requires some inspection:

The scheme’s reported shortfall has bobbed between £4 million and £25 million and looks typical of a final-salary plan — that is, the deficit never seems to go away no matter how much money is injected into the fund.

But Halstead’s funding gap appears manageable to me using the approach described in my Norcros article.

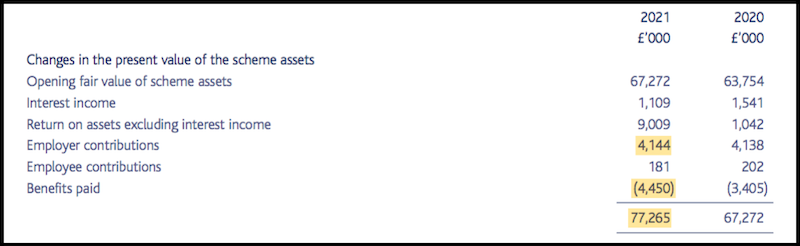

Plan assets of £77 million appear appropriate with benefits perhaps running at £4 million a year and company contributions also running at £4 million a year:

Note that contributions to the scheme have increased over time. For the five years to 2021, Halstead contributed £14 million… yet for the five years before that the total was £10 million and the five years before that the total was £6 million.

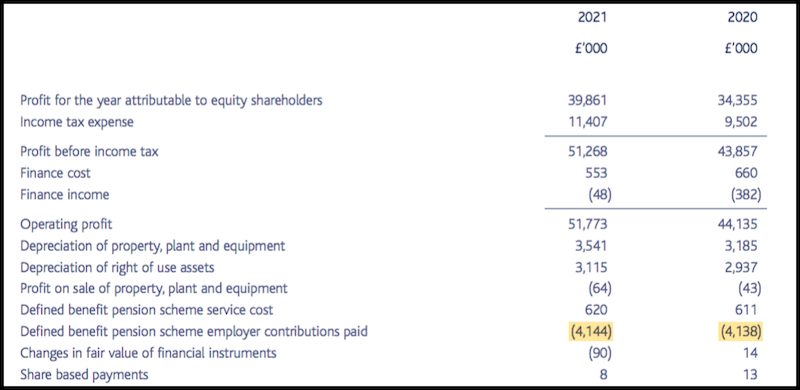

Note, too, that Halstead’s pension contributions effectively bypass the income statement by showing up as negative entries within the cash flow statement:

I calculate Halstead’s aggregate reported operating profit for the last five years would have been reduced by 6% had the pension contributions been recognised as an operating expense.

Regarding future payments, Halstead’s annual report confirmed a “new deficit reduction plan was agreed in July 2021” and “normal” contributions of £2 million were expected for 2022. The report also included the following paragraph that I did not really understand:

“The board has discussed with the trustees the future accrual of benefits and the trustees made clear that an equitable payment by members would see an increase in member contributions of around 12-15%.”

Management and corporate reporting

Quoted ‘family’ firms tend to have governance quirks and Halstead is no exception.

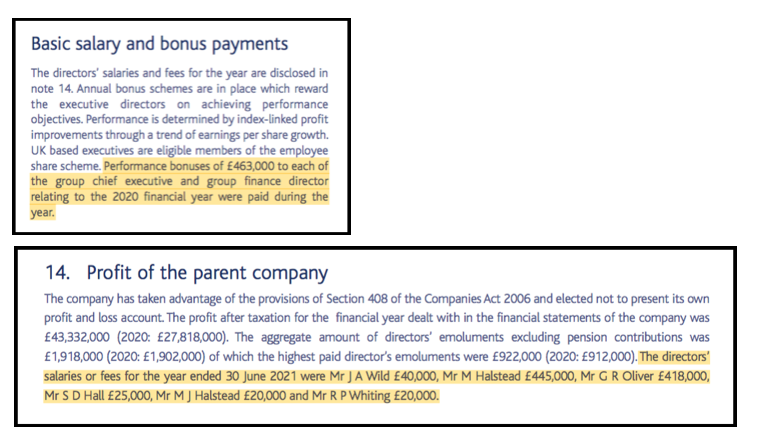

The company’s remuneration reporting is very poor for a business that boasted earnings of £40 million last year. Rather than present the standard table listing each director’s pay and bonuses, Halstead instead spreads the details around the annual-report small-print:

The footnote disclosures certainly give the impression of something to hide, and I note bonuses have been paid to boss Mark Halstead and the finance director every year since at least 2010. Bonuses typically represent 100% of executive salaries and the annual report reveals only the following as to how the bonuses are decided:

“Annual bonus schemes are in place which reward the executive directors on achieving performance objectives. Performance is determined by index-linked profit improvements through a trend of earnings per share growth.”

Individual remuneration at £900k-plus no doubt reflects the executives’ long experience. Mark Halstead and the finance director have both served as board executives for more than 20 years and must take credit for extending that illustrious run of dividends.

The board does offer a degree of cosiness, with the present chairman employed as the group’s external auditor up until the early 1990s and having served as a non-exec since 2001.

Of the other non-execs, one is a Halstead family member while another has served for ten years, which leaves only one non-exec (board tenure: five years) who could be deemed ‘independent’.

(Former Halstead non-execs include prominent private investor Lord Lee of Trafford, who joined the board during 2000 but failed to be re-elected at the AGM later that year)

Various trusts and unclear disclosures make deriving the Halstead family’s shareholding rather difficult.

But the company’s website says 30% of the shares are not in public hands, which could mean the family owns 30% and as such enjoys a £350 million collective investment. The annual report confirms chief exec Mark Halstead boasts a 6%/£70 million personal shareholding. Board options are minimal.

Perhaps the main question concerning management is succession: there is no obvious replacement for boss Mark Halstead, who turns 65 later this year.

A veteran Halstead shareholder has told me: “Mark Halstead is a class act… [but] I do not believe there is a credible family replacement“.

I must admit this scuttlebutt surprised me. I had assumed a fifth-generation Halstead was waiting in the wings to take over. The annual report describes succession planning only as an “ongoing topic of discussion.”

Valuation and summary

Halstead’s statement the other week was not awful but did not set high expectations either for next month’s interims:

“The backdrop to manufacturing remained challenging with the resurgence of the Covid-19 virus disrupting manning levels and the widely reported delays and increased costs of international freight. In addition, raw material availability has continued to be restricted and costs increased.

Nevertheless, sales demand has continued to be strong… and turnover for the six months will be higher than last year.

Given the increased costs of materials, freight and energy that have prevailed and the inevitable time lag in reflecting these costs in prices it is to be expected that profit has been affected in the first six months results to a marginal extent.”

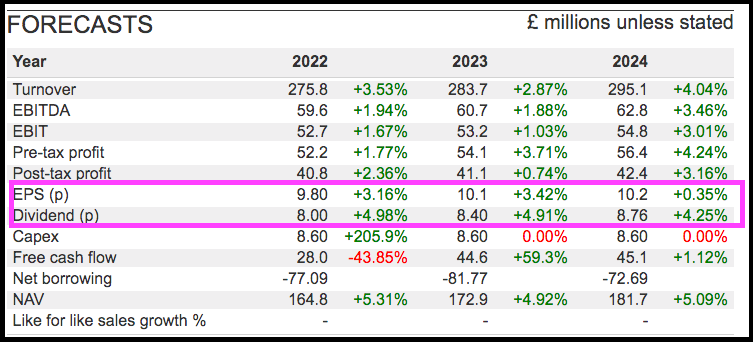

The subdued update has translated into modest growth projections for the next few years:

Note the small differences between the predictions for earnings per share (EPS) and dividend per share.

The 2021 payout was covered only 1.26 times and the projected cover for the 2024 payout drops to a rather thin 1.16 times. I do wonder whether part of that £83m cash hoard could/should be spent on new projects that one day will enhance profits and provide greater support for the dividend.

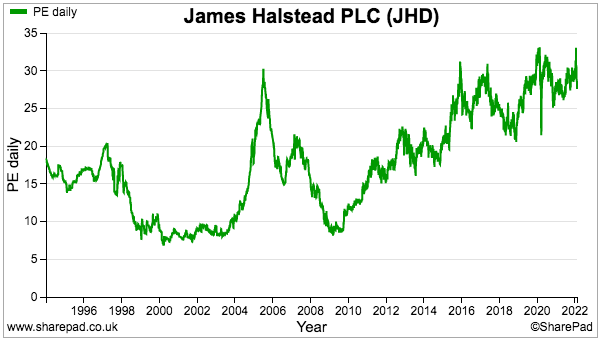

Although the share price has advanced only 9% during the last five years, the present valuation does not appear obviously cheap at approximately 27 times forecast earnings:

The rating is perhaps not surprising for what I would venture is a quality company selling a quality product. But whether all that quality makes Halstead a ‘safe haven’ from the current market is something only you can decide.

The share-price lesson over the last five years is that, even with a first-class operator such as Halstead, valuation eventually matters and returns may be limited if you pay a high multiple for earnings growth that subsequently slows.

Just ask anyone who bought Halstead at 25p during 1996. They had to wait eight years before they could claim a capital gain:

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Maynard writes about his portfolio at maynardpaton.com and hosts an investment discussion forum at quidisq.com. He does not own shares in James Halstead.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Strikes me that in an inflationary environment six months’ ‘worth’ of stock in the warehouse should enable the price of current production to rise proportionally without alienating customers. I hold.

Hi Maynard,

A cogent and well thought out piece. You are so persuasive that I am almost buying it.

Do you have a method whereby you can list these family led companies in some merit order where JHD comes below the line?

Congratulations on another analyst article. you lead us all by example.

Colin Farrier

Terrific report on wonderful company, Maynard. Bravo. Loved the video. James Halstead is drowning in cash (nice problem to have!) You put your finger on a few signs of strategic drift-cosiness of Board, no obvious sign of CEO/FD succession plan, is the balance sheet being applied to provide future growth?

Hi Colin and Chris,

Glad you both liked the article. SharePad allows you to screen for director holdings, from which you can order the shares in any way you like. See my Renishaw article for an example: https://knowledge.sharescope.co.uk/2019/04/08/screening-for-my-next-long-term-winner-renishaw/

Maynard

Great article. It woud be nice if the UK market had more high quality family owned companies like this.

Thanks Maynard, the comment from the annual report : “The board has discussed with the trustees the future accrual of benefits and the trustees made clear that an equitable payment by members would see an increase in member contributions of around 12-15%.”

To me this reads that scheme members (current employees) would be expected to pay more into the scheme if there was to be an equitable split between the company and the approximately £4m extra contributions being paid in, and the scheme members. That’s not to say it will happen but only what would be equitable, and that would of course represent a staff pay cut.

I like the review, very interesting, if Warren would call it a wonderful company, let’s wait for reasonable prices, say PE of 15.

Colin

Thanks Colin. Funnily enough I had cause to re-read this article the other week and came to the same conclusion as you (albeit far more slowly)!

Maynard

Hi Maynard

I’d always imagined that for most normal businesses ROCE is the better measure of the performance of the business itself. Can I ask – why did you look at the long term trend in ROE rather than ROCE?

Charles

Hi Charles

To be honest there is not much between ROCE and ROE, and there are so many nuances with their calculations that they can be largely academic anyway for many shares due to the business models employed, accounting protocols and other matters. I choose ROE over ROCE as that focuses on the returns generated by money shareholders have injected into the business, rather than on other forms of financing as well. Given I tend to look at cash-rich shares, using ROE versus ROCE ought not to matter a great deal. Assuming both ROE and ROCE are similar, then their trend over time is perhaps more important.

Maynard