ASOS share news Fashion website ASOS is among the market’s greatest growth stocks, but a recent update knocked 18% off the share price. The P/E may not be outrageous if huge warehouse and IT costs can one day deliver a suitable return.

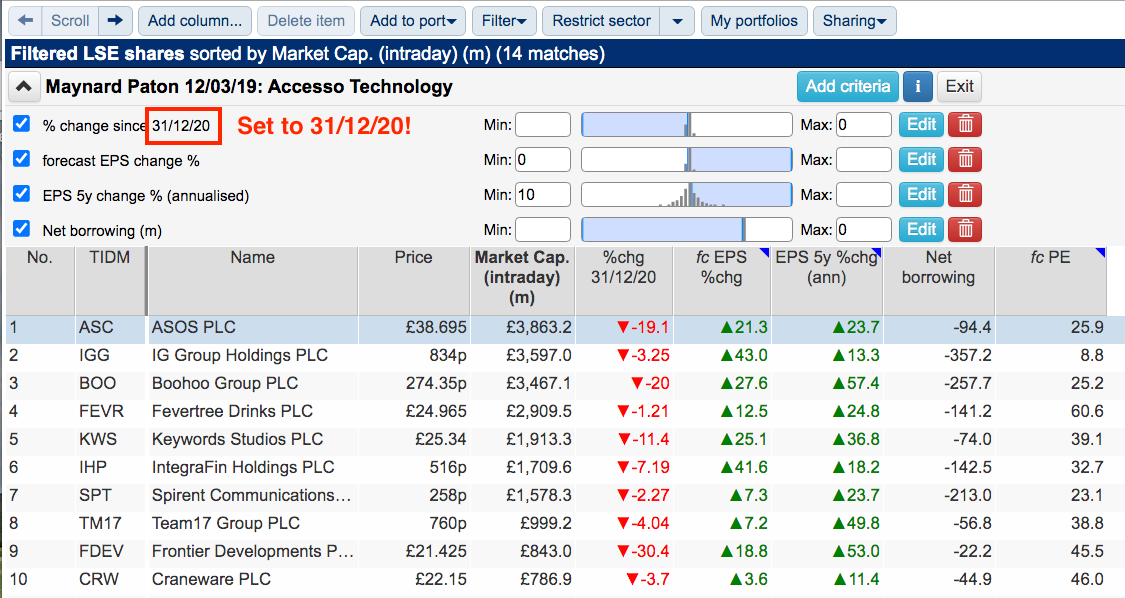

One of my favourite screening strategies is to hunt for attractive growth companies with unloved share prices.

The criteria I use for these searches are:

1) A negative share-price performance since the start of the year;

2) A compound 5-year earnings growth rate of 10% or more;

3) A forecast 1-year earnings growth rate of at least 0%, and;

4) Net borrowing of zero or less (i.e. a net cash position).

The other day the filters returned only 14 matches…

…of which five — IG Group, Boohoo, Fever-Tree Drinks, Frontier Developments and Craneware — I have already evaluated for SharePad.

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 12/03/19: Accesso Technology” filter within SharePad’s amazing Filter Library. My instructions show you how. Make sure to set the ‘% change’ date to 31/12/20!)

I selected ASOS from the remaining nine names because the company:

* Had the largest market cap on the list;

* Boasts an incredible growth story, and;

* Recently issued a trading statement that wiped 18% off the share price.

Let’s take a closer look.

The history of ASOS

“We read a stat back in 1999 that when the programme Friends aired, NBC got 4,000 calls about some standard lamp in one of their apartments asking where it could be purchased. So that was the real idea behind the business”.

So recounted Nick Robertson within the book How They Started: Digital about why he established ASOS during 2000. “Anything that gets exposure in a film or TV programme creates desire among the public, so we based the shop around that.”

Initially called AsSeenOnScreen.com and selling everything from stuffed toys to kitchen equipment, the ASOS website soon became dedicated to fashion and “affordable star style” for 16-24 year olds.

Prompting the fashion strategy was one of Mr Robertson’s first employees, a product buyer from Sir Philip Green’s Arcadia. Her industry expertise simply led to much better sales margins from clothing than stuffed toys.

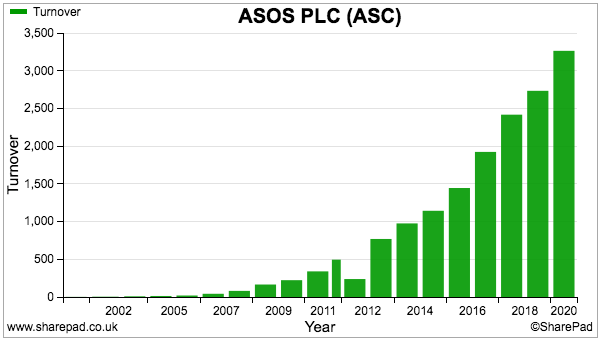

Early losses had turned to profit by 2004, which supported Mr Robertson’s ambition for ASOS to one day become the “UK’s premier online fashion retailer“. Revenue at the time was just £13 million.

Fast forward to 2021 and, buoyed by the wider transition to online shopping, sales now top £3 billion:

The launch of numerous overseas websites, some savvy marketing and a product range that has expanded from 500 lines to 85,000 have also helped drive the meteoric growth.

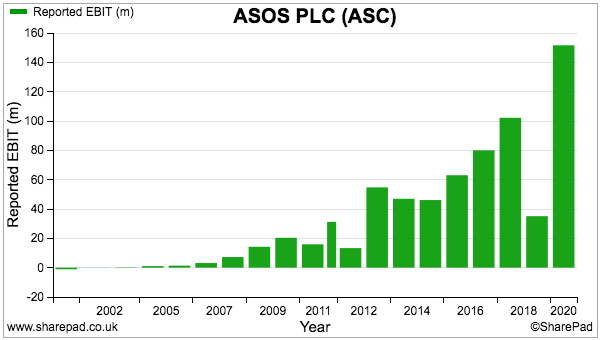

Profit has trended higher, too, albeit not without setbacks:

The 2019 performance was hindered by runaway costs associated with reorganising warehouses in Europe and the States, which had the knock-on effect of dampening sales in those regions.

Costs associated with revamping UK warehouses have also influenced reported profit. ASOS has been particularly unlucky with its domestic depots, with both its Barnsley site (2014) and a former Hemel Hempstead site (2005) catching fire and causing a suspension of website orders.

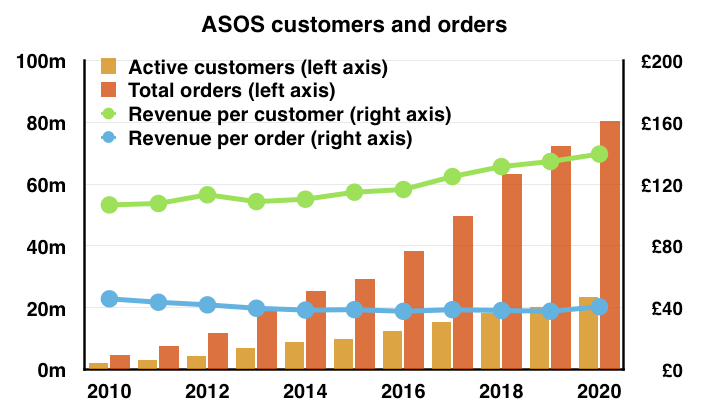

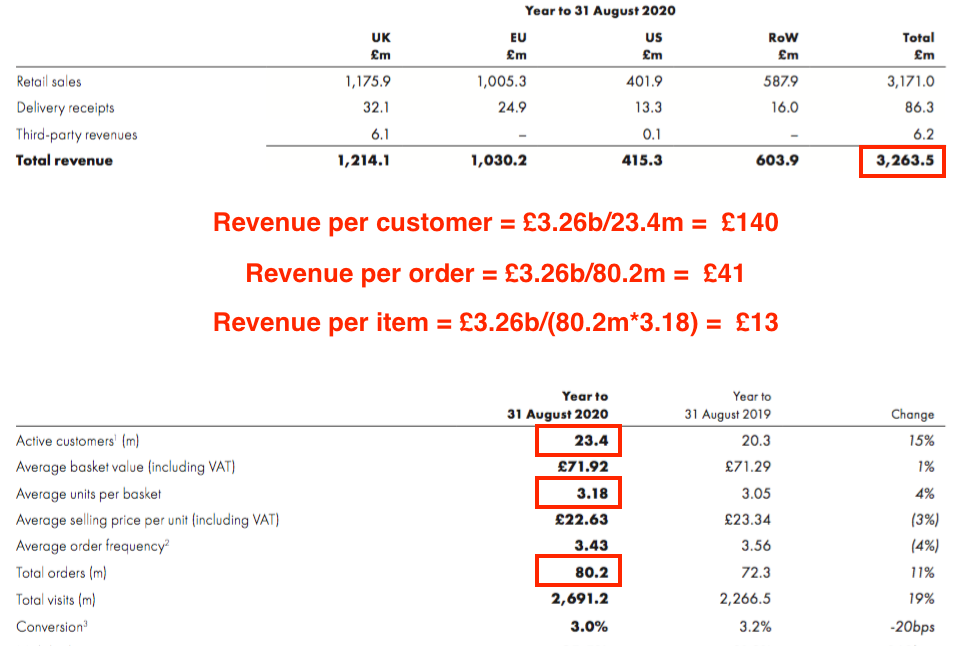

Active customers now total more than 23 million and last year submitted 80 million orders.

Although revenue generated from the typical order remains around £40, revenue per active customer has commendably improved over time to approximately £140 due to customers increasing their orders from 2.3 times to 3.4 times a year:

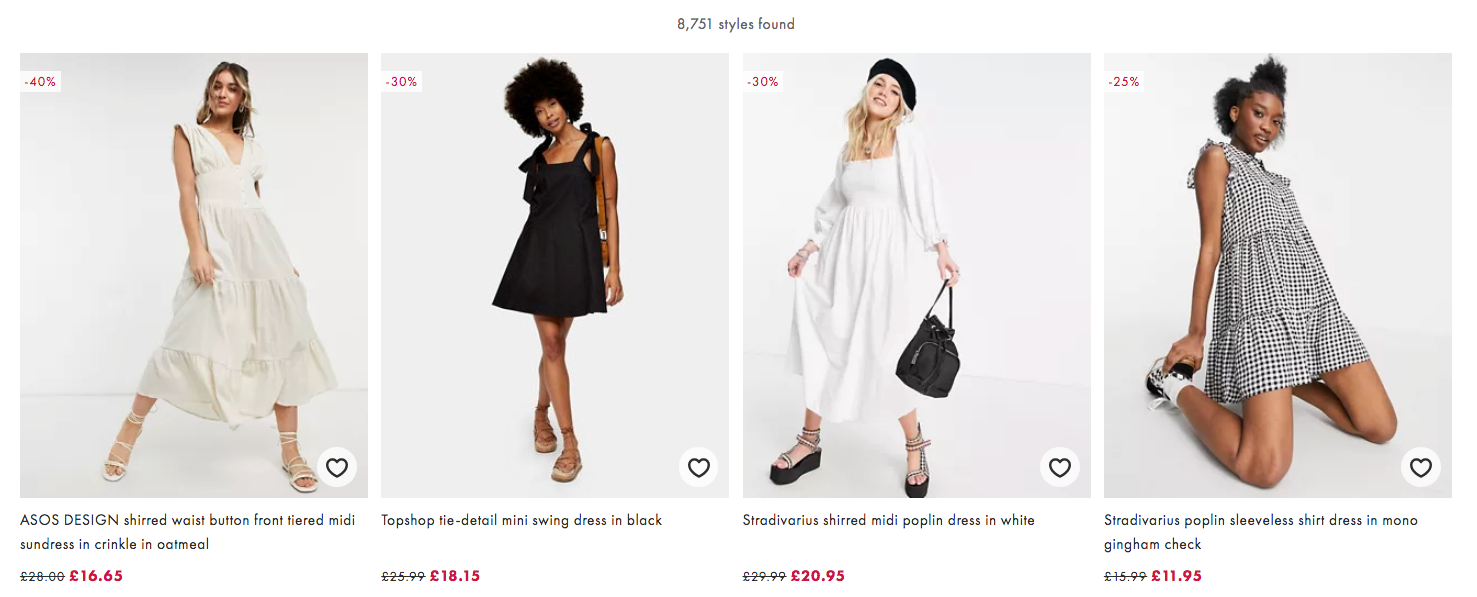

Just so you know, top items within the company’s current sale include a Topshop tie-detail mini swing dress in black for £17 and a Stradivarius poplin sleeveless shirt dress in mono gingham check for £12. Pay £10 to become an ASOS Premier customer and you also enjoy free next-day delivery for a year:

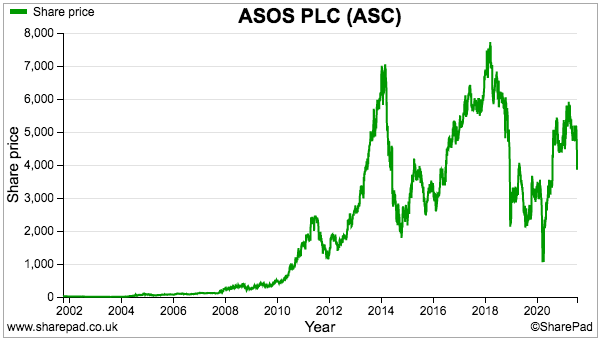

The shares have achieved almost legendary status among UK mega-baggers:

After joining AIM during 2001 at 20p, the price bottomed at 3p in the 2003 dot-com crash only then to peak at £77 during 2018. Anyone lucky enough to get in at the low has enjoyed up to a 2,566-fold return.

Periodic worries about growth rates and rising costs have since created significant share-price swings, and left the recent £39 price supporting a £3.9 billion market cap.

ASOS shareholders who have already multi-bagged their investment will probably not mind the absence of a dividend since the float.

SharePad summary of ASOS stock

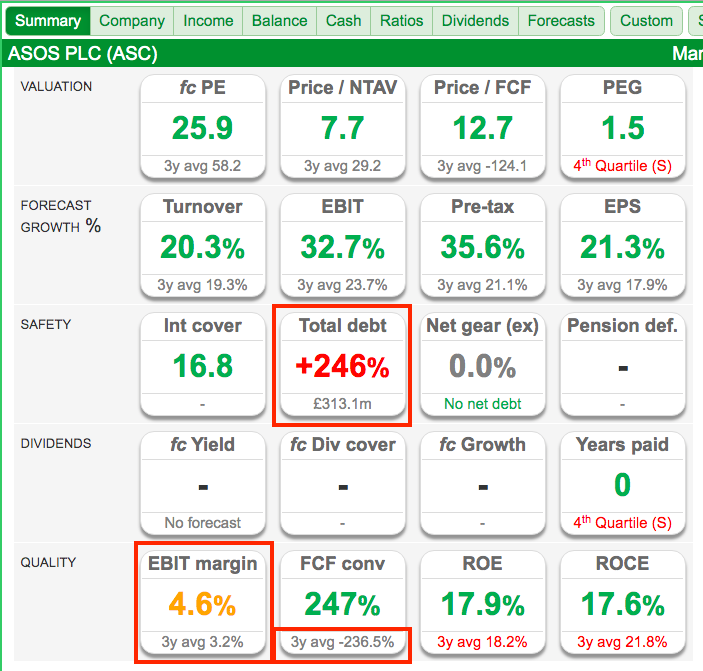

The SharePad summary for ASOS is shown below:

Points of interest include:

* An operating margin of only 4.6%;

* Free cash flow conversion averaging a negative 237% over three years, and;

* A significant increase to the level of debt.

Let’s begin with the operating margin.

ASOS stock control and Operating margin

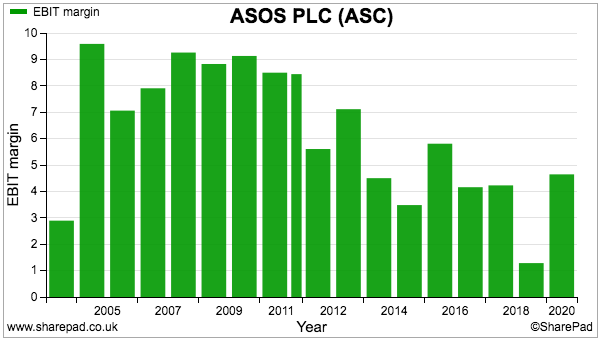

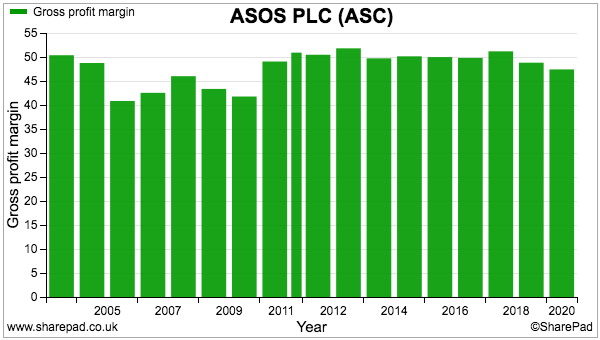

ASOS has generally operated with a 4%-5% margin for the last ten years:

Although a mid-single-digit margin is not traditionally associated with superb competitive ‘moats’, ASOS clearly has something special about it to have delivered that aforementioned growth record.

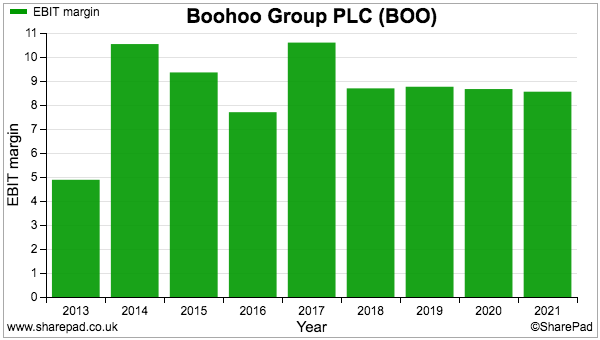

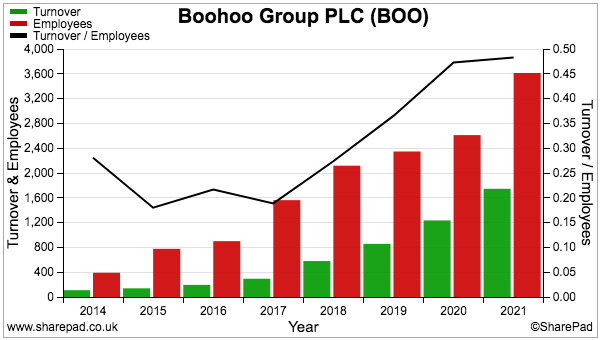

The obvious comparison to make is with rival fashion website Boohoo, which has operating margins regularly topping 8%:

The margin difference with ASOS is due mostly to stock.

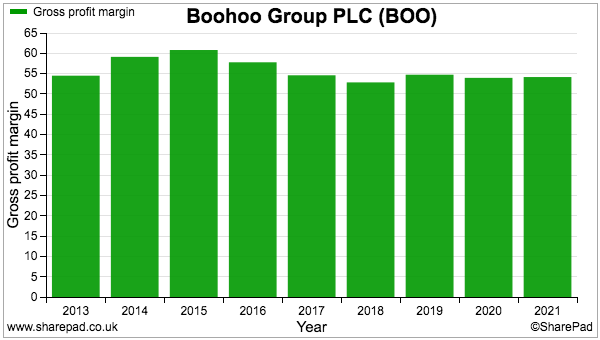

Boohoo’s gross margin is 54%, which means the retailer can buy stock for £46 and sell it on for £100:

In comparison, the gross margin at ASOS was 47% last year and has rarely topped 50%, indicating ASOS must buy stock of at least £50 to sell it on for the same £100:

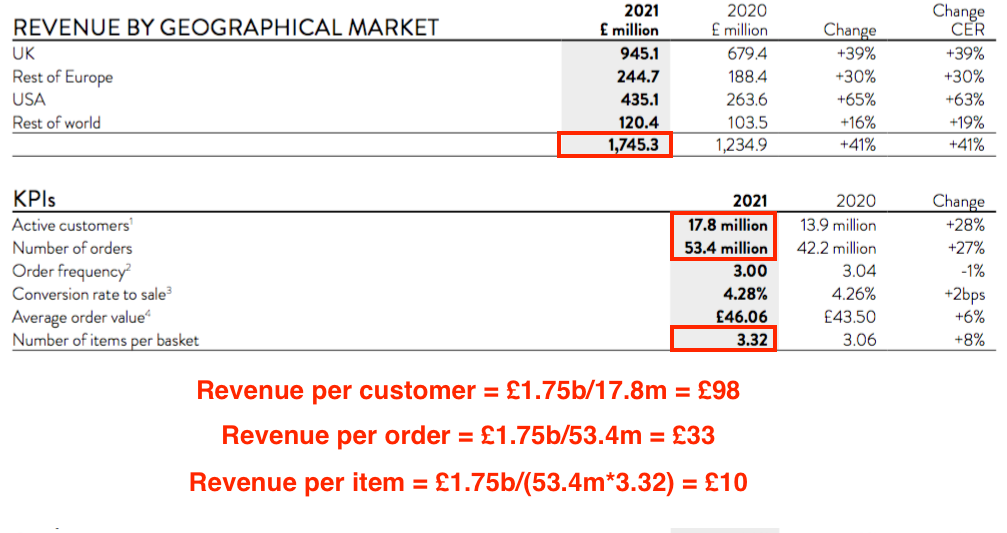

Digging deeper, last year Boohoo’s 17.8 million customers made 53.4 million orders comprising 176.2 million items to generate revenue of £1.75 billion:

Boohoo’s revenue per customer was therefore £98, with revenue per order at £33 and revenue per item at £10.

The same stats for ASOS were £140, £41 and £13 — all approximately 30% up on Boohoo:

I am not quite sure why Boohoo with its:

* Lower spend per customer;

* Lower spend per order, and;

* Lower item pricing…

…can earn a higher gross margin than ASOS. I would have thought ASOS’s higher-priced clothes would have earned the greater mark-up. Perhaps Boohoo sells a lot of own-brand items that capture more profit.

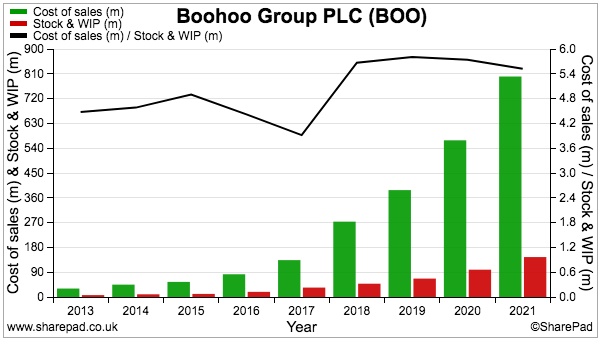

Not only can Boohoo generate a better margin on its stock, the rival enjoys better stock control.

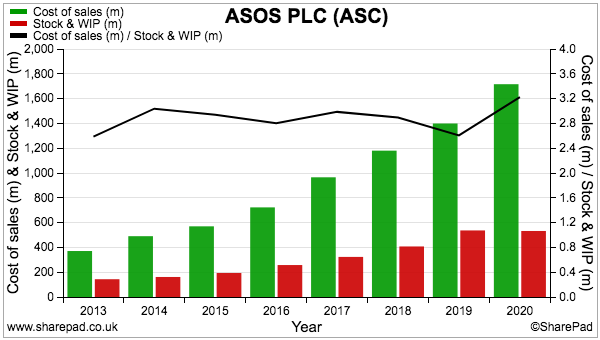

The chart below divides Boohoo’s cost of sales by its stock level to derive ‘stock turn’ (black line, right axis) — a broad measure indicating how long items may sit in the warehouse before being sold:

Boohoo’s stock turn of around 5x implies items sit in a warehouse for an average of 2.4 months (12 months divided by 5) before being sold.

In contrast, stock turn at ASOS is about 3x, which implies its clothes sit in a warehouse for four months before being sold:

I estimate ASOS could release cash of approximately £200 million — equivalent to £2 per share — from stock were it to match Boohoo’s level of stock management.

Free cash flow and capital expenditure

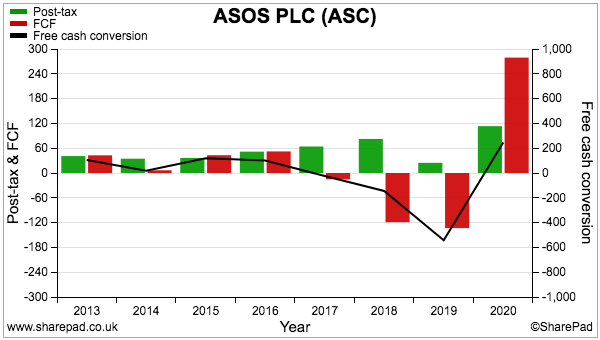

ASOS’s cash-conversion percentage (black line, right axis) has not been very consistent:

My Renishaw write-up explained how cash conversion is typically held back by:

* Additional working capital absorbing significant amounts of cash, and/or;

* Expenditure on tangible and intangible assets substantially exceeding the associated depreciation and amortisation charged against profit.

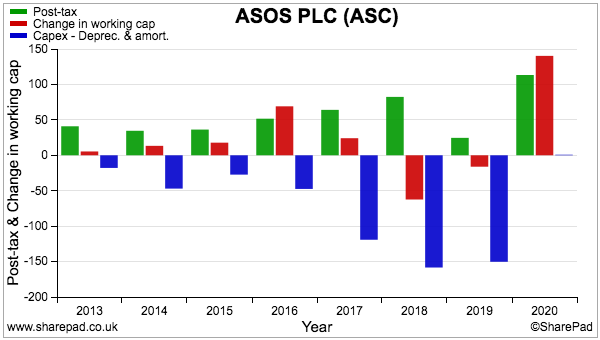

The following chart compares ASOS’s earnings (green bars) to additional investment in working capital (red bars) and the ‘excess’ capital expenditure (blue bars):

The ‘excess’ capital expenditure certainly requires investigating.

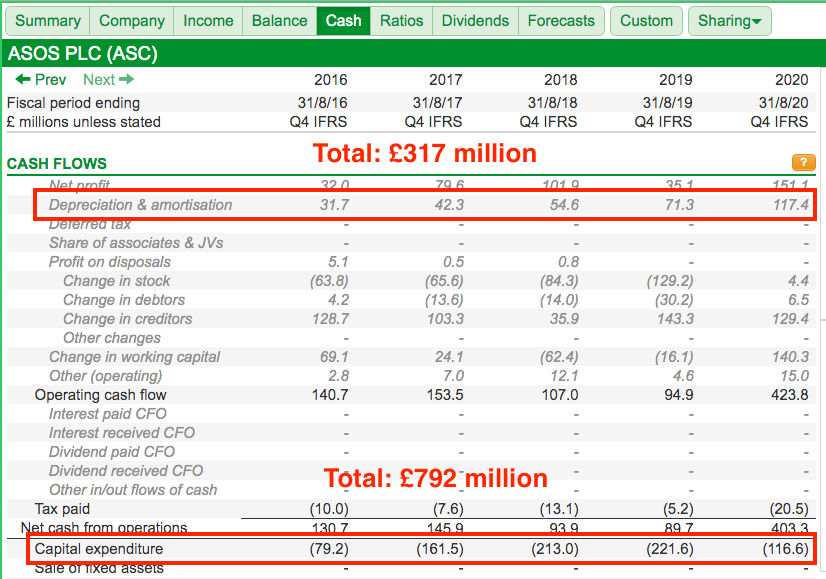

SharePad’s Cash tab shows an aggregate £317 million charged against profits as depreciation and amortisation during the last five years:

Capital expenditure has meanwhile absorbed total cash of £792 million.

The £475 million difference is extremely significant given the aggregate operating profit during the same five years came to £431 million.

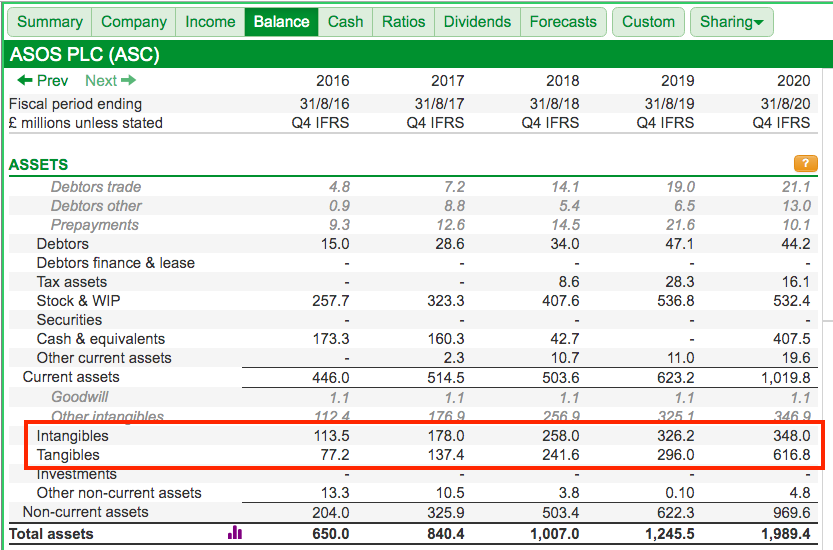

The balance sheet shows rising levels of both tangible and intangible items, which tells us where the £792 million was spent:

The annual report is needed to discover what exactly is going on.

Capital expenditure and software development

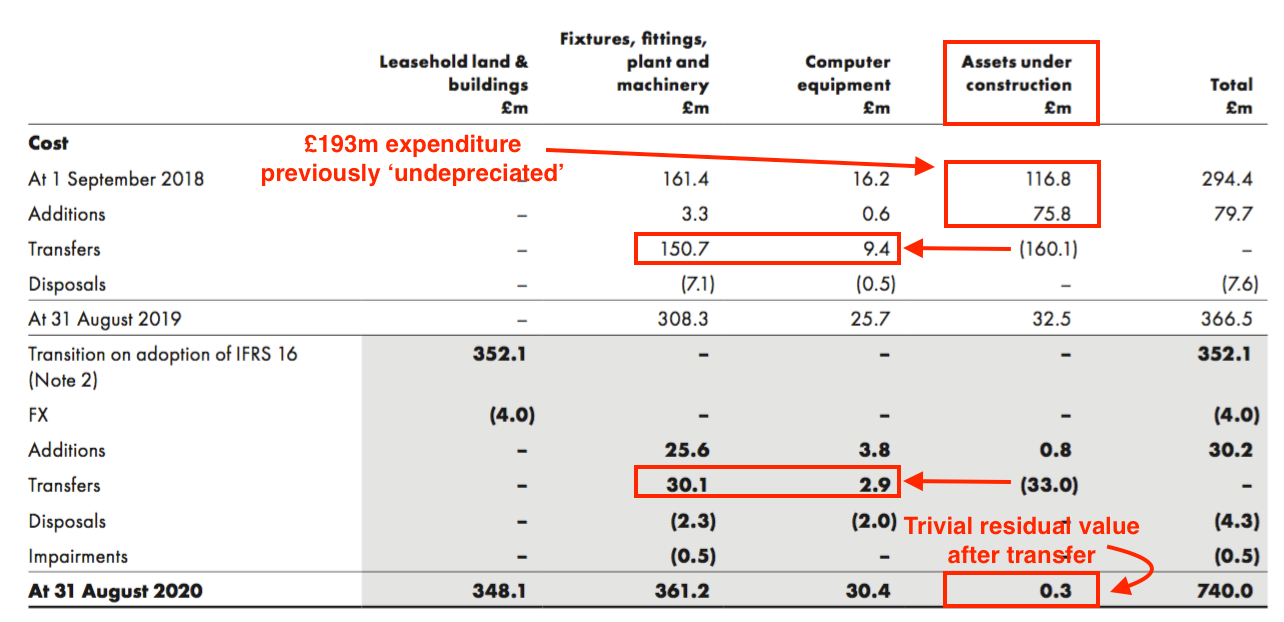

The note below shows ASOS having spent approximately £193 million on tangible “assets under construction” (i.e. new warehouses):

Such expenditure has now all been reclassified as fixtures, fittings and other equipment, and will soon incur a depreciation charge in the normal way.

The accounting therefore does not seem unreasonable at present…

…especially when ASOS claims this construction expenditure will expand sales capacity from £4 billion at present to more than £6 billion during the next two years.

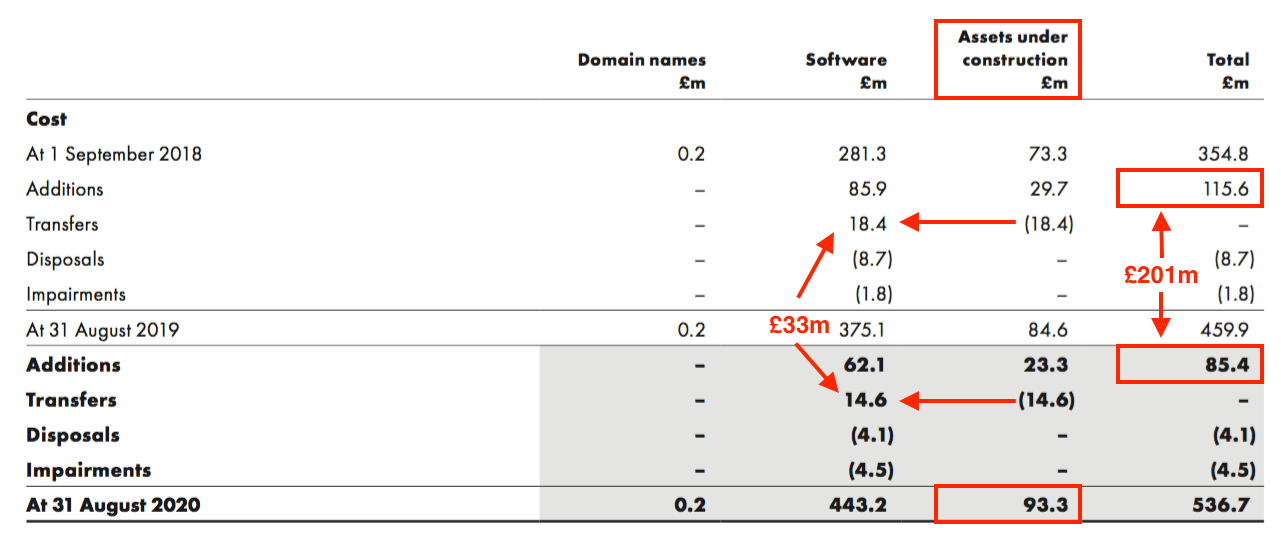

I am not so sure about ASOS’s intangible expenditure though.

“Assets under construction” here represent a comprehensive internal computer system that has recently replaced much of the group’s outdated software:

The accounts show £33 million of these intangible “assets under construction” transferred to “software“, with £93 million remaining.

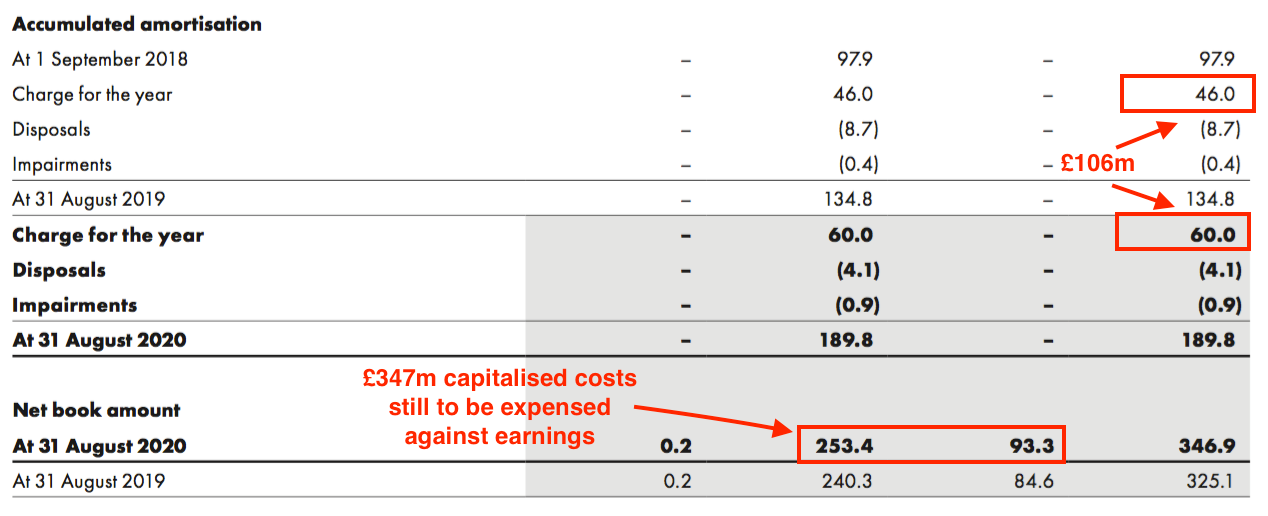

The accounts also show a total of £201 million spent on all software during 2019 and 2020, and an associated amortisation charge expensed against earnings of only £106 million:

The aggregate difference between all the cash spent on developing IT systems and what has been charged against profits is represented by the £347 million combined net book values of the software.

The upshot is this £347 million will at some point have to pass through the income statement. For perspective, total reported earnings during the last five years were £309 million…

… and would have been just £36 million had all the software costs been expensed as incurred.

Whether internal software development should be viewed as a long-lived asset and the costs capitalised onto the balance sheet is debatable.

After all, IT projects could be viewed as a normal cost of business and expensed as such. A capitalisation policy may also flatter reported earnings and influence calculations for profit-based bonuses.

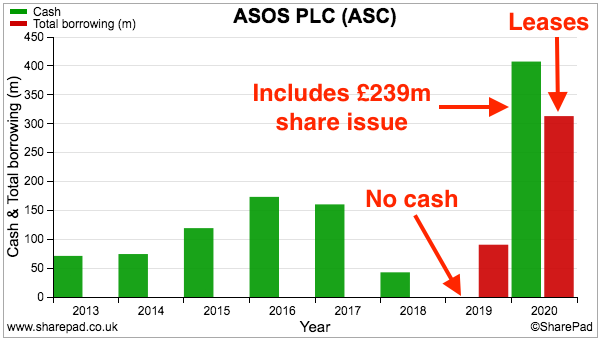

What is not up for debate is the effect on ASOS’s cash following all the expenditure. The bank balance (green bars) went from £173 million to zero between 2016 and 2019:

The lack of cash created a problem when the pandemic emerged a year later, with ASOS deciding to raise £239 million by issuing 19% more shares at £16. The timing was not great; the share price first attained £16 nine years earlier during 2011.

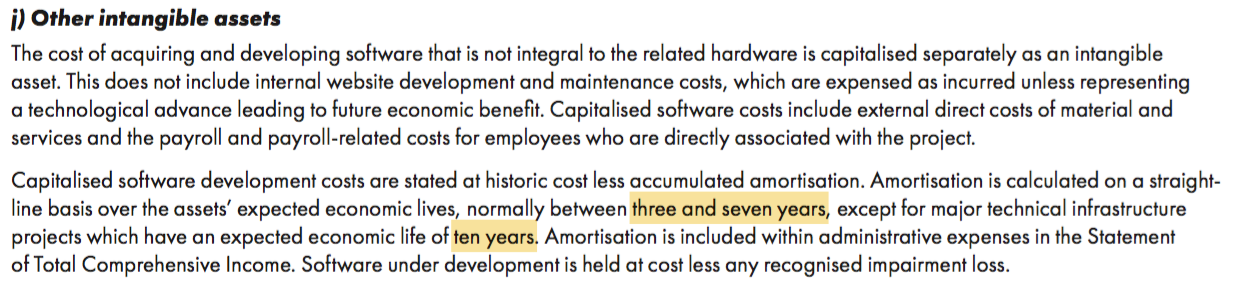

Shareholders can only hope the software expense will be worth it. ASOS reckons the new system’s useful life could be up to ten years, which is a long time for an IT project not to be overhauled:

Note that the sudden advance to borrowings during 2020 in the earlier chart was due entirely to IFRS 16 and the new treatment of operating leases as a financial obligation.

However, ASOS does now carry debt through a recent £500 million convertible bond. If converted, this bond will dilute shareholders by 6% and, alongside that £239 million share placing, is another of today’s realities that has resulted from the substantial capex to create tomorrow’s growth.

Employees and management

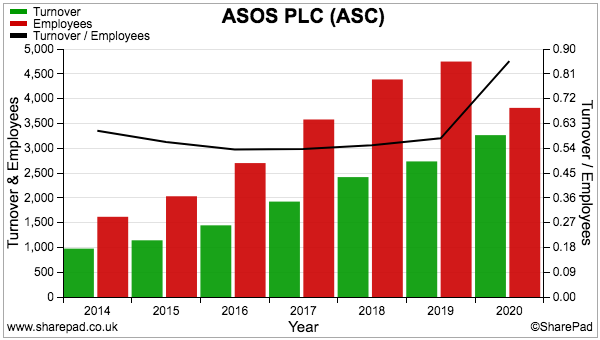

You never know, maybe all the IT expenditure will be worth it. Staff productivity as measured by revenue per employee has recently shown encouraging progress:

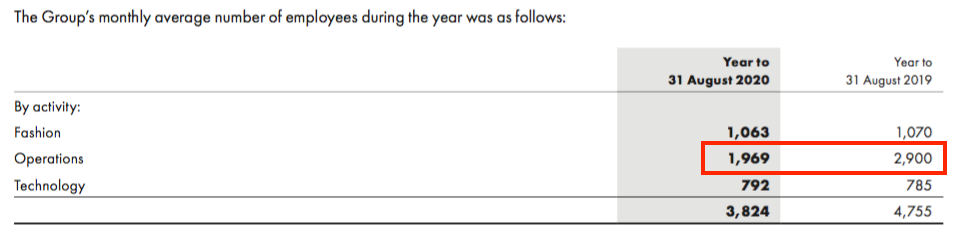

Last year ASOS managed to improve sales by 19% despite reducing the workforce by 20%.

I don’t know whether this performance was a one-off due to the pandemic or is the start of a much more efficient operation. But 931 workers left Operations…

…which might indicate all the warehouse and software investment is starting to bear fruit.

Note, too, that ASOS’s revenue per employee of £800k-plus exceeds the near-£500k at Boohoo:

Perhaps one day ASOS’s IT systems could also improve margins and stock management to match the levels at Boohoo.

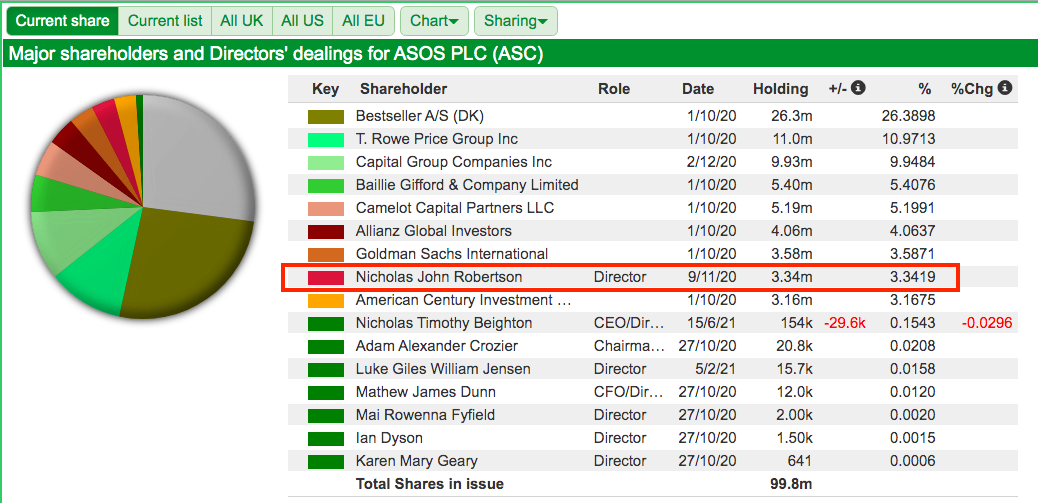

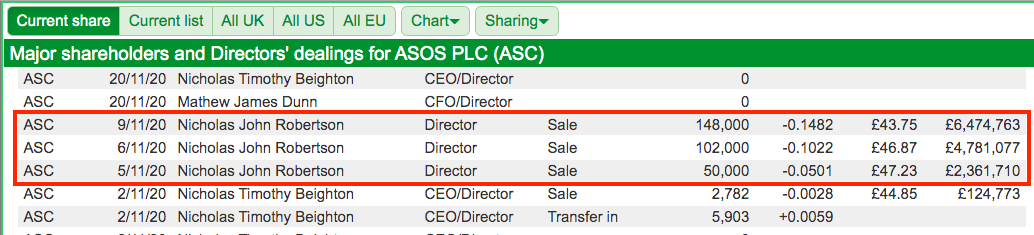

The aforementioned Nick Robertson was not among the 931 to leave ASOS last year. He remains a non-exec after stepping down as chief executive during 2015.

Mr Robertson retains a 3%/£127 million shareholding and should still possess the ‘owner’s eye’…:

…although SharePad indicates his share sales have raised approximately £250 million since 2010:

Running ASOS today is Nick Beighton, who joined ASOS as finance director during 2009 and has also worked as the group’s chief operating officer. As successors for entrepreneurial founders go, the long-tenured Mr Beighton seems as good a replacement as any.

Forecasts, valuation and should you buy ASOS shares?

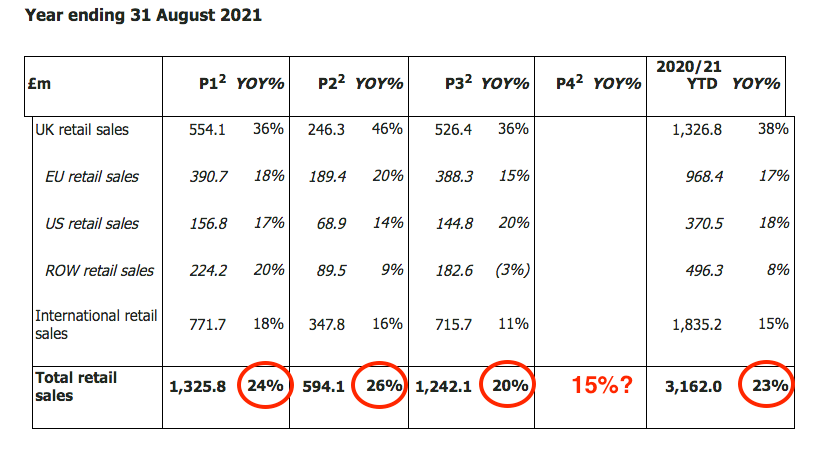

A trading statement issued the other week knocked 18% from ASOS’s share price. The following text caused the wobble:

“Trading in the last three weeks of the period was more muted, as continued COVID uncertainty and inclement weather, particularly in the UK, impacted market demand. We anticipate a measure of volatility to continue in the near term, given the rapidly evolving COVID situation worldwide.

As a result, we expect our underlying P4 growth rate to be broadly in line with the prior year comparable period.”

Last year’s underlying P4 growth rate was 15%, which if repeated for the current year would be notably below the 20%-plus growth rates achieved year to date:

P4 refers to period 4 and covers only July and August, which does beg the question whether two months of sales figures should make an 18% difference to the share price. I would venture broker forecasts for the next few years to be of far more significance.

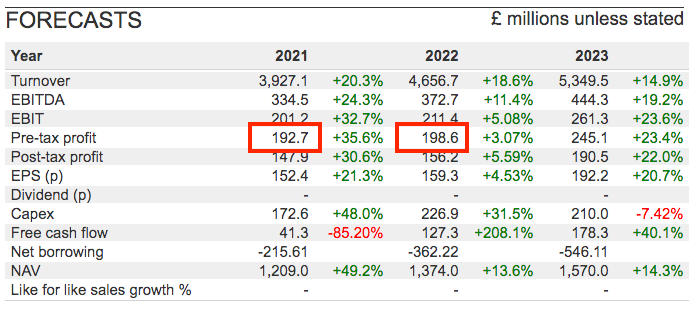

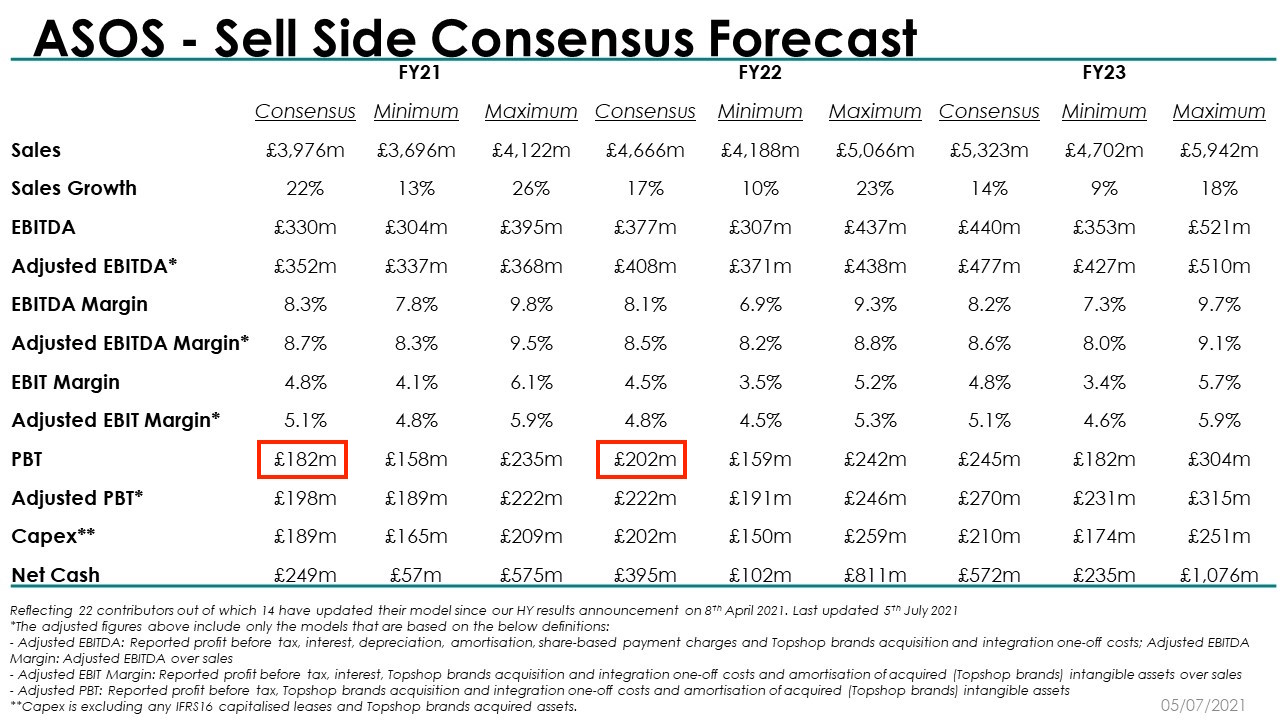

ASOS’s trailing twelve-month pre-tax profit stands at £218 million, which exceeds the estimates shown on SharePad and ASOS’s website for both 2021 and 2022:

True, interim results issued during April showed profit was enhanced by various pandemic-related cost savings of £49 million — and such benefits may not be sustained if Covid ever subsides. But even so, the near-term profit projections do appear very achievable.

Indeed, the P/E based on the 2023 estimates is approximately 20, which does not feel completely outrageous given ASOS’s growth record and the prospect perhaps of 15% annualised sales growth during the next few years.

But remember: ASOS’s earnings have never really translated into cash following the substantial warehouse and software expenditure. The danger is that ASOS must keep the capex taps running even if sales growth stalls… and the business is unmasked as a genuine money pit.

Mind you, if the new warehouses and IT do eventually deliver a generous cash payback, this mega-bagger journey should not end at the recent £39. So far at least, assuming the cash expenditure will pay off has generally worked out well for shareholders.

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Maynard writes about his portfolio at maynardpaton.com and hosts an investment discussion forum at quidisq.com. He does not own shares in ASOS.

Where do you land in the camp of ASOS vs Boohoo? We’d love to hear from you in the comments section below

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Hi Maynard,

This is an Elephant now and they don’t gallop.

Please take a look at SOSANDER.

Cheers

Nigel

Hello Maynard

Your analysis is truly impressive. You give the stocks the full car wash treatment!

My question is this. Why have you not mentioned the glaring drops in broker forecasts for pbt and eps?

FY22 eps growth forecast is a puny 4.53% compared to 21.3% for previous year.

Similarly pbt drops to 3% versus 35.6%.

These are massive downward changes and you cannot describe it as a growth stock.

What am I missing?

Thanks.

Hi Nigel

This elephant may still be jogging though, and they can crush ants such as Sosander 🙂 Might take a look at Sosander in the future.

Maynard

Maynard,

You asked the question, “Should you buy ASOS shares?”

Well this beast has a market cap of £3790m, but it has never payed a dividend since it was founded 20 years ago. Who in their right mind would therefore buy shares in an outfit with this market cap, when it appears there is almost zero chance of even a dividend? How many other companies can you find on Share Pad of such similar market cap that have not payed a dividend for over 20 years? Is this the only one?

On top of that I notice that at the start of 2014, the share price was at £70, which is nearly twice what it is today.

So the answer is a big fat NO!

Cheers

Nigel

Hi Nigel,

I can only surmise ASOS is going for an Amazon-type expansion, whereby large sums are invested today in the hope of enjoying huge scale tomorrow — with no dividends being declared along the way.

I doubt there are any other £3.9b companies that have not paid a dividend for 20 years, but I also doubt there are any other £3.9b companies that have 100-plus bagged during the same time. Veteran ASOS shareholders could argue reinvesting cash flow and not paying a dividend has been the right decision, at least to date.

With hindsight we can see buying at £70 was a bad idea, but since then the price has fallen and earnings have risen, so now may be a better buying opportunity.

But that is something for each individual to decide.

Maynard

Hi ram,

Car-wash treatment 🙂

Slowing profit growth for 2022 due to Covid ‘windfall’ for 2021 –> “True, interim results issued during April showed profit was enhanced by various pandemic-related cost savings of £49 million — and such benefits may not be sustained if Covid ever subsides.”

Forecasts for 2022 do not expect a repeat Covid windfall. But then back to decent profit growth forecast for 2023. Sales growth estimates meanwhile are very reasonable at c15%-plus per annum.

Maynard

ASOS brings back mixed emotions for me. I think I was one of the first bloggers/writers to publish anything outside a broker note way back in cMay 2010 on the back of my logic the improvement in internet speeds could prove great news for online retailers. Back then I had a modest £2200 investment at 7.20p. I felt quite smug banking 100% plus within 5-months, and used those funds to buy Cyprotex, which did OK as well. The remainder of the initial investment in ASOS was allowed to ride to with an every narrowing trailing SL, filled at 330p. Again, I was feeling quite smug. I wasn’t feeling so smug thereafter. I never bought back in. I have significant regret.

Could be worse. I have heard tales from certain prominent PIs buying at 3p and selling at 9p.

Buying at £46 and selling at £100 (your figures for Boohoo) looks to me like a gross margin of almost 112%, not 54%. If ASOS have a gross margin of 47% surely they buy at £100 and sell at £147?

Hi Alan,

If you buy clothes for £46 and sell them for £100, your gross profit will be £54. Gross margin is gross profit expressed as a percentage of sales, which will be 54/100 = 54%

Maynard

Hi Maynard

Good article as always.

ASOS will always struggle to match Boohoo for stock turn. The reason being is ASOS sells a lot of brands that are forward order for the season and this requires the buyers to guess the market demand in advance. Boohoo are much more trial and error, they make much more in season if they try something and it works they will make lots more of it. ASOS will have winners and losers with the losers having a stock holding. Boohoo will have the same winners and losers but will have only manufactured/ordered very small qualities of the losers.

Brands which ASOS stocks have a lot less flexibility in the ordering process and lead times than the Boohoo model.

Hope this helps explain some of the stock holding issues.

Dave

Thanks Dave, that all makes perfect sense.

Maynard

Hi Maynard

you ask “Where do you land in the camp of ASOS vs Boohoo? We’d love to hear from you in the comments section below”

Actually, there is a higher order question which makes all comparisons of Boohoo vs Asos academic and waste of time. Given the persistent allegations of misconduct and fraud and now a US court case, would you as an investor buy BOO shares?

As an investor, no. As a gambler, go ahead. The odds are clearly better than winning the lottery.

All the best.

As I understand it, the misconduct relates to a historic failure by BOO to control its supply chain, something which it is working hard to put right. The “fraud” and US court case seems to relate to claiming goods have been discounted when they had not been for sale long enough at the non-discounted price according to US standards (but possibly not British ones). There are concerns about fast fashion in general – the generation of micro-plastics every time polyester is washed; the volume of water used in large-scale cotton production; the environmental impact of global transport to name a few. The governance of BOO is also an issue – the founders dominate the company but they have set a price target of 600p in a couple of years time or so. If the share price reaches that they’ll be in for a £millions payout so they have every incentive to put things right and restore confidence in the company.

Thanks for another excellent forensic investigation Maynard.

You are correct in drawing attention to the 10 year period associated with “major technical infrastructure projects”. This could cover a multitude of sins. Network cabling for example should last more than 10 years (generally warrantied for 25 years but typically a small percentage of the whole). Robotics used in picking etc – seems possible that might last ten years. Everything else, networking hardware, operating software, application software, I would suggest would generally need refreshing every 3 to 5 years. A “major technical infrastructure project” would typically contain elements of all of the above…..