Cash flow movements can often indicate whether or not a business enjoys a powerful operational advantage.

A strong business might:

- Receive customer payments upfront for goods/services it has yet to deliver, and/or;

- Pay suppliers months after goods/services have been received.

However, a weak business might:

- Receive customer payments months after its goods/services have been delivered, and/or;

- Pay suppliers upfront for goods/services it has yet to receive.Craneware and Greggs are examples of businesses with such favourable ‘working capital’ characteristics. Customers of Craneware pay their software fees in advance, while Greggs pays its suppliers long after its customers have bought their sausage rolls.

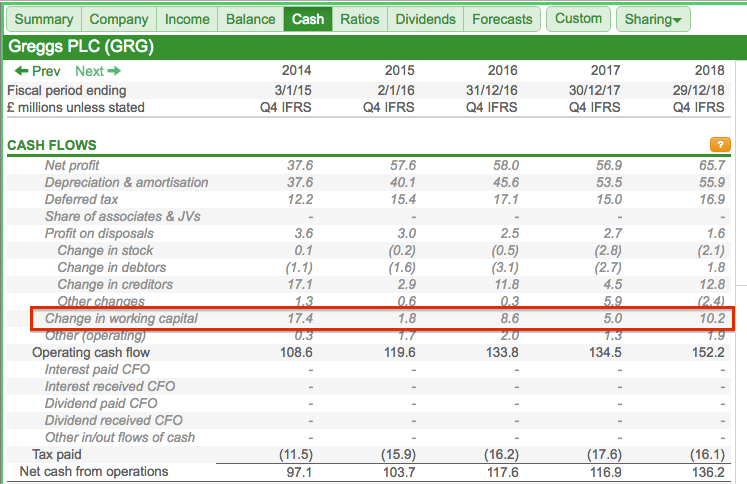

SharePad allows us to easily pinpoint companies with beneficial working-capital movements. We can find the relevant accounting information on the Cash tab:

We are looking ideally for companies showing positive numbers within the change in working capital line.

Filter

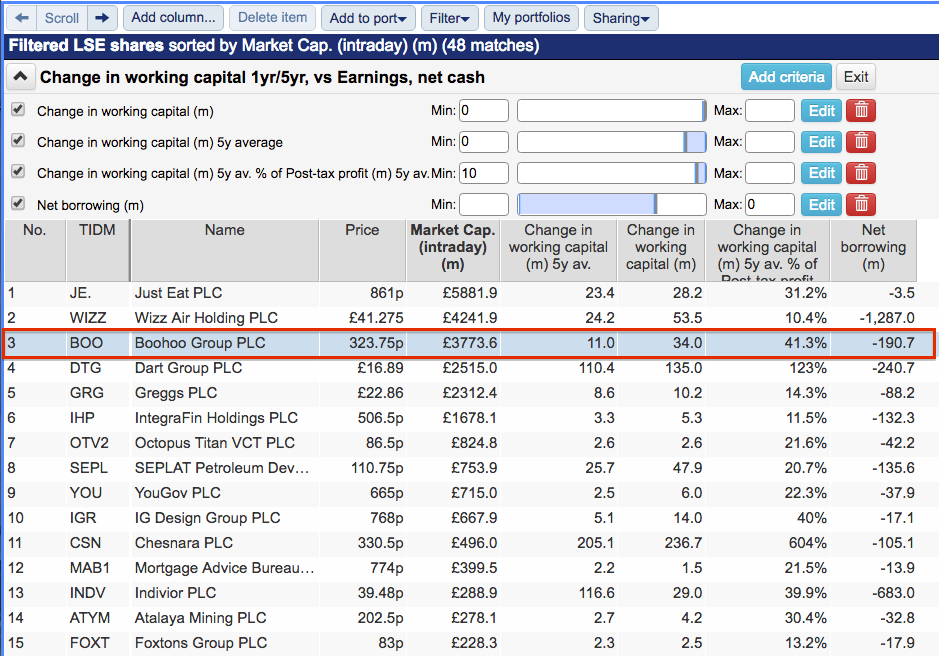

I created the following SharePad filter to track down companies with very favourable working-capital movements.

The exact criteria I used were:

- A positive working-capital cash movement during the latest year;

- Positive working-capital cash movements on average during the last five years;

- Total working-capital cash movements from the last five years representing 10% or more of total earnings, and;

- Net borrowings of less than zero (i.e. a net cash position).

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 12/02/20: Boohoo” filter within SharePad’s brilliant Filter Library. My instructions show you how.)

SharePad gave me 48 shares, from which I selected Boohoo, the prominent online fashion retailer.

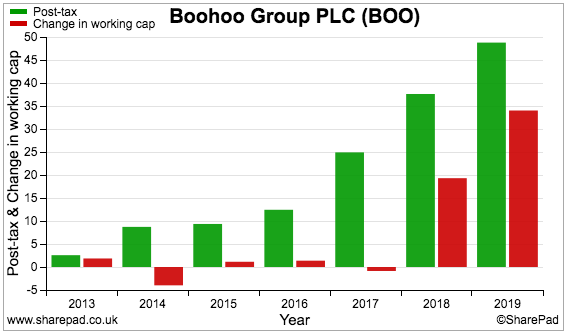

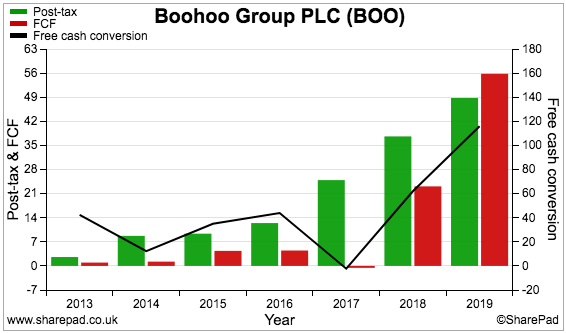

The chart below compares Boohoo’s earnings to its working-capital cash movements (red bars):

The last two years have clearly witnessed some very advantageous cash generation.

Let’s take a closer look at the company.

The business of Boohoo

Boohoo effectively began during the early 1990s when Mahmud Kamani employed Carol Kane as a designer for his family’s clothing business.

Mr Kamani and Ms Kane arguably devised ‘fast fashion’ in the UK. They offered the likes of Topshop and H&M six-week turnarounds from design to delivery at a time when other clothing suppliers took several months.

By 2006, the popularity of low-cost Primark had prompted the pair to build the original Boohoo website for (apparently) £1,500 and start selling clothes online.

Focusing on clothing for 18-30 year-old women alongside:

- Very low pricing;

- Limited-run ‘exclusive’ ranges, and;

- Relentless social-media promotion…

…then combined to create an extraordinary retail growth story.

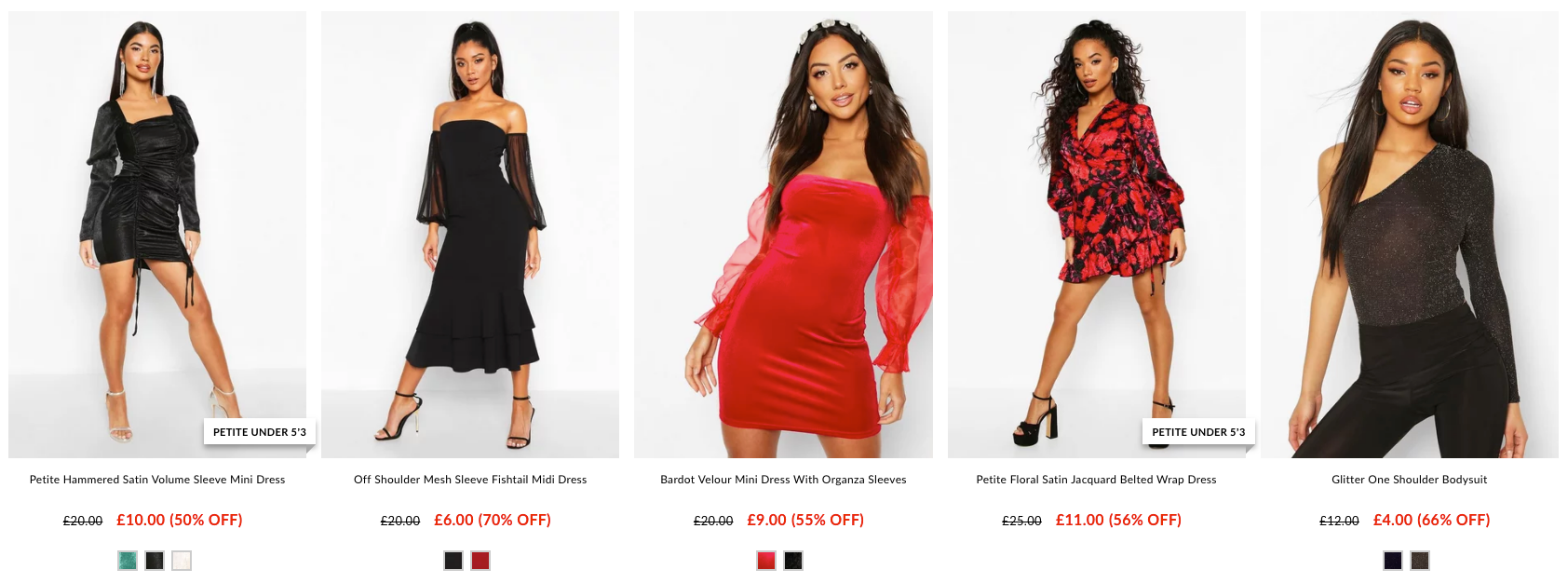

The Boohoo website now carries tens of thousands of different product lines, with hundreds replaced daily.

Top items within the company’s latest sale included a petite hammered satin volume sleeve mini dress for £10, an off-shoulder mesh sleeve fishtail midi dress for £6 and a glitter one-shoulder bodysuit for £4. Pay £10 to become a Boohoo Premier customer and you also enjoy free next-day delivery for a year.

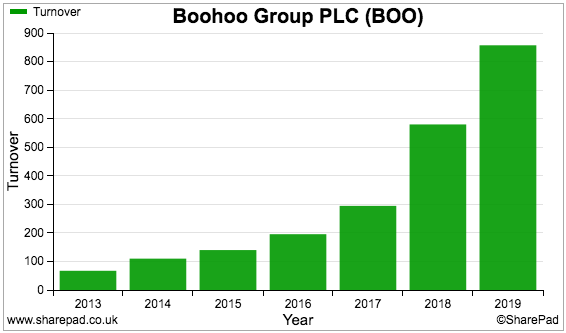

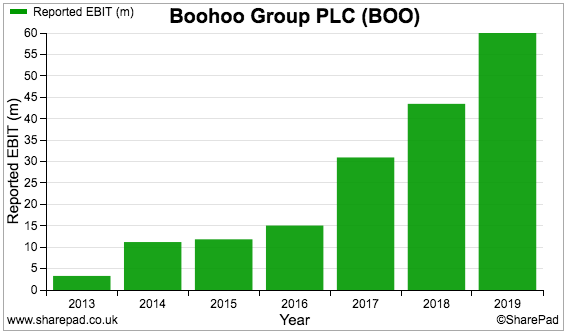

Boohoo floated during 2014, at which point sales were £110 million and operating profit was £10 million. The current year is expected to see revenue top £1.2 billion and profit come close to £100 million.

Launching a mens clothing range, opening numerous overseas websites and purchasing PrettyLittleThing and NastyGal all helped to underpin the robust progress.

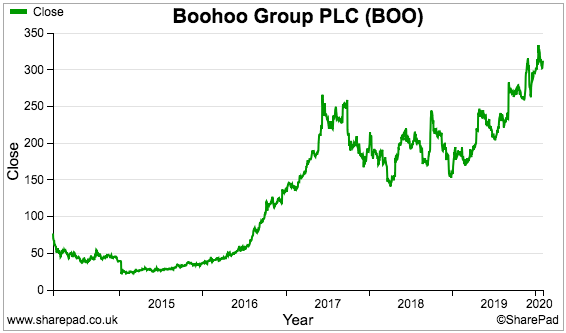

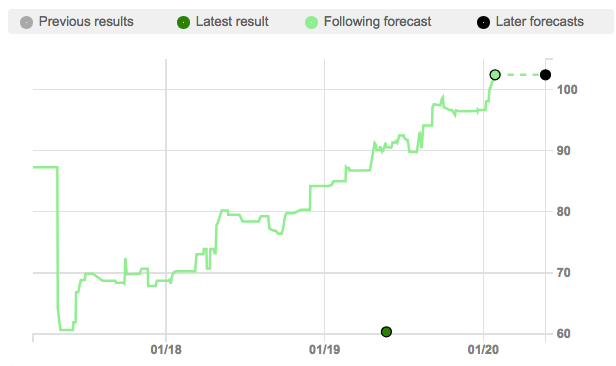

The shares joined the stock market at 50p and within twelve months had dropped to 22p when the company warned that revenue had advanced by ‘only’ 25%. Investors have since never looked back and the shares are up 14-fold from the low:

Amazingly enough, Boohoo’s £3.8 billion market cap now exceeds the £3.5 billion market cap of retail stalwart Marks & Spencer. Loyal Boohoo shareholders will probably not mind the absence of a dividend since the float.

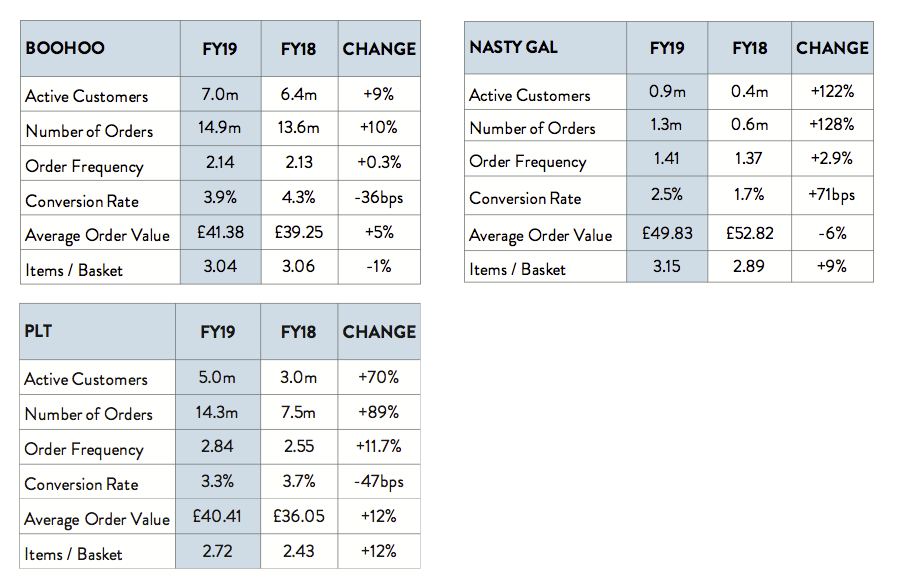

Boohoo publishes some handy statistics:

The stats for the main Boohoo brand indicate the average price of items purchased is £13.61 (calculated by dividing the £41.38 average order value by the 3.04 items per basket). The PrettyLittleThing and NastyGal brands sell clothes at a £15 to £16 average.

(Note that these order values include VAT and other sales taxes. However, reported revenue excludes VAT and is also adjusted for refunds. Revenue per customer and per order may therefore be a better guide to Boohoo’s underlying progress.)

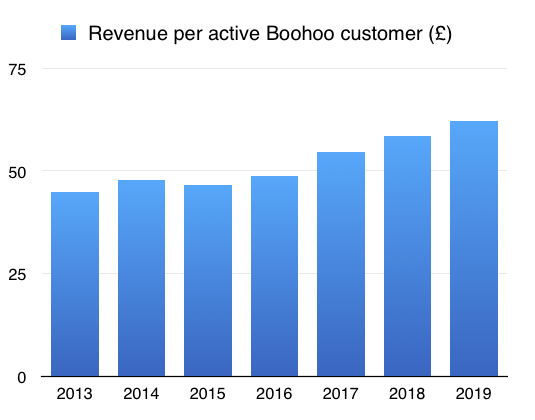

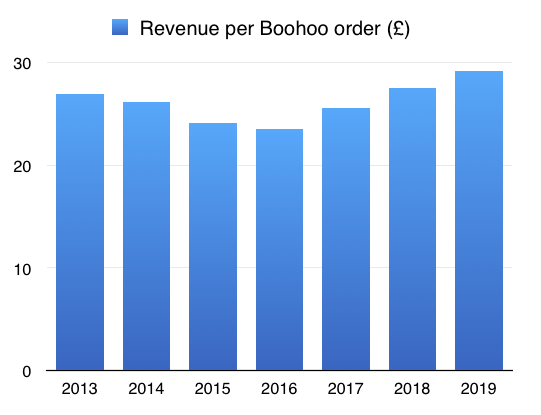

For the main Boohoo brand, both revenue per active customer and revenue per order have improved during the last few years:

Boohoo’s SharePad Summary

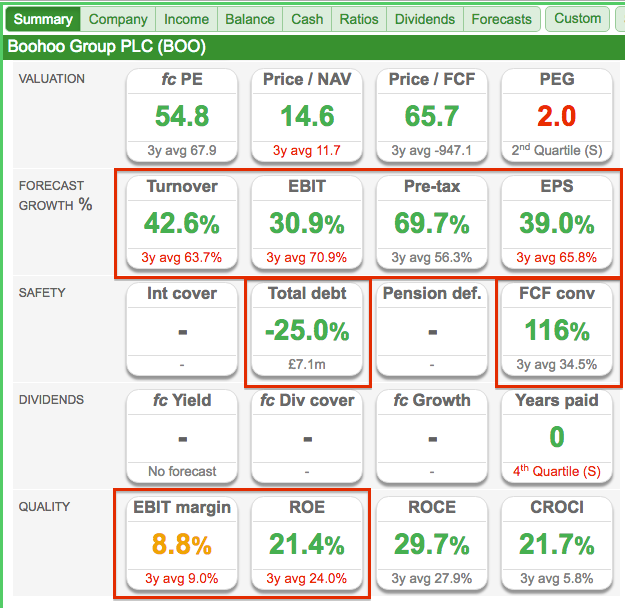

The SharePad Summary for Boohoo is shown below:

The main observations are:

- Extremely positive growth forecasts for the current year (second row);

- Minor debt and super free cash conversion (third row), and;

- The modest margin and robust ROE (fifth row).

Let’s start with those working-capital movements and the cash conversion.

Working capital, accruals and refunds

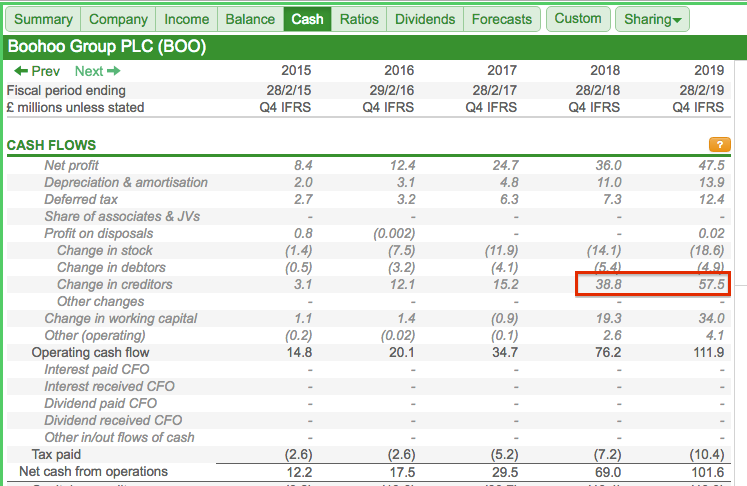

SharePad’s Cash tabs reveals more details about Boohoo’s working-capital movements:

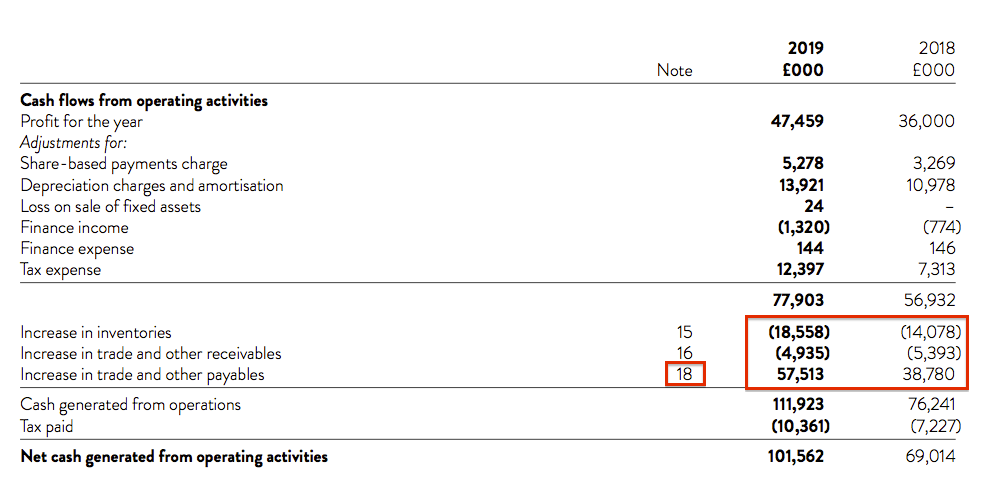

The change in creditors entries for 2018 and 2019 underpin the extra cash generation.

The 2019 annual report is required to understand what these figures represent.

This extract from the annual report contains the actual working-capital movements:

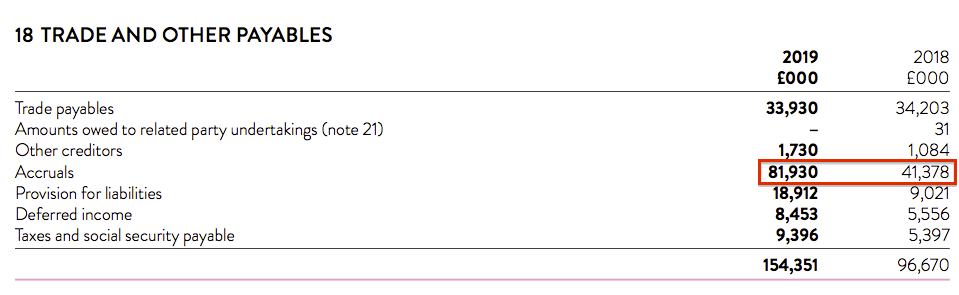

The extract says Note 18 contains more information about the creditor movement. Note 18 is shown below:

The accruals entry has increased by £41 million to £82 million, and looks responsible for boosting Boohoo’s cash flow.

These accruals represent expenses that have been charged to earnings, but have yet to be invoiced to Boohoo and therefore yet to be paid for.

The annual report does not explain what the accruals consist of. The only mention of ‘accruals’ is contained within this line:

“Working capital has reduced primarily due to an increase in payables and accruals relating to our increased trading activity.”

Help comes from Tony Shiret, an analyst at Whitman Howard, who asked about accruals during Boohoo’s 2019 results presentation.

Boohoo’s finance director said the increase was due to:

- Extra suppliers, such as a recent third-party logistics partner that serves the group’s new Sheffield facility;

- The completion of a warehouse automation project, the final payment for which had not been made by the year end, and;

- “Quite high” stock accruals.

The FD’s comments imply the company can defer paying up to £82 million for logistical services, new machinery and fresh stock until some time after their delivery.

These arrangements suggest Boohoo enjoys a strong operational position that gives the firm the upper hand over suppliers — and which should be reassuring for shareholders.

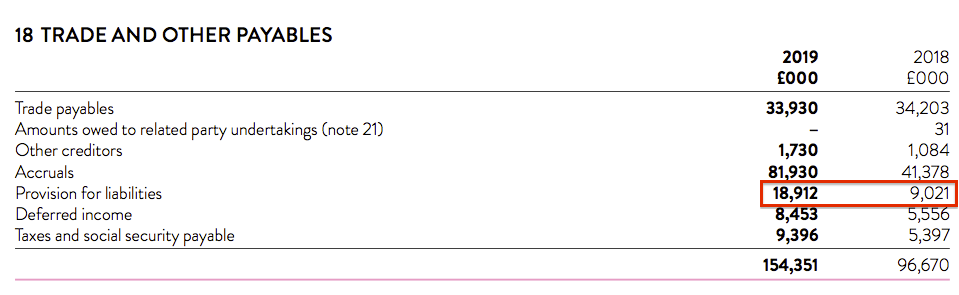

An interesting snippet from Note 18 covers the ‘provision for liabilities’:

This £19 million entry is almost entirely represented by the expected cost of refunds for clothes sold just before the year end.

The £19 million has been charged against earnings, but the cash refunds have yet to paid.

(Note that the refund provision doubled during 2019 while revenue gained 48%. The refund provision continually growing much faster than revenue might indicate increasing levels of returns and possibly lower future margins).

Cash conversion and capital expenditure

Boohoo’s cash-conversion percentage (black line, right axis) has not always been as high as the 116% reported for 2019:

We already know Boohoo’s working-capital movements are favourable, which means the inconsistent cash conversion is due to significant capital expenditure.

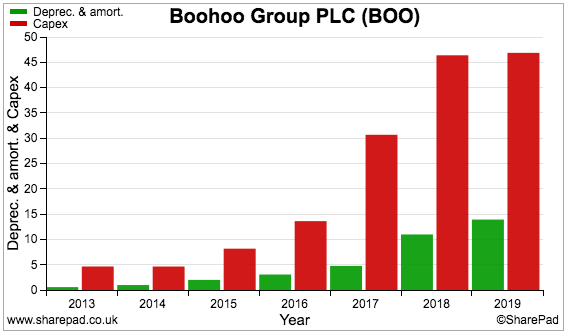

The following chart compares actual cash capital expenditure with the associated depreciation and amortisation charged against earnings:

Between 2015 and 2019, £111 million was spent on capital expenditure that was not charged against earnings as depreciation or amortisation

At least the hefty capex — used mostly to develop new distribution facilities at Burnley and Sheffield — appears justified given the group’s booming revenue and share price.

In fact, Boohoo reckons the enhanced infrastructure ought to cater for sales of £3 billion — more than triple the sales level of 2019:

“We continue to invest in our infrastructure, with our operations at Burnley and Sheffield representing significant stepping stones as we build towards creating a distribution network capable of generating £3 billion of net sales globally.”

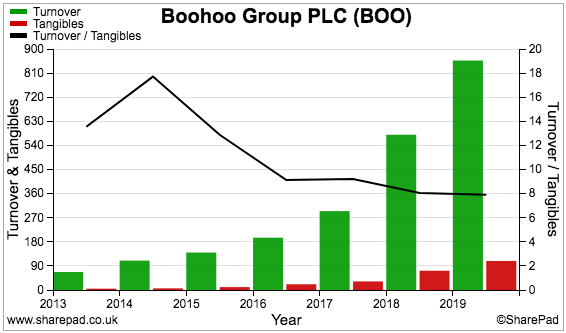

The sizeable capex has meant revenue now represents approximately eight times tangible assets (black line, right axis):

If revenue can be maintained at eight times tangible assets, then Boohoo needs to spend a further £267 million or so to reach that £3 billion sales capacity.

Spending a further £267 million to sustain extra sales of £2 billion and perhaps extra profit of £100 million seems like a good capital-allocation decision to me.

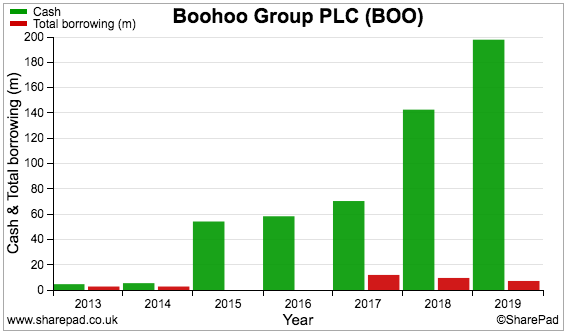

Despite the substantial capital expenditure, cash in the bank has soared while only modest amounts of debt have been utilised:

ROE and margin

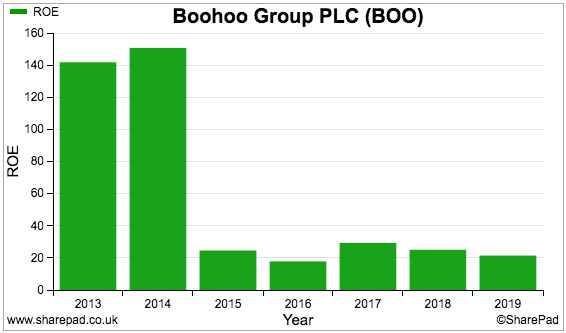

Return on equity tops a welcome 20%, implying the significant capex is earning a good return:

(The startling ROE drop after 2014 is due to the flotation, which raised a net £50 million for the business and expanded the equity base approximately six-fold.)

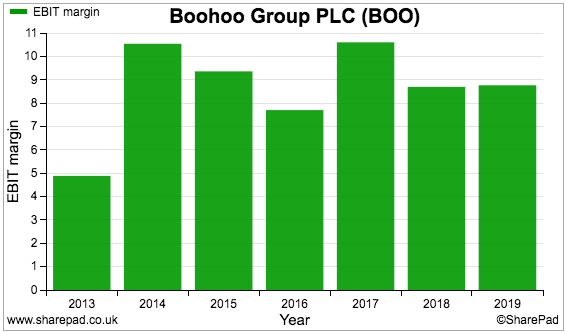

At 9%, Boohoo’s operating margin does not indicate an obvious competitive ‘moat’:

I suppose selling dresses for £6 and offering unlimited deliveries for £10 a year does not leave vast room for profit.

Although Boohoo’s 9% margin can’t match that of Next — which converts a superb 15% of retail/online sales into profit — it does exceed the latest margins for JD Sports Fashion, M&S, ASOS, Frasers (the old Sports Direct), SuperDry and Joules.

Management, shareholdings and lifestyle

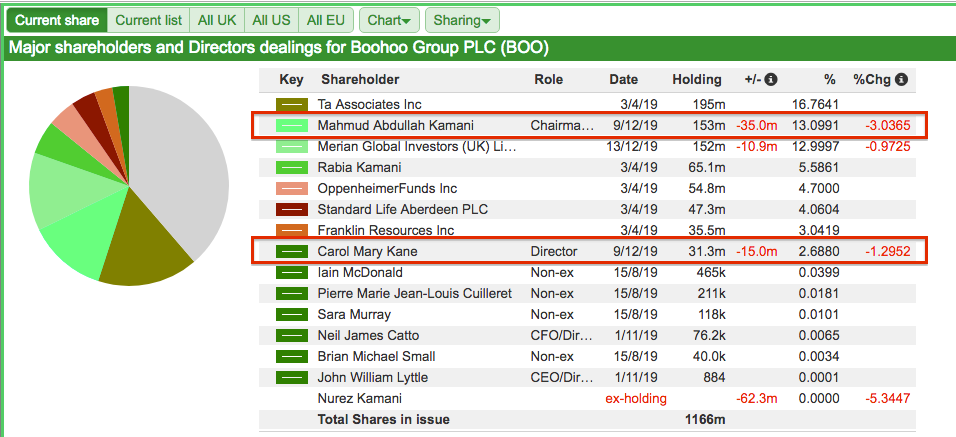

The aforementioned Mr Kamani and Ms Kane continue to serve as Boohoo executives.

Between them the pair control approximately 16% of the company — a combined stake worth almost £600 million — and both appear to be the founder/entrepreneurial leaders that so often reward outside investors.

Mr Kamani and Ms Kane reduced their holdings during December at 285p, and have sold approximately 40% of their shares since the flotation. Both are still in their 50s, so could serve on the board for some time to come.

Members of Mr Kamani’s family enjoy an aggregate 12% holding that sports a £470 million value.

Family members include sons Umar and Adam Kamani, who founded fashion website PrettyLittleThing in 2012 and sold two-thirds of this business to Boohoo in 2016 for £3 million.

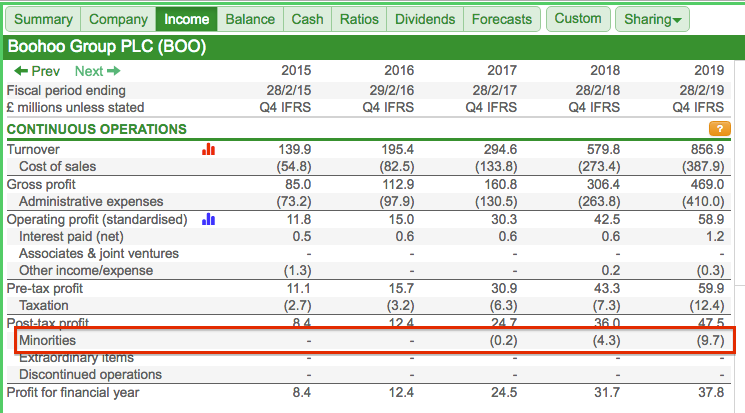

SharePad’s Income tab shows minorities of £10 million for 2019:

This £10 million represents the earnings attributable to the third of PrettyLittleThing that Boohoo does not own — and implies PrettyLittleThing delivered total earnings of close to £30 million.

Earnings of £30 million sound enormous given Boohoo paid only £3m for its PrettyLittleThing stake a few years ago.

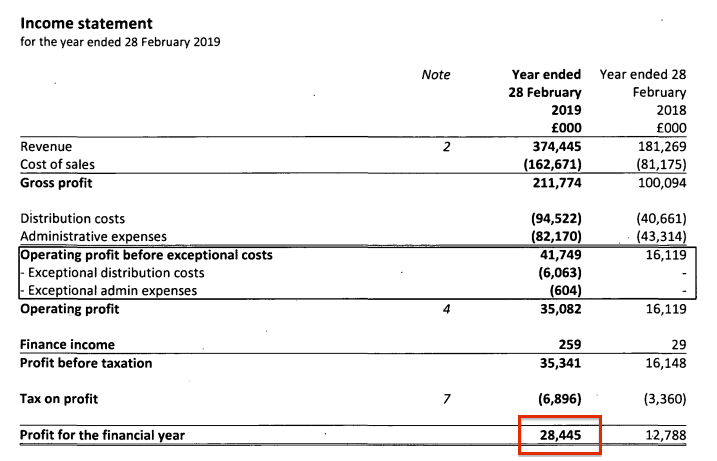

Sure enough, Companies House confirms PrettyLittleThing reported a £28m profit for 2019:

The numbers point to PrettyLittleThing supporting half of Boohoo’s entire profit — which is remarkable given the subsidiary is only eight years old.

Seasoned private investors may bristle at PrettyLittleThing’s boss, Umar Kamani, being no stranger to social media and the celebrity lifestyle:

Mind you, Umar Kamani did tell The Guardian: ”I know my life looks glamorous on Instagram but I put up what I choose to put up. I don’t post pictures of my meetings or reading through data and speaking to America until 1am or 2am in the morning.”

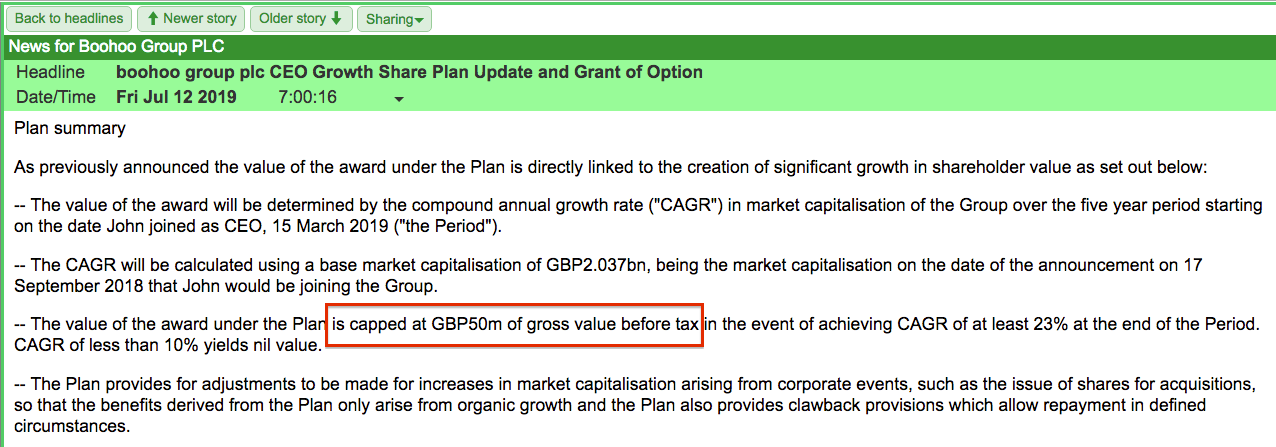

Boohoo’s chief executive — John Lyttle, a former Primark director — could join the Kamanis and Ms Kane as major shareholders within the next few years. Mr Lyttle’s LTIP pays out up to £50 million:

Boohoo’s market cap has to compound at a 23% annual average during the five years to March 2024 for the £50 million to be paid in full. The 2019 AGM saw a 31% protest vote against the board’s remuneration.

Recent trading, forecasts and valuation

If Boohoo’s recent trading statements are anything to go by, that £50 million LTIP payout seems likely to be achieved.

Last April the group’s 2019 results predicted 2020 sales growth of between 25% and 30%. The guidance was lifted during September to between 33% and 38%, and was raised again last month to between 40% and 42%.

SharePad tracked the resulting profit upgrades throughout last year:

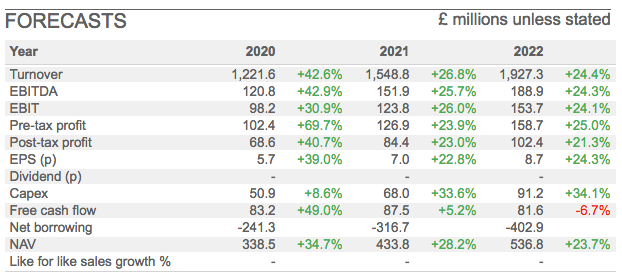

And SharePad’s present forecasts look like this:

The City projections are based on Boohoo’s own “medium-term guidance to deliver sales growth of 25% per annum and [a] 10% EBITDA margin”.

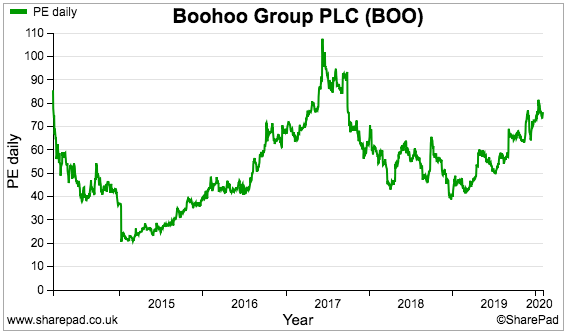

The all-round optimism has left the shares trading at approximately 70 times trailing earnings:

The forecast multiple based on the earnings expected for 2020 is 55.

Assume the 2020, 2021 and 2022 forecasts come good and then:

- Revenue grows at 25% per annum during 2023, 2024 and 2025, and then at 20% per annum until 2030, and;

- Operating margins are held at 8% throughout…

…a case could be made for earnings of £600 million by the end of the decade. Perhaps that £3.8 billion market cap may not be so rich after all.

Mind you, investing at such a lofty rating will not suit everyone.

Nor will headlines such as:

- Boohoo and Missguided among the worst offenders in sustainability inquiry,

- Dark factories: labour exploitation in Britain’s garment industry;

- Love Island star Molly Mae’s Instagram post banned by ASA;

- ‘Send nudes’ Boohoo ad banned after complaint, and;

- Private jets, parties with Khloe Kardashian, and $1 million weddings: Inside the lavish lives of a billionaire fast-fashion dynasty.

At least nobody can quibble about Boohoo’s favourable working-capital cash flow.

Until next time, I wish you happy and profitable investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Disclosure: Maynard does not own shares in Boohoo.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.