Updated: August 2024

We did a little bit of cash flow analysis in the last chapter. In this one, we look at the cash flow ratios that ShareScope calculates for you and what they can tell you about a company’s financial performance.

The key issues that this chapter will point out are:

- Cash flow is not the same as profit

- Cash flow is probably more important than profits

- Cash flow is a great check on the quality of company profits

- You can use cash flow to check the safety of your dividend payments

This chapter will be quite detailed but hopefully, after you’ve read it you’ll be well on the way to becoming a better investor.

As with balance sheets and income statements, we turn the numbers from them into useful information by calculating ratios. You don’t need to spend lots of time doing this, as ShareScope does all the work for you.

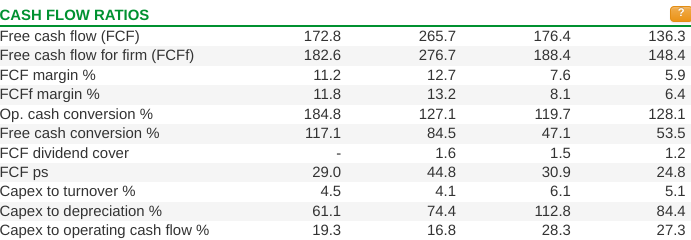

Howden’s main cash flow ratios are shown in the table below.

One thing that you will notice is there are lots of ratios based on what is known as free cash flow. I’ll explain more about this shortly but in simple terms, it is the amount of spare cash a company has left over after it has paid all its essential costs. This will include items such as wages, interest, tax and spending on new assets to replace old ones and to expand the business.

What’s left over the company is “free” to do whatever it pleases with it. It might use it to pay dividends, buy back shares, buy new businesses, pay off some debts or simply retain it.

For many, free cash flow is what investing is all about. Unlike profits, which can be manipulated by a stroke of a pen (such as changing a depreciation policy for example), free cash flow is much harder to manipulate over the long haul (it can be done in the short run)

Remember:

A company can’t pay bills and dividends with profits. It needs to generate cash.

It is often argued that the value of any business is the amount of free cash flow that can be taken out of it for the rest of its life expressed in today’s money. That’s why investors spend a lot of time looking at free cash flow and estimating what it will be in the future.

This is impossible to predict with any real accuracy for most businesses, but that doesn’t mean that free cash flow isn’t a very important measure of company performance. It’s something that you should pay very close attention to.

What is free cash flow?

There is no universally accepted definition of free cash flow because some analysts quibble over some of the numbers involved but most are broadly similar. There are two measures of free cash flow that you need to be familiar with:

- Free cash flow to the firm (FCFf) – the spare cash for all providers of finance

- Free cash flow to Equity (FCFe) – the spare cash for shareholders

In ShareScope, we use the terms FCF and FCFf so I’ll use these terms for the rest of this chapter..

Free cash flow to the firm (FCFf)

This is the amount of cash left over after a company has paid the taxman and paid for the purchases of fixed assets (capex). For a UK company, free cash flow to the firm (FCFf) is calculated as follows:

FCFf = Operating cash flow + dividends from joint ventures -tax paid – capital expenditure – repayment of leases

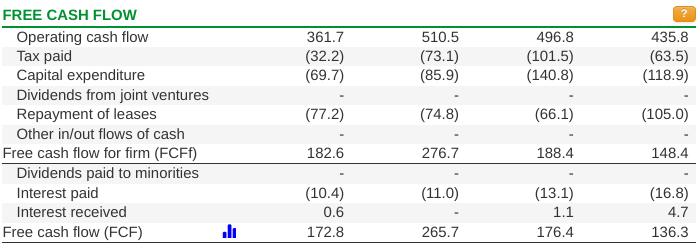

In the cash flow section of ShareScope, it shows you how a company’s free cash flow has been calculated. Howden’s calculations are shown in the table below.

For Howden in 2023, its free cash flow to the firm was £148.4m which was £40m lower than in 2022. This is the amount of money available to pay all providers of finance in a business – interest on debt and dividends to shareholders.

The lower FCFf number in 2023 can be explained by lower operating cash flow and higher lease payments.

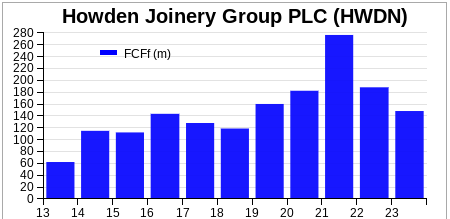

The chart shows that Howden’s FCFf has grown substantially between 2013 and 2023 but the trend has been quite lumpy and has fallen for the last couple of years. You need to go and find out why this is happening. By looking back at the cash flow statement we can see that in the last two years:

- Operating cash flow is much lower

- Capex is higher

- Repayment of leases – capex with a different name – are higher.

It’s normal to expect a company’s free cash flow to move around from year to year. This is mainly due to the fact that investment in the business (capex) tends to be a bit lumpy depending on the company’s plans for expansion and how many existing assets need replacing. A growing company may also invest in working capital to boost sales which may temporarily reduce free cash flows.

While most investors will focus on cash flows to equity, FCFf is a very useful number because it ignores the way a company is financed as interest paid on debts is not deducted.

This makes FCFf a good measure for comparing different companies with different mixes of debt and equity finance. It shows you the surplus cash generated by the business as a whole. This makes FCFf the cash flow equivalent of the EBIT profit measure.

Free cash flow to Equity (FCF)

This is a number that good professional investors spend a lot of time looking at. As I said above, it’s the amount of cash left over after a company has paid the interest on borrowings, taxes, capital expenditure and preferred shareholders (who get paid before ordinary shareholders do). It’s the cash that is ultimately available to pay you a dividend on your shares.

ShareScope calculates FCF as follows:

FCF = FCFf+ interest received – interest – preference dividends – dividends paid to minority shareholders

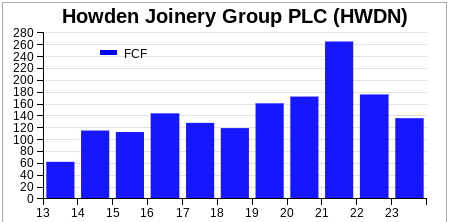

For 2023, Howden generated £136.3m of FCF down from £176.4m in 2022.

As expected, it has followed a similar pattern to FCF but has also come down slightly due to rising cash interest payments.

Free cash flow is a very useful number, but for it to have more meaning and value for investors it can be used in a number of financial ratios.

How to use free cash flow numbers

Hopefully, you will now understand a bit more about what free cash flow actually is in practice. The real use of free cash flow to an investor comes from when they use the numbers to dig deep into the company’s finances.

In the next section, I’m going to show you how you can use free cash flow to check on:

- The quality of a company’s profits

- The safety of its dividend payout

All the numbers you need to do this are already calculated for you in ShareScope.

Free cash flow and profit quality

It’s a lot harder today for companies to fudge their profits than it was twenty years ago. Accounting standards are arguably tougher than they were. Yet, from time to time, we do get revelations that a company’s profits were not as good as they told investors they were.

Such news can devastate the share prices of the company concerned, but often investors could have saved themselves the pain by picking up some warning signs from the company’s cash flow statement.

As an outside investor, you will never really know how a company’s profit figures are arrived at but there are numbers that you can crunch to give you some idea if all is well – or not. This is where cash flow in general and free cash flow in particular comes in.

Probably the best sign of a company’s profit quality is how good it is at turning those profits into cash. ShareScope looks at this in two ways:

- Operating cash conversion – comparing operating cash flow with operating profits

- Free cash conversion – comparing free cash flow to equity with normalised post-tax profits. Or free cash flow per share with normalised earnings per share.

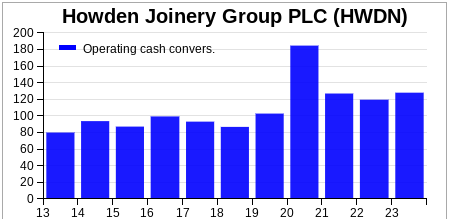

Operating cash conversion

This looks at how effective a company is at turning its operating profits into operating cash flow.

Operating cash conversion = (Operating cash flow/Operating profit) x 100%

For companies with lots of tangible fixed assets (and therefore lots of depreciation to add back) you would expect the cash conversion to be over 100%. If a company’s operating cash flow is regularly below 100% – due to working capital outflows – this might be a warning sign and could be grounds for not investing in it.

Howden’s performance in turning its operating profit into operating cash flow over the 2013-23 period has been generally satisfactory given that it has grown the size of its business considerably. It has been over 100% for the last five years.

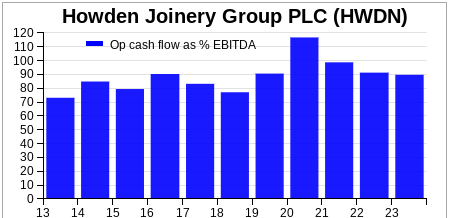

We could also look at a more tougher measure of operating cash conversion by comparing operating cash flow with EBITDA as both have depreciation and amortisation added back.

This looks acceptable. If the conversion was consistently below 80% then perhaps there would be grounds to question the strength of the business – for example, it may be too working capital intensive.

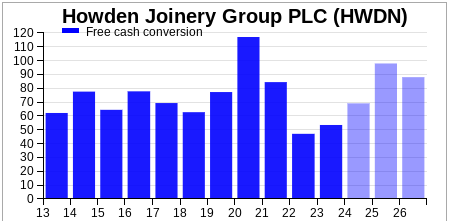

Free cash conversion

This is a really important ratio that ShareScope calculates. It compares a company’s normalised earnings per share (EPS) figure – something people pay a lot of attention to – with its free cash flow per share – something people ought to pay a lot more attention to but often don’t.

Free cash conversion = (Free cash flow per share/Norm EPS) x 100%

A hallmark of a company with very high-quality profits is when a large chunk of its earnings per share turns into free cash flow. As a rough rule of thumb, you want to see free cash flow per share at 80% of the EPS figure.

The caveat to this is that you must be careful not to penalise a company investing for future growth. Highly profitable companies can invest for growth even while generating strong free cash flows. Sometimes though a company will invest so much money in new assets that its free cash flows will be negative.

This is fine as long as the money being ploughed into new assets now can generate strong cash inflows in the future. We’ll revisit this issue very shortly.

Where you really need to worry is if a company is not growing its revenues but has weak or negative free cash flows. Such companies often contain a lot of risk for shareholders.

Howden’s free cash flow conversion record has not been great. It averaged 73% over the 10 years to 2023 and was only 53% in 2023. This is something that definitely requires further investigation to see if it is anything that investors should worry about.

Quite often, poor free cash flow conversion is associated with large capital expenditure cash flows.

Capital expenditure (capex) and why free cash flow and EPS rarely match

Apart from profits and working capital, the most important determinant of a company’s free cash flow is how much money it ploughs back into its business in buying new assets and replacing existing ones that have worn out. This is known as capital expenditure or capex for short.

A company’s fixed assets can last for a long time but many of them don’t last forever. They have to be replaced if the company is to stay in business. If a company wants to grow and become bigger it may have to spend more money on assets. This causes cash to flow out of the business.

Two of the key questions that you need to ask as an investor is: How much money does a company need to spend to stay in business? How much is it spending on expanding?

Stay with me on this. It might get a bit complicated but hopefully, it will all make sense in the end.

When a company like Howden buys an asset it has to depreciate it and charge this as an expense against its revenues which reduces profits.

Depreciation can be seen as an estimate of how much you need to spend each year to replace your existing assets and keep them up to date. So when a company’s EPS is calculated it has had depreciation taken away as an expense. This makes a lot of sense when working out how much profit shareholders in a business really earn.

But remember, depreciation is not a cash expense. The cash flows out of the business when assets are purchased. We can see this in the cash flow statement with the capex number. This is the number that is deducted when we calculate free cash flow to equity (FCF).

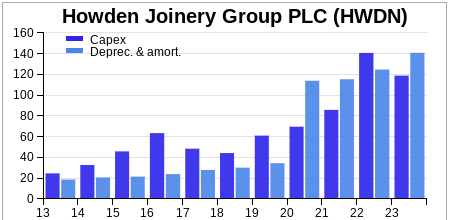

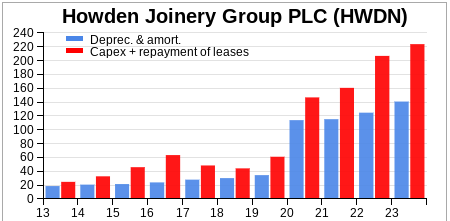

What we need to compare is the amount spent on capex in the cash flow statement with the depreciation charge in the income statement. ShareScope does this for us. The figures for Howden for the last ten years are shown in the chart below:

This chart shows something that an investor should take time to understand.

Before 2020, Howden typically spent more on capex than its depreciation expense as it was growing its business by opening up more customer depots.

It has kept on doing this after 2020, yet capex has been lower than depreciation in all but one of the last four years. This does not make sense. A bigger number of depots will increase the ongoing depreciation expense while existing and new depots will need money spent on them.

What has changed is the accounting treatment for leases.

Howden takes on new depots under long-term rental or lease agreements rather than buying them outright. If it bought them outright there would be a big outflow of cash when it did so. Under a lease, this does not happen but there is a repayment of the asset rented at the end of the lease agreement.

Before 2020, all lease expenses went through the income statement. Now the annual rental payment is counted as capex, but the repayment at the end of the lease is classified as a finance expense.

If we ignore this lease repayment, then FCF will flatter companies that lease rather than buy assets. This is why it is included in the calculation of FCF in ShareScope.

As you can see, when it is included, Howden has been spending considerably more than its depreciation expense in recent years which is why its FCF has been weak.

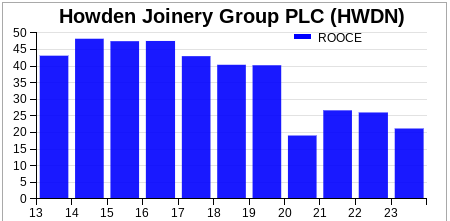

Spending on new assets is something that investors should welcome if it generates profit and cash flow growth in the future. One way of checking out how well a company’s investments are performing is to look at its return on operating capital employed (ROOCE). This compares a company’s profit or EBIT with the money it has invested in its operating assets.

As a rough rule of thumb, a good ROOCE is 15% or higher. This would suggest that spending money is making the company’s investors better off.

Howden is meeting this criteria – note pre 2020 numbers do not include leased assets on the balance sheet – but only just. Investors will hope that as new assets mature and become more profitable that returns will improve.

The other thing to watch out for with companies is when capex is less than depreciation. This may mean that a company is generating lots of free cash flow. But it may also mean that it is not replacing its assets. If it does this for too many years then the business may start to deteriorate.

Free cash dividend cover

A company needs spare cash to pay dividends. If it doesn’t have this then it may have to borrow money or sell assets to pay shareholders. This cannot go on forever and only usually delays the day of reckoning when the dividend has to be cut or even stopped altogether.

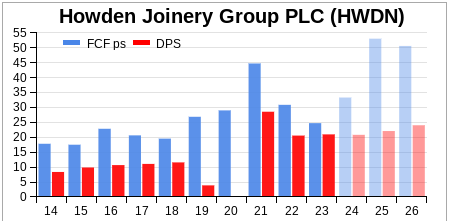

ShareScope calculates free cash dividend cover by comparing free cash flow per share with the dividend per share.

Free cash dividend cover = (free cash flow per share/dividend per share)

Howden has a decent track record in generating enough free cash flow to pay its dividend as its free cash flow per share has usually exceeded its dividend per share by a comfortable margin.

Deteriorating free cash flow in recent years has seen that margin decrease. However, according to forecasts from City analysts in June 2024, Howden’s free cash flow per share was expected to increase significantly, increasing the safety of the dividend payout in the process.

Why ShareScope ignores asset sales when calculating free cash flow

Some investors add back the money received from selling assets when they calculate free cash flow. ShareScope does not.

It is not always wrong to include the proceeds from selling assets in the calculation. In some businesses (such as car rental, property and pub companies) there are meaningful asset sales made every year and it would be right to include these.

ShareScope is trying to be conservative. Asset sales for lots of businesses can be very irregular and may distort an investor’s view of a company’s ability to generate cash if they were included in the calculation of free cash flow.

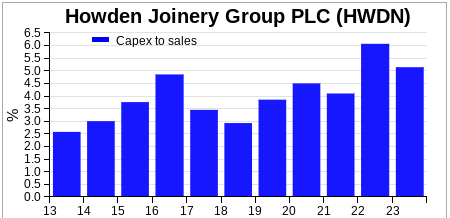

Capex to turnover

As well as comparing capex with depreciation, you can also compare it with the company’s sales or turnover. This is a measure of capex intensity – the percentage of sales it is ploughing back into the business.

Look at this ratio over a long period of time so that you have a chance of spotting changes in a company’s business. If capex as a percentage of turnover is rising, find out why. Is it because the company is expanding or is it because the cost of replacing assets has gone up? Compare this ratio with companies in the same line of business to see if capex levels are different.

The beauty of ShareScope is that it allows you to go back a long way and study a company’s finances. This can be very enlightening.

As you can see, Howden has been increasing its capex as a percentage of turnover in recent years. The chart understates the ratio as it excludes the repayment of leases discussed above.

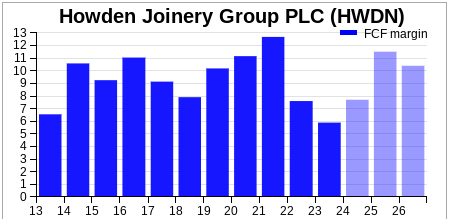

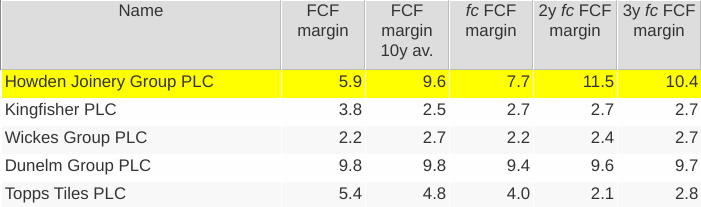

Free cash flow margin

If you are comparing companies then looking at how much of their turnover they turn into free cash flow can be a good way of measuring a company’s financial performance. The bigger the percentage of turnover turned into free cash flow – the free cash flow margin – the better.

Free cash flow margin = (Free cash flow to Equity/Turnover) x 100%

Howden’s free cash flow margins have come down as its free cash flow has fallen as its revenues/turnover has increased. Its FCF margins are expected to improve according to analysts’ forecasts at the time of writing.

Howden also compares favourably with the free cash flow margins earned by its sector peers. That said, Dunelm comes close to matching it and has a slightly higher 10-year average on this measure.

Other uses of free cash flow

We can use free cash flow to calculate other investment returns and to look at the valuation of a company. I’m going to leave that for another chapter.

Next: Chapter 8 – Is this a good business?

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.