Updated: August 2024

The last couple of chapters have focused on two particular styles of investing – value investing and dividend investing. Both these approaches to owning shares are largely based on the current state of a company – its profits and its dividends.

In this chapter, we are going to turn our attention to a different approach – growth investing. Growth investing is different in that it is mostly about what will happen to a company’s profits in the future. When practised well it can lead to tremendous profits for investors.

Just like any other investing approach, there are some standard rules to follow and some pitfalls to look out for. ShareScope can also help you to identify some potential companies whose shares could be worth a closer look for growth investors.

What is growth investing?

There are a few definitions out there. But a broad description of what growth investing is involves investing in the shares of a company whose profits have grown strongly in the past and are expected to keep on doing so in the future.

Unlike the shares favoured by value investors, growth shares tend to have high PE ratios and pay very small or no dividends.

They are more commonly associated with smaller rather than larger companies. However, as we have seen recently with the growth of artificial intelligence, some of the world’s largest companies such as Microsoft and Nvidia can be growth stocks as well.

Growth and value investors are trying to do the same thing. They are trying to buy a share for less than it is ultimately worth (described in investing circles as its intrinsic value) but go about doing this in a different way.

The best way to show this is with an example.

How growth investors hope they will make money

First, let’s look at how a value investor tries to make money. Value investors look to buy shares that the stock market has beaten down to a low price (relative to its earnings or assets) but they think have the potential to recover.

Let’s take a share trading at a price of 50p with earnings per share of 10p and therefore trading on a low PE multiple of just five times (50p/10p).

The value investor thinks that earnings can grow at 5% per year and that eventually the stock market will put a higher PE multiple on them. This kind of scenario is shown in the table below.

| Year | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPS (p) | 10 | 10.5 | 11 | 11.6 | 12.2 | 12.8 |

| % growth | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% | |

| PE | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Share price (p) | 50 | 63 | 77 | 93 | 109 | 128 |

| Overall gain | 155% | |||||

What happens here is that the stock market realises that it has overreacted and realises that the company is a reasonable – albeit steady – business. Over time, the PE multiple attached to the earnings per share goes up from 5 times to 10 times. After 5 years, the shares are trading at 128p – a gain of 155%.

Now let’s look at how the growth investor hopes to make their fortune.

| Year | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPS(p) | 10 | 12.0 | 14.4 | 17.3 | 20.7 | 24.9 | 61.9 |

| % growth | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% | ||

| PE | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Share Price(p) | 200 | 240 | 288 | 345.6 | 414.7 | 497.7 | 1238.3 |

| Overall Gain | 519.2% |

Here, the investor is also buying a share where the EPS is 10p. However, the share price is 200p – a PE of 20 times – because the company has seen rapid growth in its profits which is expected to continue.

What the investor is hoping is that EPS will grow at 20% for the next ten years and that the stock market will continue to price the shares at 20 times EPS (or a PE of 20). If it does then the share price will rise from 200p to 1238p – a gain of 519%.

Just as the magic of compounding works with dividend investing, the same applies to growth investing. Compounding years of high growth in profits can add up to big profits for the investor.

Most value investors wouldn’t dream of paying 20 times earnings for a share – unless the earnings were very depressed and could recover – but what you can see above is that if profits grow fast enough for long enough, paying what looked like a high price can deliver a much more impressive performance.

The caveats here are that to win at growth investing, not only do profits have to keep growing but the price of those profits – the PE ratio – has to stay high as well.

As we shall see later, if growth slows down, the PE ratio will probably fall – known as PE multiple contraction – which can result in the investor losing a significant amount of money.

As an interesting aside, Benjamin Graham was known as the father of value investing. In fact, he made most of his money from a growth investment in the form of a car insurance company called GEICO (now owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway). The profits from owning GEICO made Graham more money than all his value investments put together.

How to spot a growth company

This is not easy to do.

Growth investing can make investors rich but it’s very easy to be sucked into thinking you are buying into a growth company when in reality you are not.

What in fact you might be doing is buying into the hope of something good happening in the future.

There’s no shortage of companies on the stock exchange that are long on hope but short on profits.

For example, there are lots of oil exploration companies that aren’t making any money but could do in the future if they find oil. These companies are not growth companies but a speculation.

So how do you go about finding a growth company to invest in?

Sales growth

The first place to start is to look for companies that have grown their sales strongly in recent years – say by at least 15% per year for the last five years. Why are sales so important?

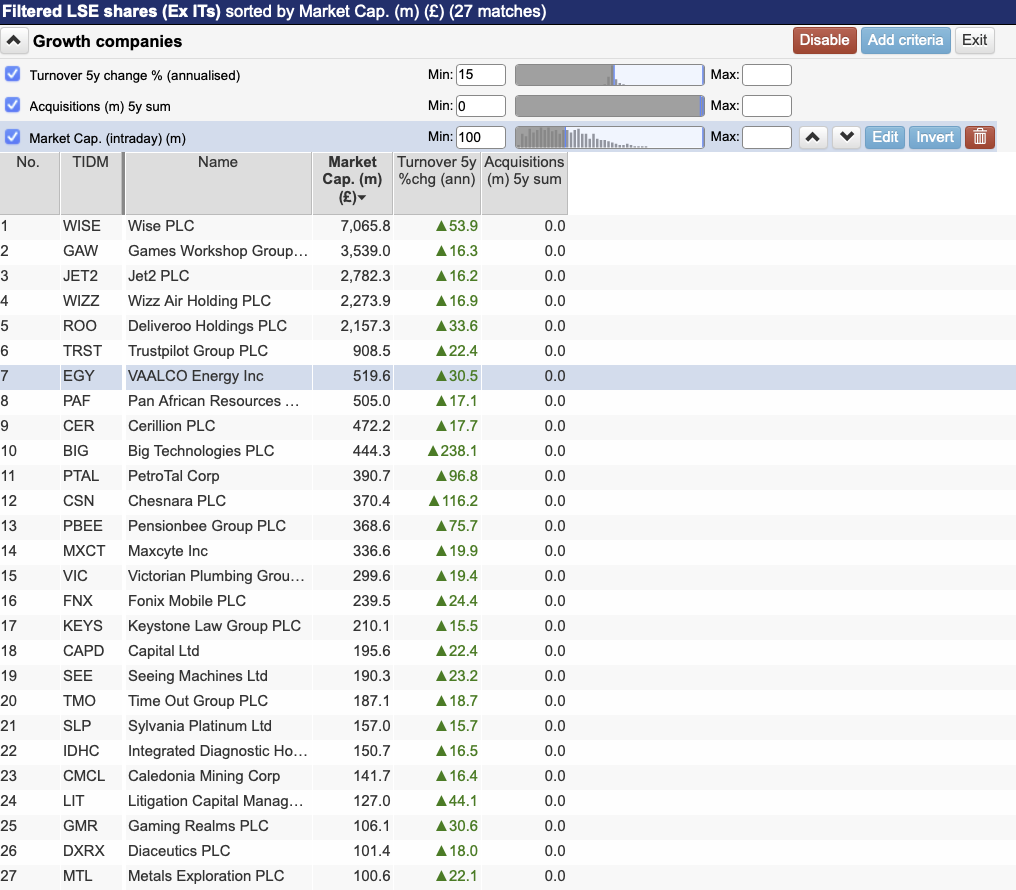

Above is a ShareScope search for companies that have grown their sales at an average of 15% a year for the last five years and have not made any acquisitions to do so.

The minimum value of the company has also been set at £100m which avoids many shares that are harder to invest in – due to liquidity issues. It gives us a list of 27 shares.

Genuine growth companies grow by selling more, not by cutting costs or buying other companies. When you are looking at a company, the first question you should ask is:

Can it sell a lot more stuff in the future?

If you think it can then the company has cleared its first hurdle in becoming a growth share for you to invest in.

Once you find companies, you then have to work out how sales and profits can continue growing.

This is difficult and involves a certain amount of guesswork as no-one can perfectly predict the future. You need to understand what the company sells and the markets it sells into.

Is there sufficient pent up demand to keep sales growing in the future?

To answer this question you need to work out what the “growth drivers” are.

For example, demand for a service or product may be supported by demographics (a trend relating to the general population) such as ageing.

Another example is a new technology such as superfast broadband where the current take up amongst households is quite low and has the potential to increase significantly or artificial intelligence.

Another avenue to explore is for companies that may have developed a new product that is cheaper and better which can take a lot of sales off existing companies in the same market.

Past growth in sales is all well and good, but its future growth that matters when it comes to selecting growth shares.

Very few companies can keep high rates of sales growth up for a long period of time, so you need to be careful that you do not set the future sales growth criteria too high as you might not fine many shares to invest in.

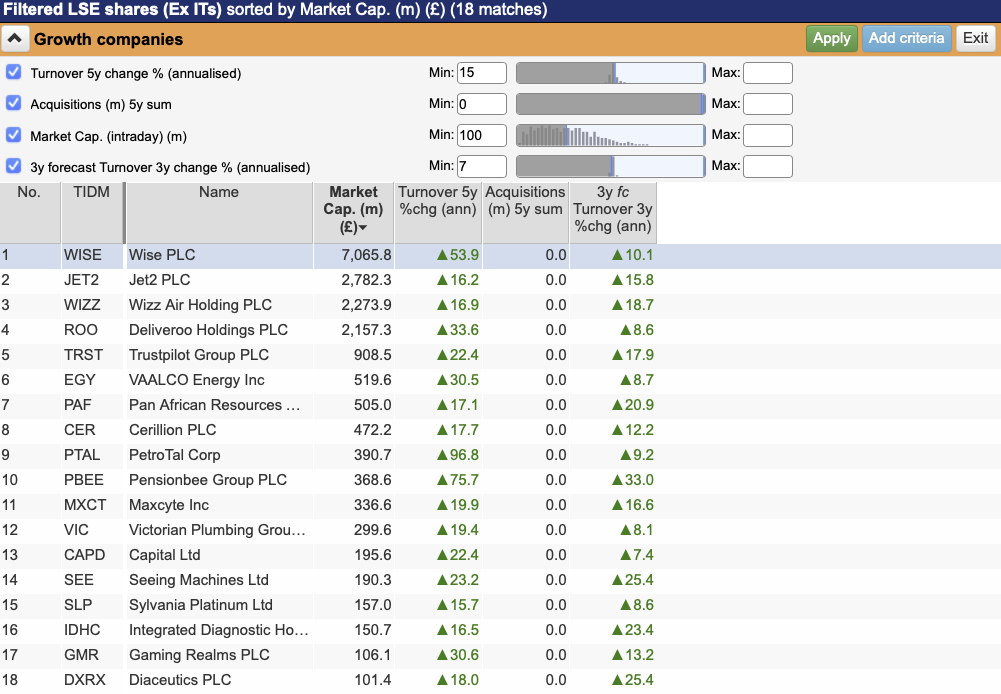

Setting a target of 7% growth is decent as it would allow a company to double its sales over the next decade.

Asking ShareScope to find companies with average sales growth of at least 7% for the next three years – the limit of its forecast range – reduces the size of our list down to 18 shares,

Does the company have a big moat?

We all know that some castles have moats. Those big ditches of water represent a castle’s first line of defence against intruders. The bigger and deeper it is, the better.

Good companies are no different. They have what are known as economic moats – something that stops the competition from eating its lunch.

Strong growth for a product and high profits made by the companies selling it tends to attract attention.

To be successful, a company needs something to stop fresh competition entering the market and beating down profits – it needs a moat.

The airline industry has seen a growing demand for its services for years but many airlines have struggled to consistently make money and often lose it.

Why?

Because it has been too easy for new airlines and aircraft to enter the market and push down fares. In short, there isn’t a big enough moat. So how do you spot a company with a decent moat?

Companies with economic moats are highly sought after.

They are central to the investing philosophies of people such as Warren Buffett. According to Buffett buying these types of companies is a great way of reducing your risk as an investor.

That’s because what has allowed it to make lots of money in the past will probably mean it has a very good chance of doing so in the future.

By owning – at the right price – these businesses for a long time the investor can compound the high returns it makes and potentially become very rich.

That’s why Buffett invested lots of money in companies such as Coca-Cola, Gillette and American Express – they had big moats.

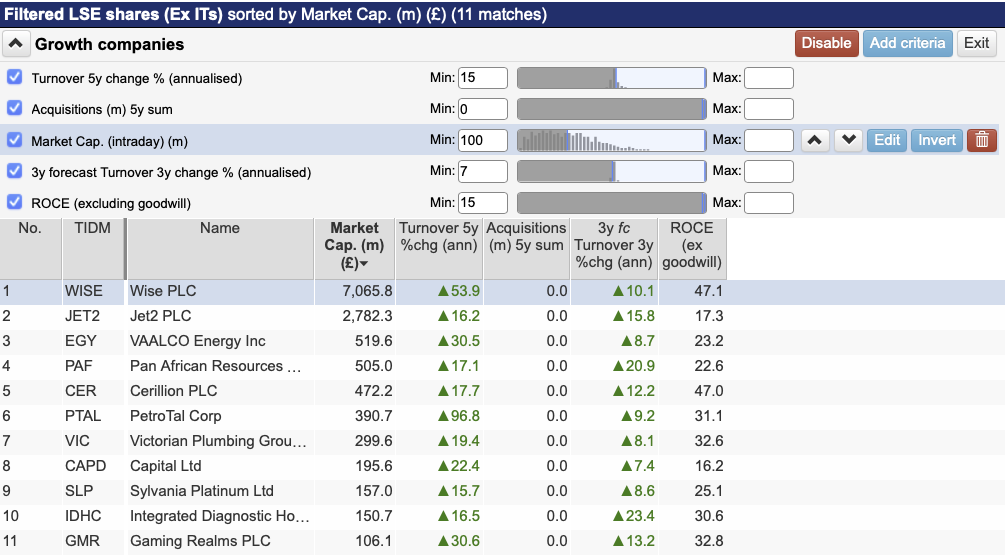

One of the most straightforward ways to identify a company that might have an economic moat is to look for ones with consistently high returns on capital employed (ROCE). You can easily do this with ShareScope.

Good companies earn lots of profit as a percentage of the money they invest. However, high returns attract competitors who want a slice of the cake.

So if a company has had a high ROCE (say more than 15% as a bare minimum) that suggests that it could have a moat that offers a strong defence against competition.

Asking ShareScope to select companies with a minimum return on operating capital employed (ROOCE) of at least 15% reduces our search down to 11 qualifying shares.

It’s all very well looking at numbers. But it’s also important to understand what lies behind them. There are lots of things you can look for which explain the existence of a moat.

One of the chief reasons is the existence of branded products. Brands are a symbol of quality that customers identify with and often stay loyal to because they trust them. They can take years to build up and can be defended with large advertising budgets that a prospective competitor would struggle to match.

Related to brands are products that are habit forming such as a particular brand of tobacco or alcoholic drinks or products that are deeply entrenched within a business such as Microsoft Office software.

Here, users are very loath to change their habits because of the hassle of doing so which means a lot of repeat business for sellers.

Patents are another example. These protect products such as prescription drugs or technologies from competition for a period of time. They explain why pharmaceutical companies have had very high returns. However, bear in mind patents do not last forever. They are also of little use if a better product comes along.

Look for companies that might have cost advantages. The sheer size of a company can give rise to what is known as economies of scale.

This often means that they can spread the cost of making something over lots of units so they can make things cheaper than smaller competitors.

They may also be able to buy goods and services cheaper as their size allows them to obtain bigger discounts with suppliers.

The management of a company should not really be seen as a moat. A moat usually comes from a company’s assets and products. That’s not to say that good management doesn’t matter. It does.

However legendary US investor Peter Lynch offered some good advice when he said, “invest in a business that any idiot could run because some day one will.”

Finding companies with moats is more straightforward than buying the shares of them. That’s because lots of people know about them and bid up the price of their shares. Buying a great company at too high a price is one of the biggest mistakes an investor can make and usually ends in disappointment. I’ll show you an example of how this can work out shortly.

You have to be patient when buying good companies. You need to buy them when they suffer a temporary setback or when the stock market is crashing. In the meantime building a watchlist of great companies to buy is time well spent.

Smaller companies grow faster than big ones

Famous investor Jim Slater once said ?elephants don’t gallop?. By this he meant that big things don’t tend to move very fast. The same can be said for big companies. It is much more difficult for a company valued at £10 billion to double in size than it is for one worth just £50 million or less.

This is why smaller companies tend to be a fertile hunting ground for growth investors. They do come with more risk attached to them – such as being difficult to sell when bad things happen – but they can present some fabulous opportunities to make money from the stock market.

The risks of growth investing

Investing in shares is risky. Growth investing comes with its own particular set of risks. I’ve set out what I think are the most important risks that you need to pay attention to below.

Bad sources of growth

As I’ve said earlier, good growth comes from selling more goods or services. But companies can grow their profits by other means and not all of this is good.

You may look back at a company’s profit history and it seems that profits have been growing rapidly but on closer inspection you find that the company has a habit of buying companies (known as growth by acquisition).

Some acquisitions can be good for shareholders if done at the right price with the right business, but they are often used to hide the fact that the company’s underlying business is slowing down or not growing at all. You have to ask yourself, what happens when a company stops buying other companies? What happens to its growth?

Profits can also grow by cutting costs rather than growing sales. Managements often have a plan to improve the profits of the business by making it leaner and more efficient.

This can deliver big growth in profits for a while until the scope for cutting costs runs out. If you see a company with impressive profits growth without sales growth then this may be telling you that the quality of growth isn’t that good.

A lot of investors pay attention to the growth in earnings per share (EPS). This is fine if EPS is growing because sales and profits are growing. However, the annual bonuses of lots of company managements hinge on hitting EPS growth targets.

One way they can help themselves meet them is by reducing the number of shares in issue so that EPS grows faster than the growth in underlying profits. Management does this by spending money to buy back the company’s shares and then cancelling them.

Sometimes a share buyback is good for shareholders if the shares are purchased at cheap prices and give a good rate of return on the money spent. However, too often management buys shares at very lofty prices and even though EPS goes up, the rate of return can be quite low and a bad use of shareholders’ money.

Growth in EPS due to buybacks has been increasing in recent years. You mustn’t be fooled into thinking that this is automatically a good source of growth that makes a company an attractive growth investment.

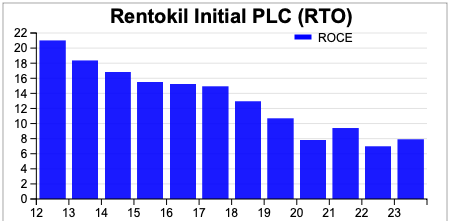

Watch out for a company where EPS has been growing but return on capital employed (ROCE) has been falling. This can be a warning sign that something is going wrong.

If ROCE was 60% but has fallen to 45% that is still a very high rate of return and probably nothing to worry about unless the fall has been very sudden. But if a company had a ROCE of 15% which is now 9% that is more of a problem.

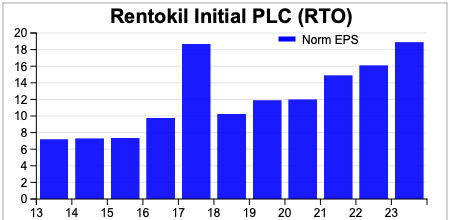

Pest control company Rentokil is a good example of this in recent years. EPS has been increasing but ROCE has been falling.

EPS can still increase up if the company is spending large amounts of money (because the extra profits are more than the extra interest costs on the extra money borrowed and invested) but the declining ROCE may be a sign that a company is losing its competitive edge or has some other problem.

In Rentokil’s case, a large acquisition in the US has caused it a lot of problems.

Paying too much for growth

Right at the start of this chapter I mentioned that growth shares tend to have high price tags attached to them – such as high PE ratios. This can work out if the expected profits growth comes through, but what if it doesn’t?

Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s people bought internet companies with PEs of more than 100 or with no earnings at all. When the companies concerned couldn’t produce the profits implied by the high prices paid for their shares, share prices collapsed. Many companies went bankrupt. Even with the ones that survived, many investors still haven’t got their money back yet.

One of the biggest risks facing growth investors is when growth slows down from its previous high rate and the PE ratio attached to the earnings falls. This is known as PE multiple contraction and it can devastate shareholder returns.

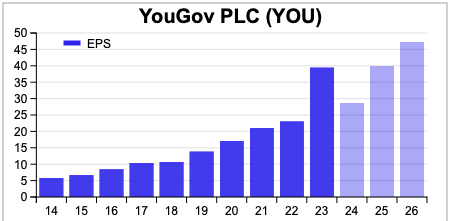

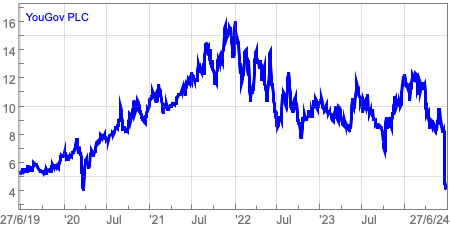

YouGov’s PE ratio collapses after a profit warning

For years, data and research company YouGov was loved by investors for its high rates of profit growth and its shares had a very high PE multiple attached to them.

A profit warning in June 2024 meant that EPS was expected to fall rather than grow which causes the PE ratio – which had been coming down – to collapse.

As a result, Yougov’s share price collapsed back to levels of five years ago,

Yougov is a clear example of the risks of paying high prices for growth stocks.

Returning to our list of stocks from the ShareScope filter, we can add some valuation data to them such as PE ratios and PEGs to see if we can buy shares at attractive prices.

Jet2 might be an example of a share that an investor might want to do more research on given its low PE. The PEG of Victorian Plumbing might also peak someone’s interest.

Smaller company risks

Smaller companies tend to be less established than bigger ones. Sometimes this means that they are less able to withstand setbacks such as a downturn in the general economy or the loss of a key customer. They may also find it harder to finance their businesses and may pay more for doing so.

There are also risks involved with buying the shares of smaller companies. Firstly, they can cost more to buy and sell. The difference between the buying and selling prices (known as the bid-offer spread) can often be high. It’s not uncommon to buy a share and find that it would fetch 5% less than you paid for it straight away.

Small company shares can also be more difficult to buy and sell. This is because they can be more tightly held by large shareholders which means there isn’t a large pool of them on the market every day. This is known as low liquidity and is an important consideration if you need to sell in a hurry.

Many smaller companies trade on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) which is managed by the London Stock Exchange (LSE). Taken as a whole, AIM has performed badly over the ten years prior to writing.

Reporting regulations are less stringent on AIM and there is less scrutiny of companies by City analysts. For these reasons, there is more likely to be occurrences of manipulated or even fraudulent accounting.

Looking for growth companies with ShareScope

Using ShareScope is an excellent tool to look for great shares. However, it is important to realise that a filter is just the start of a search and not a list of shares to go out on buy. You might have to run several filters with different criteria to find a share that you are happy with.

There are other ways to look for growth companies.

Good investment ideas can sometimes crop up in unusual places. For example, you might buy lots of things from a shop or a business on the internet because you really like what it sells and the prices it charges.

The chances are that if you like it then others will as well. Sometimes by doing a bit of searching you can find out that the business has shares listed on the stock exchange. Even better, very few big investors might not even know about it so you could have the opportunity to invest before the company starts to grow rapidly.

Do you have the right mindset to be a growth investor?

Whatever strategy you use to invest, the key determinant of whether you are ultimately successful or not is whether you can hold your nerve and stick to your guns. When it comes to growth investing, I’d highlight one particular trait needed to be successful – patience.

Earlier on in this chapter I talked about the power of compounding. Rolling up those high rates of growth over a number of years is akin to rolling a lump of snow along the ground and watching it get bigger.

This is what compounding is all about. But you may have to wait many years for it to pay off ?

Even if the predicted growth is accurate, the markets may be headed the wrong way for a while.

It is not a get rich quick scheme but in the end the market will hopefully reflect company performance. Do you have the patience to wait?

One of the biggest mistakes that an investor can make is selling too soon. They think that the business has had a good run and that it’s best to sell the shares whilst everything is still going well. This is perfectly understandable as you don’t lose money by making a profit.

However, true growth companies can double in value and often double again.

One of the reasons that Warren Buffett has become so wealthy is because he has been very patient with his investments and has lived to a ripe old age.

He has owned many of them for decades and has held on to them because they have remained good businesses. Of course, Buffett’s big advantage over most other investors is that he owns a lot of businesses outright and gets paid all of the annual profits. This gives him a big advantage in compounding the value of growing companies.

For the rest of us whose ownership of companies are subject to the ups and downs of the stock market things are a little different but not that different.

To do well as an investor takes time and patience.

Buying and holding good companies for a long time does work. The only time you might want to consider selling is when a company stops being a good business or if it becomes wildly overvalued in a raging bull market.

Next: Chapter 13 – Investing in bonds

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.