How to measure company returns

In the previous chapter, we learnt that profits and cash received (cash flow) are rarely the same value. We looked at free cash flow conversion which tells how good a company is at converting its profits into free cash – that is, cash available to pay dividends, pay off debts or invest in the business. Free cash flow conversion is a measure of profit quality, accounting transparency and efficiency.

In this chapter, we look at ways to measure how good a company is at generating profits from the resources at its disposal. We will be looking at what the company getting back in profits as a percentage of the money it has invested? This is the real measure of how good a company (or its management team) is.

To find this out we calculate investment returns using a range of return ratios. I’ll explain four popular ratios and which ones I prefer.

For those of you that are interested in more advanced analysis, I’ll also show you how you can break up some return calculations to find out even more about a company.

Companies are just like savings accounts

The best way to look at a company’s financial performance is to keep things simple and compare it to a savings account. Most of us know that a bank account paying 5% interest is better than one paying 2%. Well, companies are no different.

If a company invests £10,000 in a business (the equivalent of putting money in a savings account) and get backs £1,000, its return (or interest rate) is 10% (£1,000 divided by £10,000). What you should be looking for as an investor is to buy the shares of a company that earns a consistently high interest rate. Or you could look for a company with a low interest rate that has the potential to earn a higher one.

One thing to bear in mind is that different sectors of the economy will have different returns or interest rates. For example, a company that makes computer software is largely dependent on the brains of its employees to make money and will tend to have less money invested in assets. If it is successful then you would expect it to make higher returns than a steel mill which will have a lot of money tied up in buildings, machinery and stocks of raw materials.

So when you are comparing companies, those comparisons will only be meaningful if the companies concerned are in the same line of business. Having said that, by looking across different sectors you may come to the conclusion that it might be better to invest your money in a computer software company than a steel mill.

How to work out a company’s interest rate

SharePad provides you with four key calculations (ratios) to help you work this out. They are:

- Return on capital employed (ROCE)

- Cash return on capital invested (CROCI)

- Return on assets (ROA)

- Return on equity (ROE)

These four ratios all use slightly different measures of profit and money invested. You may wonder why this is. In some cases, it comes down to investor preference or that some ratios are better for particular types of company. I’ll explain more below.

Note that SharePad and ShareScope calculate returns based on the average values of assets, equity, and capital employed/invested.

As you will hopefully see, these calculations can tell you a great deal about a company and whether it could be a good investment or not.

Let’s start by looking at return on capital employed (ROCE), which is probably the best measure of a company’s performance and a number you should definitely look at.

What does capital employed mean?

Capital employed, capital invested and invested capital are terms that are used when calculating company returns. They all mean the same thing – the total amount of money that has been invested in the company.

This includes money invested by shareholders (equity) and lenders (debt) as well as other long-term liabilities such as pension schemes and provisions for future costs.

Capital employed is as the value of the company’s assets less cash, credit from suppliers and credit from the taxman (which are all forms of free short-term financing).

Return on capital employed (ROCE)

ROCE looks at the returns a company makes for all its providers of finance – shareholders and lenders. Go back to chapter 2 to see how capital employed is calculated. ROCE is calculated by using the following numbers:

ROCE = EBIT / Capital Employed x 100%

What this ratio is looking at is the money a company makes before tax (earnings before interest and tax or EBIT) to pay all providers of finance – essentially interest to lenders and dividends to shareholders. It is not distorted by how a company is financed or the rate of tax it pays on its profits as we shall see later with ROA and ROE. This makes it a much better measure for comparing different companies.

Generally speaking, when it comes to ROCE the bigger the number the better. If a company can invest money and earn a high ROCE then over time the owners of the business – its shareholders – should become better off. Remember though, that different companies in different industries will have different values for ROCE.

You should look at the trend of a company’s ROCE to get a feel of how a company has been performing. A trend of falling ROCE needs to be watched closely as it can often be a sign that things are going wrong even if profits and earnings per share (EPS) are still rising.

Why EPS can still go up as ROCE is falling

Consider a company that has EBIT of £2m and capital employed of £20m. It has no debt – the capital employed has all come from equity (money paid for shares by shareholders). Its ROCE is 10% (£2m/£20m). It pays tax on its profits at a rate of 20% (20% of £2m is £400k) leaving it with £1.6m of profit for shareholders. With 2m shares in issue, earnings per share (EPS) is 80p (£1.6m of profit divided by 2m shares).

Let’s say that the company borrows £10m at an interest rate of 5% to buy its main competitor which has EBIT of £600k. Interest payable will be £500k (5% of £10m) leaving profits before tax of £100k. After tax at 20% has been paid, there is £80k of extra profit for shareholders.

So profits for the whole company have gone up to £1.68m or 84p per share. Not too bad you might think. But ROCE has fallen. Total EBIT is now is £2.6m and capital employed is £30m (£20m + £10m) giving an ROCE of 8.67% (£2.6m/£30m).

The lesson here is that a company only needs a ROCE on new investments which is more than the interest rate on new borrowings to increase profit (EPS). However, ROCE measures the firm’s efficiency at converting invested cash into profit. Profit may have gone up but, because some of it has been paid out in interest, the % return (ROCE) is lower. This is not usually a good sign.

A high ROCE that has been sustained for a long period of time is usually a sign that you are looking at a very good business. However, a high ROCE can be a warning sign too. That’s because it can attract competition which wants to grab a slice of those high returns. It’s very important that when you find a company with a high ROCE that you dig a little deeper into its business and satisfy yourself that it can keep the competition at bay.

For many years, Tesco looked like a very solid business with ROCE in the mid teens percentage range. ROCE was 16.2% in 2006 has fallen to 11.4% in 2014 and looks like it will trend lower still given its well publicised problems.

We’ll look at Tesco’s ROCE in a little more detail later on when we get into more advanced analysis tools.

Cash return on capital invested (CROCI) – where ROCE and FCFf meet

As we discussed in the previous chapter, free cash flow is a useful number to calculate but on its own doesn’t mean that much. ROCE is good at calculating a return on all the money invested by a company. CROCI combines the two and gives a cash return which actually means something.

CROCI = Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF) / Capital Employed x 100%

This ratio is great for spotting companies that are good at turning their profits into cash but comparing it with a measure of money that has been invested by a company. It’s another way of calculating a company’s interest rate on its investment. High rates of CROCI may tell you that you have found a very good business with high quality profits.

The first thing to discuss here is which definition of free cash flow you have to use to calculate CROCI. You should use free cash flow to the firm (FCFf).

FCFf is the amount of surplus cash available to provide all providers of finance – lenders and shareholders. Capital employed is the total amount of money invested by lenders and shareholders. So you are comparing the money invested by them with the money that belongs to them.

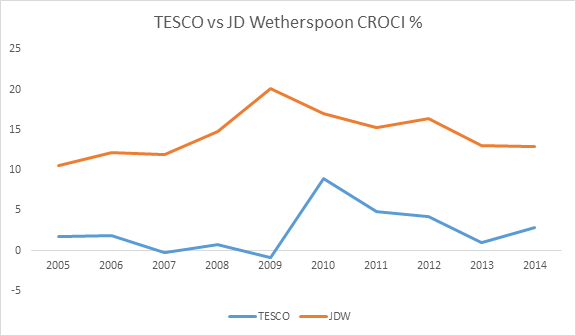

Tesco’s poor cash flow performance shows up in a low CROCI. On the other hand, JD Wetherspoon scores much better on this measure.

If you have negative free cash flow to the firm you will have a negative CROCI. Should you worry about this?

As I said in the last chapter, not necessarily. All companies tend to make big investments from time to time which will eat up all their cash flow and more. It’s the future cash inflow that those investments will produce that matters. If a company spends cash today so that it can earn a higher CROCI in the future then a year or two of negative free cash flow (and negative CROCI) shouldn’t be anything to worry about. Years and years of low or negative CROCI is another matter though. That would be a sign that a management’s strategy is not very effective at growing the value of the company.

ROCE and CROCI are probably the best two measures of company returns. Having said that, they don’t tend to work too well with financial companies – such as banks – which have lots of assets and lots of debt. For these companies, return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) are probably better.

Return on assets (ROA)

You can calculate ROA in a couple of ways but the most common method is:

ROA = Profits after tax / Total Assets x 100%

This is looking at what shareholders are getting in profits as a percentage of the total assets employed.

Total Assets is the biggest number that you will usually see on a company’s balance sheet. It will include items such as land, buildings, intangible assets, current assets and cash – essentially everything a company owns or has a claim on. It can be seen as a broad approximation of the money that has been invested in a business, but will not take away free financing items such as cash balances and credit from suppliers as capital employed does.

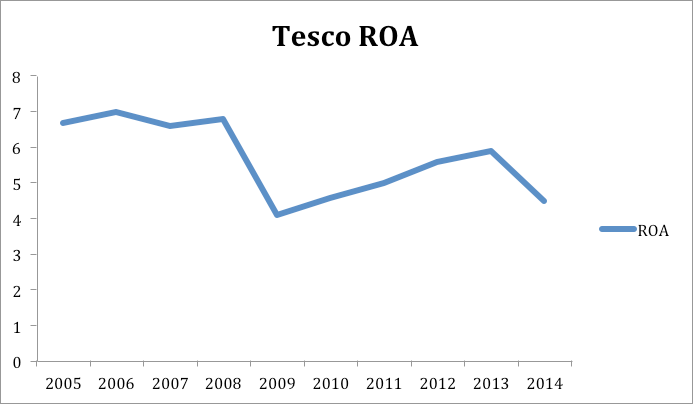

In 2014, Tesco’s ROA was 4.5% – not a very high number. As we have seen with lots of measures of Tesco’s financial performance, this has been on a downwards trend in recent years as profits have been falling.

Return on equity (ROE)

This is similar to ROA but instead just looks at the profits for shareholders made by a company on the money that shareholders have invested or its equity.

ROE = Profits after tax / Total Equity x 100%

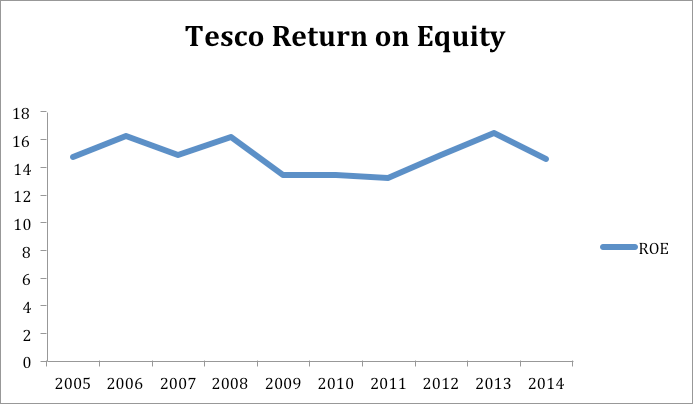

Despite lower profits and a falling ROA, Tesco’s return on equity looks to have been remarkably stable over the last decade. So what’s going on? Could the ROE be telling us that Tesco is still a good business despite its problems?

Sadly, I don’t think this is the case. That’s because ROE – like lots of other measures – can be distorted by how a company is financed. It’s back to the issue of debt again. The more debt – or more gearing – that a company has the bigger the effect on ROE. I’ll explain why in the next section.

Feel free to skip the next section if you just wanted to learn the basics. The advanced stuff does get a little bit more complicated but it can help you learn a lot more about a company and its potential.

Advanced analysis – how debt distorts return on equity (ROE)

One of the great benefits to an investor of crunching numbers and calculating financial ratios is that they can often be broken down into smaller bits. For example, return on equity can be broken down as follows:

Return on Assets x Financial Gearing = Return on Equity (ROE)

Let’s look at this a little more closely. We know the calculation for ROA (Profit after tax/Total Assets) whilst financial gearing in this case is measured by Assets/Equity.

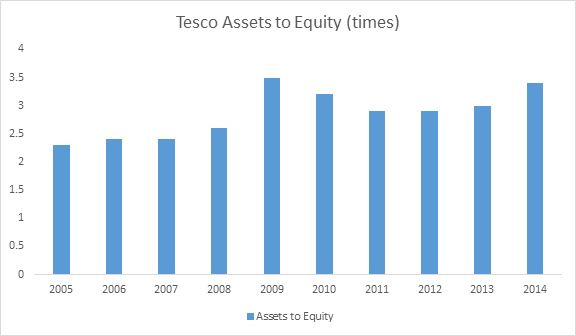

Assets to equity explained

Assets to equity is a measure of gearing (leverage). It tells you how many times larger a company’s assets are compared with the equity invested by shareholders. You can also work out your own personal gearing in the same way if you want to.

Let’s say two neighbours, Sarah and Jane, have bought identical houses (the asset) valued at £100k. Sarah has invested £5k of her own money (her equity) and borrowed £95k via a mortgage to buy the house. Jane has put in £50k of her money (her equity) and borrowed the rest.

Sarah is geared 20 times (£100k/£5k) whilst Jane is only geared twice (£100k/£50k). If the value of the house goes up 5%, Sarah’s equity will go up by 100% (5×20 or £105k – £95k = £10k). Jane’s equity will go up by only 10% (5×2 or £105k – £50k = £55k).

The gearing also works in reverse: Sarah’s equity will be wiped out completely with a 5% fall in house prices whereas Jane’s will not. Sarah’s higher gearing means she is facing a much higher risk. The same is true with companies.

If we list all the ratios together what you will see is this.

(Profits after tax / Total Assets) x (Total Assets/ Equity) = (Profits after tax/Equity)

Now, I don’t want to take you back to a school maths lesson too much but for those of you who know a little bit about basic algebra will understand that the Total Assets on the bottom half of the first equation (ROA) and the top of the second equation (Financial Gearing) cancel each other out. This proves that ROA and gearing when multiplied together equal return on equity.

What this means in practice is that ROE can be juiced up by increasing financial gearing. If you were just to look at ROE in isolation you might miss this.

This is what has been going on at Tesco.

In 2005, Tesco was 2.3 times geared. In 2014 this had increased to 3.4 times. Even though its ROA has fallen, ROE has stayed broadly the same. The reason? Higher gearing. So when you are looking at ROE, don’t automatically assume that because the number has increased that the business has improved. Have a look at the company’s gearing. It might just be taking more risk than you’d like it to.

Banks – low returns and lots of gearing

However, if you want a starker example of how leverage juices up returns to shareholders then look no further than a bank during the last decade or so.

On the basis of cold, hard numbers, banks aren’t really that profitable at all. They have very low returns on their assets. The only way that they have been able to make acceptable returns on equity in the past is by having lots of gearing.

Banks have lots of gearing chiefly because the money that customers deposit with them is a liability. Banks use this money as a source of finance in exactly the same way as borrowing from another bank or investors – it is debt.

Have a look at the record of Barclays between 2000 and 2013 in the table below:

| Barclays plc | ROA (1) | Assets to Equity (2) | ROE (1×2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 0.79% | 21.38 | 16.90% |

| 2001 | 0.79% | 24.39 | 19.30% |

| 2002 | 0.65% | 26.25 | 17.10% |

| 2003 | 0.66% | 26.46 | 17.40% |

| 2004 | 0.56% | 32.1 | 17.90% |

| 2005 | 0.32% | 37.84 | 12.00% |

| 2006 | 0.35% | 36.39 | 12.70% |

| 2007 | 0.28% | 39.33 | 10.90% |

| 2008 | 0.04% | 43.3 | 1.80% |

| 2009 | 0.15% | 23.58 | 3.60% |

| 2010 | 0.18% | 23.93 | 4.30% |

| 2011 | 0.41% | 23.98 | 9.90% |

| 2012 | -0.08% | 24.81 | -2.10% |

| 2013 | 0.10% | 20.52 | 2.00% |

As you can see, ROA is not very impressive. Starting at 0.79% in 2000 it continued to trickle down throughout the decade. The most revealing column is what has happened to assets to equity. Starting out at an already high 21 times it went higher and higher but was not enough to stop ROE from falling after 2004.

By the time of the financial crisis in 2008, Barclays was over 43 times geared. Since then it has been reducing that gearing which in 2013 was back to around the same level it was in 2000. However, ROA is still very low and so is ROE.

It begs the question as to how high ROE can be without high amounts of leverage and financial risk? This issue could be a reason why the shares of banks are not very popular these days.

Capital turnover explained

Capital turnover is the value of sales (or turnover or revenue) generated per £ of capital invested in the company (or $ for US companies). It is a useful measure of how effective a company’s investments are and the effectiveness of its strategy. Capital turnover is a major determinant of a company’s ROCE. For a UK company, a capital turnover of 0.3 means that the company is generating 30p for every £1 invested. A rising capital turnover ratio can be a good sign whereas a falling one can be a sign of trouble ahead (or a change in the company’s activities).

Breaking down ROCE into smaller parts

Just like ROE, you can break down ROCE into smaller parts as follows:

ROCE = EBIT margin x Capital Turnover

Or

(EBIT / Sales) x (Sales/Capital Employed) = (EBIT/Capital Employed)

As with the breakdown of ROE into smaller bits, the Sales numbers cancel each other out so multiplying a company’s profit margin (in this case EBIT) by its capital turnover will equal its ROCE.

So if you look at the trends in operating margin and capital turnover you can gain a greater understanding into how a company is generating its ROCE.

Let’s have a closer look at Tesco.

| Tesco plc | EBIT margin % (1) | Capital Turnover (2) | ROCE % (1×2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 6 | 2.6 | 15.6 |

| 2006 | 6 | 2.7 | 16.2 |

| 2007 | 6 | 2.6 | 15.6 |

| 2008 | 6 | 2.6 | 15.6 |

| 2009 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 12.88 |

| 2010 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 11.97 |

| 2011 | 5.9 | 2.2 | 12.98 |

| 2012 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 14.08 |

| 2013 | 6.3 | 2.2 | 13.86 |

| 2014 | 5 | 2.3 | 11.5 |

What ROCE teaches you to do is to concentrate on more than just the income statement. If you did just that, you might look at the EBIT margin and think that it has been quite stable and that everything was fine. Look at the capital turnover though (the amount of sales a company generates for each £1 of capital invested) and you can see that Tesco has been getting less sales for the money it has invested in the business and this has been dragging down its ROCE. If its profit margin starts falling as well then ROCE can fall quite substantially.

What’s good about breaking down a company’s ROCE between its profit margin and capital turnover is that it gives you an insight into how a company can improve its returns or where it might be vulnerable. If you think about this a bit further, you can see how a company can earn a higher ROCE:

- Higher profit margin

- Higher capital turnover

- Higher profit margin and capital turnover

Capital turnover and profit margins are related to each other. For example, a company with a high profit margin and low capital turnover could try to increase its ROCE by cutting its prices – and possibly its profit margin – in order to sell more.

A company with low profit margins might want to look at cutting costs or becoming more efficient to boost its ROCE. Another option is to boost capital turnover by getting rid of unproductive assets.

Different businesses in different industries tend to have different profit margin and capital turnover characteristics. One year’s figures should not be taken as a rule, you should examine the trend. Having said that, here is a short list of different companies in different industries with their latest profit margin and capital turnover figures (as of February 2015) to highlight this point

| Company | Industry | Profit margin (%) | Cap turnover(x) | ROCE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reckitt Benckiser | Household Goods | 23.8 | 0.9 | 21.42 |

| BAT | Tobacco | 40.7 | 0.8 | 32.56 |

| National Grid | Utilities | 28.2 | 0.3 | 8.46 |

| Glaxo | Pharmaceuticals | 24.5 | 1 | 24.5 |

| BHP Billiton | Mining | 32.4 | 0.5 | 16.2 |

| Capita | Business outsourcing | 8.6 | 1.6 | 13.76 |

| Lookers | Car retailing | 2.3 | 7.3 | 16.79 |

BHP Billiton and Lookers are highlighted for a reason. They have a very similar ROCE but they achieve it in different ways. BHP has high profit margins and low capital turnover, whereas Lookers has low profit margins and high capital turnover.

The bottom line is this: companies with lots of capital invested – like mining, utilities and manufacturing – need high profit margins to make decent ROCE. Low profit margins are fine as long as you can sell lots to make up for this.

Understanding these issues is to understand the challenge that faces the CEO and board of a substantial company. Excessive emphasis on one or more values like EPS and ROCE can lead to distorting behaviour.

A CEO should aim for all parts of the business to generate as much sustainable profit for as little investment as possible. The CEO has to believe that every division is or is capable of making a return on investment that is above the cost of capital.