Finding good investment ideas among companies that have floated on the stockmarket recently can be like looking for a needle in a haystack. Richard thinks he knows what to look for, maybe it is Moonpig.

Some of my favourite new investment ideas in recent months have been recent flotations, companies like Marks Electrical and Dr. Martens.

Before I introduce another, I should explain why I believe recent flotations can be a good source of new investment ideas despite bountiful evidence that they do not, in general, make good investments.

Flailing flotations

I wrote about the evidence a few years ago.

As a group, firms that have been listed a long time, twenty years or more, perform much better than firms that have been listed briefly, three years or less.

Companies that have been listed for intermediate durations, perform better than youthful firms but less well than the most seasoned.

If we were to randomly select shares from the stockmarket, we could improve our odds of success considerably by restricting the pool of available shares to those that had been listed for more than twenty years.

But we are not investing randomly.

I think long-listed businesses perform better because, almost by definition, they are proven businesses that make money.

Many businesses that float on the stockmarket are young and loss-making. Some of them will never make money.

That is one of the reasons these companies are bad investments.

Another is that without profits or dividends to anchor their valuations, investors get carried away with the story and pay too much for shares.

In general, these shares give flotations a bad name, but hiding among them are established, profitable, household names that are successful businesses hitherto privately owned.

While we will probably want to see a few years of detailed accounts required of listed companies but not of private companies, we will not have to wait twenty years to form an opinion on them.

The sooner we start getting to know these firms, the sooner we can develop the confidence to invest in them.

Finding quality flotations

I find interesting recent flotations the same way I find most of my new ideas, during my near daily scan of all the shares listed in London that have recently published their annual reports.

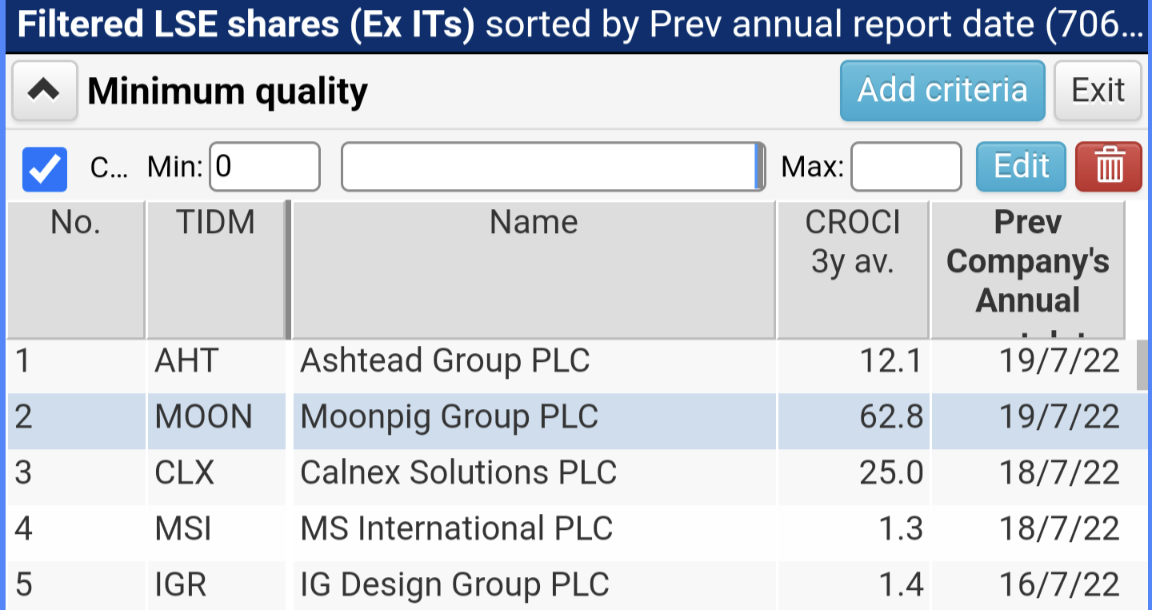

Recently, I have taken to reducing the number of companies for scrutinisation by using a one-factor filter that excludes firms that have not generated cash over the last three years.

To my mind, if a company is not making a cash profit it is not a proven business. It is speculative and typical of many flotations.

Source: SharePad. List: LSE shares (Ex ITs). Filter: CROCI (Average over 3y: min 0). Sort column: Company’s annual report date (Previous).

Moonpig is one of the most recent companies to pass the filter. It is a well-known business that has recently published its annual report and it generates cash.

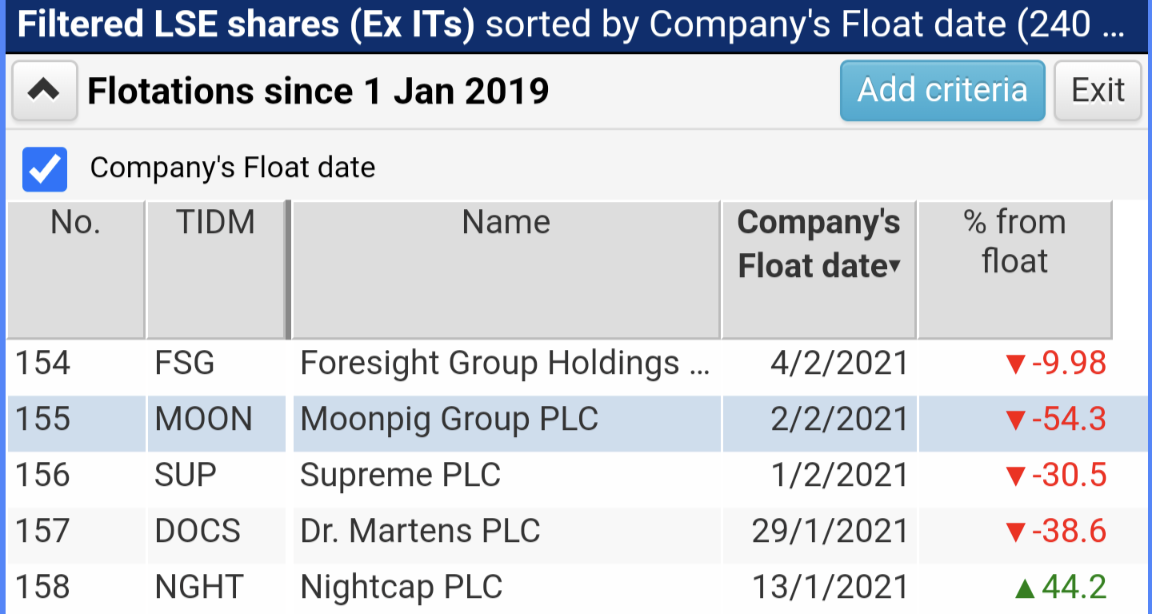

The company floated in February 2021, and since then the shares have fallen 54%.

Source: SharePad. List: LSE shares (Ex ITs). Filter criterion: Company’s float date (From: 01/01/2019 To: 25/07/22). Sort column: Since float (Percentage change).

Moonpig’s performance may resemble a typical flotation, but its cash flows suggest it is more substantive.

If the share price was frothy when the company floated, valuations have deflated. SharePad reports price-to-earnings ratios in the mid-teens.

Moonpig

Most of us know Moonpig as an online seller of greeting cards in the UK, but it aspires to become “the ultimate gifting companion” and also owns Greetz, a Dutch Moonpig acquired in 2018.

The company says revenue from cards amounts to 68% of the revenues of all UK online card specialists.

Growth will require the continued poaching of customers from physical card retailers, and selling more gifts. In the year to April 2022, gifts contributed nearly 50% of revenue.

On the face of it, cards and gifts appeal to the same customers at the same time. The company’s reminder-based marketing systems should work for both, so the expansion into gifting, already well underway, is a logical progression.

But if the company is a substantial company, why the dramatic change of market sentiment?

A big obvious hole in the company’s business model would render the shares uninvestable.

Moonpig’s first full year as a listed company has been a year of contraction, but if that is why traders have gone cold on the stock, it is not a very good one.

Moonpig’s growth in 2021, coinciding with the first year of the pandemic, was exceptional because for much of the year its competitors operating stores were shut, and even when they were open customers were staying away.

People compensated for not being able to see friends and relatives by buying them cards and gifts.

Compared to the year to April 2020, before the pandemic, Moonpig’s revenue in 2022 was 76% higher and its adjusted profit before tax was 55% higher. Since the costs ignored in adjusting profit relate to Moonpig’s flotation, ignoring them probably gives us a better impression of how the business has performed.

Skimming the company’s annual report, I cannot see any indication the business model has been holed in the last year. The company says gifts earn it lower gross profit margins but the impact lower down the income statement is much diminished because gifts require little incremental marketing.

People come to Moonpig to buy cards, and it seeks to flog them gifts too.

There was one significant strategic development mentioned in this year’s annual report, though it occurred after the year-end and so is not yet reflected in SharePad’s historical data.

The company has acquired Buyagift, which owns the UK’s biggest and third biggest experience gifting platforms, Buyagift and Red Letter Days.

Moonpig bills this as an acceleration of its strategy.

The acquisition brings Moonpig thousands of partners, restaurants and activities, that would be taxing to acquire one-by-one. Soon it will be able to offer each card buyer the opportunity to buy a gift experience to include within a card.

This acceleration comes at a cost, £124 million, which is more than double Moonpig’s adjusted profit (EBIT) and more than three times free cash flow in 2022.

Buyagift is profitable, it earned £12 million in profit (EBITDA) or maybe around £10 million in EBIT in 2022.

On the face of it, Buyagift and Moonpig should add up to more than the sum of their parts but it is quite a big deal, and that makes me a little uncomfortable.

It also makes Moonpig the love child of not one but four Dragons Den dragons.

Moonpig was founded by dragon Nick Jenkins. Red Letter Days was founded by Rachel Elnough, an early dragon, and bought out of administration by dragon Theo Paphitis and Peter Jones, the only one that remains a dragon (in the TV sense).

Mr Paphitis and Mr Jones owned Red Letter Days for more than a decade before selling it to Smartbox, owner of Buyagift, in 2017.

Directors leading from the front

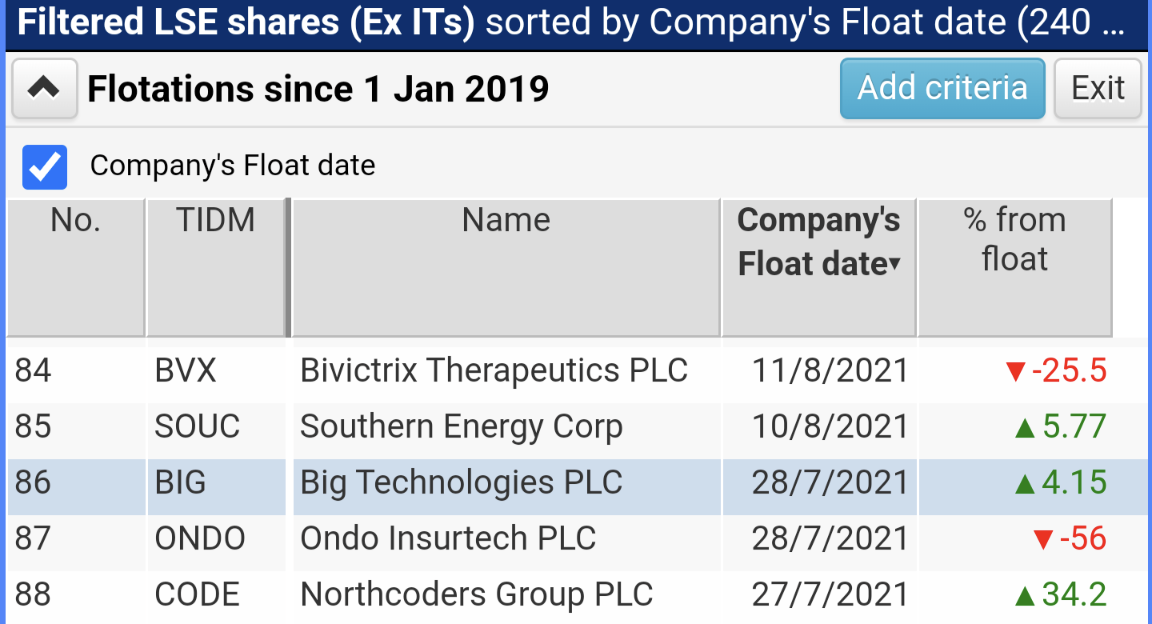

Big Technologies is a recent flotation that passed my quality test in May. The company makes smart tags for offenders and hopes to find other commercial uses for them.

The company floated a year ago, and at the current share price of £2.38 it is trading at just over its float price:

Source: Sharepad

One person who may believe the shares are a good investment is chief financial officer Darren Morris, who so far this year has bought 91,245 shares at average prices of between £2.22 and £2.43.

I do not put much emphasis on directors’ deals but perhaps we can read more into buys than sells, especially when the quantity of shares is significant.

To put large amounts of their own money on the line, directors must be reasonably confident in the prospects of the business. But there are many reasons directors might sell shares that have nothing to do with the state of the business they run.

Let us hope that is the case at Dr. Martens, where the chairman, chief executive and chief financial officer all sold millions of shares earlier this year.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.