Happy New year.

This year, I have resolved to keep things simple, which is not easy in investing.

Aide memoire…

Just before Christmas Chris, a SharePad customer, emailed me with a request:

When I look at company reports which often run to a couple of hundred pages I find the position somewhat daunting…

It would be very helpful to have an aide memoir as to what is considered important to look at in company reports and some interpretation of company speak and spin. Equally I expect there are important nuggets of information hidden away in the notes that one would be sensible to look at.

His email got me thinking. I rely heavily on annual reports, but Chris is right: they are daunting.

Peter Lynch, summed them up in his book One Up on Wall Street. He wrote:

“It’s no surprise why so many annual reports end up in the garbage can. The text on the glossy pages is the understandable part, and that’s generally useless, and the numbers in the back are incomprehensible, and that’s supposed to be important.”

In fact Lynch was writing over twenty years ago and things have probably got worse as the girth of annual reports has thickened.

Nevertheless the annual report is the only document in which listed companies must give a full account of how they have performed and their financial status. Fully listed companies must also tell us about their business models and strategies, which is how they make money and how they will make more.

So I am going to write the aide memoire, but first a caveat. No company is the same, and no investor is the same, so there is no routine we can follow by the letter.

1. Write down what we know and would like to know

We should have prototypical reasons for wanting to invest in the business, and be gathering prototypical reasons why that might not be a good idea. The purpose of reading the annual report is to confirm or refute these reasons and fill the gaps in our knowledge.

What we write down at the outset is our guide to navigating the annual report. It literally tells us where to look.

I always consult SharePad before taking on the annual report. I focus on profitability, cash flow, and debt, and because SharePad data goes back almost to the dawn of time itself, I will already have a good impression of when the company has done well and when it has not.

This tells me which years annual reports will be most rewarding to read (when the company has performed particularly well or badly), and whether there is any financial information I need to double check in the source.

2. Check the numbers first

Investors often read annual reports from back to the front.

This is not as perverse as it sounds because the back of the annual report contains the numbers. Before we read what the managers say about how well they have done, it is a good idea to have formed our own opinion.

Because I try to keep things simple, I do not read every number. I focus on profit. There are so many ways profit is calculated the directors can be talking about a completely different number to the one we consider to be most relevant.

To decide how much profit a company has made, we need to look at the adjustments it makes to calculate its preferred measure. These are so called “exceptional”, “non-recurring” or “one-off” items sometimes itemised in the profit and loss account and more often relegated to a note.

Exceptional items are identified by management but it is really up to us to decide whether excluding them from profit is justifiable. This is how I judged RM’s profit. RM is an education business and a share I ended up buying.

Of course it may be that a company’s profit is not the most interesting thing about it. My preliminary work in SharePad guided me to look at capital expenditure at Nichols.

When a company is changing shape, using cash flow from a business with limited prospects to build up another which will diversify and grow its revenue, we may need to look more closely at the note containing the Segmental report.

Here, a company will divulge revenue and profit for its main divisions or business units.

For example, Bloomsbury Publishing, famous for its hugely profitable Children’s division and the Harry Potter books, has acquired dozens of Academic and Professional publishers and is welding them together into what could be a highly profitable business.

3. Then check the blurb

Once we have decided how a company is performing we can challenge the directors to tell us why they have done so badly or so well. They should tell us in the “glossy pages” at the front.

The most useful sections of the annual report are often the most mundane. The ones where the regulations hold most sway, and the ones signed by the finance director.

Just like the numbers, these pages are best read back to front. Now we know what we are looking for, we can skip through with a little more alacrity.

The format of AIM company reports is less closely prescribed though, so we may have to dredge details out of the chair’s and chief executive’s statements close to the front of the annual report as well.

From back to front, this is what we can expect:

Auditor’s report

Auditors very rarely qualify their opinion on the financial statements, but it can be useful to note which areas of accounting they focused their investigation on.

Remuneration report

This is where executive pay is disclosed. For fully listed firms the regulations require dozens of pages of disclosures, which is an indication of how ludicrously complex executive pay has become.

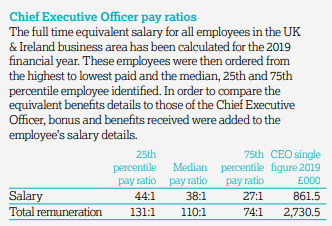

Large firms are required to disclose a comparison of the chief executive’s total remuneration with median levels at the firm though, and this can be a useful indication of how exploitative a company’s culture might be.

When I looked at Bunzl’s financials, I saw something special, but its remuneration report is all too familiar:

Source: Bunzl Annual Report 2019

I think we need to ask questions when the boss earns 110 times as much as the median worker (the relevant line in the table above, as bonuses and benefits are included in the employee pay used in the comparison).

Excessive pay counts against a company in my evaluations. It can mean the board is more interested in filling its own pockets than rewarding employees and shareholders fairly and building a great business.

Bunzl though is a great business in many ways and can afford to enrich its executives. The disproportionality of executive pay is probably more a reflection of our values as a society, which has normalised high levels of inequality.

Principal risks

Only marginally less ponderous than the remuneration report, the section on principal risks is shorter and gets us closer to business matters. Some of the disclosures in this section are boilerplate, pretty much every business has to worry about cyber security for example. But some companies spell out the commercial challenges they face, and also present convincing arguments as to why they might overcome them.

Companies do not like to talk about why they might lose money, which is what makes this section so compelling. It is the only place they have to do it.

Business model and strategy

Having read up on why a company might not make as much money as it hopes, we can flip forward to the next section and read about how the company will address the risks through its business model (how it makes money) and its strategy (how it will make more).

I chose one of my favourite companies, XP Power, to illustrate the connection between how a company makes money, how it might make more, and what could go wrong, because both the Business model and Strategy sections of its annual report and the Principal risks section are exemplary.

Financial review

The chief financial officer will often repeat what the chief executive and chairman say even nearer the front of the annual report, but she will add more commentary on the numbers and how they were derived.

For this reason I read the Financial review quite closely and give myself permission to skim-read what the chairman and chief executive have to say.

Failure is an option

There is no need to beat ourselves up if, having read or skimmed these sections we still do not get it. If a company does not explain itself well it is not our fault, it is theirs.

Fortunately we do not have to understand every company, just a dozen or two in a variety of industries.

Investing is a matter of finding a diverse group of companies we understand with good prospects, and not paying too much for shares in them.

Simple, perhaps, but it is not always going to be easy!

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.