Richard takes a first look at protective packaging distributor Macfarlane, a company so boring even he could not bring himself to investigate it.

The idea of investing in Macfarlane has been sitting with me for a while because an investor I follow has been banging its drum on Twitter. I have ignored him for all sorts of bad reasons.

Bad reasons to ignore good investors

Packaging does not light my fire, and Macfarlane mostly distributes packaging, which is even more boring than manufacturing it. Also my delicate ego likes to believe that every investment starts as well as finishes with me.

A useful rule of thumb in investing is that boring businesses are fertile sources of hidden value. Another is that ego is unhelpful.

Just because someone we know has discovered a business first and put the idea “out there”, does not mean it is a bad idea or that it has become mainstream and worthless. If it is a boring investment, other people are probably ignoring it, like me.

The idea of investing in Macfarlane came from Lewis Robinson, and this tweet links to his write-up. I follow Lewis because he says sensible things, and I trace at least two of my current holdings, companies I admire, back to conversations with him.

There is a danger in writing up an idea already expounded by somebody else, which is that you end up marking their homework. I would not be so bold. We have different styles of investment and different approaches to analysing companies.

So without further reference to Lewis’ write-up, here is mine.

Something to make you sit up and take notice

Macfarlane distributes protective packaging, cardboard boxes, tape, and stuff like bubble wrap that fills the empty space. Protective packaging is used to protect products in storage or transit.

Boxes are a bit more sophisticated than they used to be, but it seems likely that Macfarlane’s competitive advantage does not stem from the uniqueness of the product.

The company says it is the UK’s largest packaging distributor. In 2015, longstanding chief executive Peter Atkinson said Macfarlane was three times the size of its largest competitor, and the only distributor with a nationwide network of warehouses.

Since then, it has grown bigger, mostly by buying smaller rivals. In the year to December 2015, Macfarlane’s turnover was £170 million and in results published last Thursday for the year to December 2021, it reported turnover of £264 million.

Today it has 27 warehouses and four manufacturing sites, where it makes bespoke packaging. Hitherto this has been a very small part of the business but an acquisition in 2021 contributed to a near tripling of manufacturing turnover to 11% of the total.

Roll-up, roll-up, Macfarlane is another roll-up

Rolling-up smaller distributors is often a reliable and low-risk path to growth. I have written about the strategy before. The executive summary is: Local distribution businesses are small, simple, and very similar to the acquirer so they are easy to incorporate.

Once acquired, they add value because the bigger the business is, the more cheaply it can source products and the better it can service customers in different regions. Since the mothership usually has more efficient systems, it can add value to the acquired business by sharing them.

Macfarlane has over 20,000 customers, many of them small businesses, but in 2015 and probably still today, it was the only company able to meet all the needs of customers with nationwide operations.

Its strategy is focused on acquiring businesses and making the most of its scale by focusing on companies that operate nationwide in industries likely to grow: internet retail (like Argos), logistics (like DHL), and life sciences (like Peak Scientific).

It is also reducing the number of smaller warehouses it operates by relocating them to bigger, newer and more efficient sites.

Protective packaging is not a high priority for customers, so straightforward though it may seem, they need advice. Macfarlane says it adds value by helping customers appreciate the total cost of packaging in terms of optimising warehousing and transportation, reducing their carbon footprint, understanding the impact of damages and returns, and helping with efficiency and automation.

How good is Macfarlane?

The company published full-year results last Thursday and the highlights are encouraging. It grew turnover by 26% and operating profit by 47%, helped significantly by two acquisitions and more business from some of its industrial customers as the impact of the pandemic receded.

At the year end in December 2021 Macfarlane had more cash than bank borrowings, and its pension fund had swung from a funding deficit to a funding surplus.

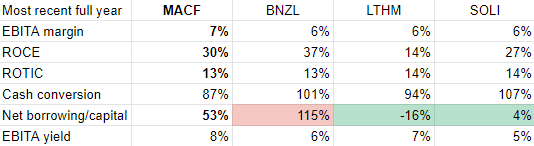

I have made a comparison with three distributors I know well.

The four distributors in my comparison are Macfarlane (MACF), Bunzl (BNZL) a multinational distributor of consumables used by companies, hospitals and other large organisations, James Latham (LTHM), an importer and distributor of timber products, and Solid State (SOLI) a distributor of electronic components.

You can read about Bunzl and James Latham in my previous write-ups.

Here is how they compare, judging by their latest full-year results:

Source: Calculated from data in SharePad and annual reports

EBITA is Earnings Before Interest, Tax and the Amortisation of acquired intangible assets, and it is the return or profit figure used in all of the calculations.

To explain why I exclude the amortisation of acquired intangible assets, consider Macfarlane.

The company identifies two kinds of acquired intangible assets, brands and customer lists, and it is required to amortise (reduce) their value over time even though there is no reason to believe they are actually depreciating in value. If the company is doing its job properly, they should be appreciating.

Accounting rules do not allow for the amortisation of brands the company develops or customers it recruits itself, so I think adding back these accounting figments gives a more accurate impression of the company’s profitability, and brings the figures in line with businesses like James Latham that have relied much less heavily on acquisitions.

In terms of profit (EBITA) margin there is very little to choose between these businesses despite the fact they distribute wildly different things.

All four businesses generate high returns (also in terms of EBITA) from their tangible capital. This tells us the businesses efficiently convert stock, warehouses and vehicles into profit, enabling them to pay shareholders dividends and invest the surplus to grow.

ROTIC is Return on Total Invested Capital which compares profit (EBITA) to capital including goodwill and amortisation at cost. These businesses have all been good acquirers because they earn decent returns on the total cost of their investment.

In terms of financial obligations, there is a wide spread. Bunzl and Macfarlane lease much of their property and equipment, while Solid State and James Latham tend to buy it outright without much recourse to borrowing, which makes them more conservatively financed.

Bunzl and Macfarlane are reliable earners, though, and their ability to pay the rent has not come into question, at least in the last ten years.

None of these distributors look egregiously expensive when we compare profit (EBITA) to market value (Enterprise Value). Macfarlane looks cheap. It returned about 8% of the debt and equity in the business in 2021, equivalent to a multiple of about 13 times EBITA.

On the basis of their most recent financial years, Macfarlane does not look out of place in this group I have already deemed worthy of investment!

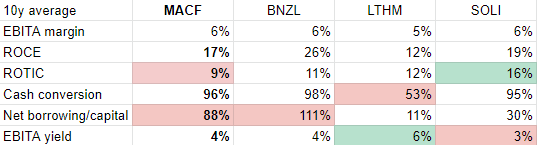

This is how the 10 year averages compare.

Source: Calculated from data in SharePad and annual reports

All of the companies look a little less attractive, which may just demonstrate that distributors become more efficient as they grow. But Macfarlane’s recent performance is more exceptional compared to its more distant past than the others. That is, of course, another way of saying it is doing much better than it was.

If 2021 had been typical of the last ten years, Macfarlane would have earned a return on capital of 17% compared to 30% in the year to December 2021, and most of its tangible capital would have been financed by financial obligations (leases, bank debt and pension deficit).

The return in terms of profit or EBITA it would have earned investors on that capital, would have only been 4% of its current enterprise value, a rather more expensive multiple of about 25 times profit.

Will the real Macfarlane stand up

The challenge facing long-term investors is deciding how Macfarlane will perform in future. Will it maintain the turbocharged performance of recent years, which makes the shares look like a bargain at the current price? Or will it be the average of its past performance, a good business trading at quite a high price?

I am in two minds. I think of distributors as stable businesses that grow better slowly over time and I am a bit sceptical when I suddenly see one taking performance to a new level. The company has experienced a boom because of the movement of retail online and the allied boom in logistics, which was accelerated by the pandemic. Will this endure? Or will it normalise?

The conventional wisdom is some of it will stick, and Macfarlane has other opportunities to grow. It is following its customers into Europe in partnership with overseas distributors, and it has perhaps taken a first step in scaling up the manufacturing side of the business. That will give it the opportunity to differentiate products and distribute them through its national network.

These developments may even make Macfarlane a more “interesting” business!

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

I too got this idea from Lewis and am very grateful. I have no shame at all about copying others’ ideas but rarely do as most write-ups are sales pitches.

I would add that the business is very well run. Understated management that eke out operational improvements year in year out focusing on the right KPIs like on time in full, stock turn etc.

Regarding your numbers, I come out with a higher EBITA margin for 2021 at closer to 9%. I add back amortisation of acquisition intangibles as you have, subtract lease interest, but also normalise for full year Carters/GWP earnings (see note 9 to accounts) – that gets it to 8.6%. There is then a £1.9m dilapidation provision taken to the P/L relating to a site consolidation – there may be further such occasional provisions in years to come but not every year so this is not entirely a recurring cost. Also not every site consolidation they do will incur these.

Thanks for your fascinating reply Jerry. The idea of treating acquisitions as though they have been owned all year had not occurred to me probably because I do not put much emphasis on a company’s annual performance. If the acquisitions have a long-term impact on margins and ROCE then it will come out next year and thereafter though I appreciate there is a time lag and I can absolutely see that if you are gleaning insights about future levels of profitability from the current year this makes sense. On dilapidation provisions I think I agree with the arguments you and Lewis make for treating them as exceptional items. Because I am quite systematic I would have to make the adjustment for all the companies I follow, which would be quite a commitment and again I would have to make a call on whether it is worth the effort. Obviously I long ago decided it is in respect of adjusting for acquisitions, so perhaps I should,,,

Hi Richard

I think their conservative accounting is very refreshing, though ideally I’d like to see these dilapidation provisions capitalised well in advance and amortised in order to smooth out the effect, as I do think they are lumpy, but I suspect there are sensitivities in consolidating sites such that decisions are not formalised too far in advance. I have arbitrarily added back 50% of the current year’s provision in citing the 9% pro forma margin.

It’s hard to be precise, but with Buffett’s aphorism in mind about not needing scales to know someone is overweight, this is a great business at a 10-11 p/e with downside protection from the conservative balance sheet, conservative management team and through-the-cycle stability. And as a fellow student of Mandelbrot, I think markets are more treacherous places than commonly understood so I like my (few but large) positions to be unbreakable.

Cheers, Jerry