I found James Latham a couple of months ago when I was trawling for cheap shares with strong balance sheets.

The shares are still cheap, James Latham’s Price Earnings (PE) ratio is 13, and the balance sheet should remain strong…

Centuries trading timber

James Latham has a long and storied history. It manufactured plywood for Mosquito aircraft during the Second World War, joined the stockmarket in 1965, and became the first signatory of the Timber Trade Federation’s Responsible Purchasing Policy in 2001. Source: James Latham History Roll

The company supplies joiners, manufacturers, shopfitters, and timber merchants with wood, mostly, and a bit of plastic.

It sells commodity products like Medium Density Fibreboard (MDF) and plywood, high grade softwoods and more exotic hardwoods, melamine and laminate panelling, decorative mouldings, door blanks, and branded engineered timber like its exclusive WoodEx brand.

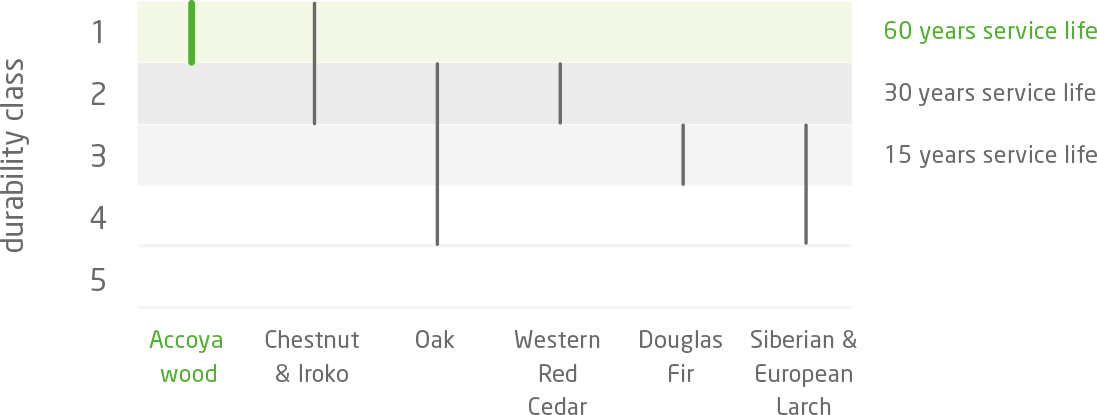

Harvested from fast growing trees, Accoya, which is not exclusive to Lathams, is as durable as tropical hardwoods due to the way it has been treated. Source: lathams-accoyacladding.co.uk

Engineered woods are laminated and free of imperfections like knots, making them stronger and more versatile than regular timber. Because they are made from many pieces of wood, they are also less wasteful and easier to work with.

A promotional video for architects and other specifiers shows how James Latham products can make offices, schools, hospitals and shops safer. Source: lathamtimber.co.uk

Trading seems to have been largely unaffected by Covid 19 in the year to March 2020 so we are looking back with rose-tinted spectacles.

Revenue, not including the revenue from a small acquisition, and profit were pretty flat. The year, the company says, was marked by low customer confidence and delayed investment due to Brexit.

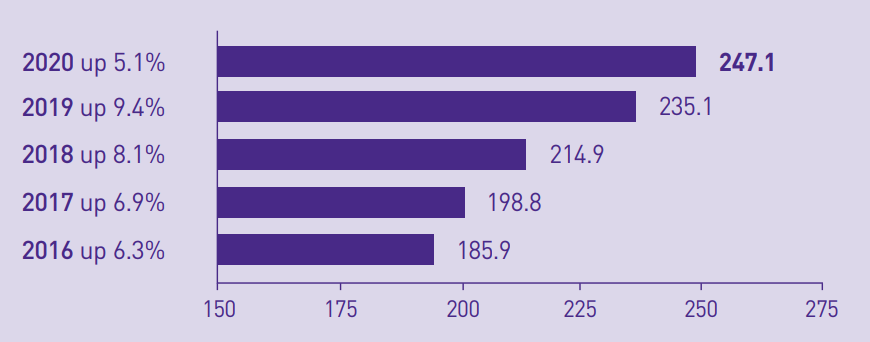

Including a small acquisition, revenue rose 5% in 2020. Be wary of charts that do not start at zero. The scale on this chart starts at 150 (million), which makes the jumps between years look bigger. Source: Annual Report 2020.

During Lockdown, James Latham kept most of the 13 depots from which it serves the UK and Ireland open to support the NHS and other customers still doing business. But it delayed shipments of new stock and took advantage of the furlough scheme where it could.

April Sales were 40% of the previous April, recovering to 80% by June.

The company has not predicted the outcome for the current year, which will be impacted by the ongoing pandemic, but it is paying a final dividend, albeit reduced from 12.9p in 2019 to 10p, which probably shows some confidence in its ability to survive and prosper.

Chairman Nick Latham believes it is strong enough to avoid the worst of any downturn. Perhaps we can discover why, by looking at the company’s performance through thick and thin.

Recession risk

James Latham supplies firms working in the construction and retail industries, which experience swings in demand related to the strength of the economy.

However, it seems likely (the company does not provide figures) that there is a reasonable spread between public and private sector and commercial and residential construction.

Since each market tends to follow its own cycle, James Latham may not experience as drastic swings in demand as some of its customers.

James Latham serves a variety of cyclical markets. Source: Annual Report 2020

Looking back to imagine the future

No two recessions are the same, but if James Latham performed adequately during the Great Financial Crisis, it may give us some confidence.

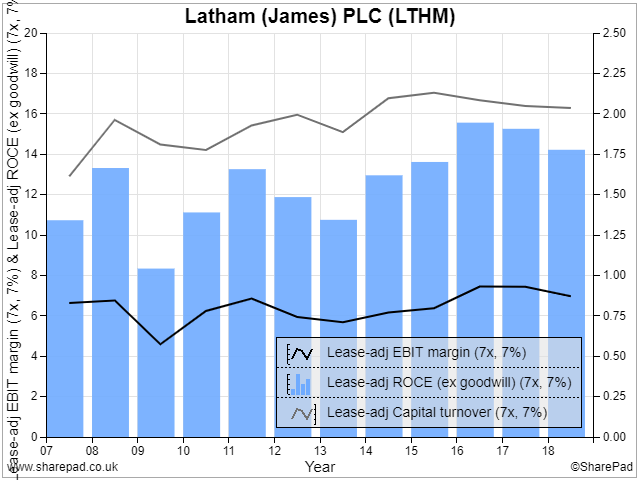

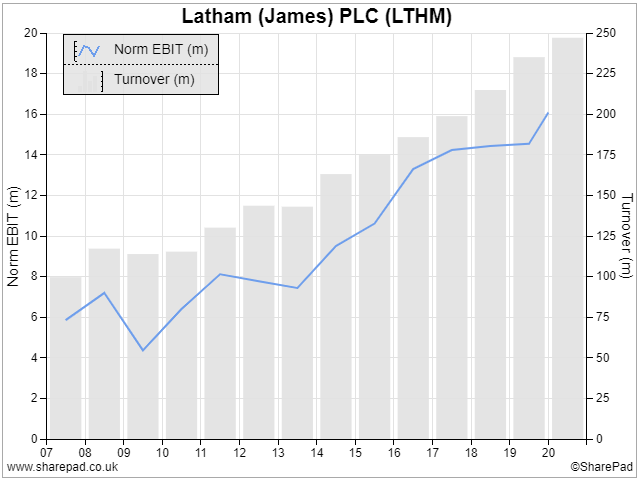

It did. Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) was 8% in 2009, its lowest year. Then, the company reported a small decline in revenue, but Earnings Before Interest and Tax (EBIT) declined by 39% from £7.2 to £4.4m according to SharePad’s normalised data:

It is slightly alarming that profit should fall so much when revenue fell so little.

The previous year had been an exceptionally profitable one, when demand was high and the company had been able to earn higher profit margins. Lower demand coincided with a fall in sterling against the euro and the dollar, increasing cost prices and further squeezing margins. The company also had to bear the cost of a new depot in Motherwell, Scotland.

Encouragingly, James Latham says it has improved the product mix, selling more high value products like branded panelling and engineered wood. The reduced share of commodities like MDF and raw timber, may mean healthier profit margins even during recessions.

Since that exceptionally good year in 2008, James Latham has more than doubled revenue and profit, and profitability in terms of ROCE has improved somewhat, probably because the company is bigger and more efficient and maybe because the sales mix contains more unique or at least premium products.

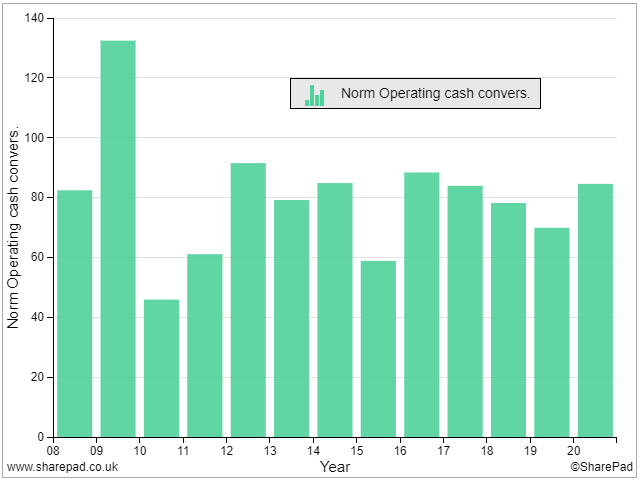

But cash flow is mildly disappointing:

Operating cash conversion is invariably lower than 100%. This is primarily due to investment in working capital. The company holds a lot of stock, which must increase ahead of growth, and customers (aka debtors) take a long time (upwards of 50 days) to pay for timber they’ve received.

According to the principles of accounting, companies recognise costs and revenue when they make a sale, so unsold stock at the financial year end is not yet counted as a cost and does not depress profit. Invoiced sales yet to be paid are recognised as revenue and do therefore contribute to profit.

Most of the stock, still in the warehouse or shipped and awaiting payment, will have been paid for by James Latham though, which explains the discrepancy between cash flow and profit.

When James Latham slams on the breaks, as we saw during the GFC and in the early days of the pandemic, the company defers purchases but continues collecting payments, and cash flow is greater than profit.

In 2009, when the company put on the brakes to conserve cash, it made more money in cash terms than in profit (operating cash conversion was 130%).

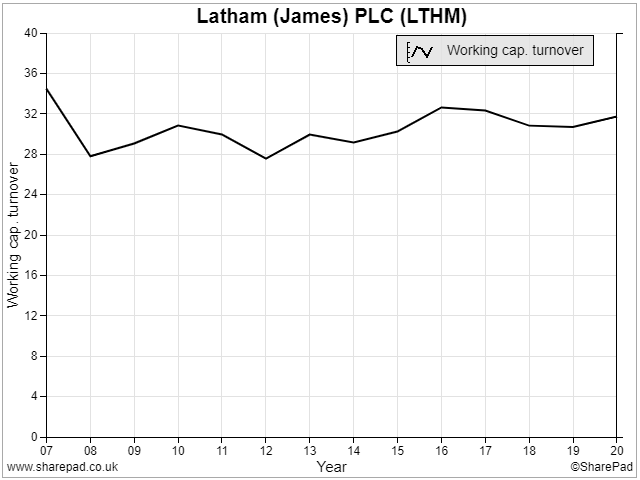

The important thing is that its working capital requirement is not increasing as a proportion of turnover over time. In fact it is remarkably consistent. The fractional rise in recent years is probably due to overstocking to ensure supply after the postponed Brexit deadlines, when trade was widely expected to be disrupted.

There is a risk during recessions that customers will not be able to pay because they have gone bust. The company did experience an increase in bad debt in 2009, but it was contained and did not seriously dent cash flow.

Another source of reduced cash flow is the pension fund, although here too, the risk is manageable. The deficit, the difference between the value of the pension fund’s assets and the size of its obligation (an estimate of how big it needs to be to meet future pension payments), is about £12m.

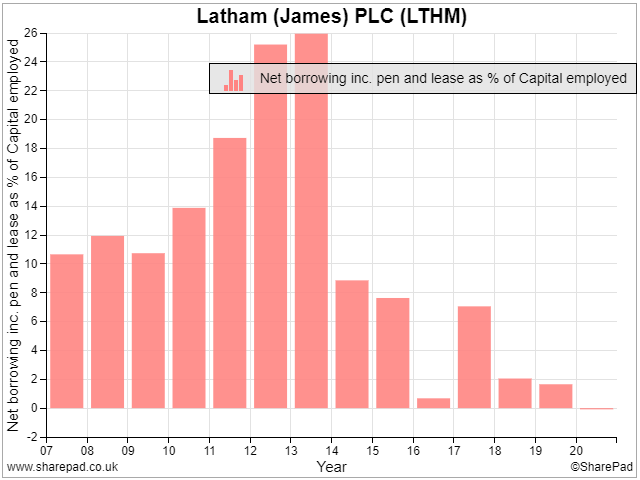

This ‘debt’ is not troubling because the company’s other financial obligations are not onerous. It has no borrowings and minimal lease obligations. In fact James Latham had roughly enough cash at the year end to pay off its pension deficit and lease obligations:

The problem with pension deficits is they are highly sensitive to movements in the value of the fund’s investments and the calculations of actuaries who estimate the size of the obligation.

The bigger the obligation, the greater the risk that the deficit might yawn wide open.

Investors compare the obligation to various figures to determine the risk. I get nervous if a company’s pension obligation is greater than the capital required to operate the business (capital employed).

James Latham’s obligation is £70m, little more than 60% of capital employed.

The numbers are those of a well managed business and the current executive board was responsible for them:

| Name | Position | Years at company | Years on board |

| Nick Latham | Chairman | 28 | 13 |

| David Dunmow | Finance director | 26 | 20 |

| Andrew Wright | Managing director | 19 | 5 |

| Piers Latham | Executive director | 27 | 6 |

Executive directors at James Latham. Source: Annual Report 2020

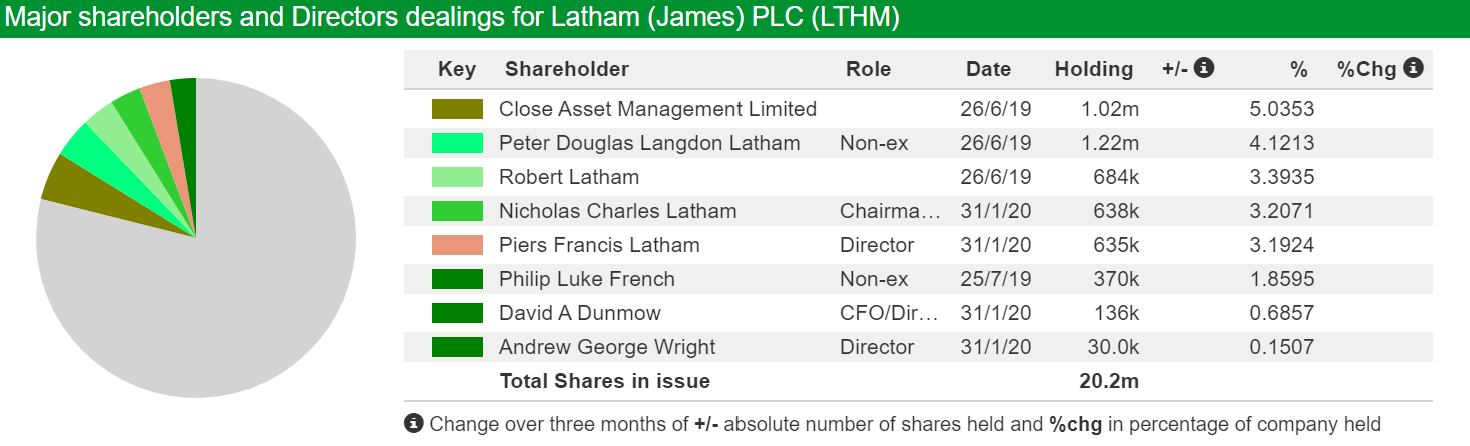

They are also major shareholders:

Source: SharePad

The story behind the numbers

I like the idea of investing in James Latham.

The company’s ethos is long-term. It gives site directors the autonomy to determine their own sales and purchasing strategies, a strategy that works very well at Howden Joinery (it manufactures kitchens).

It looks after its staff. Furloughed staff earning under £25k were paid in full, and it bettered the government scheme for the rest.

Trained and motivated employees look after customers. Two of the company’s six key performance indicators are there to drive down the time it takes to turn around an order.

James Latham’s large holdings of stock, which dents cashflow, are there to ensure customers get the right material at the right time. Around Brexit deadlines it worked 24/5 to make sure it was fully stocked.

The company claims to be well respected for its principled trading policies and integrity. All but 3% of the wood it sells is certified legal and sustainable.

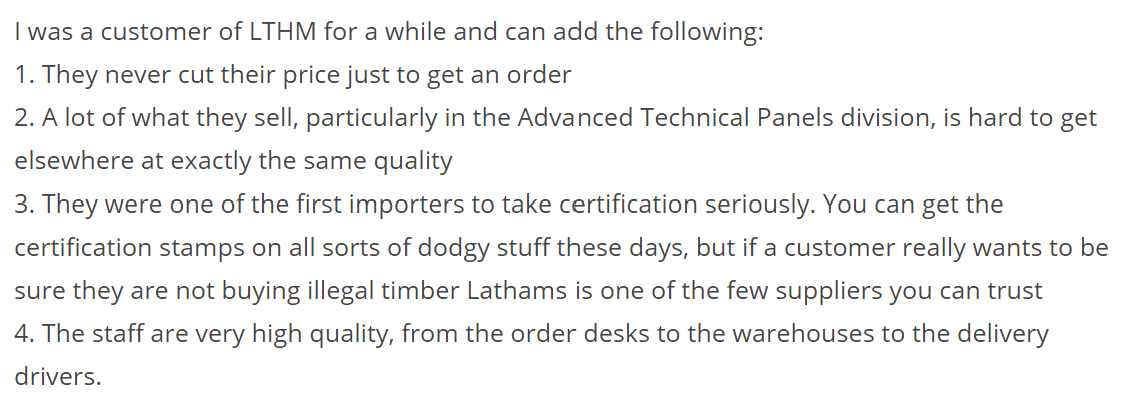

It is anecdotal evidence, and only one person’s experience, but this comment on a write up on SharePad writer Maynard Paton’s website, chimes.

Source: Michael, from a comment on Maynard Paton’s website in 2018.

The future

As for the future, the company wants to expand the product range, including more third party products like the big laminate brands it already stocks. It wants to improve service levels and its on-line-trading platform.

Shareholders may have to get used to acquisitions too. So far, though, it has been very tentative and their cost and returns are immaterial.

Dresser Mouldings, purchased in October last year for just £1m (including cash on the balance sheet), looks like a decent adjunct to the business though:

Dresser Mouldings makes skirting, architraves, cornices, panelling, cladding, handrails, stair components and carvings. Source: dressermouldings.com

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.