Bruce looks at UK banks’ FY Dec 2021 results and draws out some themes on revenue, profitability, “one off items”, competition, interest rates and price / book valuation.

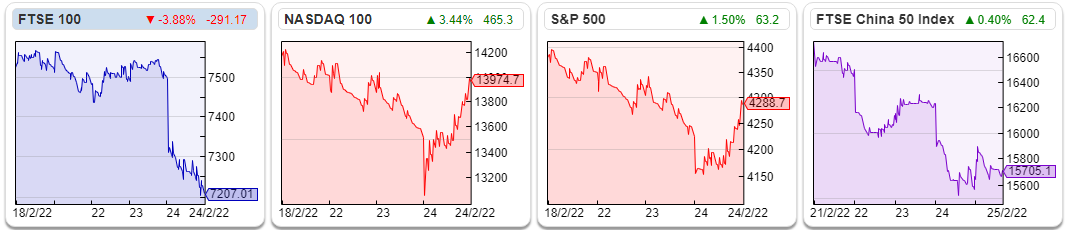

The FTSE 100 sold off sharply last week down -4% on Thursday last week. US markets were more sanguine with the S&P500 down -1.4% and the Nasdaq100 down just -0.3%. Brent Crude rose above $100 per barrel, but then fell back to $97. The US Government bond yield remained at 1.99%.

The news agenda was dominated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Bad luck to Ferrexpo (Ukrainian Iron Ore) and Evraz (Russian steel) holders down -42% and -30% last Thursday. BGEO and CGEO were also off around -10%; short term that makes no sense. Putin is unlikely to invade Georgia if he’s committed hundreds of thousands of troops to Ukraine. Longer term, there is some risk, for instance the ruling Georgian Dream political party, founded by Bidzina Ivanishvili, could become less friendly to international investors. Ivanishvili is an interesting character, having made billions in Russia in the late 1990s and early 2000s and presumably still has connections with Russia. Plus BGEO has a small subsidiary in Minsk. Longer term consequences for the markets are much harder to interpret. In the face of the uncertainty gold is $1,904 up less than +5% since the start of the year.

Last week we saw a possible offer worth 920p for Clipper Logistics. Jamie wrote about Clipper a couple of weeks ago here, noting that they were the distributor for Joules. This looks like a generous bid, as Clipper seems to be able to capture the value from their distribution relationship with Joules, and I’m not sure how sustainable that is longer term. That follows Wheels Up, another US company’s bid for Air Partner a couple of weeks ago. Theoretically events in Ukraine should not put off overseas corporate buyers looking for cheap valuations in London, but in practice Chief Executives probably will be more cautious.

This week my commentary has a different look. I’ve decided to focus on one sector: UK banks, and draw together themes by revenue, profitability, competition, valuation etc. All the large banks reported last week or the week before. Between 2000 and 2013 I used to pay close attention to their results as a UK banks’ equity research analyst. Banks have been such poor investments but perhaps with rebounding economies and rising interest rates their time in the sun has come. That said, we’ve seen so many false dawns before, I don’t think banks shares should be a high conviction trade for any investor.

First an explanation why Price to Tangible Book and Return on Tangible Equity (RoTE) is used to value banks, but rarely for companies in other sectors.

Price to book Normally when investors discount dividends back from the future, they use the cost of equity (roughly 9%) as the discount rate. The lower the discount rate, the higher the future value of the cashflows. Cashflows from bonds and equities are not quite the same though, because bonds pay out their contractual coupon whereas with equities some (or all) of the cash is reinvested to grow the business. So the future value of equity, is discounted at the cost of equity less reinvestment at the assumed future growth rate (CoE – G) the denominator in valuation equations. Mathematically the lower the denominator, the higher the value, so higher growth is good. That agrees with common sense.

![]()

For example a company paying a dividend of 5p per share, valued with a 9% discount rate is worth 55p per share. But if we deduct from the discount rate a perpetual 3% growth rate to give a 6% denominator in the fraction, then the target price rises to 83p per share.

A slightly more sophisticated approach is to substitute DPS in the numerator for Return on Equity less the growth rate to give a target Price to Book multiple. Dividends are profits less the capital held back to reinvest and grow the business. So that equation has the advantage of explicitly including growth in both the numerator and denominator, and rewarding companies with high returns and high growth.

![]()

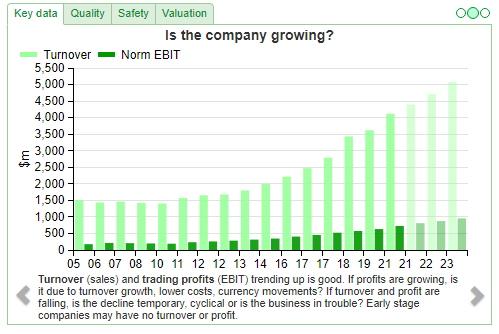

For some sectors investors have realised that tangible accounting book values aren’t particularly useful, because modern accounting fails to capture the value of network effects, brand or human expertise. O’Shaugnessy Asset Management (OSAM) wrote this up a couple of years ago, giving the example of the US Domino’s Pizza Inc which IPO’ed in 2004 with negative tangible book value, but has increased in value around 30x since then. Lacking tangible equity has not prevented Domino’s Inc from growing revenue and EBIT, as the chart on the next page shows. Other flaws in this valuation approach are that it doesn’t adjust for leverage and that it assumes that capital can be reinvested at the historic RoE. The last assumption is highly dubious for a company like McDonalds, where OSAM point out that much valuable property has been depreciated off the restaurant company’s balance sheet, therefore reducing book value.

Despite these limitations banks’ analysts still tend to use price to tangible book multiples, partly because there aren’t many other satisfactory approaches. Currently UK banks are trading on discounts to book, which suggests that investors believe that they will fail to sustain RoE above 10%, despite management having published that 10% figure or greater RoE as their medium term targets.

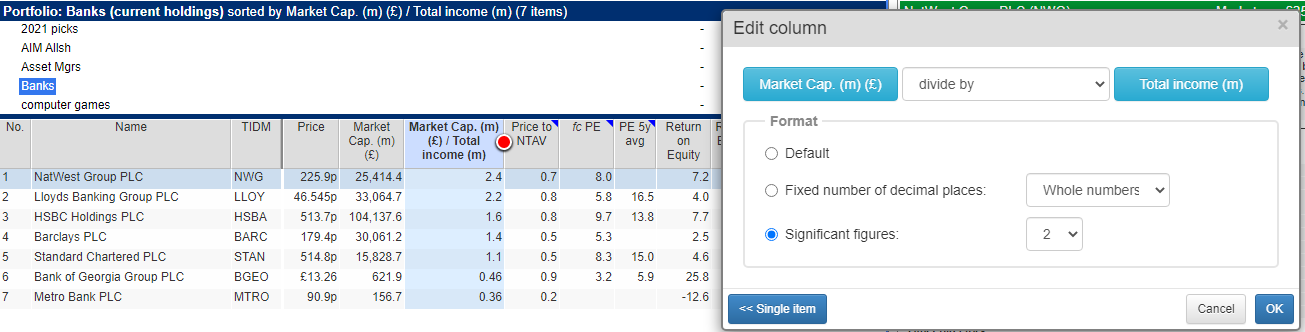

Sharepad has useful features, for instance you can compare Price/Tangible Book ratios, but also using the “combine items” create a Market Cap/Revenue comparison.

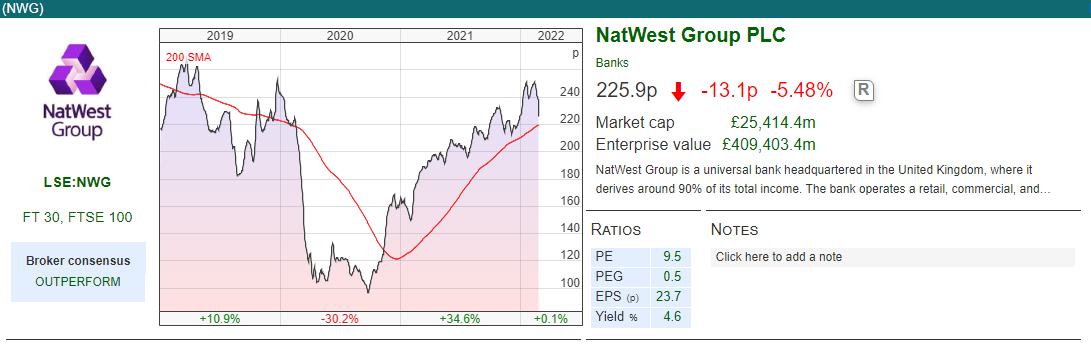

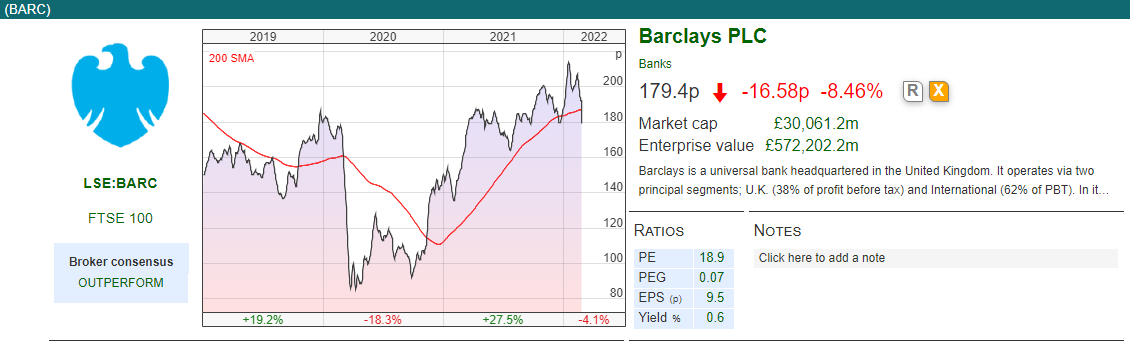

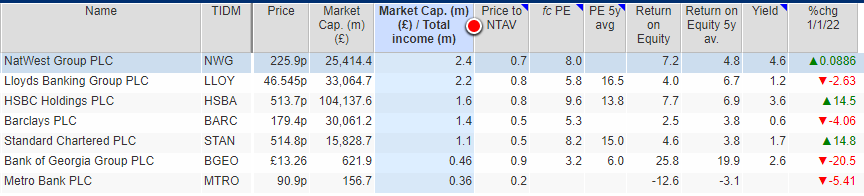

The two ratios tell different stories, with NatWest trading on 0.7x tangible book but 2.4x revenue. At the other end of the table Bank of Georgia trades on 0.9x tangible book but less than 0.5x revenue. My interpretation is that investors are questioning whether NatWest, Barclays and Standard Chartered can sustain their 10% plus RoE targets. BGEO on the other hand looks cheap on both measures, but particularly so on price/revenue. This is partly explained by BGEO’s much higher Net Interest Margins of c. 5% versus half that level for UK domestic banks and even less for the Asian banks (STAN and HSBC). Metro Bank is trading on an even greater discount, but given that the bank hasn’t reported a profit since 2018, that discount may be justified.

UK Banks

Revenue Unlike most companies UK banks’ revenue has been shrinking over many years. Sharepad shows that NatWest’s revenue has shrunk by 56% from £23bn in 2011 to £10bn FY 2021.

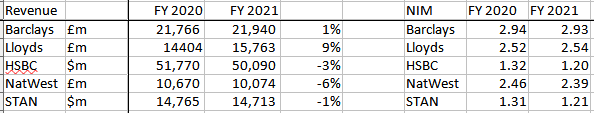

NatWest “Go Forward” revenue, actually went backwards by 6% in 2021. As inflation is currently around 5%, the “real” (ie adjusted for inflation) decline in revenues has been even greater (more than 10% real decline for NatWest and c. 7% for HSBC and STAN). Barclays reported revenue growth +1% to £22bn – helped by the old Lehman Brothers business that they bought at the height of the financial crisis. Lloyds was the only large bank to report above inflation revenue growth +9% to £15.8bn. Lloyds revenue has benefited from a lower charge for operating lease depreciation (£460m v £884m FY 2020) due to higher prices for second hand cars which has benefited their Lex Autolease Vehicle subsidiary (fleet size c. 320K vehicles). Without Lex, Lloyds revenue growth would still have been +6%.

NatWest “Go Forward” revenue, actually went backwards by 6% in 2021. As inflation is currently around 5%, the “real” (ie adjusted for inflation) decline in revenues has been even greater (more than 10% real decline for NatWest and c. 7% for HSBC and STAN). Barclays reported revenue growth +1% to £22bn – helped by the old Lehman Brothers business that they bought at the height of the financial crisis. Lloyds was the only large bank to report above inflation revenue growth +9% to £15.8bn. Lloyds revenue has benefited from a lower charge for operating lease depreciation (£460m v £884m FY 2020) due to higher prices for second hand cars which has benefited their Lex Autolease Vehicle subsidiary (fleet size c. 320K vehicles). Without Lex, Lloyds revenue growth would still have been +6%.

The table below compares banks revenue growth and Net Interest Margins in FY 2020 and 2021.

Ultra low interest rates have harmed banks, because they are unable to benefit from the funding advantage of having cheap customer deposits. Management are guiding higher Net Interest Margins, so as interest rates rise, don’t expect to see banks immediately raise rates on your savings deposits. They all include disclosure in their Annual Reports which estimate that a 100bp increase in interest rates across the yield curve (ie Central Bank rates rising, but also the long end of the yield curve rising in parallel) ought to increase their revenue by c. 10%.

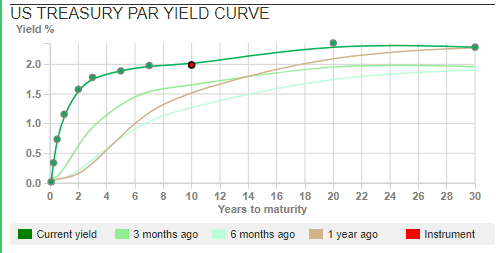

That illustrative sensitivity assumption may be too optimistic though, because Sharepad’s yield curve chart on the next page shows that the short end of the yield curve (which Central Banks control directly by announcing changes to interest rates) has moved much more than the 10 year end of the yield curve.

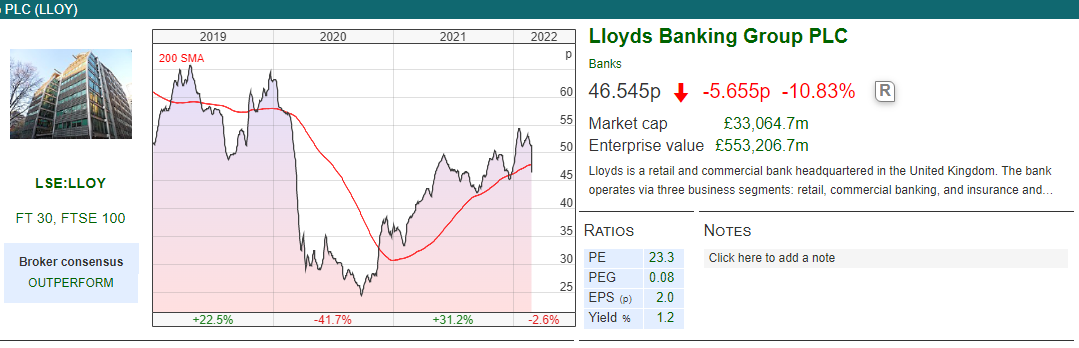

There’s also a risk that as interest rates rise, credit risk increases. In the past the relationship has tended to be indirect though. During the early 1990’s, the 2001-3 recession and the 2008 financial crisis unemployment was a bigger driver of bad debts than interest rates. Given Lloyd’s higher loans/deposit ratio of 94% and high exposure to the UK mortgage market, if UK unemployment does become a problem LLOY are likely to be the bank with the most sensitivity, in my opinion. Most UK mortgages are now on 2-5 year fixes, so problems won’t show up immediately but I think that’s worth investors keeping in the back of their minds.

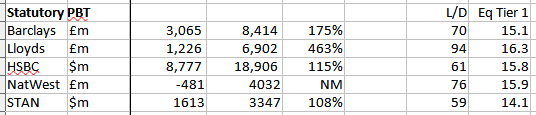

Profits Though bank profits have been in long term decline, in 2021 they recovered. This was driven by much lower bad debts versus 2020, as banks took large “kitchen sink” provisions at the start of the pandemic. As government support measures helped businesses stay solvent, banks profits recovered strongly in 2021. Hence statutory PBT was up 6x at Lloyds and recovered from a loss at at NatWest. As the table below shows, the bank with the highest loans to deposit ratio (Lloyds) appeared more geared into provisions releases.

Profits Though bank profits have been in long term decline, in 2021 they recovered. This was driven by much lower bad debts versus 2020, as banks took large “kitchen sink” provisions at the start of the pandemic. As government support measures helped businesses stay solvent, banks profits recovered strongly in 2021. Hence statutory PBT was up 6x at Lloyds and recovered from a loss at at NatWest. As the table below shows, the bank with the highest loans to deposit ratio (Lloyds) appeared more geared into provisions releases.

Despite shrinking revenue NatWest’s Return on Tangible Equity (RoTE) was 9.4%, benefiting from a £1.3 billion net impairment release.

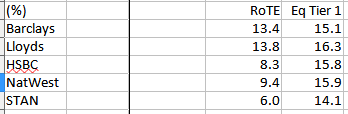

All banks have RoTE targets of above 10% and the outlook statements sound more confident that these can be achieved (for instance HSBC saying that they expect to be there in FY 2023F, a year earlier than they previously expected). Barclays and Lloyds were the only banks to exceed their targets reporting 13.4% and 13.8% RoTE respectively. This was helped by each bank’s revenue performance but also a £0.7bn impairment release for Barclays and a £1.7bn release for Lloyds.

One off items

Banks try to argue that they incur costs that are “one off” in nature, and shouldn’t be treated as a cost of doing business. The fact that 15 years after the financial crisis banks are still paying fines to regulators suggests to me that the costs are ongoing. NatWest paid £466m of conduct costs for FY Dec 2021, including £265m for money laundering for a Bradford jeweller which deposited £260m in cash, some in bin bags with a “musty smell.”

Often regulators find that the burden of proof for a criminal case is too high, and therefore fine management. However, in reality the fines are not effective at changing behaviour, as their regularity shows. Shareholders end up paying the price. The example of NatWest (majority owned by the UK Government) being fined by the FCA (an arm of the UK Government) shows how ridiculous the whole situation has become.

HSBC used to present it’s statutory results without adjustments, saying that as a large global bank, it was hard to define what constituted a significant item that distorted year on year comparisons.

More recently they reported “alternative performance measures”, with various adjustments (for instance Argentinian hyperinflation). I think that their previous attitude towards adjustments had some merit.

More recently they reported “alternative performance measures”, with various adjustments (for instance Argentinian hyperinflation). I think that their previous attitude towards adjustments had some merit.

Buybacks Banks are now reporting excess capital, on the regulator’s preferred measure “core” Tangible Equity / Risk Weighted Assets. Hence last week they all announced increased dividends and share buybacks. NatWest announced a £750m, Barclays £1bn and Lloyds a £2bn buyback. The Asian banks (STAN and HSBC) which are reporting lower returns and trading on lower Price to Tangible Book multiples announced $750m and $1bn buybacks respectively.

Competition Barclays new Chief Executive, C. S. Venkatakrishnan, makes reference to competition from more lightly regulated technology firms. Slide 7 of their analyst presentation shows that even before the pandemic branch visits were declining, and are now down by 2/3 since 2018. Over the same period active customers on their mobile app is up by +33%. This means that competition is coming from a new direction. In July last year Revolut raised $800m in a funding round lead by SoftBank and Tiger Global, valuing the loss making foreign exchange app at $33bn (£24bn).

That Revolut implied valuation is similar to NatWest’s market cap. Other app based banks without expensive branch networks are Atom, Starling and Monzo. Starling’s most recent funding round was March 2021 (£272m valuing it at £1.1 billion pre-money) and Monzo’s most recent funding round was December last year ($1bn valuing the company at $4.5bn). Last week Atom announced that they’d raised £75m at an implied valuation of £435m.

One new entrant that has not been a success is Metro Bank which is trading on 0.2x tangible book, reflecting the uncertainty of the bank’s strategy, that has been loss making since 2018. MTRO reported a statutory loss FY Dec 2021 was £245m, which is larger than the bank’s market cap of less than £160m. Though it is easy to make jokes about Metro Bank, in banking you are only as smart as your dumbest competitor – if a Northern Rock or a Metro Bank is prepared to grow aggressively that can set the marginal pricing of loans, and ruin the economics of better run banks.

Valuation UK banks are trading on discounts to tangible book value of between 0.9-0.5x, ex loss making Metro Bank which is on 0.2x.

Opinion The whole UK banks sector tends to trade in a homogenous way, reflecting concerns over macro economics, interest rates, credit quality and of course, geo-politics etc. If investors do want to buy banks because they think the sector will rise, it tends to be the riskiest banks that rise fastest from their discounted valuations. That would imply a speculative investment in MTRO. That is above my risk tolerance though – banks’ leveraged balance sheets mean that it is very hard to price a “worst case scenario” as the experience of 2008 shows.

Opinion The whole UK banks sector tends to trade in a homogenous way, reflecting concerns over macro economics, interest rates, credit quality and of course, geo-politics etc. If investors do want to buy banks because they think the sector will rise, it tends to be the riskiest banks that rise fastest from their discounted valuations. That would imply a speculative investment in MTRO. That is above my risk tolerance though – banks’ leveraged balance sheets mean that it is very hard to price a “worst case scenario” as the experience of 2008 shows.

Despite the £2bn buyback and attractive valuation I’m cautious on Lloyds because of the UK housing market, and I think Barclays may struggle to sustain performance in their investment bank, given how favourable market conditions have been over the last 18 months. That leaves STAN and NatWest as potential trading buys, while I hope my long term investment in BGEO which I’ve held for a decade eventually rewards me.

Bruce Packard

Notes

The author owns shares in BGEO

This post is very simple to read and appreciate without leaving any details out. Great work!

online casino games real money