Jamie Ward takes a detailed walk through two expansion strategies and outlines the types of company and sectors where investors are likely to find these strategies as well as highlighting how to spot companies using them well.

Two common ways for profitable growth for many companies can be summarised as roll-out and roll-up. Roll-out is fairly simple and can be very profitable for a while. The key is to determine when the story is over.

Roll-out

Roll-out means a simple expansion strategy of a proven business model. It can occur in a number of sectors but is most common in consumer facing businesses, especially with a high street presence. There is a fairly well trodden path that runs roughly as follows:

- Start: an entrepreneur has an idea or, more importantly, the grit and determination to see an idea through to some degree of success. The truly exceptional then can move on to expansion. This stage is about using the lessons learned in the initial start up to add capacity. As someone who has never done this, I’d imagine this is far easier said than done.

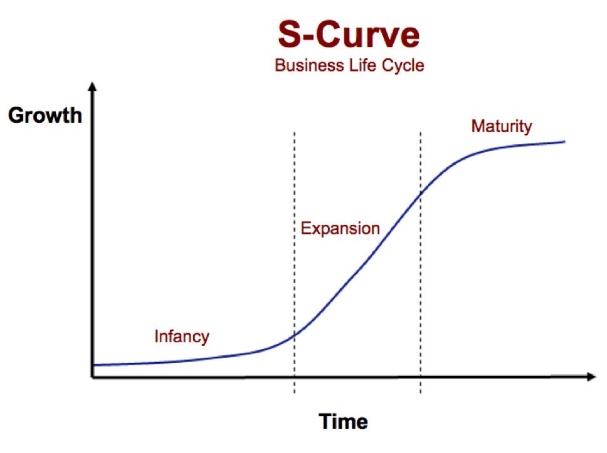

- List: once the business is of a sufficient size and expansion has become (somewhat) routine, a company may be listed. This can be for a few reasons but largely boils down to access to capital. Often this stage represents an acceleration as the management team have both the expertise to build out and the capital to do so. As an aside, investors are often carried away by the profitable growth displayed and extrapolate beyond what is feasible. Ultimately, company expansion sits on an S-curve not an exponential curve and so one eye must be kept on the how large a business can become.

- Maturity: this is a much trickier period and occurs as the S-curve begins to flatten. It is rare that a business simply stops growing. Sometimes managers are able to extract greater value through evolution; through finding new ways of expansion; or by transitioning into cash generators content at size but then it is no longer a roll-out business. Often however, growth continues unabated in a manner that destroys value in the business.

The second bullet point ‘List’ until maturity represents the roll-out phase of the strategy and is the opportunity that investors should be looking for. Below are a few examples of businesses and sectors that have followed this path at various points in the lifecycle:

- Supermarket groups; in the early days, supermarkets generated profitable growth because there had always less efficient competition. This was through both absolute scale, as larger stores rendered the Arkwrights of the world unprofitable, and scope with supermarkets placing a greater and greater of variety under one roof. However, whilst profitable growth continued after c. 1990, the sector has been a victim of a quasi-prisoner’s dilemma for since then where an agreement by all parties to cease expansion would yield benefits for all. That is to say, at a sector level, returns on capital have been in decline; this was hidden somewhat in the share price performances because the cost of capital has also been in decline shielding poorer returns with lower costs. The sector has been a dog for while now and it is difficult to see it ever been anything else as, whilst there is clearly enough capital in British food retail at this point, new capital keeps coming to address greater convenience (internet) and underserved segments (Aldi et al). The effect is cannibalisation of existing supermarket returns from growth for its own sake – growth without control is cancer. Below is the long-term log chart of Sainsbury since 1994 as a proxy for UK supermarkets – miserable.

- Restaurants; there are many examples of restaurant chains that have followed the path, which frequently ends in destruction once the growth momentum falls away. Fortunately, many can be successful for long periods before succumbing to the fate of ubiquity. For that reason, I have always paid attention to new listed restaurant groups. In inheritance tax portfolios, La Tasca, Carluccios and Prezzo were all, for a long period, good investments, which all thankfully ended after being acquired by private equity rather than going the way of Restaurant Group et al. In the case of La Tasca, the entrepreneur behind it, Neil Gatt, went onto build another successful chain, which remains private called Pesto. In the case of Prezzo, the principle driving force was Jonathon Kaye, a member of the legendary Kaye family who, between them, have built up many other restaurant chains over the years from the 1960s to the present. These include Wimpy franchises, Garfunkel’s, ASK and Zizzis. It is usually worth following what businesses that the Kaye family are involved in, which at present is Tasty PLC; like many others this was crushed during the pandemic and has yet to recover. Below is the long-term log chart (until being acquired) of Prezzo

- Outside the UK, Costco is an interesting case. Typically, when a roll-out company comes to market, it does so in order accelerate the rate of expansion, however Costco has been very slow and methodical in its expansion since listing in 2004. Over the past ten years the number of warehouses has increased by just 37%, which represents a compound growth rate of only 3.2%. Consequently, Costco appears to lack the excitement of the growth roll-out story. Nevertheless, it has been a fantastic investment for those who have held it for the past 18 years with the shares increasing 14-fold whilst paying a modest but growing dividend. I wouldn’t however be buying now given the 39x forward PE. Below is the long-term log chart of Costco. Note; a great deal of the performance in recent years has been driven by a stark rerating in the shares.

Roll-up

Roll-up means a company that serially acquires businesses related to a common theme. On the face of it, roll-up stories appear similar to roll-out in that there is a proven concept, frequently started by a talented entrepreneur. The difference is that the majority of growth comes through acquisition. Given the amount of wealth destroyed by poorly executed acquisitions over the years, it can be tempting to recoil at this, however, a disciplined process here can yield decent long-term results for investors. As is the case with all equity investing, I believe the key determinant of success is the quality of management. I summarised what I look for in my previous note on Beazley https://knowledge.sharescope.co.uk/2022/02/18/beazley-plc-property-casualty-insurance-and-diversification-lse-bez/ . The criteria revolve around three pillars, namely Competence, Alignment and Honesty. As stated in the Beazley note, Competence and Alignment are subordinate to Honesty. This is necessarily a qualitative assessment but one should be asking oneself questions about a management team such as:

- Did they do what they said they were going to do?

- Not everything goes according to plan, do they shift blame?

- Do they change the order and style of what they say from one announcement to the next?

Roll-up businesses tend to span a wider range of sectors to roll-out but many can be found in support services and other industrials where the necessary ingredients are in place. These are:

- Fragmentation; to roll-up a sector, there needs to be a lot of opportunities to do so. Many of these businesses need to be small as an acquirer tends to be much larger than the acquirees allowing a more bolt-on approach to purchases rather than the operational headaches that come with transformational acquisitions.

- Variety; which means that there are a lot of businesses servicing often niche parts of the same market and for which there is the potential for some benefit in combining entities.

- Private businesses; one of the reasons to IPO a business is that businesses on the public market attract much higher valuations as the liquidity provided by public markets lowers the risk to business owners. That is to say you can take much more risk (pay more) as an investor if you know you can liquidate your holding than if you know you can’t. This means that acquisitions of private market businesses tend to be cheaper than public market counterparts.

The final point about acquisitions being cheaper is crucial. Whilst nice fluffy strategies that management teams talk about are interesting, the key determinant about the success or otherwise of a roll-up strategy is price paid. Acquirers invariably have larger valuation multiples to the acquirees because of the aforementioned differences in private business and public stock risk. This is effectively an arbitrage that a public market acquirer imposes on private market acquirees.

Putting it another way, the valuation attached to a publicly listed company is effectively an inversion of its cost of capital, whilst the price paid for and acquiree is an inversion of the return on capital. For example, if an acquirer trades on an EV/EBITDA of 16x, its cost of equity 1/16 = 0.0625 or 6.25%, if it makes an acquisition for a business 8x EV/EBITDA, its return on capital is 1/8 = 0.125 or 12.5%. Without any managerial tinkering, the difference in the cost and return doubles the value of the acquisition for the acquirer since 12.5 is double 6.25. Putting it in a more Buffett/Graham-style, price is what you pay and value is what you get and if you pay a low amount in the first place, you’re enjoying an awful lot of margin-of-safety.

In the case of the roll-out strategy, the key is to know when to exit, which is when it is approaching maturity. In the case of roll-up strategies, it is a different set of considerations. Maturity can be a part of the deliberation, but this is difficult since you, as a private investor are unlikely to know what the opportunity set looks like. Instead, investors should concentrate on whether management are doing what they say they’ll do (honesty again).

- The strategy should be clear enough for you to grasp easily. Easily enough to explain to someone else isn’t a bad rule-of-thumb.

- There should be defined parameters including valuation discipline, geographic scope and sectoral scope. Occasionally, it may be necessary to move beyond these parameters but the rationale should be clearly stated and make sense to you as an investor.

- Reporting should be consistent since a business that makes many acquisitions will invariably have increased disclosures. Never trust a business for which the strategy is growth through acquisition but classifies acquisition costs as ‘non-recurring’. Transaction costs are part and parcel of acquisitions and should be treated as ongoing.

Examples

- There are two large Irish businesses listed in London that have successfully deployed this strategy for decades and both are now constituents of the FTSE100, CRH and DCC. In the case of DCC, the name more or less sums up the strategy. DCC stands for Development Capital Corporation. In its very early days, it provided venture capital to start firms but quickly switched to a roll-up strategy. By the time it listed in 1994, it was a well-established (albeit small) acquirer of businesses. Initially, it focused on fuel distribution and sales to retail via gas delivery and operation of petrol stations. However, DCC is an example of a company that has expanded its parameters but, whenever it has done so, management have provided clear rationale for doing so. Today, the company operates in disparate areas including the aforementioned fuel distribution; technology supply chain fulfilment; and healthcare products distribution. Geographically, it operates in the UK and Ireland, mainland Europe, the US and Hong Kong & Macau. The key to its success however is discipline. The management buy businesses without overpaying and integrate them with care. Conceptually simple though obviously more difficult than it sounds. Interestingly, a few years ago, the company raised significant capital to expand its US gas distribution business via acquisitions. The City has become somewhat frustrated with the group however as, in keeping with the discipline, management have not deployed that capital given a dearth of sensibly priced deals resulting in a balance sheet considered by many to be ‘too strong’ (no really!). This should be considered a positive to capital-preservation-minded individual investors however, as the management team show clear discipline by not succumbing to the urge to overpay to make the balance sheet appear more ‘efficient’ and thus please The City. For now, it appears that DCC continues to fulfil the requirements of a roll-up business, since whilst there has been a prolonged pause in expansion in one of its markets, the management are confident that the opportunity remains vast and the commitment to price discipline is admirable. Below is the long-term log chart of DCC. Note the rather average performance since the capital raise about five years ago. With the PE currently sitting at 13x and the dividend yield at 3%, DCC has rarely appeared as good value.

- One company that follows a similar strategy, albeit at much smaller scale is Marlowe. When I was running a fund, it had been a position for the same reasons that DCC had. However, it was removed after what appeared to me to be a divergence from the strategy without management providing a clear rationale for doing so. Marlowe is a consolidator of UK health and safety testing, inspection and certification businesses. The backdrop is compelling; in essence, every commercial property in the UK needs a series of certificates to demonstrate that they meet certain regulatory standards e.g. properly working fire alarms and water quality meeting a certain threshold etc. These regulations have spawned a whole raft small businesses that perform these inspections and issue certificates. Marlowe’s strategy is to make many small acquisitions that consolidate different types of inspection (fire, water, air quality etc) and geography (although entirely in the UK). This then provides a one stop shop for building managers to fulfil their regulatory requirements – all makes sense and management always seemed to pay low multiples (5x to 8x EBITDA). However, I removed this company from the portfolio after it announced that it would make an enormous acquisition of Restore – enormous in the sense that, at the time, Restore was larger than Marlowe. Restore operated in a different sector to Marlowe and would have represented a very different type of acquisition to the typical small, bolt-on approach. I wasn’t the only investor who rejected this and eventually, management had to abandon it. However, the simple attempt to deviate from the strategy was enough for me to lose faith in management. It is entirely feasible that Marlowe would be successful but as an investor one needs discipline and selling when you are uncomfortable with actions by management is perfectly rational. Below is the long-term log chart of Marlowe. Note: data exists before 2015 but that is for a different business as Marlowe was an existing entity that the CEO, Alex Dacre used as a vehicle for his strategy.

Finally, we will briefly examine a roll-up business that operates in a distinctly unsexy area but has been a good place for shareholder capital over the years.

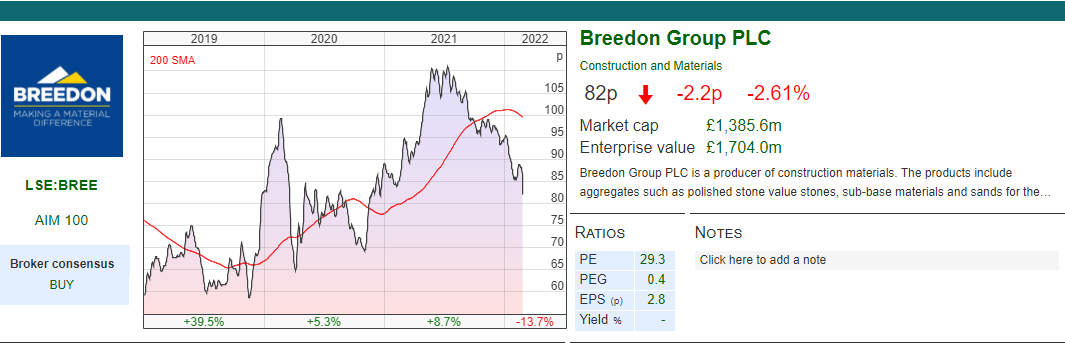

Breedon

Breedon is a UK and Ireland based operator of quarries and cement factories. It was founded by Peter Tom in 2008. Mr Tom had been the CEO of Aggregate Industries, a consolidator of quarries in the 90s and early 2000s. Through disciplined acquisitions, he built the business up to a market capitalisation of almost £2bn before selling out to Holcim at a very full looking multiple in 2005. Mr Tom’s role at Breedon was that of Executive Chairman rather than CEO with former Aggregates Industries Europe CEO, Pat Ward, joining the group later as CEO. The management team was rounded off by Rob Wood as CFO who had previously been group financial controller at Drax.

In 2016, it made its largest acquisition in Hope Construction from Amit Bhatia. This was done via an equity swap making Mr Bhatia the largest shareholder in the expanded group. Peter Tom stepped down at the age of 80 to focus on his other business interest, Leicester Tigers, where he is the chairman. Pat Ward retired shortly afterwards to return to his family in the US. Rob Wood was then made CEO with Amit Bhatia as the chairman.

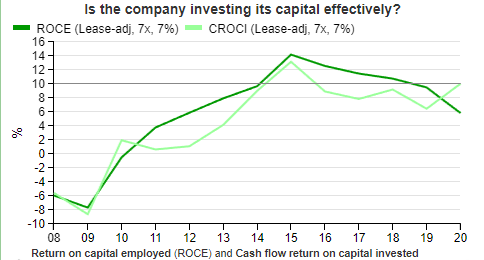

Breedon was founded solely as an acquisition vehicle to continue to consolidate the aggregates and other bulk-building materials sectors. The industry, despite its capital requirements, is attractive because 1. It is very difficult to open new quarries and cement factories given the environmental regulations and 2. Given the high weight to value ratio, it is impractical to source aggregates from long distances. This effectively creates local monopolies allowing quarry owners to extract reasonable returns. Unspectacular for sure, but reasonable enough to generate attractive shareholder returns.

Ownership

Mr Bhatia remains the largest holder with around 10% of the equity via his Abicad Holdings vehicle. Lansdowne Partners own 9.2% as part of their bull case for UK infrastructure spending of which Breedon is a big beneficiary. Several other institutions own between 3% and 8% including Soros’s investment vehicle.

Valuation

Typically, Breedon has suffered the same problem as many good quality AIM-listed stocks; that of a high valuation on account of the passive bid from inheritance tax portfolios. Nevertheless, the PE currently sits at around 13x and given the capex over the next couple of years, the price to book value is around 1.3x. Compared to its history, this would be towards the low end of its valuation and seems reasonable investment in a potentially inflationary world given its well-financed asset-backed balance sheet of unrepeatable quarries and cement factories.

Opinion

Breedon has seemed in flux since the retirements of Peter Tom and Pat Ward. Nevertheless, Rob Wood seems very capable and understands his opportunity set. The chairman owns 10%, worth £140m and one would hope therefore that management is well aligned with shareholder interests. It isn’t a get rich quick investment given the plodding nature of the industry but might be a get rich slowly story.

Jamie Ward

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Hi Jamie

Totally agree with your thinking. I have been holding Breedon since it was a penny stock and see no reason to get out now.

Breedon has come back into the value range recently and I have added to my holding waiting for the next move up.

Paul

I like Breedon and I think it is underappreciated. SigmaRoc also appears to be following a somewhat similar strategy. A well executed roll up strategy can be hugely profitable. We held Bunzl for a number of years whilst it was being run by Michael Roney and Bryan May but lost faith in it after Bryan May left as it seemed some of the discipline had diminished.

Jamie