Over the years I have ignored Kingspan because it is big, acquisitive, and supplies building materials.

My gut reaction to these facts is that Kingspan is best avoided. It is big, so its best years of growth may be behind it; it is risky because it has been cobbled together from acquisitions; and its products are not particularly special. A builder probably does not care much which company he buys them from.

These are, of course, prejudices. I changed the filter I use to discover new shares and how I evaluate these ideas in SharePad specifically to challenge my prejudices and perhaps find good investments where previously I had not looked.

My gut could be wrong about Kingspan on all three counts.

Kingspan by the numbers

My version of SharePad’s Single Page Summary reveals many reasons to like the company and few reasons not to.

Let us get a troublesome statistic out of the way first. Kingspan’s market capitalisation is big (€13 billion).

Companies generally have to work harder to grow as they get bigger. If, for example, they already supply a substantial part of the market, they may have to diversify, which makes them more complicated and difficult to analyse. They may not be as good at the new things they do as they are at the activities that got them this far.

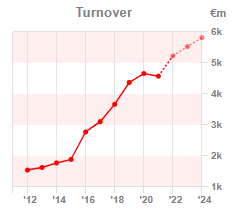

Jim Slater said “elephants don’t gallop”, although Terry Smith has shown that gigantic companies can canter. Kingspan has been on a canter:

If the analysts’ predictions (the dotted part of the line) are right, the company will have nearly quadrupled turnover over the twelve-year period to 2024. So far, it has suffered the slightest of dips in turnover only once, in the year just gone by, which included the first Covid lockdown.

Kingspan could be growing and simultaneously destroying value by adding new businesses of lower quality and eroding profitability, but the last four years of data suggest otherwise:

I have excluded Goodwill in the calculation of Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) because goodwill is the historical premium paid for acquisitions, and will not form part of the ongoing operating costs of the business in its current form.

20% ROCE in a bad year, the only year in recent history when turnover has actually fallen, is a very decent return, especially since Kingspan typically earns even more in cash terms.

A 10% profit margin might also suggest that Kingspan’s products are more than just commodities, since it can sell them for considerably more than it costs to supply them. Perhaps they are special after all.

Debt was stable prior to the pandemic and fell sharply in 2020. The share count is rising gradually but only sufficiently to pay for share option schemes. The main complicating factor is acquisitions.

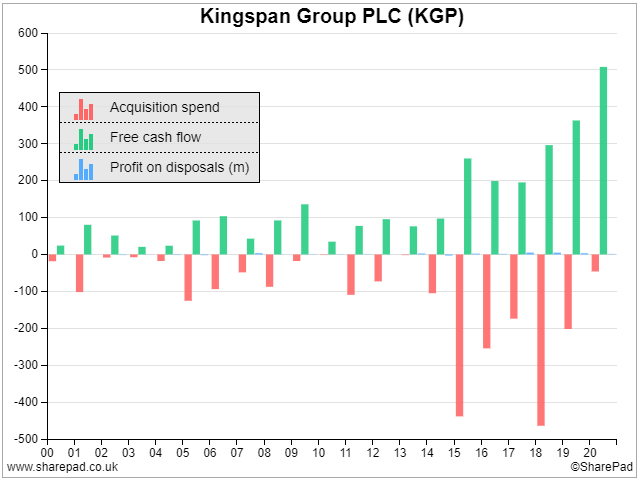

Kingspan did not spend much on acquisitions in 2020, like most companies it cut investment to conserve cash and weather the pandemic. The chart below, though, reveals the familiar pattern of a roll-up. Most years, Kingspan spends much of its free cash flow on acquisitions:

As I have explained before, a roll-up buys mini-versions of itself. It is perhaps the least risky way to grow by acquisition. Because the target businesses are small, the acquirer can fund the acquisitions out of cash flow rather than increasing its level of borrowing or raising more money from shareholders. Because the target companies are similar, they should slot in relatively painlessly.

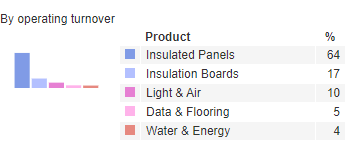

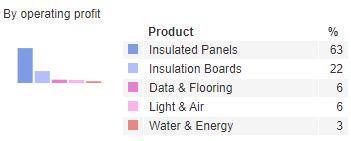

Kingspan’s segmental chart supports the roll-out theory. 81% of revenue in 2020 and 85% of profit came from insulation panels and boards, so Kingspan, originally an insulation business, bought lots of other insulation businesses:

|

|

In case you are wondering who buys all this insulation, the company’s acquisitions have taken it on a round-the-world trip (documented here). Founded in Ireland, Kingspan earns 55% of revenue in Europe (excluding Britain), 20% in the Americas, 16% in Britain and 10% elsewhere.

To get the full picture of this analysis we must leave SharePad and look for colour on the company’s website and in its annual report. But before we do there is one other positive thing to glean about Kingspan from SharePad’s Single Page Summary: Founder and chairman Eugene Murtagh still owns 15% of the business.

How Kingspan does it

Kingspan describes itself as a global leader in high performance insulation and building envelopes, although it might be more accurate to say it is a global leader in insulation, and would like to be a global leader in the rest of the building envelope.

The envelope is the boundary between the inside and the outside of a building. Critically it controls the transfer of light, noise, heat and water, helping to maintain a comfortable environment inside.

“Completing the envelope” is the fourth element of the company’s strategy and perhaps the most risky as it involves making and selling different products. It is, however, plausible that other aspects of the envelope, roofing membranes for example, have similar qualities to insulation and are specified and bought by the same architects, consultants and builders.

The first element of the strategy is innovation. Kingspan says it is challenging builders with new materials and digital technologies, which should help it with the second element which is to reduce its environmental impact. The third element is global expansion, which like the first, is a way of getting bigger.

The question is whether the imperative to get bigger through product and geographical diversification can coexist comfortably with the aspiration to be innovative. Big companies are often less nimble and have an interest in maintaining the status quo, but maybe a company with a very special culture could do it.

This is where Kingspan’s owner-managers come into play. The biography of 78 year-old Eugene Murtagh in Kingspan’s 2020 annual report says “he sets the tone at the top, developing and embedding values.”

No doubt his son and chief executive officer since 2005, Gene Murtagh, is happy to take his lead.

Kingspan’s website profiles employees to encourage potential recruits, hinting at the kind of employee-focused culture that could drive innovation and sales of innovative products.

Too good to be true?

While the story I have pulled together so far is superficial and uncritical, I think it is also broadly correct. Kingspan is a good business, it probably does make superior products. But investors will need to consider the revelations coming out of the Grenfell Inquiry and Kingspan’s response before affirming this*.

Despite that it may still be a very difficult business to buy and hold.

The reason for that is not to be found in the company, but the industry it supplies: construction, which is very sensitive to the economy. This effect exerts a disproportionate impact on share prices.

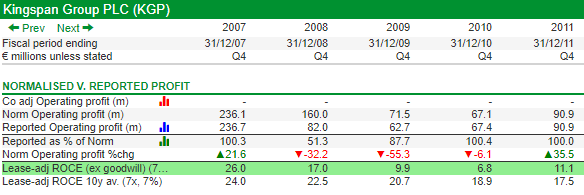

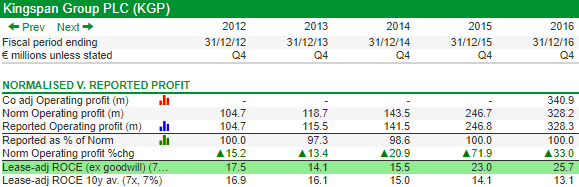

We can see the impact of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) on Kingspan’s performance. Profitability declined from levels comparable to recent years (26% ROCE in 2007) to just 7% ROCE in 2010 after three consecutive years of profit declines:

The company addresses the cyclical risk in the annual report. Its main defence is global diversification. In 2008, half of Kingspan’s turnover was from the UK, however the fact that only 16% of revenue is earned in Britain today gives it only limited protection. The financial crisis in 2008 was after all a global financial crisis, and the next great recession could be too.

The contraction in construction as a result of the GFC was not short-lived. By 2011, the first year of profit growth since 2008, Kingspan’s ROCE had only increased to 11%.

It was not until 2015 that Kingspan lifted ROCE back up above 20%:

Even today, Kingspan’s ten year average ROCE is only 12.8%, up from a low of 11.8% in 2018.

Judging Kingspan by its ROCE in recent years ignores the probability that it could be less profitable again in the future.

Judging the company by its single year profit multiple, its PE ratio for example, might be misleading too.

One way around the problem of judging the share price is to compare it to something less volatile than profit: turnover, for example.

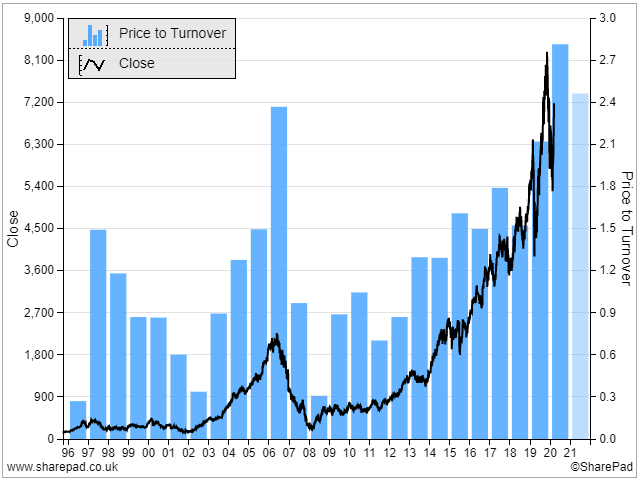

Between 2007 and 2008 Kingspan’s share price (black line) crashed 91%. Back then, we could have bought the company for about 0.3 times its turnover (blue bars).

Since then, the share price has risen 3,250% and the price has gone up to 2.4 times turnover.

The chart suggests low price to turnover may be predictive of good returns, at least for a while. We are not there now, and if we were and I were to buy the shares, I would always be wondering at what point to sell.

While I own shares in some businesses that supply the construction sector like Dewhurst, a manufacturer and distributor of lift components, and FW Thorpe, a manufacturer of lighting systems, they have been more resilient in recessions.

Diversification may have helped them too, but I think perhaps the fact that they do not supply elements of the building envelope is beneficial. During downturns maintenance and refurbishment work keeps them going. Kingspan is probably more dependent on new builds.

Richard Beddard

Kingspan is not the only listed roll-up supplying the construction industry. Miles Ruffel responded to my original article on roll-ups to recommend Brickability, a specialist brick distributor that floated in 2019. It was founded in 1984, has grown by acquisition and continues to diversify both geographically and by product type (into roofing for example) by acquiring other suppliers.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

*This sentence was added after publication. I had not made the connection between Kingspan and the tragedy at Grenfell and thank Dave, a reader, for enlightening me. The company’s failings cast doubt on its culture, and investors thinking of buying the shares will have to decide whether its subsequent actions are sufficient.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.