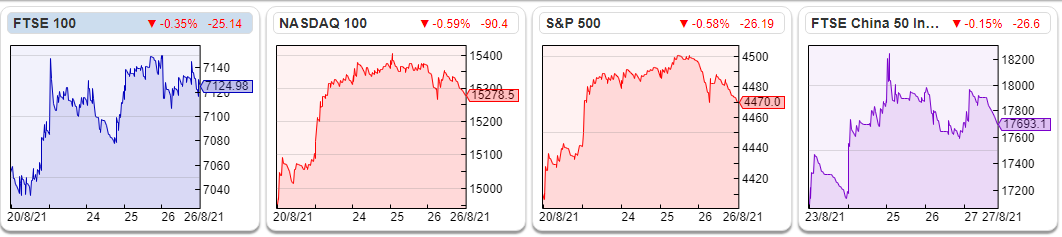

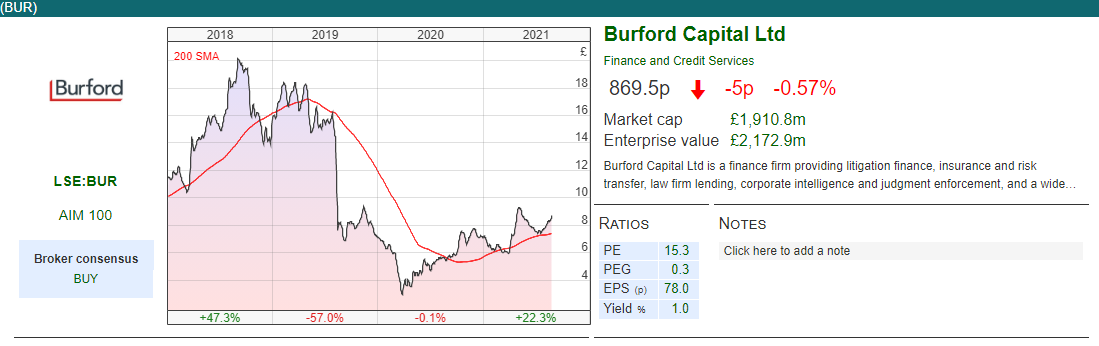

The FTSE 100 was up half a percent last week to 7,124. The Nasdaq 100 had a better week +1.2% and the China 50 rebounded +4.5%, though that index is still down -14% in the last 3 months. The US 10-year bond yield finished last week at 1.35%, recovering from a low of 1.19% in early August. It feels like the next month or two will be particularly important for determining how good the vaccines are at preventing hospitalisations.

Earlier this month Digital Turbine announced they’d completed the acquisition of Fyber, Lars Windhorst’s Berlin based adtech business that I’d previously helped with their investor relations. A few years ago, Fyber management believed that investors wouldn’t want to see statutory PBT (there weren’t any profits actually) in their investor presentation, preferring EBITDA as a measure of progress. I thought I was being helpful pointing out that investors pay far more attention to profits (and losses) than adjusted EBITDA. Strangely though, that wasn’t the sort of insight that management appreciated, soon afterwards the Investor Relations firm that I worked for made me redundant. Good luck to them, but I do really struggle with valuations in adtech in the US, for instance Digital Turbine, who acquired Fyber, are on 76x PER, 60x EV/EBITDA and 16x sales ratio.

A couple of years ago Michael Mauboussin looked at the history of EBITDA. He quotes a survey that reveals companies that emphasize EBITDA are on average smaller, more indebted, more capitally intensive and less profitable than their peers.* Odd that.

Though an emphasis on adjusted EBITDA is a red flag to me, it is not an entirely stupid concept. Apparently EBITDA was first used in the 1970s by John Malone at TCI, the cable company. He had figured out that a successful cable company should not be trying to maximise accounting profits. Instead if management were confident that their spend on digging cables in the ground would increase paying subscriber households who generate cashflow, then a cable company could reduce taxes by using a high depreciation charge to decrease taxable profits. Taxes could then be reduced further by borrowing money, investing in the business and offsetting the interest expense against profits. Although the higher interest charge also created some risk – unlike taxes which reduce as accounting profits fall – the interest payable on the debt remains constant even as operating conditions worsen.

What Malone realised, and others didn’t, was that there were returns to scale/network effects in the cable TV industry: programming costs per subscriber fell as the company grew. With that in mind, there was no point in trying to maximise the current year’s accounting profits, or reported ROCE, he knew that keeping profits low and ploughing money back into the business made more sense. But if you’re a public company, reporting consistently lower profits than your peers is difficult. Hence rather than profits and EPS, Malone shifted the narrative and emphasised EBITDA to show progress to bankers and investors.

Then in the 1980s LBO boom Private Equity firms took note and realised that EBITDA was useful for encouraging bankers to lend them money to gear up the balance sheets of target companies with stable revenue. Later in the 1990s investment bankers in the TMT bubble realised that EV/EBITDA multiples could be used to justify higher valuations than more conservative ratios like dividend yield, price to book or price earnings.

Malone eventually sold TCI to AT&T for $48bn Enterprise Value ($32bn in stock and $16bn in assumed debt). TCI had generated a 30% CAGR, it was a 900 bagger over the Malone era, according to Thorndike. This was clearly a business with a “moat”, but a very different type of moat than high Return on Capital businesses like Apple, Facebook and Microsoft. There are more similarities with Malone’s company and Netflix (CROCI 6.5%) and Amazon (CROCI 16%).

However, adjusted EBITDA is also favoured by companies where growth is not creating any value. WeWork failed to convince investors that “community adjusted EBITDA” justified its high valuation; the IPO was pulled and the company nearly collapsed.

However, adjusted EBITDA is also favoured by companies where growth is not creating any value. WeWork failed to convince investors that “community adjusted EBITDA” justified its high valuation; the IPO was pulled and the company nearly collapsed.

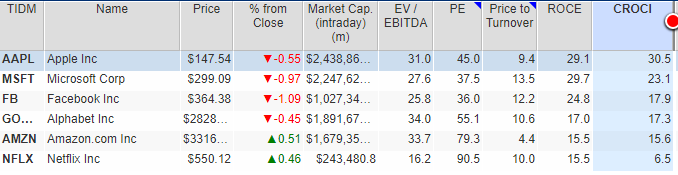

Vodafone also is superficially similar to TCI, demonstrating very strong debt funded revenue growth in the 1990s as it invested in its mobile network, made acquisitions and offered incentives to acquire mobile phone customers. Yet despite being a network operator, there were no network effects for the UK telco. Vodafone’s international expansion, ongoing cost of infrastructure investment and bidding for 3G and 4G licences meant that the returns to scale were lacking compared to Malone’s cable TV business. Hence Vodafone’s share price fell 75% to £1 when the TMT bubble burst and the share price then drifted sideways for the next 20 years.

My impression is that most managements like to emphasise EBITDA because it suggests growth is creating value, even when it is not. But there a few companies who are using the measure properly, with Malone’s insight in mind. Sadly, I don’t think that there is an easy way to tell the difference, it comes down to trusting that management are reinvesting the cashflow back into their business to fund growth wisely.

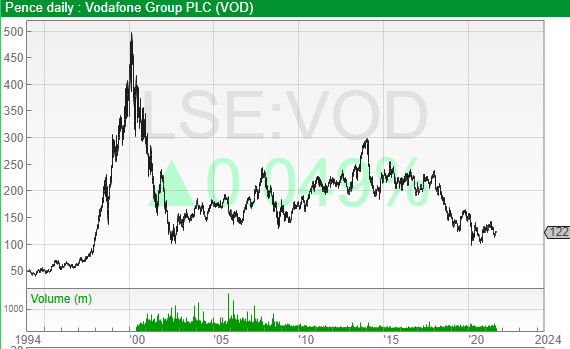

This week I look at a couple of businesses where lower accounting profits could signal better times to come: Burford put out an H1 update and an intriguing accounting change (cost accruals) that reduces profits and Sopheon, which released H1 results where lower profits are a result of a switch to the SaaS (Software as a Service) recurring revenue model and hiring more sales and marketing staff. Plus SigmaRoc, the acquisitive quarry company, that is up +170% in the last 3 years and which, incidentally, seems a big fan of EBITDA.

Finally it’s with sadness that I learnt last week that Jeremy Grime, who used to write this weekly column, has died. Jeremy was a fun character, full of entertaining anecdotes and I personally owe him much gratitude for recommending me for this role at SharePad last year when he left to go back into full time stockbroking. His funeral is Thurs, 16th September in Malpas, Cheshire. Please contact me on Twitter or through SharePad if you’d like to attend and I can send you further details.

Burford H1 June update

A curious H1 update from Burford. The litigation finance company said that it expects to report $142m of capital provision income (revenue by any other name) and $20m PAT on a comparable basis. That’s down steeply -44% and -87% respectively vs H1 last year. In addition, management flagged an accounting change that will make the group loss-making in H1. Burford management have decided to change their accounting policy, to accrue costs in line with the Fair Value gains which reduces profit after tax still further, to a H1 loss of $70m. The shares were initially down 8% on the morning of the RNS, before recovering most of the lost ground later in the day. I’ve owned the shares since before the Muddy Waters attack, and increased my position when the price fell below £5 per share following their report in August 2019.

A curious H1 update from Burford. The litigation finance company said that it expects to report $142m of capital provision income (revenue by any other name) and $20m PAT on a comparable basis. That’s down steeply -44% and -87% respectively vs H1 last year. In addition, management flagged an accounting change that will make the group loss-making in H1. Burford management have decided to change their accounting policy, to accrue costs in line with the Fair Value gains which reduces profit after tax still further, to a H1 loss of $70m. The shares were initially down 8% on the morning of the RNS, before recovering most of the lost ground later in the day. I’ve owned the shares since before the Muddy Waters attack, and increased my position when the price fell below £5 per share following their report in August 2019.

Accounting change Burford doesn’t pay cash bonuses, or any other incentives, based on Fair Value accounting write ups (unlike Enron or banks pre credit crisis.) However when gains are realised the eligible employees are paid a “carry” based on the vintage (ie when disputes from a particular year are resolved.) This approach meant that assets were written up through the p&l, but no corresponding costs were recognised until the dispute was resolved and Burford received their money. Burford is now going to recognise costs earlier (which reduces profits in the short term).

The change means $20m profit after tax swings to a $70m H1 2021 loss. Of that $90m negative swing, $45m is cost accruals from YPF/Petersen case, where Burford is suing the Argentinian Government to recover losses over the expropriated oil company, and which is currently valued on Burford’s balance sheet at $773m, the vast majority of which is a Fair Value write up. There’s also a $34m cost accrual against the controversial asset recovery business, where Burford chases individual or corporates who have had a court ruling against them, but have refused to settle.

Management also said that they are considering changing to US GAAP (from IFRS) at the end of the year, which makes sense given the dual listing in New York and attempt to appeal to US investors. Although I understand the reasons for Fair Value accounting, I think investors would probably appreciate more historic cost disclosure, and then they can make assumptions about future returns themselves.

Results The results themselves look disappointing with realised gains more than halving from $177m H1 2020 to $77m this H1, and profit after tax of just $20m (down 87% vs H1 last year) even before the accounting change. Burford management have always warned that six month results are likely to be lumpy, with some halves more positive than others. Despite the steep fall in profits, returns (as measured by the company’s completed case ROIC) were only down slightly vs H1 last year to 95%, so it does look like this has been caused by Covid delaying settlements, rather than Burford losing completed cases. On the positive side, Burford had $430m of cash on their balance sheet at the end of June, which didn’t include the further $103m that they received from the Akmedov divorce case in July.

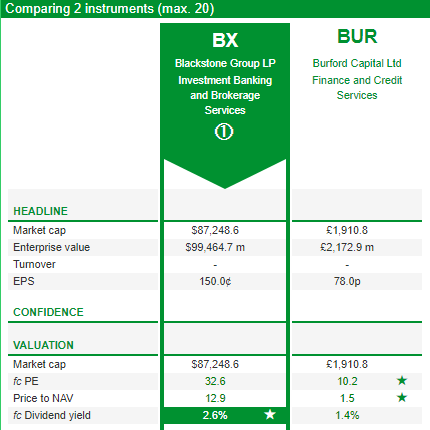

Opinion The game that management are playing here is not to massage up numbers with accounting shenanigans. This change to accrual accounting increases costs in the near term and reduces profits. Instead, I think that this is an attempt to make themselves comparable to the likes of Blackstone, which accrues costs in line with Burford’s new accounting treatment and reports using US GAAP. The calculation that Burford’s management seem to be making is that a reduction in profits will be more than offset by an increase in the multiple investors are prepared to pay for accounting numbers that they can have greater confidence in.

Blackstone has a market cap of $87bn, trades on a forecast PER of 32x and a Price to Tangible NAV of 13x, which compares to Burford’s 10x PER and 1.5 P/ NAV.

Under cross examination I wonder if Chris Boggart, Chief Exec of Burford might admit to deliberately trying to present the litigation finance group in a similar light to Steve Schwarzman’s much more highly rated private equity vehicle? The catalyst for a significant re-rating is the case against Argentina which is expected to be heard early next year. The chart shows that there seems to be a nice bowl forming.

Under cross examination I wonder if Chris Boggart, Chief Exec of Burford might admit to deliberately trying to present the litigation finance group in a similar light to Steve Schwarzman’s much more highly rated private equity vehicle? The catalyst for a significant re-rating is the case against Argentina which is expected to be heard early next year. The chart shows that there seems to be a nice bowl forming.

Sopheon H1 to June

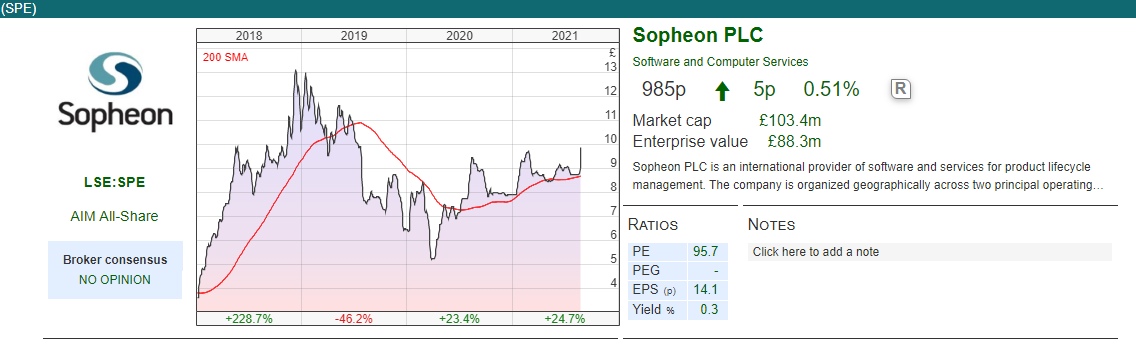

Sopheon, which sells software helping companies manage their innovation and New Product Development process, released H1 results to June with revenues +19% to $16.5m. H1 PBT was £518K and adjusted EBITDA was $2.8m.

Sopheon, which sells software helping companies manage their innovation and New Product Development process, released H1 results to June with revenues +19% to $16.5m. H1 PBT was £518K and adjusted EBITDA was $2.8m.

Because the company has 98% Gross Annual Recurring Revenue, they can say that FY revenue visibility is now $31m (versus $25.5m this time last year, and $30m 2020 Actual). Richard covered the company in July in detail here, and I don’t have much to add to his analysis, except to say that lower profitability in H2 may be signalling better performance to come.

Broker forecasts FinnCap is their broker, and have left their forecasts unchanged with FY2021 revenue expected to be $33m and EPS $c1.6, rising to $c3.3 FY 2022F. Andrew Darley, the analyst covering SPE has put in his research note that his forecasts do look somewhat “daft”. That’s because the company has already achieved 63% of FY EBITDA and Andy’s current PBT forecast implies a loss in H2. Sopheon has in previous years reported better than expected Q4 licence sales, as a result of the buying cycle for its products. Managers tend to wait until the end of the year before committing large amounts of their budget on software, hence forecasting a loss in H2 seems rather pessimistic for their broker.

I used to work with Andy, and I think that the unchanged forecasts are not because he’s having a bad day at the office. Instead management have signalled to him that costs may rise from new hires in H2, which shows confidence. If management can get this right, it’s an example of investing in the business, foregoing current profits to drive revenue growth and returns on capital in future. I also suspect that given the highly uncertain last 18 months (Sopheon experienced unusually high levels of customer churn during the pandemic) management prefer to err on the side of conservatism when it comes to the numbers that their broker publishes.

Opinion This looks like it could be an interesting story, with profits this year suppressed because of the switch to SaaS/recurring revenues and management investing in the business. SPE is trading on 4.0x 2022F sales. For this market that appears attractive for a 71% gross margin, subscription revenue business.

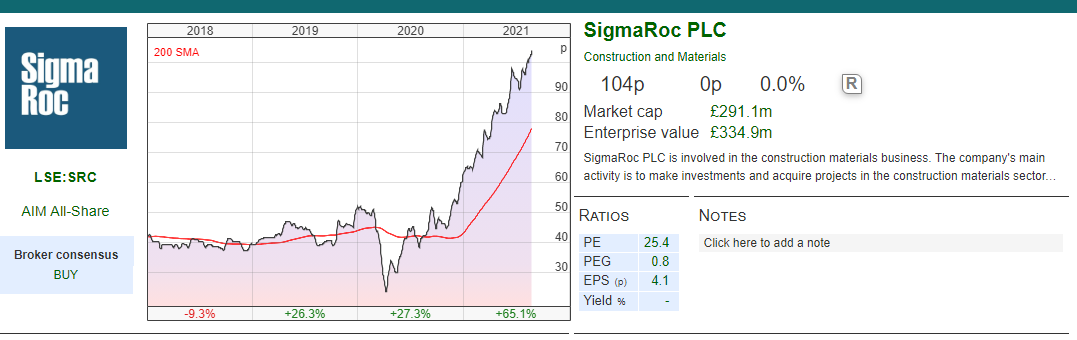

SigmaRoc acquisition of Nordkalk

This acquisitive concrete company that has been buying up quarries in the Channel Islands, UK and Belgium announced another significant acquisition. They are buying Nordkalk, a Finnish company that owns limestone quarries across the Nordic region and Northern Europe. Building materials like stone and concrete are heavy, which means there’s limited ability for China or other low cost countries to compete; because transport costs are a large share of the materials’ cost, it makes sense to have a local supplier.

This acquisitive concrete company that has been buying up quarries in the Channel Islands, UK and Belgium announced another significant acquisition. They are buying Nordkalk, a Finnish company that owns limestone quarries across the Nordic region and Northern Europe. Building materials like stone and concrete are heavy, which means there’s limited ability for China or other low cost countries to compete; because transport costs are a large share of the materials’ cost, it makes sense to have a local supplier.

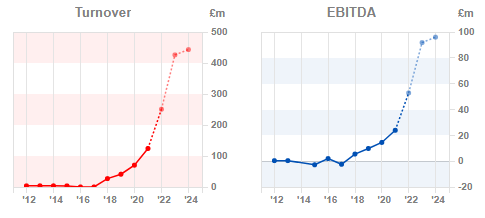

Nordkalk generated revenues of €276m and underlying EBITDA of €67m in 2020. So the target is actually larger than the acquirer, SigmaRoc, which generated £124m and EBITDA of £21m in 2020.

The price SigmaRoc is going to pay is €500m Enterprise Value for Nordkalk, funded with an extended £305m credit facility from Santander and BNP Paribas and £260m equity raise (versus a SigmaRoc market cap of £290m pre announcement). Rettig Group, a Finnish family-owned investment vehicle, who own a stake in Nordkalk will become an 8% shareholder in the enlarged group and have agreed to a 12 month lock up.

Trading update In the same RNS, the company also announced an H1 2020 to June update for both businesses. SigmaRoc revenues were £85m and underlying EBITDA was £15m, representing an increase of +13% and +14%, respectively, over the same period in 2020. Nordkalk generated revenues of £127m (€145m) and EBITDA of £31m (€36m), lower revenue growth +8% but higher EBITDA growth +17%, over the same first half period in 2020. That suggests proforma annualised historic revenues of £424m and adjusted EBITDA of £92m, versus a combined Enterprise Value of around £730m (so proforma EV/EBITDA of 8x vs Breedon 10x EV/EBITDA 2021F).

Opinion Management present a good investment case suggesting that although there are much larger global concrete companies like Lafarge Holcim, there is potential for a regional business to consolidate local quarries, and also buy unwanted subsidiaries from the global players. It’s a similar strategy to Jim Ratcliffe at Ineos, who bought ICI and BP’s unwanted bits, and is now top of The Sunday Times rich list.

You might not think concrete is the most exciting industry, but Breedon Group is up 5x in the last 10 years. I’ve long believed that it is worth spending the time to understand overlooked sectors like this, or shipping (Clarkson and Ocean Wilsons) or computer games (pre pandemic). Everyone seems to have an opinion on supermarkets and banks, because they’re so familiar. Whereas concrete, well there just aren’t that many people interested in concrete. So a keen investor can create an “edge”, although it might make your conversation a bit dull at parties.

What I don’t have a feel for is i) amount of future capex that SigmaRoc requires ii) cyclical nature of the industry is. So I think if you’re prepared to take the time to understand those variables, then this could continue to do well.

Bruce Packard

Notes

The author owns shares in Burford

*The Prevalence and Validity of EBITDA as a Performance Measure A Verriest, J Bouwens, T De Kok.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Weekly Commentary 31/08/21: Lower profits, improving performance?

The FTSE 100 was up half a percent last week to 7,124. The Nasdaq 100 had a better week +1.2% and the China 50 rebounded +4.5%, though that index is still down -14% in the last 3 months. The US 10-year bond yield finished last week at 1.35%, recovering from a low of 1.19% in early August. It feels like the next month or two will be particularly important for determining how good the vaccines are at preventing hospitalisations.

Earlier this month Digital Turbine announced they’d completed the acquisition of Fyber, Lars Windhorst’s Berlin based adtech business that I’d previously helped with their investor relations. A few years ago, Fyber management believed that investors wouldn’t want to see statutory PBT (there weren’t any profits actually) in their investor presentation, preferring EBITDA as a measure of progress. I thought I was being helpful pointing out that investors pay far more attention to profits (and losses) than adjusted EBITDA. Strangely though, that wasn’t the sort of insight that management appreciated, soon afterwards the Investor Relations firm that I worked for made me redundant. Good luck to them, but I do really struggle with valuations in adtech in the US, for instance Digital Turbine, who acquired Fyber, are on 76x PER, 60x EV/EBITDA and 16x sales ratio.

A couple of years ago Michael Mauboussin looked at the history of EBITDA. He quotes a survey that reveals companies that emphasize EBITDA are on average smaller, more indebted, more capitally intensive and less profitable than their peers.* Odd that.

Though an emphasis on adjusted EBITDA is a red flag to me, it is not an entirely stupid concept. Apparently EBITDA was first used in the 1970s by John Malone at TCI, the cable company. He had figured out that a successful cable company should not be trying to maximise accounting profits. Instead if management were confident that their spend on digging cables in the ground would increase paying subscriber households who generate cashflow, then a cable company could reduce taxes by using a high depreciation charge to decrease taxable profits. Taxes could then be reduced further by borrowing money, investing in the business and offsetting the interest expense against profits. Although the higher interest charge also created some risk – unlike taxes which reduce as accounting profits fall – the interest payable on the debt remains constant even as operating conditions worsen.

What Malone realised, and others didn’t, was that there were returns to scale/network effects in the cable TV industry: programming costs per subscriber fell as the company grew. With that in mind, there was no point in trying to maximise the current year’s accounting profits, or reported ROCE, he knew that keeping profits low and ploughing money back into the business made more sense. But if you’re a public company, reporting consistently lower profits than your peers is difficult. Hence rather than profits and EPS, Malone shifted the narrative and emphasised EBITDA to show progress to bankers and investors.

Then in the 1980s LBO boom Private Equity firms took note and realised that EBITDA was useful for encouraging bankers to lend them money to gear up the balance sheets of target companies with stable revenue. Later in the 1990s investment bankers in the TMT bubble realised that EV/EBITDA multiples could be used to justify higher valuations than more conservative ratios like dividend yield, price to book or price earnings.

Malone eventually sold TCI to AT&T for $48bn Enterprise Value ($32bn in stock and $16bn in assumed debt). TCI had generated a 30% CAGR, it was a 900 bagger over the Malone era, according to Thorndike. This was clearly a business with a “moat”, but a very different type of moat than high Return on Capital businesses like Apple, Facebook and Microsoft. There are more similarities with Malone’s company and Netflix (CROCI 6.5%) and Amazon (CROCI 16%).

Vodafone also is superficially similar to TCI, demonstrating very strong debt funded revenue growth in the 1990s as it invested in its mobile network, made acquisitions and offered incentives to acquire mobile phone customers. Yet despite being a network operator, there were no network effects for the UK telco. Vodafone’s international expansion, ongoing cost of infrastructure investment and bidding for 3G and 4G licences meant that the returns to scale were lacking compared to Malone’s cable TV business. Hence Vodafone’s share price fell 75% to £1 when the TMT bubble burst and the share price then drifted sideways for the next 20 years.

My impression is that most managements like to emphasise EBITDA because it suggests growth is creating value, even when it is not. But there a few companies who are using the measure properly, with Malone’s insight in mind. Sadly, I don’t think that there is an easy way to tell the difference, it comes down to trusting that management are reinvesting the cashflow back into their business to fund growth wisely.

This week I look at a couple of businesses where lower accounting profits could signal better times to come: Burford put out an H1 update and an intriguing accounting change (cost accruals) that reduces profits and Sopheon, which released H1 results where lower profits are a result of a switch to the SaaS (Software as a Service) recurring revenue model and hiring more sales and marketing staff. Plus SigmaRoc, the acquisitive quarry company, that is up +170% in the last 3 years and which, incidentally, seems a big fan of EBITDA.

Finally it’s with sadness that I learnt last week that Jeremy Grime, who used to write this weekly column, has died. Jeremy was a fun character, full of entertaining anecdotes and I personally owe him much gratitude for recommending me for this role at SharePad last year when he left to go back into full time stockbroking. His funeral is Thurs, 16th September in Malpas, Cheshire. Please contact me on Twitter or through SharePad if you’d like to attend and I can send you further details.

Burford H1 June update

Accounting change Burford doesn’t pay cash bonuses, or any other incentives, based on Fair Value accounting write ups (unlike Enron or banks pre credit crisis.) However when gains are realised the eligible employees are paid a “carry” based on the vintage (ie when disputes from a particular year are resolved.) This approach meant that assets were written up through the p&l, but no corresponding costs were recognised until the dispute was resolved and Burford received their money. Burford is now going to recognise costs earlier (which reduces profits in the short term).

The change means $20m profit after tax swings to a $70m H1 2021 loss. Of that $90m negative swing, $45m is cost accruals from YPF/Petersen case, where Burford is suing the Argentinian Government to recover losses over the expropriated oil company, and which is currently valued on Burford’s balance sheet at $773m, the vast majority of which is a Fair Value write up. There’s also a $34m cost accrual against the controversial asset recovery business, where Burford chases individual or corporates who have had a court ruling against them, but have refused to settle.

Management also said that they are considering changing to US GAAP (from IFRS) at the end of the year, which makes sense given the dual listing in New York and attempt to appeal to US investors. Although I understand the reasons for Fair Value accounting, I think investors would probably appreciate more historic cost disclosure, and then they can make assumptions about future returns themselves.

Results The results themselves look disappointing with realised gains more than halving from $177m H1 2020 to $77m this H1, and profit after tax of just $20m (down 87% vs H1 last year) even before the accounting change. Burford management have always warned that six month results are likely to be lumpy, with some halves more positive than others. Despite the steep fall in profits, returns (as measured by the company’s completed case ROIC) were only down slightly vs H1 last year to 95%, so it does look like this has been caused by Covid delaying settlements, rather than Burford losing completed cases. On the positive side, Burford had $430m of cash on their balance sheet at the end of June, which didn’t include the further $103m that they received from the Akmedov divorce case in July.

Opinion The game that management are playing here is not to massage up numbers with accounting shenanigans. This change to accrual accounting increases costs in the near term and reduces profits. Instead, I think that this is an attempt to make themselves comparable to the likes of Blackstone, which accrues costs in line with Burford’s new accounting treatment and reports using US GAAP. The calculation that Burford’s management seem to be making is that a reduction in profits will be more than offset by an increase in the multiple investors are prepared to pay for accounting numbers that they can have greater confidence in.

Blackstone has a market cap of $87bn, trades on a forecast PER of 32x and a Price to Tangible NAV of 13x, which compares to Burford’s 10x PER and 1.5 P/ NAV.

Sopheon H1 to June

Because the company has 98% Gross Annual Recurring Revenue, they can say that FY revenue visibility is now $31m (versus $25.5m this time last year, and $30m 2020 Actual). Richard covered the company in July in detail here, and I don’t have much to add to his analysis, except to say that lower profitability in H2 may be signalling better performance to come.

Broker forecasts FinnCap is their broker, and have left their forecasts unchanged with FY2021 revenue expected to be $33m and EPS $c1.6, rising to $c3.3 FY 2022F. Andrew Darley, the analyst covering SPE has put in his research note that his forecasts do look somewhat “daft”. That’s because the company has already achieved 63% of FY EBITDA and Andy’s current PBT forecast implies a loss in H2. Sopheon has in previous years reported better than expected Q4 licence sales, as a result of the buying cycle for its products. Managers tend to wait until the end of the year before committing large amounts of their budget on software, hence forecasting a loss in H2 seems rather pessimistic for their broker.

I used to work with Andy, and I think that the unchanged forecasts are not because he’s having a bad day at the office. Instead management have signalled to him that costs may rise from new hires in H2, which shows confidence. If management can get this right, it’s an example of investing in the business, foregoing current profits to drive revenue growth and returns on capital in future. I also suspect that given the highly uncertain last 18 months (Sopheon experienced unusually high levels of customer churn during the pandemic) management prefer to err on the side of conservatism when it comes to the numbers that their broker publishes.

Opinion This looks like it could be an interesting story, with profits this year suppressed because of the switch to SaaS/recurring revenues and management investing in the business. SPE is trading on 4.0x 2022F sales. For this market that appears attractive for a 71% gross margin, subscription revenue business.

SigmaRoc acquisition of Nordkalk

Nordkalk generated revenues of €276m and underlying EBITDA of €67m in 2020. So the target is actually larger than the acquirer, SigmaRoc, which generated £124m and EBITDA of £21m in 2020.

The price SigmaRoc is going to pay is €500m Enterprise Value for Nordkalk, funded with an extended £305m credit facility from Santander and BNP Paribas and £260m equity raise (versus a SigmaRoc market cap of £290m pre announcement). Rettig Group, a Finnish family-owned investment vehicle, who own a stake in Nordkalk will become an 8% shareholder in the enlarged group and have agreed to a 12 month lock up.

Trading update In the same RNS, the company also announced an H1 2020 to June update for both businesses. SigmaRoc revenues were £85m and underlying EBITDA was £15m, representing an increase of +13% and +14%, respectively, over the same period in 2020. Nordkalk generated revenues of £127m (€145m) and EBITDA of £31m (€36m), lower revenue growth +8% but higher EBITDA growth +17%, over the same first half period in 2020. That suggests proforma annualised historic revenues of £424m and adjusted EBITDA of £92m, versus a combined Enterprise Value of around £730m (so proforma EV/EBITDA of 8x vs Breedon 10x EV/EBITDA 2021F).

Opinion Management present a good investment case suggesting that although there are much larger global concrete companies like Lafarge Holcim, there is potential for a regional business to consolidate local quarries, and also buy unwanted subsidiaries from the global players. It’s a similar strategy to Jim Ratcliffe at Ineos, who bought ICI and BP’s unwanted bits, and is now top of The Sunday Times rich list.

You might not think concrete is the most exciting industry, but Breedon Group is up 5x in the last 10 years. I’ve long believed that it is worth spending the time to understand overlooked sectors like this, or shipping (Clarkson and Ocean Wilsons) or computer games (pre pandemic). Everyone seems to have an opinion on supermarkets and banks, because they’re so familiar. Whereas concrete, well there just aren’t that many people interested in concrete. So a keen investor can create an “edge”, although it might make your conversation a bit dull at parties.

What I don’t have a feel for is i) amount of future capex that SigmaRoc requires ii) cyclical nature of the industry is. So I think if you’re prepared to take the time to understand those variables, then this could continue to do well.

Bruce Packard

Notes

The author owns shares in Burford

*The Prevalence and Validity of EBITDA as a Performance Measure A Verriest, J Bouwens, T De Kok.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.