Investors often find resilient businesses occupying specialist niches. Richard takes a first look at Sopheon PLC, which makes software that helps big businesses manage the many products they are developing, and the strategic projects they are working on.

The eye-catching thing about Sopheon is its customer base, which the company describes as a Who’s Who of the world’s leading companies:

One line of Sopeheon’s client list. Source: Sopheon.com – A selection of Our Customers.

Sopheon claims The Hershey Company, one of the largest chocolate makers in the world, Lockheed Martin, a business that has its finger in so many pies I cannot list them all, and dozens of other blue chip companies as customers.

Just to drop a few more names, in 2020, it added DuPont, LG, and Mondelez to its client list.

It is tempting to believe it is a market leader itself, but a couple of things make me question that.

Sopheon has been listed for more than two decades but it is not a big company. It makes software that addresses a number of business needs, most specifically the management of product development.

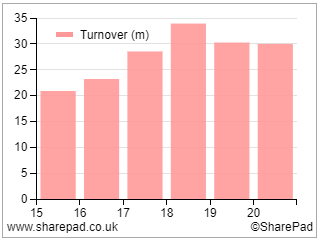

This market was worth over $3 billion in 2019 according to Gartner (a figure quoted by Sopheon in its annual report), yet Sopheon’s revenue in the same year was only $30 million.

Rivals like Planbox and HYPE Innovation and many others reel off equally impressive customer lists. While their capabilities may differ in detail, I think it is safer to assume Sopheon operates in a competitive market.

Sopheon focuses on a fairly broad range of big industries: chemicals, aerospace, consumer products, food and beverage, automotive and transportation, and high technology. It may be a market leader in some of these industries.

Helping companies innovate

Sopheon and its rivals write software that enable large businesses to manage the development of new products, a software niche known as Enterprise Innovation Management.

Its main product, Accolade, launched in 2000, follows the well-established “stage-gate” method of project management where each stage of innovation, from concept through design, trials and roll-out, ends with a decision gate at which point the organisation can choose to cancel or alter the course of the project.

It differs from project management software, where the emphasis is on scheduling individual projects through predictable stages, due to its flexibility and the fact that it is deployed across the whole business allowing companies to evaluate and compare projects on equal terms to inform strategic planning.

The company says Accolade speeds up innovation, reduces cost, and increases the probability of success.

In recent years, the company has extended its mission from helping customers automate product innovation to business model innovation, believing Accolade has the potential to be a third pillar of business software systems beside Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) and Customer Relationship Management (CRM).

History of disappointment, surges of excitement

Judging by the historical Sopheon share price, the company has a long history of underachieving investors’ no doubt often unrealistic expectations, bracketed by a short periods when it has excited them:

A few years ago it seemed as though a maturing product with a blue chip customer base was finally generating substantial profit growth.

Commentary from that time anticipated continued growth due to the recruitment of new customers as businesses seek to automate their activities and the number of big innovators using Accolade would inspire hold-outs to ditch their ad-hoc systems and become customers.

|

|

|

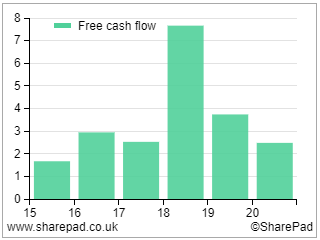

But in 2019 turnover, profit and cashflow all fell sharply, and they fell again in 2020.

In the company’s 2019 annual report, it said mergers between customers, changes in personnel at some customers, and changes in the scope of some implementations, had deferred business, reducing revenue in the short term but not the value of the sales the company ultimately expected to make.

Sopheon gave the impression that the decline in business was temporary.

It also said it was beginning the transition of its products from perpetual licenses of software shipped to customers to subscriptions to software delivered as a service over the Internet (Software as a Service or SaaS)

SaaS has many benefits for customers and software houses. It allows developers to improve the software and make the changes available to customers more quickly, it reduces the upfront cost to customers, and SaaS smooths payments providing more predictability.

It also means the supplier earns less money up front, which can lead to a fall in turnover until the value of gradually increasing recurring revenue outweighs the loss of license payments.

But SaaS was not a big factor in the company’s decline in performance in 2019. It sold fewer perpetual licenses, but not because SaaS turnover increased. The level of SaaS business was on a par with 2018.

Despite deferred business, turnover declined marginally the following year (to December 2020), along with larger declines in profit and cashflow.

This time the company highlighted the pandemic and the transition to SaaS as principal factors affecting its performance and noted that 2020 was a year of transition in which it had embarked on redeveloping its software as “cloud native” applications (i.e. served entirely over the Internet).

Figures in the income statement that help us look through the transition to SaaS and see what lies ahead may be more reassuring. The total contract value (TCV) of SaaS business in 2020, including future turnover from SaaS subscriptions, increased nearly threefold from $2.4 to $6.6 million, however it is still a small part of the business.

Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR), which includes SaaS and also services like hosting and maintenance contracts associated with perpetual licenses, increased from $15.9 million to $18 million. The balance (approximately $12 million) comes from consultancy and dwindling perpetual license sales.

All change

Acquisitions, which have been quietly mooted in previous years without any deals being done, appear to have moved up the list of strategic priorities. The company now promises to move fast when the opportunity arises.

It is also adopting a low-cost high-volume sales model. It’s hoping to attract innovation professionals in organisations to adopt its new cloud-based software, and use that relationship to sell the enterprise features.

Accompanying these strategic shifts are changes in the board. Founder Barry Mence has stepped down as chairman, though he remains a non-executive director. Andrew Michuda, who had been chief executive since 2000 is now executive chairman. Greg Coticchia, who joined in October last year, is the new chief executive. There is a new finance director too.

It seems everything is changing at Sopheon. The product’s scope, the underlying technology and delivery, and how it is sold, and the strategy which as well as putting greater emphasis on acquisitions is also elevating the role of resellers which have traditionally taken a back seat to direct sales.

No doubt change has been thrust on the company by circumstances, the shifting of software to the cloud is affecting all software companies, and Sopheon sees these changes as an opportunity.

To my inexpert mind though, Sopheon has been slow to grasp that opportunity and aspects of the evolving strategy are not necessarily cohesive. For example, I wonder if selling low-cost products will be fruitful. Accolade is designed to be deployed across an enterprise, so appealing to individual professionals may not work if their roles are not strategic.

The prospect of acquisitions also adds risk, and the need to acquire new capabilities may be an admission that the product is not that special, though it may once have been.

I wonder about the stage-gate methodology, which emerged from processes developed in the 1950s, and how relevant it will be in an age when the development of software products has been revolutionised by another process: Agile (see Alistair Blair’s article on Kainos for a good description of Agile).

As you might expect, advocates of the older system including Sopheon are moving with the times by co-opting Agile, and advocating a “best of both” methodology.

Researching Sopheon has reminded me of how competitive the software industry is, and how difficult it is to work out which businesses should win.

In particular, niches seem like much less secure places than in other industries.

The endemic disruption in software that Sopheon is hoping to take advantage of, could undermine its own business. It faces challenges not just from direct rivals, but newer, dare I say agile, competitors, and software companies seeking to extend the feature sets of products that currently do not compete directly with Accolade.

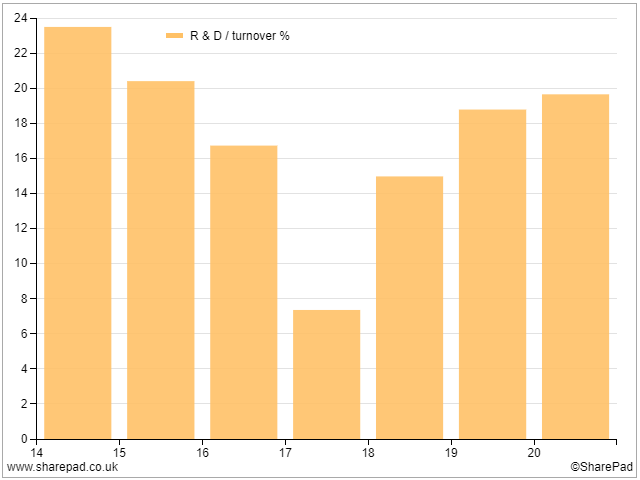

Sopheon is investing furiously to stay relevant, perhaps depressing profits in the short term, but I have not yet established what makes Accolade unique or special, and therefore why we can expect it to win.

Worryingly, I have just read Bruce’s critical write up of D4t4, a software company in another niche that I have written up and subsequently invested in despite the pandemic. Bruce highlighted its transition to SaaS, heavy investment, and now wholesale changes to the board.

D4t4, though, strongly asserts the unique and patented features of its product, Celebrus. That may give me the confidence to ride out the uncertainty.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard