This week, Jamie talks about two types of equity investment those which should be held with the intention of an indefinite horizon and those that are expected to be sold. He then compares three companies, two of which he thinks should be long term holds and the other one only to be traded.

The commentary last week from various Federal Reserve members and the like implied inflation may not continue its downward trajectory. The reaction in the bond markets was pretty rational with a fairly widespread, albeit modest, sell off. The reaction in equity markets made a little less sense however as the US mega-cap ‘growth’ stocks having a particularly good week. Such is the vastness of some of the largest technology names today, in five trading days NVidia increased in value by >$150b or one and a quarter entire Unilevers on essentially no news.

There are at least two ways to approach equity investment. The first is when you buy something believing it likely to go up in price so that it can be sold. The second is when you buy something that you think will become more and more valuable over time – often without a plan to sell at all.

In an institutional setting, the former takes a few names, but the most common are value investing and special situations. These are often investments in businesses where the underlying company is in distress, which has caused the valuation to be at odds with a sensible assessment of worth. Frequently, these businesses operate in cyclical industries so that there are prolonged periods of depressed earnings. Investing in these businesses is done so on the proviso that good times are ahead. However, because of the cyclical nature of the industry, those good times will be temporary, just as is the case in the periods of distress. Occasionally, you will hear the phrase ‘it is a rent, not own type of stock’. It’s a slightly odd term of phrase because, of course, you do actually own the stock. In this case the rent refers to the ephemeral nature of your ownership.

The counter point to these sorts of businesses is when you buy with the intention of enjoying the effects of compounding. These typically take the form of companies that are less cyclical, or even not at all cyclical. They are growing, sometimes only sedately; and are of reasonable quality (see last week’s article for more on quality). Institutionally, these sorts of businesses are categorised with terms like defensive investing, growth investing or quality investing. These phrases aren’t mutually exclusive insofar as it is possible to be a defensive quality investment etc. These are the types of business you own. But this time, the phrase own has an unlimited meaning. Note: unlimited here does not mean permanent, it means that the ownership has no set end. Should the circumstances of the business change or the valuation become extreme, a stock in the own category can and should be sold. This is an important point; a great deal of capital can be lost by falling in love with a stock.

In reality, the best types of investments contain elements of both the rent and own category. Warren Buffett has said in the past that, as an investor, he is 85% Benjamin Graham and 15% Phillip Fisher. Benjamin Graham wrote the Intelligent Investor and is considered the godfather of value investing. Phillip Fisher wrote Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and is about the tremendous returns available if you invest in businesses that become more valuable over decades. I’ve often wondered whether Mr Buffett tilts 85% in favour of Mr Graham in reverence of his former employer, after whom, along with his father Howard, his first-born son is named. If you read The Snowball* by Alice Schroeder, it seems more likely that the ratios should be reversed and indeed he believes far more success can be enjoyed by sitting tight on compounding machines – to own if you will.

*I wouldn’t recommend The Snowball as a read. It is perfectly well written but once you get past about 1974, it becomes rather samey.

Ultimately, then there is no best type of investment but if you can find those situations where there are elements of all the best bits, you have a good chance of making great returns. That is to say, and I’m aware this is not exactly ground breaking, but the sweet spot of investment lies at the intersection of good and cheap.

As for Mr Buffett, a great example of how to and how not to it can be found in the same investment, Coca-Cola. To counteract the then surging competition of Pepsi and its famous Pepsi Challenge advertisement, Coca-Cola was disastrously relaunched as New Coke in 1985. It was badly received and the subsequent blowback saw earnings fall significantly, and with it the valuation of Coca-Cola. In 1988, the share price was at a very low level and Mr Buffett made one of his greatest ever investments; buying almost 10% of the whole business for what proved to be a steal. Unfortunately for Buffett, he fell in love with the stock. In the late 1990s, Coca-Cola had regained so much of its lustre that it was now a stock market darling that the valuation had moved to extremes in the other way. What followed was a painful lesson as the share price proceeded to half in the next decade with Buffett’s stake untouched through the period.

This week I talk about Renishaw and DCC, both of whom could be in the sweet spot as businesses that are both good and cheap. I then talk about a stock that is merely cheap – Barratt Development.

Renishaw, Half Year report

History

History

Renishaw was founded in the early 70s by David McMurtry and John Deer when the former invented a touch probe whilst working at Rolls-Royce on aero engines. The touch probe allowed for very precise measurements on components used in jet engines. It fully listed in 1984 and has steadily grown through innovation since.

The founders are now over 80 but still involved with the business. McMurtry is executive chairman and owns 36% of the equity of the business. For those of you who are interested in cars, he has a side project in extreme performance cars. His other business, McMurtry Automotive built the Spéirling (named for an old Irish word meaning violence). It is a tiny electric hyper car that uses fans to suck the car to the tarmac. It is the current holder of the Goodwood Festival of Speed hill climb record. I mention this in passing but I think it speaks to the passion of Sir David. The fact he retains executive responsibilities despite being chairman means it falls foul of certain governance norms, but personally I rather like his continued involvement. John Deer is a non-executive deputy chairman who owns just over 16% of the equity. Taken as a block therefore, Sir David and Mr Deer having effective control over the business since their combined holding is more than 50%.

The actual day-to-day running of the business is done by Will Lee, who was appointed CEO in 2018 having joined Renishaw as a graduate trainee in the mid-90s. The finance director, Allen Roberts has been in the role for 43 years; one assumes he is amongst the longest executive appointments in the UK (other than Sir David of course).

Today, Renishaw is involved in areas for which very high levels of precision and accuracy is required. Divisionally, it is split between ‘Manufacturing’, ‘Medical & Healthcare’ and ‘Scientific, Research & Analysis’. There are numerous subdivisions and if you are interested you can spend hours looking through the website at the various solutions it creates. The highlights for me include Additive Manufacturing (what used to be called 3D printing) and Neurosurgery Products & Systems. Neither are big earners for the company (yet) but give a flavour for the very high levels of technical expertise contained within the business.

Half Year Figures

It has been a rough few years for Renishaw. The company has notoriously short visibility on its earnings since much of its products plug in to the capital cycle and sales can fall quite quickly when economic conditions are disadvantageous. The economic environment has been, and remains, mixed at best. For the most recent figures, the company sales fell -5% in reported terms with the decline moderated to just -2% on constant currency basis. By mix, Asia geographically and both the analytical and medical divisionally are doing very well. This was more than offset however by a moderate decline in the much larger manufacturing led business.

Operational gearing is such that, despite cost controls, profits before tax fell 27% on a reported basis and 23% when adjusted for certain non-repeating items. One thing to really like about Renishaw is its ability to weather tricky conditions on account of an always very strong balance sheet. Cash declined slightly as capital expenditure (i.e., what drives future growth) and dividends outweighed the cash flow from operations but, at >£180m, it still represents an entire year of EBITDA. It is worth noting also that the company has very few leases because it owns outright the freehold on much of its asset base.

In its outlook statement there is a standard statement that the end markets are cyclical but in the long-term (which is what matters to a business owner), the company is capable of high single digit organic growth on a through-the-cycle basis. Management have given revenue and profit guidance figures that have a fairly wide range and are someway below the levels from a few years ago

Opinion & Valuation

Whether he would agree or not, Sir David is a maverick. Importantly he is a maverick in a very good way. Too often corporate strategy, particularly in the UK, is towards short termism; what costs can be cut? how can margins be boosted? is the balance sheet efficient? Renishaw does, and always has been dedicated to long-term value generation, excellence in its products and services and, most admirably of all, a large proportion of the important innovation and manufacturing being done in the UK.

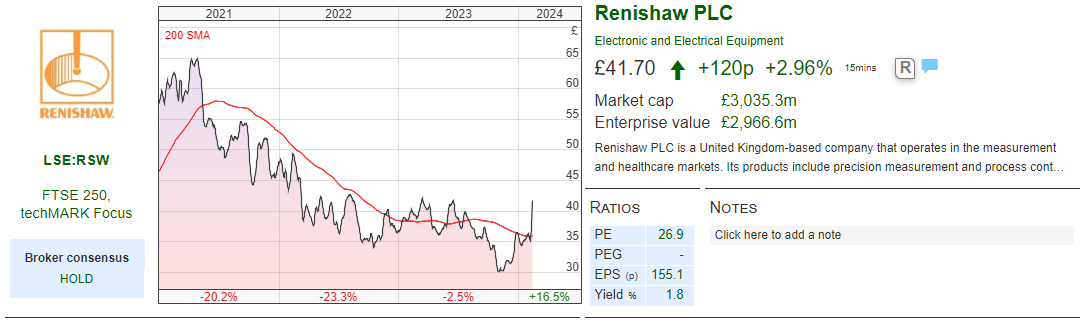

Renishaw is a truly excellent business and very rare to see in the UK. Should the long-term organic growth expectations be accurate (i.e., growth not generated through acquisition), then you could argue for an extremely high valuation since the Gordon Growth Model would yield a very small denominator in the formula, which reverses to a very high-earnings multiple. The capital employed figure of c. £1b combined with a ROCE of between 20% and 25% on a through the cycle basis yields a normalised EBIT of between £200m and £250m. Note, EBIT is currently some way below this.

One of the reasons that so few high-quality businesses don’t list in the UK is that the investor base is unwilling to value high growth, quality businesses commensurate with the long-term value creation potential. As a UK listed business, the company typically sits around 15x it’s normalised EBIT figure. Taking the mid-point of the figures I gave that gives an enterprise value of £3,375m, which translates to c. £3,500m market cap. That represents 16% upside from here or c. £48 per share. This rather misses the point; taking two US listed entities of equivalent quality as examples:

- Intuitive Surgical, which is probably better even than Renishaw with its near global monopoly on surgical robots – one of Intuitive’s only credible global competitors is, erm, Renishaw as it happens. It currently trades on an EV/EBIT of c. 75x.

- Waters, which makes all sorts of clever machinery involved in molecular analysis – adjacent to another part of Renishaw; currently trades on an EV/EBIT of c. 25x.

Even in Europe, Hexagon AB, another business with adjacencies and overlap with Renishaw’s business lines, trades at a multiple > 20x. If Renishaw traded anywhere near any of these company’s multiples, it would have to be considerably more expensive than today.

Two and half years ago, Sir David announced that he would like to sell Renishaw. The subsequent excitement around one of the best businesses in the UK becoming available, saw the shares peak >£65 with a high valuation to boot. Sir David however is not interested in extracting every last penny from the valuation – he is already as rich as Croesus. Rather he has a legacy to consider. That is the legacy of the creator of one of the most innovative businesses in the UK, which is a bright spot in British excellence in manufacturing.

One day, the business probably will get taken over. I as a shareholder will benefit, but personally shall mourn the disappearance of another great British business. Renishaw very much sits in the own not rent part of the equation, though arguably, even following the sharp rise in the share price post the release of the figures, the company might even be in the sweet spot regarding valuation too.

DCC, Third quarter interim management statement

History

History

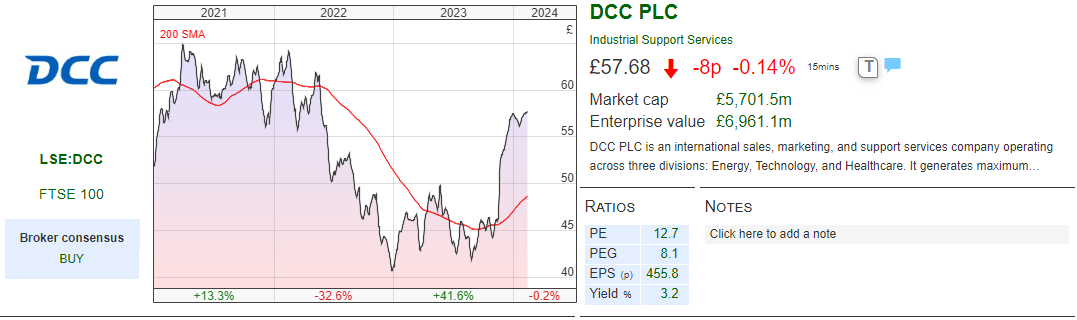

I talked about DCC three months ago at the time of the half year figures where I gave a longer summary of the history of the business. In brief, DCC stands for Development Capital Corporation and is involved in the acquisition of businesses that address long-term strategic growth areas. It is an Irish incorporated business with interests in technology fulfilment, medical distribution but most notably in energy. Historically, the energy business was most concerned with distributing oil and gas but is increasingly focused on energy transition and renewables.

Third Quarter Update

At the last update, the shares were up sharply but had been in the doldrums for a while beforehand. I posited that the reason was because for a number of years the company hadn’t been executing on its acquisition strategy sufficiently well for many in the market. My own belief was that the company had withdrawn temporarily from its roll up strategy owing to high valuations being attached to its target market of private enterprises. This was a good thing in my view since it spoke to a discipline in acquisitions that is too frequently forgotten by others. The half year figures provided insight into new impetus to the strategy as the company continued to execute on its pivot towards businesses that help facilitate energy transition.

Since then, the shares, have risen a further 10% prior to last week’s update. In brief, things are in line, the mild winter we’ve enjoyed wasn’t helpful, but the company’s bottom line was seemingly unaffected. More importantly, the company provided an update on the strategic investments. It has been a relatively slow quarter for transaction with just £45m committed compared £310m for the first six months. This additional £45m in commitments was made of one large acquisition and several bolt-ons. The large acquisition was for a company that ‘provides energy management services including energy procurement, market analysis, risk management and net zero pathway consulting to industrial, commercial, and public sector customers in the UK’. That is to say a business that is complementary to the emerging renewable energy part of the group. The few bolt-ons were for renewable fuels distributors with a geographic footprint including the UK, Ireland and Austria.

Opinion & Valuation

For the previous update, I suggested the EV/EBIT of 10x that it was trading on at the time, was low and a figure closer to 13x was more in line with the long-term levels. Since then, the valuation has moved slightly higher to around 11x in line with the increase in the share price. This still looks to be very good value for a company that has proved to be an outstanding long-term steward of capital. In other words, this, like Renishaw is very much an own situation that is also usefully cheap at current levels. I’m unconcerned by the c. 30% rise in the last few months as I can still see plenty of potential from here.

Barratt Development, Half Year Figures

Half Year Update

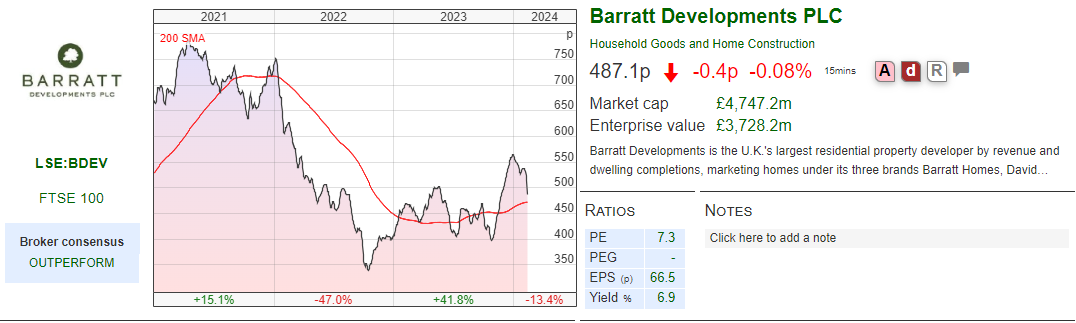

The house building sector in the UK is really struggling at present and Barratt, despite being one of the larger, more diverse and better capitalised businesses is no exception. Home completions in the six months were 6,171 representing a fall of 28.5% on the previous year. Revenue fell 33.5% demonstrating that as well as volumes declining sharply, average transaction values also fell. Fortunately, housebuilders generate most of their costs in the gross line and thus, even a sharp decline like the one witnessed still saw the business generating a profit (however meagre). Overall, profit before tax fell 81% and 70% on an adjusted basis.

With housebuilding being badly burnt in the financial crisis of the late 2000s, they now operate with much stronger balance sheets than before. Consequently, net cash, even after a >£200m decline was still at a healthy £750m. Elsewhere, the dividend was halved in order to better reflect the reality of the economic environment in which the sector is operating and TNAV declined modestly on the cash reduction.

Separately, the company announced an all share offer for the equity of smaller rival Redrow. It is difficult to see how, in the terms of the deal, either set of shareholders benefits more or less than the other. Ultimately, these companies face the same economic reality – tie two dead birds together, they may have four wings, but still, they cannot fly. Alright these birds are wounded, not dead but the point is that the merger doesn’t really change anything.

Opinion

The ROCE is report as having been c. 30% for much of the last few years. Frankly this is massively inflated by a mixture of rock bottom interest rates and quantitative easing, the help-to-buy scheme (which ought to have been called help-to-sell really), and cheaper labour than historically owing to higher levels of immigration from poorer countries. Imagine training as a brickie in the 90s thinking you would have a career of skilled labour that would afford you a reasonable lifestyle only to see your standard of living crushed by a collapse in day rates.

On a through-the-cycle basis, a competently managed housebuilder ought to make mid-teens ROCE. The fact that the sector has spent so long earning well above this rate may well portend to a period of considerably weaker earnings. The valuation implies that, at best, Barratt will not create any value for the foreseeable future – my fear is that even this may be optimistic. There are times to buy housebuilders but it is usually when the price to book is well below 1x. And even then, ironically, they are a stock you rent not own.

Jamie Ward

Jamie owns shares in Renishaw and DCC

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Weekly Market Commentary | 13/02/2024 | RSW, DCC, BDEV | Rent vs. Own

This week, Jamie talks about two types of equity investment those which should be held with the intention of an indefinite horizon and those that are expected to be sold. He then compares three companies, two of which he thinks should be long term holds and the other one only to be traded.

The commentary last week from various Federal Reserve members and the like implied inflation may not continue its downward trajectory. The reaction in the bond markets was pretty rational with a fairly widespread, albeit modest, sell off. The reaction in equity markets made a little less sense however as the US mega-cap ‘growth’ stocks having a particularly good week. Such is the vastness of some of the largest technology names today, in five trading days NVidia increased in value by >$150b or one and a quarter entire Unilevers on essentially no news.

There are at least two ways to approach equity investment. The first is when you buy something believing it likely to go up in price so that it can be sold. The second is when you buy something that you think will become more and more valuable over time – often without a plan to sell at all.

In an institutional setting, the former takes a few names, but the most common are value investing and special situations. These are often investments in businesses where the underlying company is in distress, which has caused the valuation to be at odds with a sensible assessment of worth. Frequently, these businesses operate in cyclical industries so that there are prolonged periods of depressed earnings. Investing in these businesses is done so on the proviso that good times are ahead. However, because of the cyclical nature of the industry, those good times will be temporary, just as is the case in the periods of distress. Occasionally, you will hear the phrase ‘it is a rent, not own type of stock’. It’s a slightly odd term of phrase because, of course, you do actually own the stock. In this case the rent refers to the ephemeral nature of your ownership.

The counter point to these sorts of businesses is when you buy with the intention of enjoying the effects of compounding. These typically take the form of companies that are less cyclical, or even not at all cyclical. They are growing, sometimes only sedately; and are of reasonable quality (see last week’s article for more on quality). Institutionally, these sorts of businesses are categorised with terms like defensive investing, growth investing or quality investing. These phrases aren’t mutually exclusive insofar as it is possible to be a defensive quality investment etc. These are the types of business you own. But this time, the phrase own has an unlimited meaning. Note: unlimited here does not mean permanent, it means that the ownership has no set end. Should the circumstances of the business change or the valuation become extreme, a stock in the own category can and should be sold. This is an important point; a great deal of capital can be lost by falling in love with a stock.

In reality, the best types of investments contain elements of both the rent and own category. Warren Buffett has said in the past that, as an investor, he is 85% Benjamin Graham and 15% Phillip Fisher. Benjamin Graham wrote the Intelligent Investor and is considered the godfather of value investing. Phillip Fisher wrote Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and is about the tremendous returns available if you invest in businesses that become more valuable over decades. I’ve often wondered whether Mr Buffett tilts 85% in favour of Mr Graham in reverence of his former employer, after whom, along with his father Howard, his first-born son is named. If you read The Snowball* by Alice Schroeder, it seems more likely that the ratios should be reversed and indeed he believes far more success can be enjoyed by sitting tight on compounding machines – to own if you will.

*I wouldn’t recommend The Snowball as a read. It is perfectly well written but once you get past about 1974, it becomes rather samey.

Ultimately, then there is no best type of investment but if you can find those situations where there are elements of all the best bits, you have a good chance of making great returns. That is to say, and I’m aware this is not exactly ground breaking, but the sweet spot of investment lies at the intersection of good and cheap.

As for Mr Buffett, a great example of how to and how not to it can be found in the same investment, Coca-Cola. To counteract the then surging competition of Pepsi and its famous Pepsi Challenge advertisement, Coca-Cola was disastrously relaunched as New Coke in 1985. It was badly received and the subsequent blowback saw earnings fall significantly, and with it the valuation of Coca-Cola. In 1988, the share price was at a very low level and Mr Buffett made one of his greatest ever investments; buying almost 10% of the whole business for what proved to be a steal. Unfortunately for Buffett, he fell in love with the stock. In the late 1990s, Coca-Cola had regained so much of its lustre that it was now a stock market darling that the valuation had moved to extremes in the other way. What followed was a painful lesson as the share price proceeded to half in the next decade with Buffett’s stake untouched through the period.

This week I talk about Renishaw and DCC, both of whom could be in the sweet spot as businesses that are both good and cheap. I then talk about a stock that is merely cheap – Barratt Development.

Renishaw, Half Year report

Renishaw was founded in the early 70s by David McMurtry and John Deer when the former invented a touch probe whilst working at Rolls-Royce on aero engines. The touch probe allowed for very precise measurements on components used in jet engines. It fully listed in 1984 and has steadily grown through innovation since.

The founders are now over 80 but still involved with the business. McMurtry is executive chairman and owns 36% of the equity of the business. For those of you who are interested in cars, he has a side project in extreme performance cars. His other business, McMurtry Automotive built the Spéirling (named for an old Irish word meaning violence). It is a tiny electric hyper car that uses fans to suck the car to the tarmac. It is the current holder of the Goodwood Festival of Speed hill climb record. I mention this in passing but I think it speaks to the passion of Sir David. The fact he retains executive responsibilities despite being chairman means it falls foul of certain governance norms, but personally I rather like his continued involvement. John Deer is a non-executive deputy chairman who owns just over 16% of the equity. Taken as a block therefore, Sir David and Mr Deer having effective control over the business since their combined holding is more than 50%.

The actual day-to-day running of the business is done by Will Lee, who was appointed CEO in 2018 having joined Renishaw as a graduate trainee in the mid-90s. The finance director, Allen Roberts has been in the role for 43 years; one assumes he is amongst the longest executive appointments in the UK (other than Sir David of course).

Today, Renishaw is involved in areas for which very high levels of precision and accuracy is required. Divisionally, it is split between ‘Manufacturing’, ‘Medical & Healthcare’ and ‘Scientific, Research & Analysis’. There are numerous subdivisions and if you are interested you can spend hours looking through the website at the various solutions it creates. The highlights for me include Additive Manufacturing (what used to be called 3D printing) and Neurosurgery Products & Systems. Neither are big earners for the company (yet) but give a flavour for the very high levels of technical expertise contained within the business.

Half Year Figures

It has been a rough few years for Renishaw. The company has notoriously short visibility on its earnings since much of its products plug in to the capital cycle and sales can fall quite quickly when economic conditions are disadvantageous. The economic environment has been, and remains, mixed at best. For the most recent figures, the company sales fell -5% in reported terms with the decline moderated to just -2% on constant currency basis. By mix, Asia geographically and both the analytical and medical divisionally are doing very well. This was more than offset however by a moderate decline in the much larger manufacturing led business.

Operational gearing is such that, despite cost controls, profits before tax fell 27% on a reported basis and 23% when adjusted for certain non-repeating items. One thing to really like about Renishaw is its ability to weather tricky conditions on account of an always very strong balance sheet. Cash declined slightly as capital expenditure (i.e., what drives future growth) and dividends outweighed the cash flow from operations but, at >£180m, it still represents an entire year of EBITDA. It is worth noting also that the company has very few leases because it owns outright the freehold on much of its asset base.

In its outlook statement there is a standard statement that the end markets are cyclical but in the long-term (which is what matters to a business owner), the company is capable of high single digit organic growth on a through-the-cycle basis. Management have given revenue and profit guidance figures that have a fairly wide range and are someway below the levels from a few years ago

Opinion & Valuation

Whether he would agree or not, Sir David is a maverick. Importantly he is a maverick in a very good way. Too often corporate strategy, particularly in the UK, is towards short termism; what costs can be cut? how can margins be boosted? is the balance sheet efficient? Renishaw does, and always has been dedicated to long-term value generation, excellence in its products and services and, most admirably of all, a large proportion of the important innovation and manufacturing being done in the UK.

Renishaw is a truly excellent business and very rare to see in the UK. Should the long-term organic growth expectations be accurate (i.e., growth not generated through acquisition), then you could argue for an extremely high valuation since the Gordon Growth Model would yield a very small denominator in the formula, which reverses to a very high-earnings multiple. The capital employed figure of c. £1b combined with a ROCE of between 20% and 25% on a through the cycle basis yields a normalised EBIT of between £200m and £250m. Note, EBIT is currently some way below this.

One of the reasons that so few high-quality businesses don’t list in the UK is that the investor base is unwilling to value high growth, quality businesses commensurate with the long-term value creation potential. As a UK listed business, the company typically sits around 15x it’s normalised EBIT figure. Taking the mid-point of the figures I gave that gives an enterprise value of £3,375m, which translates to c. £3,500m market cap. That represents 16% upside from here or c. £48 per share. This rather misses the point; taking two US listed entities of equivalent quality as examples:

Even in Europe, Hexagon AB, another business with adjacencies and overlap with Renishaw’s business lines, trades at a multiple > 20x. If Renishaw traded anywhere near any of these company’s multiples, it would have to be considerably more expensive than today.

Two and half years ago, Sir David announced that he would like to sell Renishaw. The subsequent excitement around one of the best businesses in the UK becoming available, saw the shares peak >£65 with a high valuation to boot. Sir David however is not interested in extracting every last penny from the valuation – he is already as rich as Croesus. Rather he has a legacy to consider. That is the legacy of the creator of one of the most innovative businesses in the UK, which is a bright spot in British excellence in manufacturing.

One day, the business probably will get taken over. I as a shareholder will benefit, but personally shall mourn the disappearance of another great British business. Renishaw very much sits in the own not rent part of the equation, though arguably, even following the sharp rise in the share price post the release of the figures, the company might even be in the sweet spot regarding valuation too.

DCC, Third quarter interim management statement

I talked about DCC three months ago at the time of the half year figures where I gave a longer summary of the history of the business. In brief, DCC stands for Development Capital Corporation and is involved in the acquisition of businesses that address long-term strategic growth areas. It is an Irish incorporated business with interests in technology fulfilment, medical distribution but most notably in energy. Historically, the energy business was most concerned with distributing oil and gas but is increasingly focused on energy transition and renewables.

Third Quarter Update

At the last update, the shares were up sharply but had been in the doldrums for a while beforehand. I posited that the reason was because for a number of years the company hadn’t been executing on its acquisition strategy sufficiently well for many in the market. My own belief was that the company had withdrawn temporarily from its roll up strategy owing to high valuations being attached to its target market of private enterprises. This was a good thing in my view since it spoke to a discipline in acquisitions that is too frequently forgotten by others. The half year figures provided insight into new impetus to the strategy as the company continued to execute on its pivot towards businesses that help facilitate energy transition.

Since then, the shares, have risen a further 10% prior to last week’s update. In brief, things are in line, the mild winter we’ve enjoyed wasn’t helpful, but the company’s bottom line was seemingly unaffected. More importantly, the company provided an update on the strategic investments. It has been a relatively slow quarter for transaction with just £45m committed compared £310m for the first six months. This additional £45m in commitments was made of one large acquisition and several bolt-ons. The large acquisition was for a company that ‘provides energy management services including energy procurement, market analysis, risk management and net zero pathway consulting to industrial, commercial, and public sector customers in the UK’. That is to say a business that is complementary to the emerging renewable energy part of the group. The few bolt-ons were for renewable fuels distributors with a geographic footprint including the UK, Ireland and Austria.

Opinion & Valuation

For the previous update, I suggested the EV/EBIT of 10x that it was trading on at the time, was low and a figure closer to 13x was more in line with the long-term levels. Since then, the valuation has moved slightly higher to around 11x in line with the increase in the share price. This still looks to be very good value for a company that has proved to be an outstanding long-term steward of capital. In other words, this, like Renishaw is very much an own situation that is also usefully cheap at current levels. I’m unconcerned by the c. 30% rise in the last few months as I can still see plenty of potential from here.

Barratt Development, Half Year Figures

Half Year Update

The house building sector in the UK is really struggling at present and Barratt, despite being one of the larger, more diverse and better capitalised businesses is no exception. Home completions in the six months were 6,171 representing a fall of 28.5% on the previous year. Revenue fell 33.5% demonstrating that as well as volumes declining sharply, average transaction values also fell. Fortunately, housebuilders generate most of their costs in the gross line and thus, even a sharp decline like the one witnessed still saw the business generating a profit (however meagre). Overall, profit before tax fell 81% and 70% on an adjusted basis.

With housebuilding being badly burnt in the financial crisis of the late 2000s, they now operate with much stronger balance sheets than before. Consequently, net cash, even after a >£200m decline was still at a healthy £750m. Elsewhere, the dividend was halved in order to better reflect the reality of the economic environment in which the sector is operating and TNAV declined modestly on the cash reduction.

Separately, the company announced an all share offer for the equity of smaller rival Redrow. It is difficult to see how, in the terms of the deal, either set of shareholders benefits more or less than the other. Ultimately, these companies face the same economic reality – tie two dead birds together, they may have four wings, but still, they cannot fly. Alright these birds are wounded, not dead but the point is that the merger doesn’t really change anything.

Opinion

The ROCE is report as having been c. 30% for much of the last few years. Frankly this is massively inflated by a mixture of rock bottom interest rates and quantitative easing, the help-to-buy scheme (which ought to have been called help-to-sell really), and cheaper labour than historically owing to higher levels of immigration from poorer countries. Imagine training as a brickie in the 90s thinking you would have a career of skilled labour that would afford you a reasonable lifestyle only to see your standard of living crushed by a collapse in day rates.

On a through-the-cycle basis, a competently managed housebuilder ought to make mid-teens ROCE. The fact that the sector has spent so long earning well above this rate may well portend to a period of considerably weaker earnings. The valuation implies that, at best, Barratt will not create any value for the foreseeable future – my fear is that even this may be optimistic. There are times to buy housebuilders but it is usually when the price to book is well below 1x. And even then, ironically, they are a stock you rent not own.

Jamie Ward

Jamie owns shares in Renishaw and DCC

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.