Fashion website Sosandar plans to open shops to bolster its sales and margins. Maynard Paton weighs up management’s bold financial ambition against the wider sector’s haphazard progress.

Fashion website Sosandar provides a fascinating dilemma for small-cap growth investors.

Bulls will highlight the online retailer’s very rapid expansion and bold ambition to raise profits to £10 million which, if achieved, would make its £37 million market cap extremely attractive. The story is also backed by keen co-founders and net cash.

Bears will note the £10 million profit ambition is based upon creating a chain of shops alongside continuing to sell clothes online. Sosandar’s website currently makes little profit and the fashion industry — whether selling online or through shops — is blighted by poor economics.

Let’s take a closer look.

Introducing Sosandar

“Coming back to work [after maternity leave], I didn’t want to suddenly dress in a ‘mumsy’ way, but I struggled to find things that weren’t really short, or anything that had a sleeve.

I realised that the fashion industry is obsessed with millennials, and there was a gap for clothes for women who’d graduated from younger brands, but were still fashionable and sexy.

At that time, I was editing Look, the fashion magazine I’d launched, working with the publishing director, Julie Lavington. We were asked by retailers to design clothing under the magazine’s name. I knew then that we could do this ourselves.

Julie and I went for dinner and by the time we’d left the restaurant we’d got a to-do list to launch our own clothing line, targeting women in their mid-30s and over.”

So recounted Alison Hall during this interview about why she and magazine colleague Julie Lavington left their publishing venture to establish fashion website Sosandar during 2015.

The pair’s ‘to-do’ list included designing the initial clothing range, recruiting suppliers, appointing a logistics outsourcer and of course building a website…

…which was all completed by September 2016. The business then registered its first transaction — the purchase of a leopard-print shirt dress — within five minutes after the website’s launch.

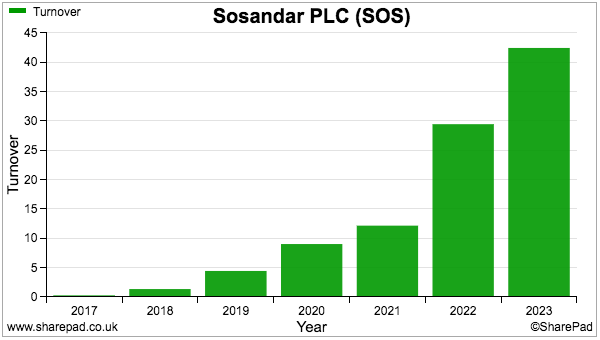

The immediate sale suggested there was indeed a gap in the market for women in their mid-30s and over who did not want to dress in a ‘mumsy’ way. Sales during the first eleven months of operation reached £487,000, and last year topped £42 million:

Hall and Lavington put their publishing skills to good use by driving early sales through persuasive emails, glossy brochures and PR press coverage. Social-media campaigns, celebrity endorsements and television advertising — alongside selling items through Next and Marks & Spencer — have all since helped turbo-charge additional revenue.

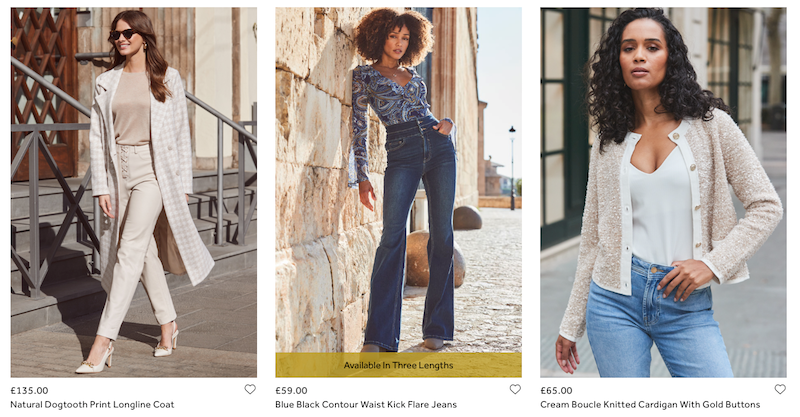

At the last count, Sosandar boasted 256,312 active customers that spend an average £99.26 per order. The clothes are predominantly designed in house and typical purchases might include:

- A natural dogtooth-print longline coat for £135;

- Blue/black contour-waist kick-flare jeans for £59, and;

- A cream boucle-knitted cardigan with gold buttons for £65.

Customers can also pay £8 a year for free UK delivery with no minimum order value.

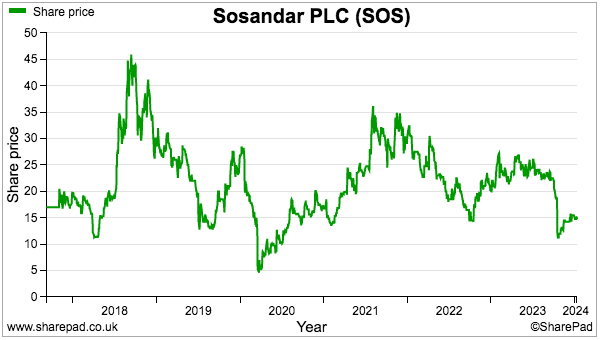

The shares joined AIM at 15p in 2017 through a reverse takeover of a failed gold explorer. More than six years on and the shares continue to trade at 15p:

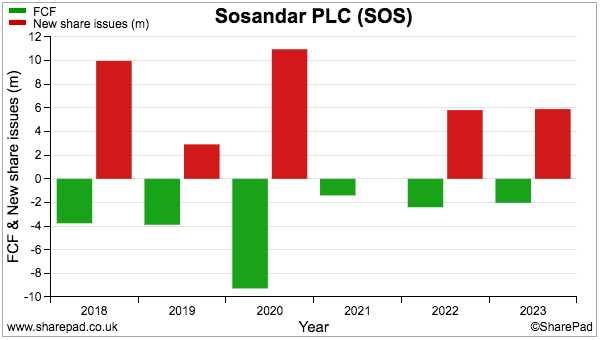

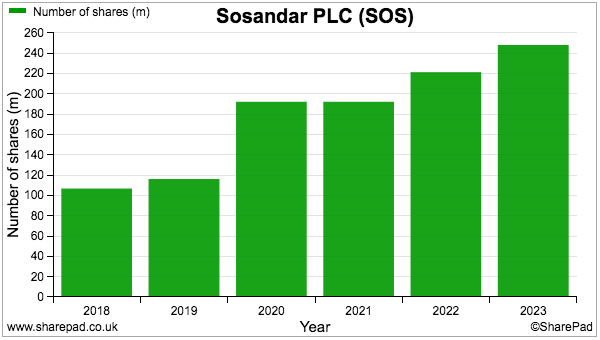

The lack of capital gains reflects Sosandar’s need for extra equity to fund the company’s initial losses and significant investment in clothing stock:

The flotation raised £10 million and a further five cash calls have since been conducted:

- October 2018: approximately £3m raised at 32p;

- July 2019: approximately £7m raised at 15p;

- February 2020: approximately £5m raised at 17p;

- May 2021: approximately £6m raised at 20p, and;

- February 2023: approximately £6m raised at 22p.

Net cash is now £8 million, but the share count has more than doubled following the flotation:

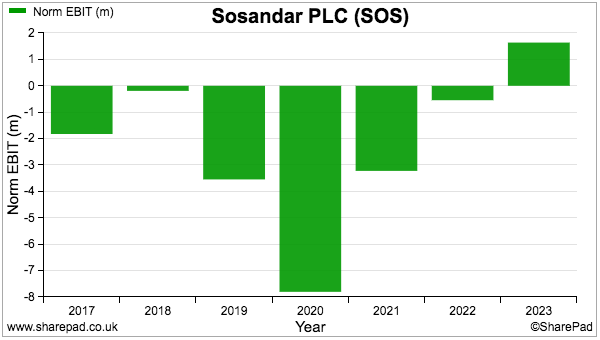

With online sales having surged, the obvious question is why now bother with opening shops… especially after the business registered its maiden profit last year?

From online-only to omni-channel

Sosandar announced the plan to open its own shops in October:

“The Company carefully monitors consumer shopping habits and trends on an ongoing basis. With clear evidence of consumers increasingly shopping on the high street coupled with the growing strength of the Sosandar brand, the Company is perfectly placed to develop its omni-channel strategy with its own bricks and mortar presence.”

Sosandar noted 60% of UK clothing sales are purchased in person, and starting a retail chain would lead to “increased brand awareness, higher margins, more efficient marketing and overall lower returns rates”.

Management provided more details during last month’s interims. This webinar talked of up to 50 outlets being targeted within affluent market towns and city centres over the “mid-to-long-term“, with units aiming to become profitable after two years and achieving full payback after three.

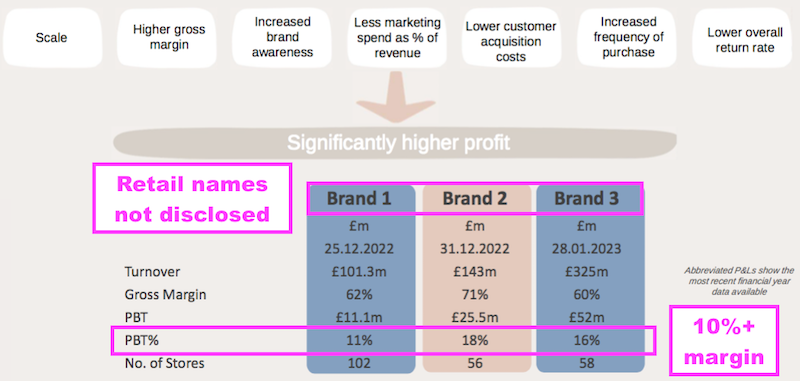

Tempting shareholders with the shop-strategy potential, Sosandar unveiled a tantalising “medium-term” ambition of targeting £100 million-plus revenue and a pre-tax profit margin of at least 10%.

December’s powerpoint included this slide to underpin the 10% or more margin assumption:

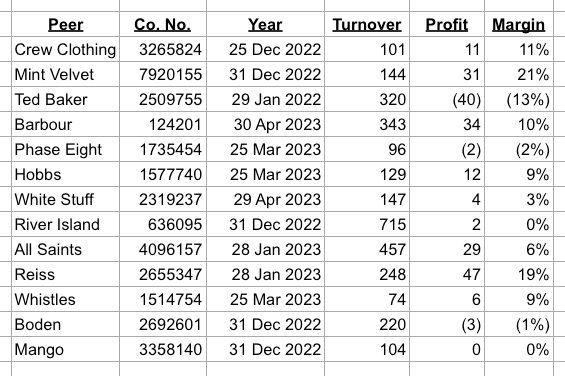

Although Sosandar did not identify the rival brands already enjoying 10%-plus margins, a number of peers were helpfully named on another slide:

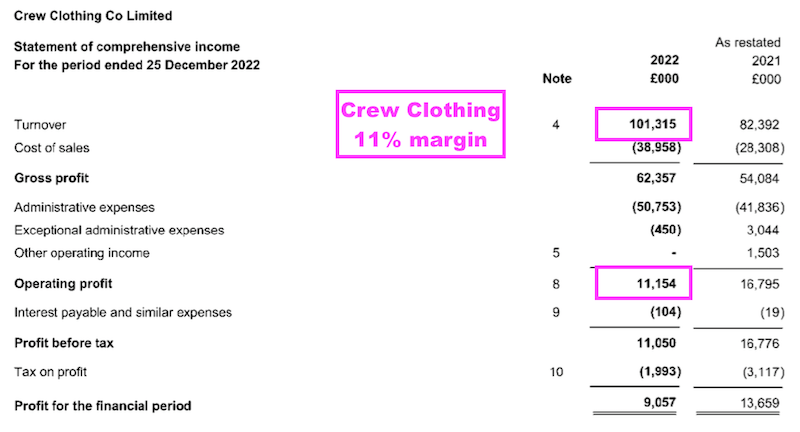

Sleuthing on Companies House revealed Brand 1 to be Crew Clothing Company:

Brands 2 and 3 sadly could not be identified among those other named peers.

Note that Crew Clothing may not be a strict like-for-like comparison with Sosandar, given the former sells menswear, childrenswear, sportswear as well as ladieswear. But Crew Clothing has sustained a double-digit margin since 2019 following its purchase by retail entrepreneur Menoshi Shina.

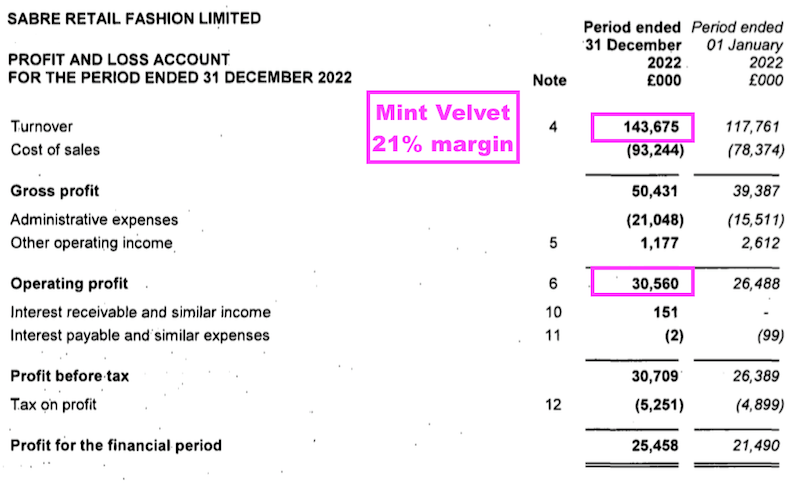

Sosandar’s margin potential with shops could be even higher than 10%. The flotation document named Mint Velvet as the group’s closest competitor:

“The Founders consider Mint Velvet to be Sosandar’s closest competitor in terms of target demographic, although Sosandar’s average price point is lower and is more trend-led, with more of a focus on dresses and workwear. Mint Velvet is more focused on casual wear.”

Mint Velvet’s last accounts showed the brand operating from 104 shops/concessions and enjoying a terrific 21% operating margin from sales of £144 million:

Despite the progress of Crew Clothing and Mint Velvet, Sosandar’s 10% margin ambition may not be easily achieved. My spreadsheet below shows the margins earned from various names on that earlier slide:

The average operating margin is 6% with some very wide variations. Quoted retail disasters such as Superdry, Quiz and Joules also provide evidence that omni-channel fashion is no guarantee of success.

Has online fashion had its day?

Sosandar’s decision to open stores may have been triggered by the increasingly unfavourable economics of selling clothes online.

Industry pioneers ASOS and Boohoo for example posted adjusted annual losses last year as they grappled with rising costs alongside fewer customers submitting fewer orders.

Both ASOS and Boohoo said reducing ‘returns’ would be vital to help lift their margins for 2024. The online fashion industry remains cursed by customers who continually send clothes back for a refund.

Sosandar’s flotation document specified returns as a “key disadvantage“, and claimed 40% of sales might be refunded throughout the online sector:

“The key disadvantages [of the online fashion market] include a downward pressure on profit margins due to a high level of returns seen in the online space (40 per cent. returns is not uncommon) and the increased logistical costs that these returns bring.“

The group’s 2019 annual report then implied the level was 50%:

“Returns levels of 50% reflect the anticipated improvement in the second half of the year from the 52% reported at interim results reflecting the different product mix in Autumn/ Winter. These levels of returns are in line with the wider industry and are in line with management’s expectations.“

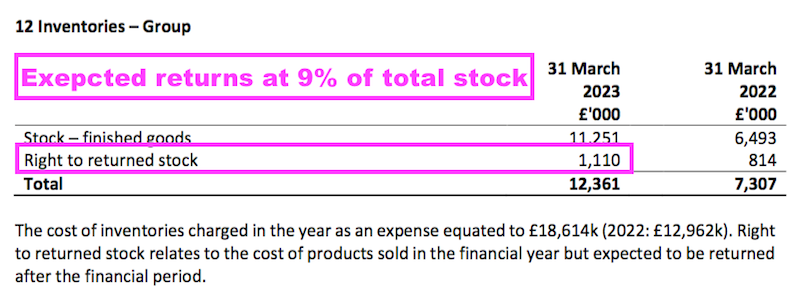

Subsequent annual reports have not disclosed a returns percentage, and Sosandar may not be faring much better than the industry. The last annual report showed 9% of stock was represented by expected returns…

…which compared to 10% for Boohoo. Operating shops may help reduce the level of returns (because customers can try on the clothes first), and the costs associated with handling the returns (because customers can return items to the store instead of using a delivery service at the retailer’s expense).

Another reason for opening shops could be the increasing popularity of online fashion ‘platforms’ operated by the likes of Next and Marks & Spencer.

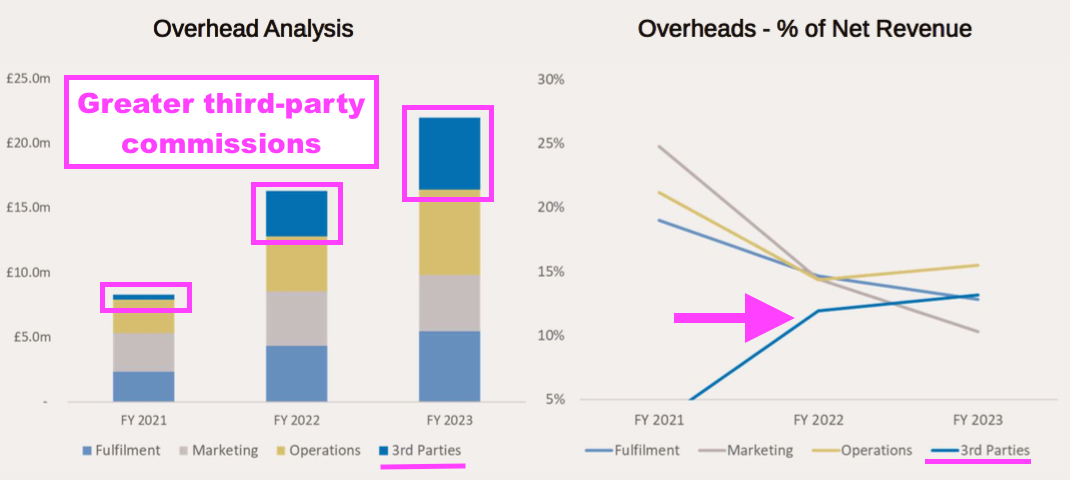

Sosandar pays commissions to such platforms for every sale, and the commissions have been increasing faster than total revenue.

For example, last month’s interims saw third-party commissions grow 41% despite sales advancing only 6%. The preceding full year witnessed commissions up 59% versus sales up 44%:

The numbers imply customers are becoming more likely to buy online through Next and Marks & Spencer rather than directly through Sosandar. If that trend continues, Sosandar could be saddled with an expensive in-house website that nobody visits.

Sosandar may well have realised Next and other platforms will eventually dominate its online sales and decided the shops are needed to ensure the group’s clothes can always be showcased independently of other brands.

The joint-CEO management

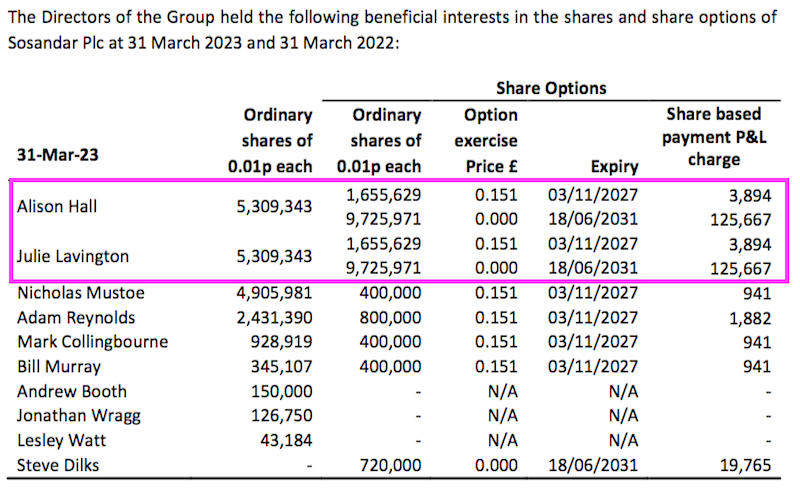

The aforementioned Alison Hall and Julie Lavington continue to lead Sosandar through an unusual joint CEO setup.

Both seem ideal candidates to steward a fast-growing fashion small-cap with a courageous goal to become “one of the largest womenswear brands globally“.

In particular, they have shown substantial entrepreneurial ambition to get the company off the ground and — perhaps unusually for bosses of a quoted retailer — actually reside within their customer demographic.

The founders are many years away from standard retirement age and I would venture are buckled into the business for the long haul.

But are the pair totally aligned with outside shareholders?

True, neither CEO has sold a share since the flotation…but neither did either CEO buy more shares during those five equity raises. In fact, director share-buying following the flotation has been disappointingly limited to a handful of non-exec purchases totalling £180,000.

Both CEOs presently own a 2%/£800,000 stake, which is not an overwhelming amount given they now collect £220,000 annual salaries:

The CEOs do like their options though. Some 27.8 million options — equating to 11% dilution — have been granted to employees, and the CEOs have 11.4 million options each:

Of the 9.7 million nil-priced options granted to the CEOs during 2021, 3.8 million vested immediately, 1.9 million were dependent on Sosandar reaching breakeven (since achieved) while 4.0 million remain dependent on the share price exceeding 60p for 60 days by 2031.

I will let you decide whether those options put management in the same boat as shareholders who participated in those five equity placings at between 15p and 32p.

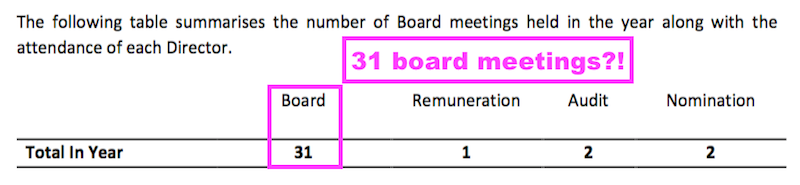

I must confess I am not sure what to make of Sosandar holding an incredible 31 general board meetings last year:

The executives appear to require non-exec input at least every two weeks, which might imply their strategy and leadership need consistent monitoring and refinement.

Recent trading and summary

A trading statement the other week reported sales during October, November and December had gained 23%. The update also confirmed market expectations for revenue to advance 10% to £46.8 million for the current year.

Profit though is expected to come in at just £100,000, which emphasised: i) how the economics of online fashion remain very difficult, and; ii) achieving a 10%-plus profit margin still has some way to go.

Of more importance than the next results will be the progress of Sosandar’s early shops, the first of which should open during the next few months with all associated funding supported by that net cash of £8 million.

Imagine 50 shops trading successfully across the UK, and Sosandar could easily achieve that £100 million-plus revenue, 10%-plus margin and £10 million-plus profit…

…to leave the recent £37 million market cap looking bonkers cheap. Crew Clothing and Mint Velvet have shown decent profits can still be achieved in the highly competitive fashion sector.

The clear risk of course is that Sosandar’s shop economics prove no better than its online economics. The worst-case scenario is the shops (and website) falter because the brand goes stale, at which point no amount of strategic rejigging will rescue shareholders.

The bull case would be more persuasive if industry ‘insiders’ were keen on the equity. As well as the founders not backing their upbeat narrative by participating in those placings, major shareholders exclude retail entrepreneurs and trade operators that could help ordinary investors form a positive judgement.

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Maynard writes about his portfolio at maynardpaton.com. He does not own shares in Sosandar.

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Maynard? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.