An iron rule in long-term investing is to understand the business. Richard adapts business school teaching to work out how companies make money.

One of the advantages private investors have over many fund managers is that we do not have to worry about being fired or losing out on bonuses just because we have not performed as well as other traders in the short-term.

The private investor’s edge

Because we are beholden only to ourselves, we are liberated from predicting how much revenue and profit a company will make for the next financial period, and free to think about how and why a business will grow over the long-term.

There are essentially three questions we must answer, which are in plain English (and business jargon):

- How a business makes money (its business model)

- Why it should make more (its strategy)

- What could stop it (risks)

Figuring this out is time-consuming, but if we focus on established businesses it is worth it. Good business models endure, and good strategies only need tweaking when the risks change or new opportunities emerge.

Find a business that knows how to make money with a coherent strategy that addresses emerging risks and opportunities, and we probably have an investment we can buy and hold. We will need to check periodically that our evaluation still rings true, but this should not be nearly as arduous as figuring it all out in the first place.

My recent work on scoring shares (Five Strikes and You’re Out), has focused on systematising the preliminary stage in the process: Finding candidates for investment by identifying businesses that already perform well judging by the numbers in SharePad.

Systematisation speeds things up, which is useful because there are thousands of potential companies to invest in and one thing private investors do not have is armies of analysts to do the research for us.

Now I am wondering whether I can systematise some of the analysis, which is working out whether these businesses are likely to continue performing well. The first element of that requires us to understand how the business makes money.

is very well suited to help us identify businesses that have performed well. When it comes to unquantifiable business models, we are going to have to be creative.

SharePad has the standard industry classifications, but as I showed in In search of high-quality sectors these can be opaque and imprecise, which makes me wonder whether we can do better.

I may have come up with a solution browsing through a book, the Business Model Navigator, in Waterstones*. The idea is to break the business model down using another set of What/How questions.

The Business Model Navigator

The Business Model Navigator is a self-help book for business people. It is written by business school professors.

The bulk of the book is a compendium of sixty business models and examples. I experienced the first of them on the summer holiday I returned from last night, courtesy of Ryainair’s “priority Boarding”. This is the “Add On” model, in which a competitively priced product or service is used to lure us into paying more for additional, higher profit margin, comforts.

While the catalogue is fascinating because of all the examples and case studies, it is quite an eclectic collection. The authors’ contention, though, is that all business models are variations on four “core dimensions”. These are:

Who? (is the customer)

Who buys the product? What kind of relationship do they expect? If the customer is commercial, who within the customer’s organisation makes the decisions?

What? (is the value proposition)

What does the company sell? What need does the product or service fulfil? What does the customer value? How does this differ from competitors?

How? (is the value proposition created)

What is the value chain (the sequence of activities that brings a product or service to market)? What are the processes, and capabilities required? What partnerships are needed?

Value? (what is the profit mechanism?)

What are the sources of income? What are the main costs? What are the main risks?

My gambit is that I can build a better impression of businesses by trying to answer the top-level Who? What? How? Value? questions when I score companies.

To do that I am making mighty generalisations and heroic assumptions. I am trying to identify the most significant customers (Who?), what they want (What?), the firm’s stand-out capabilities (How?), and the most important profit drivers (Value?).

The idea is to quickly capture the essence of the business and because I am just learning to do this, I am only attempting it for companies with scores of 0,1, and 2 according to my 5 strikes system.

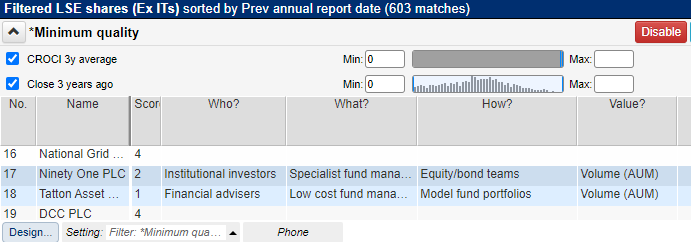

The screenshot below shows the first two business models I bottled:

Source: SharePad. Business models are defined for shares that have achieved a positive cash return on capital invested (CROCI) over the last three years and scored less than 3 according to the 5 Strikes system. The Score, and Who? What? How? and Value? columns are SharePad notes columns.

It is ironic that they are asset managers because as a self-directed investor in shares, I have little interest in asset managers (or knowledge of them).

But the objective is to learn about new investments. I am not trying to be definitive, I am just collecting impressions that I can refine into a knowledge-base over time.

Even my first stab at capturing the essence of these businesses may have yielded something valuable. Using the finest-grained industry classification, subsector, there is no way to differentiate between Ninety-One and Tatton. They are both in the Asset Managers and Custodians subsector.

But by using the core dimensions of The Business Model Navigator, we can see that they have different customers (Who?), their value proposition is different (What?) and they have different capabilities (How?) although the profit mechanism, fees levied on the value of the assets they manage for a customer, is the same.

Tatton’s aim is to bring discretionary fund management to the mass-affluent by running low-cost model fund portfolios for financial advisers.

Ninety-One was formerly part of Investec. Most of its revenue comes from institutional investors like pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and insurance companies, but it also sells through financial advisers and wealth managers. It promises long-term returns from specialist teams of portfolio managers and analysts.

I gleaned these impressions by skim-reading SharePad’s company profile, glancing through each company’s website, and by searching the annual report for obvious keywords (like “customer”). I confess, I also had a brief chat with my nephew, who works for an Independent Financial Advis!

It took longer than a minute or two, but I hope to get better at it.

~

I bought the book and read the theory. Now I have set myself the task of reading about a business model a day. Because a holiday has intervened, I have got to number 8, Crowdfunding.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Richard? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.