Bruce uses Sharepad to analyse the performance of MANU shares, listed on the NYSE. The football team presents some interesting challenges for valuing debt-funded intangible assets. Plus SDI’s profit warning, and CGEO’s Q1 results.

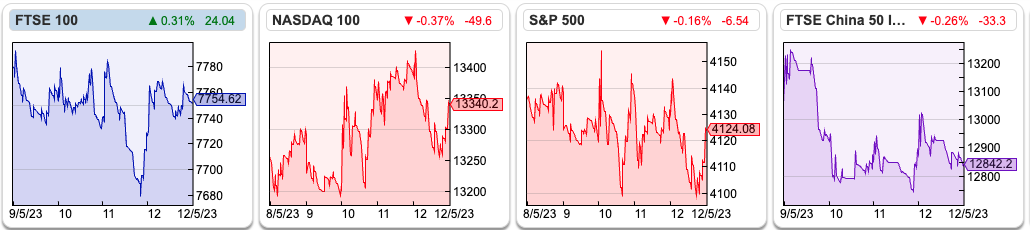

The Bank of England raised interest rates to 4.5% last week, as the FTSE 100 rose +0.7% to 7,754. Since last October sterling has risen +16% against the dollar, while the FTSE 100 is also up +13%, suggesting that we don’t need a weak pound for London-listed stocks to perform well. The Nasdaq100 rose by +0.6% while the S&P500 fell -0.3% over the last week. US inflation data suggested that the Fed may “pause” interest rate rises, however, that didn’t prevent the KBW Regional Banks (ticker KRE) falling another -5%.

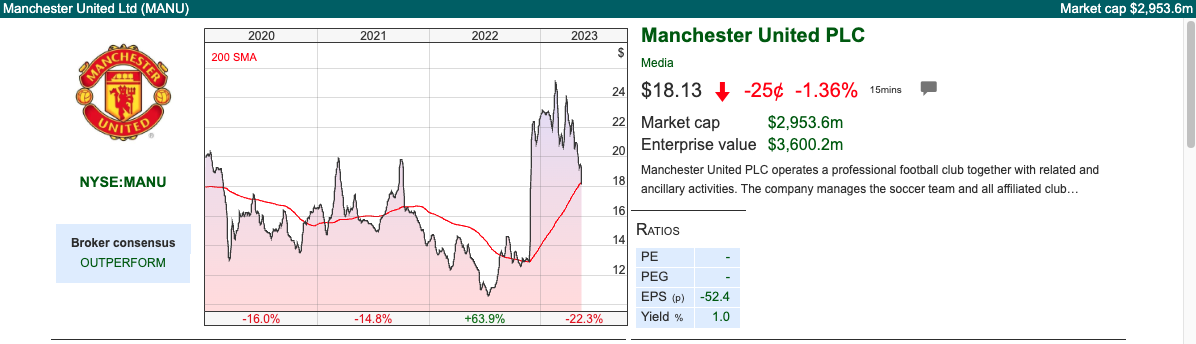

Over the weekend The Times reported that Sir Jim Ratcliffe is likely to make a successful bid for Manchester United, so I use Sharepad to look at Manchester United FC’s valuation. Although Manchester United is an English club, it currently has American ownership and is listed in New York under the ticker MANU. After that, I also look at SDI’s profit warning and CGEO’s Q1 results.

The Manchester United analysis doesn’t look at performance on the pitch. Instead, it draws out valuation-related themes, using Sharepad, to look at EBITDA v Free Cash Flow, the debt-funded intangible assets and dual-class share structures. In both professional sport and investing in a modern economy, success increasingly comes from things that we can’t touch (teamwork, culture, mindset, training). To explore this theme further, I recommend two books: Capitalism Without Capital and The Goldmine Effect.

Although MANU is a listed corporation, I have some sympathy for the fans, who believe they are stakeholders in an institution, rather than customers whose value is to be monetised.

I also agree with fans who dislike wealthy individuals associating themselves with their football clubs, simply to legitimise wealth. Though it is normally good advice to separate emotions from investing, it is understandable that fans prefer an owner to have made an emotional connection (ie local boyhood fan) to a club, rather than just a financial one. In 2022 the Glazer family were voted the worst owners in the Premier League. Brentford FC owner Matthew Benham, who has the least financial resources of any Premier League club owner, received the highest approval rating from fans.

One heretical idea I have is that modern capitalism took the wrong path when (previously stakeholder-owned institutions) like the stock exchange and building societies – particularly Northern Rock and Halifax – began viewing themselves as value-maximising financial corporations. In the late 1990’s football clubs went down that route too. There would be an outcry if an Oxbridge college, the National Gallery or even the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club (Wimbledon) sold itself to an oil-rich SWF or listed on an overseas stock exchange. Why should football clubs be different from our other middle-class institutions?

Manchester Utd FC

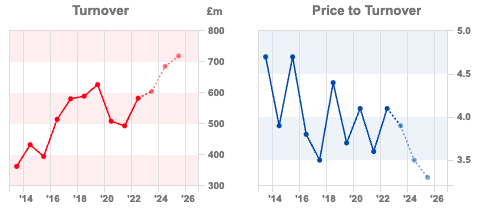

The company has a June year-end, and most recently reported Q2 to Dec 2023, when management reiterated FY Jun 2023 revenues of £590m to £610m and its adjusted EBITDA guidance of £125m to £140m. That implies mid-single-digit revenue growth, as the team failed to qualify for the Champions League in 2022-3.

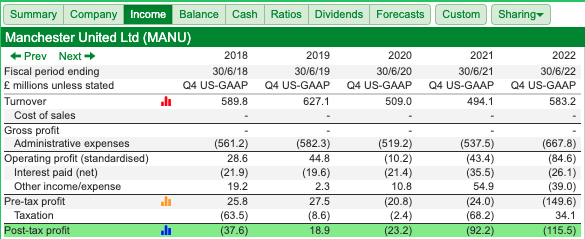

Income statement: A brief look at Sharepad’s “Income” tab, shows that MANU have been loss-making for 4 of the last 5 years. In FY June 2019, the year that they did make a profit it was less than £20m after tax. Some, but not all, of those loss-making years are due to the pandemic.

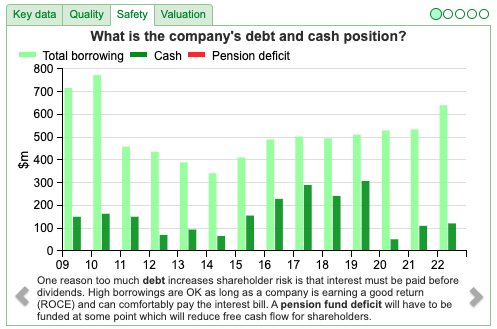

Balance sheet: As of Dec 2022 the company had £871bn of intangible assets (mainly players), funded with £535m of long-term debt, just under half of which will need to be refinanced by 2027. Usually, it is difficult to persuade debt markets to fund investment in intangible assets, because their value is more uncertain than physical property (land, buildings etc). Football players do have a value in the transfer market, however, they can lose form and suffer from injuries. The club’s borrowing is denominated in US dollars ($650m), and has recently increased over the pandemic, but is down from a peak of almost $800m a decade ago. It represents around 4x adj EBITDA. Debt amplifies returns if things go well, but creates additional risks if results on the pitch disappoint. For instance, if the team fails to qualify for the Champions League two years in a row (see below).

EBITDA: Readers will know I am not a fan of adj EBITDA. Unlike an industrial company, Man Utd can include staff costs (players) on their balance sheet, and then amortise over the length of their contracts. Hence the amortisation charge of £45m was 12.5x higher than depreciation. There was also £28m capital expenditure on intangible assets (ie buying players in the transfer market).

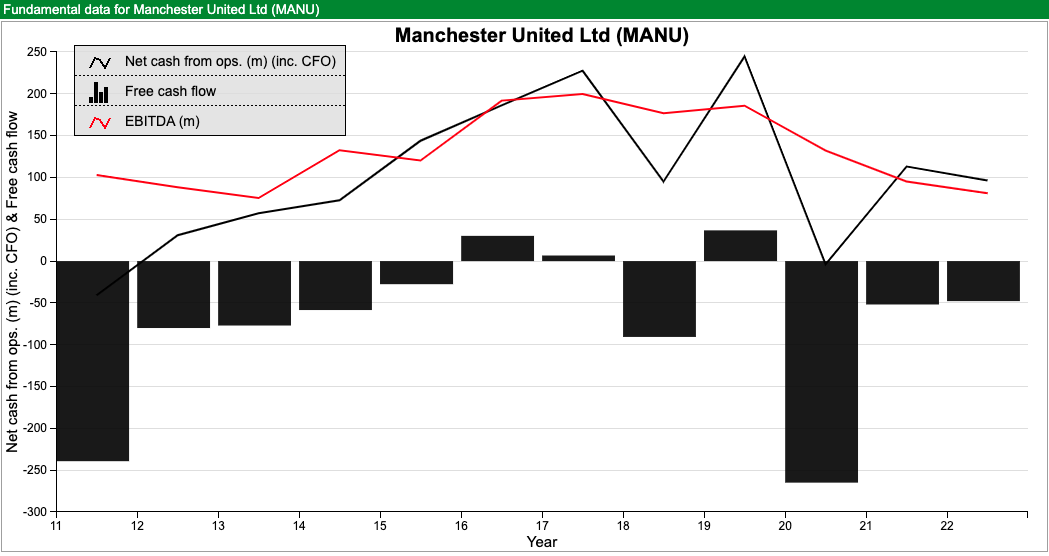

Cashflow: This means that though adj EBITDA (red line) and net cash from operations (black line) looks very healthy (except for the pandemic year), Free Cash Flow (black blocks) which deducts the capital costs (players), seems a better measure to focus on, as investing in players is likely to be a continued cost of doing business.

Company management often encourage investors to ignore depreciation and amortisation by emphasising EBITDA. I find Sharepad’s tabs, which allow users to toggle between the p&l and cashflow, incredibly useful for providing a better view on the underlying shape of the business than EBITDA. For a normal company, staff costs are expensed through the p&l and have to be recognised in the year that they are incurred. Effectively football clubs have the same accounting treatment as computer games companies (DEVO, FDEV, TBLD and TM17) that are allowed to spread their programmers’ wages over the life of the games that they have developed.

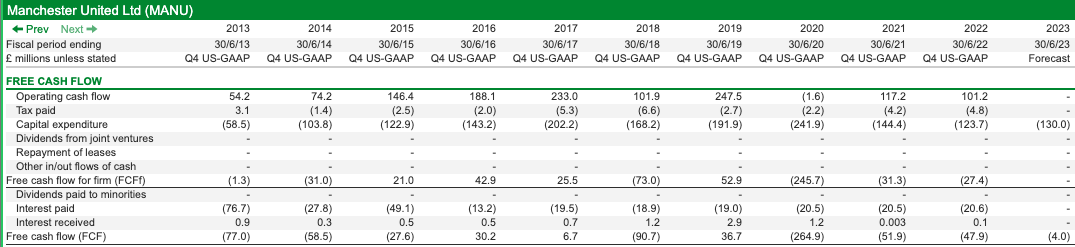

Below is a Sharepad table showing a reconciliation of operating cashflow to FCF. It shows two definitions of FCF and FCFf, the latter is Free Cash Flow to the firm. This doesn’t include the interest paid on the £550-£750m of debt, which has been controversial with supporters. In total this interest cost has been almost £300m over the last 10 years:

To prevent wealthy owners buying success, the football authorities have introduced controls on squad costs (mainly players but also coaches, transfers and agent fees are included). Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations mean that relevant costs can’t exceed revenues on a cumulative basis over a three-year period. Significant delays in settling creditor liabilities are also punished, as well as if debt exceeds 7x relevant earnings, which presumably is to prevent wealthy shareholders providing financial support on non-commercial terms. FFP means squad costs will fall further from 90% of revenue in 2023/24, down to 70% from 2025/26 onwards. These FFP rules apply to all teams, and in theory, ought to benefit shareholders. Football, like investment banking, tends to be a business where the benefits of increasing revenue accrue to the “star players” rather than shareholders.

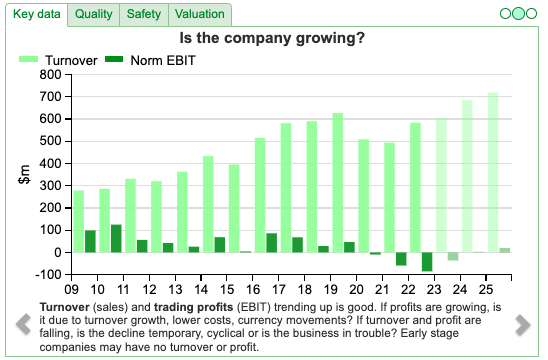

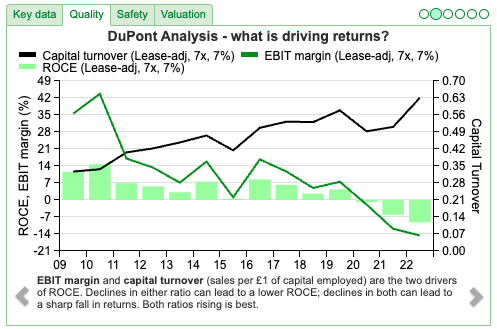

The financial track record is unconvincing, as this Sharepad chart shows, the EBIT margin peaked at 17% in FY Jun 2016 and FY Jun 2011, growing revenues haven’t translated into growing profits.

A and B Shares: There are two share classes, the six descendants of Malcolm Glazer own all of the B shares which are entitled to 10 votes per share. The A shares, which are listed in New York and are owned by the likes of Lindsell Train, carry one vote per share. Effectively the Glazer family control over 95% of the voting rights. Dual-class voting structures are not that unusual, Mark Zuckerberg retains control of Facebook (NYSE:META) this way, Jack Dorsey Block (NYSE:SQ) and in London we have WISE and Sir Martin Sorrell’s SFOR. A dual-class share structure is usually justified as a method of protecting visionary founders, with a track record of non-conformist ideas that turn out to be wildly successful, from being outvoted by less imaginative ordinary shareholders. It’s hard to see why this justification should apply to the Glazer family though.

Profitability: Although the club’s brand may resonate around the world, Sharepad’s quality measures show that this isn’t reflected in the financial results. Clearly, the pandemic has been difficult for football teams, but even so, negative RoCE, CRoCI and EBIT margins are not supporting the high valuation.

Champions League: Currently there is significant uncertainty about whether the team qualifies for next season’s Champions League (they need to finish in the top 4 of the Premier League). Inclusive of prize money and broadcasting and matchday revenue, the club earned £75m from the Champions League in 2021/22, the last year that they qualified. The 20F warns that failure to qualify for European competitions is not just a direct financial negative, but also affects the club’s ability to attract and retain players, supporters and sponsors. For instance, Adidas would reduce payments by 30% if MANU fail to qualify for the Champions League for two consecutive seasons. That feels rather uncomfortable, given the club’s debt burden.

Valuation: MANU’s current market cap implies 3.5x Jun 2024F revenues, which seems expensive for an intangible heavy, indebted, people business lacking free cash flow. For comparison, Burford the litigation finance company, which also has some of those characteristics is on 4x 2023F forecast revenue.

The proposed $6-7bn valuation of MANU, that the Glazer family seem to believe the club is worth, implies around 10x revenues. That compares to 5x revenues for Chelsea (£2.5bn Todd Boehly, Clearlake), 4.5x revenues for AC Milan (US Private Equity firm RedBird) and less than 2x revenues for Newcastle Utd (Saudi Arabia PIF). The latter will likely finish above Man Utd in the Premier League this season and was sold for £305m in October 2021. The FT valued MANU using a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) at $1.6bn. Another startling valuation statistic is that three decades ago, Michael Knighton tried to buy Manchester United for £20m, the offer was accepted by the Board but fell through because Knighton’s financial backers dropped out.

Opinion: The bull case is that football could become a ‘winner takes all’ type industry, with a few super clubs like Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, Paris St Germain, Inter and AC Milan, Manchester City and Brentford FC. It can be an excellent investment strategy to pick a winning brand in an industry that is globalising. Nike Inc (market cap $200bn, RoCE 23%, EBIT margin 14%), LVMH (market cap €444bn, RoCE 19%, EBIT margin 27%) and chip maker ARM that is soon to be listed in New York, strike me as good examples.

To me though, football clubs trade more like trophy assets such as yachts, race horses, Picasso’s and supercars. Wealthy people own expensive assets not to earn an economic return, but because they legitimise success. The irony is, that while we might think of Man Utd as a ‘trophy asset’, the most recent prize that the club has won is the Caraboa Cup.

Georgia Capital Q1 March Trading Update

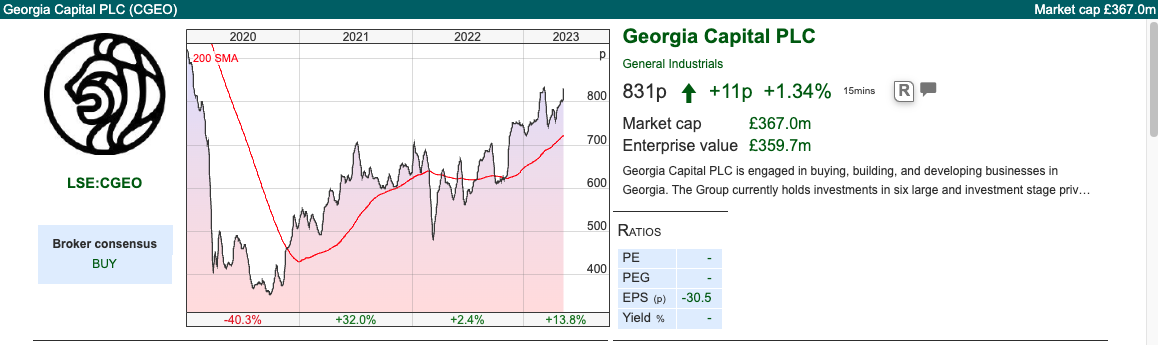

I last wrote about this Bank of Georgia spin-off at the beginning of last year, when they announced the disposal of 80% of their water utility business for $180m. Since then Putin has invaded Ukraine, but the shares after an initial sell-off have held up well. CGEO continue to sell non-core assets, with further sales of two hotels and a vacant land plot in Tbilisi for a total consideration of US$ 28m. In April, after the quarter end, they sold an under-construction hotel in Tbilisi for $8.4m.

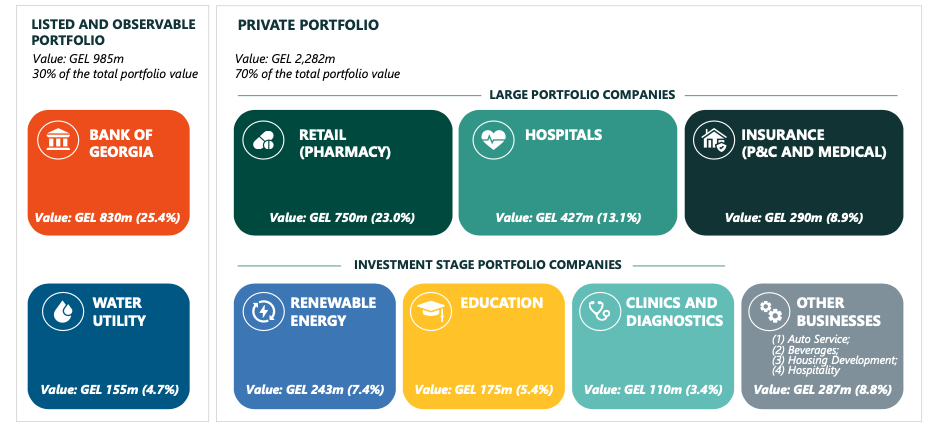

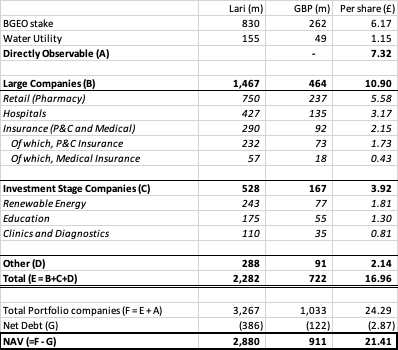

The NAV per share was £21.41 at the end of March, up +6% over the quarter, half of that increase was driven by the appreciation of the Georgian Lari versus sterling. Just under a third of the NAV is directly observable mark-to-market holdings in BGEO (worth 617p per share) and the Water Utility business that they retained a 20% minority stake in (worth 115p per share). Adjusting for those two items means the remaining 70% of CGEO NAV (the private portfolio in the graphic below) has an implied value of just 68p. That is a network of pharmacies, a couple of hospitals, an insurance business plus smaller renewable energy, education etc is trading at a 95% discount to NAV.

I have created a simplified table, which shows the portfolio of Large Companies (B) NAV equates to 1090p per share, Investment Stage (C) 392p per share, and Other (D) 214p per share, less net debt (G) of 287p per share.

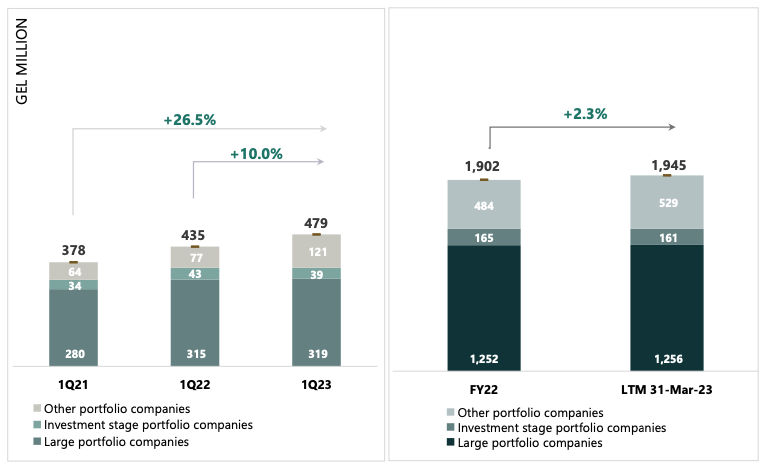

Operating performance: There are a lot of moving parts as effectively CGEO is a conglomerate. Aggregate revenue was up +10% to GEL479m (or £151m) in Q1. Last 12 Month’s revenue of GEL1,945m equates to £614m. I am pleased that the company has improved disclosure of results in their divisions, publishing a p&l down to attributable profit, cashflow and balance sheet. Previously they only showed divisional EBITDA, which I was critical of.

Around 40% of revenues come from the 368 pharmacies, with a third market share in Georgia, plus some smaller operations in Armenia and Azerbaijan. They saw flat revenues, as the strong Lari meant a significant decrease in pharmaceutical prices and there was also a negative effect of the Georgian Government’s External Reference Pricing model, which introduced a maximum retail price on prescription medicines. Longer term they are targeting double-digit revenue growth and an EBITDA margin of 9% which seems realistic to me. Pharmacies tend to be a recession-proof business, as health services need to distribute prescription drugs and can be attractive to Private Equity for that reason (for example KKR’s £11bn bid for Boots in 2007).

Hospitals (15% of revenue) and Renewable Energy (10% of revenue) should both be growth areas, however, one hospital (Iashvili Paediatric) was temporarily closed for renovations and they sold another hospital (Traumatology) in April last year. Renewables also saw revenue fall -17% due to maintenance work on one of the hydro dams (Mestiachala). Insurance (9% of revenue) was up around +20%.

Valuation: As of the 5th May the CGEO NAV had risen to 2259p, implying an -60% discount. There’s a fun NAV calculator on the company’s website, where you can enter your own valuation assumptions. To be fair, there are some similarly large conglomerate discounts elsewhere in the market at the moment: Harbourvest Private Equity (-47% discount to NAV), IP Group (-60% discount to NAV) and Oceans Wilson, which also published a Q1 trading update last week (-48% discount to NAV). I wrote about OCN last summer, and since then revenues in the Ports business (Wilson Sons) are up +8% in dollars Q1 v Q1 2022, though EBITDA was flat. The discount to NAV hasn’t changed much.

Investors: The largest shareholder in CGEO is Gemsstock, a macro hedge fund set up by Al Breach, an ex-UBS equity research analyst, who I met when he was on the board of Bank of Georgia. Gemsstock own 11% of the shares, and Allan Gray, a South African investment vehicle is the next largest shareholder 6.6%. More recognisable names such as Lazard, Schroders, BlackRock and GLG own less than 5%.

Opinion: There’s clearly some political risk investing in Georgia, which may express itself through a weak currency at some point. I own the shares as I think the investment case makes sense as part of a diversified portfolio. There’s plenty of growth potential, and the business should become easier to understand as management sell the parts that are non-core.

SDI FY Apr Trading Update/Profit Warning

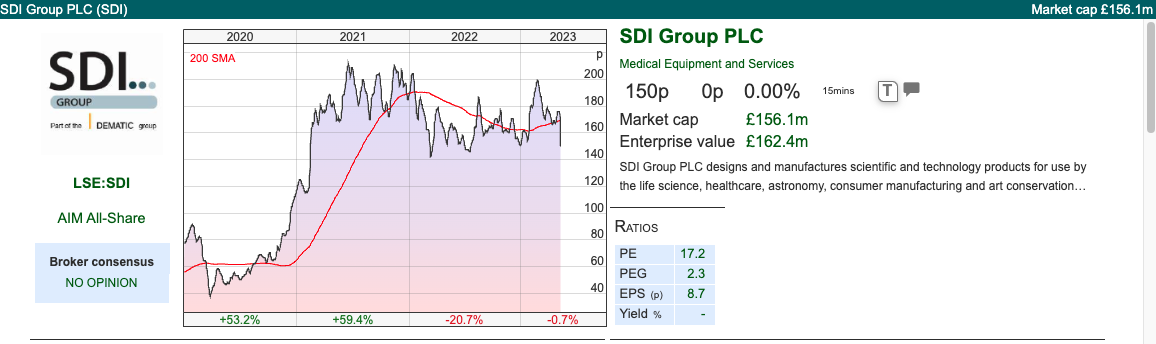

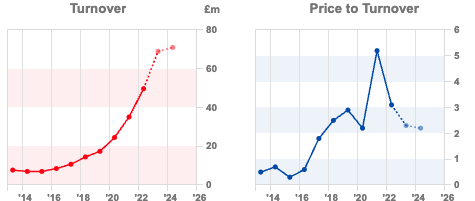

This scientific instruments and lenses company announced an “in line” trading update for this year to April. That implies FY Apr 2023F revenue of £66m (+33%) and Adj PBT of £11.8m (+59%). That’s an impressive level of growth, helped by £8.5m from their Atik Cameras division, which supplies components for PCR testing machines for Covid. The company has said at their H1 results in December that they had no visibility on orders for future years.

Forecasts: Last week’s RNS says that it is “in line with current market expectations” which is true for this year. However, the company warns that they no longer expect more PCR-related contracts from their customer, so have removed the related for FY Apr 2024F. They don’t quantify this in their RNS but FinnCap, their broker, reduced FY Apr 2024F PBT and EPS by 17%, and 21% to £9.8m and 7.3p. FinnCap have not published a FY Apr 2025F forecast, perhaps suggesting that SDI management are nervous about future visibility.

Valuation: Following the forecast reduction the shares are trading on 21x PER Apr 2024F, or 2.2 revenue the same year. One area of concern is at the H1 stage almost all of the group’s +25% revenue growth had been driven by acquisitions. Even with the Atik Camera’s division benefiting from their large PCR camera order, group organic revenue growth was less than +4% in H1 to October. The high rating is hard to justify if organic growth is below inflation.

Opinion: There seems to be a contradiction in the messaging. Management warned at the H1 stage, that they had no visibility on future PCR contracts, yet this still seems to have resulted in reduced expectations for the FY Apr 2024F. Martin Flitton has written up his talk with management here, but I am not sure he has managed to square that circle either.

I own SDI, and feel management deserve the benefit of the doubt given their track record. The shares have already de-rated from above 5x sales a couple of years ago.

Notes

The author owns shares in CGEO, SDI

Bruce Packard

brucepackard.com

Got some thoughts on this week’s commentary from Bruce? Share these in the SharePad “Weekly Market Commentary” chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for “Weekly Market Commentary” chat.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Weekly Market Commentary | 16/05/23 | MANU, SDI, CGEO | Valuing a Trophy Asset

Bruce uses Sharepad to analyse the performance of MANU shares, listed on the NYSE. The football team presents some interesting challenges for valuing debt-funded intangible assets. Plus SDI’s profit warning, and CGEO’s Q1 results.

The Bank of England raised interest rates to 4.5% last week, as the FTSE 100 rose +0.7% to 7,754. Since last October sterling has risen +16% against the dollar, while the FTSE 100 is also up +13%, suggesting that we don’t need a weak pound for London-listed stocks to perform well. The Nasdaq100 rose by +0.6% while the S&P500 fell -0.3% over the last week. US inflation data suggested that the Fed may “pause” interest rate rises, however, that didn’t prevent the KBW Regional Banks (ticker KRE) falling another -5%.

Over the weekend The Times reported that Sir Jim Ratcliffe is likely to make a successful bid for Manchester United, so I use Sharepad to look at Manchester United FC’s valuation. Although Manchester United is an English club, it currently has American ownership and is listed in New York under the ticker MANU. After that, I also look at SDI’s profit warning and CGEO’s Q1 results.

The Manchester United analysis doesn’t look at performance on the pitch. Instead, it draws out valuation-related themes, using Sharepad, to look at EBITDA v Free Cash Flow, the debt-funded intangible assets and dual-class share structures. In both professional sport and investing in a modern economy, success increasingly comes from things that we can’t touch (teamwork, culture, mindset, training). To explore this theme further, I recommend two books: Capitalism Without Capital and The Goldmine Effect.

Although MANU is a listed corporation, I have some sympathy for the fans, who believe they are stakeholders in an institution, rather than customers whose value is to be monetised.

I also agree with fans who dislike wealthy individuals associating themselves with their football clubs, simply to legitimise wealth. Though it is normally good advice to separate emotions from investing, it is understandable that fans prefer an owner to have made an emotional connection (ie local boyhood fan) to a club, rather than just a financial one. In 2022 the Glazer family were voted the worst owners in the Premier League. Brentford FC owner Matthew Benham, who has the least financial resources of any Premier League club owner, received the highest approval rating from fans.

One heretical idea I have is that modern capitalism took the wrong path when (previously stakeholder-owned institutions) like the stock exchange and building societies – particularly Northern Rock and Halifax – began viewing themselves as value-maximising financial corporations. In the late 1990’s football clubs went down that route too. There would be an outcry if an Oxbridge college, the National Gallery or even the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club (Wimbledon) sold itself to an oil-rich SWF or listed on an overseas stock exchange. Why should football clubs be different from our other middle-class institutions?

Manchester Utd FC

The company has a June year-end, and most recently reported Q2 to Dec 2023, when management reiterated FY Jun 2023 revenues of £590m to £610m and its adjusted EBITDA guidance of £125m to £140m. That implies mid-single-digit revenue growth, as the team failed to qualify for the Champions League in 2022-3.

Income statement: A brief look at Sharepad’s “Income” tab, shows that MANU have been loss-making for 4 of the last 5 years. In FY June 2019, the year that they did make a profit it was less than £20m after tax. Some, but not all, of those loss-making years are due to the pandemic.

Balance sheet: As of Dec 2022 the company had £871bn of intangible assets (mainly players), funded with £535m of long-term debt, just under half of which will need to be refinanced by 2027. Usually, it is difficult to persuade debt markets to fund investment in intangible assets, because their value is more uncertain than physical property (land, buildings etc). Football players do have a value in the transfer market, however, they can lose form and suffer from injuries. The club’s borrowing is denominated in US dollars ($650m), and has recently increased over the pandemic, but is down from a peak of almost $800m a decade ago. It represents around 4x adj EBITDA. Debt amplifies returns if things go well, but creates additional risks if results on the pitch disappoint. For instance, if the team fails to qualify for the Champions League two years in a row (see below).

EBITDA: Readers will know I am not a fan of adj EBITDA. Unlike an industrial company, Man Utd can include staff costs (players) on their balance sheet, and then amortise over the length of their contracts. Hence the amortisation charge of £45m was 12.5x higher than depreciation. There was also £28m capital expenditure on intangible assets (ie buying players in the transfer market).

Cashflow: This means that though adj EBITDA (red line) and net cash from operations (black line) looks very healthy (except for the pandemic year), Free Cash Flow (black blocks) which deducts the capital costs (players), seems a better measure to focus on, as investing in players is likely to be a continued cost of doing business.

Company management often encourage investors to ignore depreciation and amortisation by emphasising EBITDA. I find Sharepad’s tabs, which allow users to toggle between the p&l and cashflow, incredibly useful for providing a better view on the underlying shape of the business than EBITDA. For a normal company, staff costs are expensed through the p&l and have to be recognised in the year that they are incurred. Effectively football clubs have the same accounting treatment as computer games companies (DEVO, FDEV, TBLD and TM17) that are allowed to spread their programmers’ wages over the life of the games that they have developed.

Below is a Sharepad table showing a reconciliation of operating cashflow to FCF. It shows two definitions of FCF and FCFf, the latter is Free Cash Flow to the firm. This doesn’t include the interest paid on the £550-£750m of debt, which has been controversial with supporters. In total this interest cost has been almost £300m over the last 10 years:

To prevent wealthy owners buying success, the football authorities have introduced controls on squad costs (mainly players but also coaches, transfers and agent fees are included). Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations mean that relevant costs can’t exceed revenues on a cumulative basis over a three-year period. Significant delays in settling creditor liabilities are also punished, as well as if debt exceeds 7x relevant earnings, which presumably is to prevent wealthy shareholders providing financial support on non-commercial terms. FFP means squad costs will fall further from 90% of revenue in 2023/24, down to 70% from 2025/26 onwards. These FFP rules apply to all teams, and in theory, ought to benefit shareholders. Football, like investment banking, tends to be a business where the benefits of increasing revenue accrue to the “star players” rather than shareholders.

The financial track record is unconvincing, as this Sharepad chart shows, the EBIT margin peaked at 17% in FY Jun 2016 and FY Jun 2011, growing revenues haven’t translated into growing profits.

A and B Shares: There are two share classes, the six descendants of Malcolm Glazer own all of the B shares which are entitled to 10 votes per share. The A shares, which are listed in New York and are owned by the likes of Lindsell Train, carry one vote per share. Effectively the Glazer family control over 95% of the voting rights. Dual-class voting structures are not that unusual, Mark Zuckerberg retains control of Facebook (NYSE:META) this way, Jack Dorsey Block (NYSE:SQ) and in London we have WISE and Sir Martin Sorrell’s SFOR. A dual-class share structure is usually justified as a method of protecting visionary founders, with a track record of non-conformist ideas that turn out to be wildly successful, from being outvoted by less imaginative ordinary shareholders. It’s hard to see why this justification should apply to the Glazer family though.

Profitability: Although the club’s brand may resonate around the world, Sharepad’s quality measures show that this isn’t reflected in the financial results. Clearly, the pandemic has been difficult for football teams, but even so, negative RoCE, CRoCI and EBIT margins are not supporting the high valuation.

Champions League: Currently there is significant uncertainty about whether the team qualifies for next season’s Champions League (they need to finish in the top 4 of the Premier League). Inclusive of prize money and broadcasting and matchday revenue, the club earned £75m from the Champions League in 2021/22, the last year that they qualified. The 20F warns that failure to qualify for European competitions is not just a direct financial negative, but also affects the club’s ability to attract and retain players, supporters and sponsors. For instance, Adidas would reduce payments by 30% if MANU fail to qualify for the Champions League for two consecutive seasons. That feels rather uncomfortable, given the club’s debt burden.

Valuation: MANU’s current market cap implies 3.5x Jun 2024F revenues, which seems expensive for an intangible heavy, indebted, people business lacking free cash flow. For comparison, Burford the litigation finance company, which also has some of those characteristics is on 4x 2023F forecast revenue.

The proposed $6-7bn valuation of MANU, that the Glazer family seem to believe the club is worth, implies around 10x revenues. That compares to 5x revenues for Chelsea (£2.5bn Todd Boehly, Clearlake), 4.5x revenues for AC Milan (US Private Equity firm RedBird) and less than 2x revenues for Newcastle Utd (Saudi Arabia PIF). The latter will likely finish above Man Utd in the Premier League this season and was sold for £305m in October 2021. The FT valued MANU using a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) at $1.6bn. Another startling valuation statistic is that three decades ago, Michael Knighton tried to buy Manchester United for £20m, the offer was accepted by the Board but fell through because Knighton’s financial backers dropped out.

Opinion: The bull case is that football could become a ‘winner takes all’ type industry, with a few super clubs like Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, Paris St Germain, Inter and AC Milan, Manchester City and Brentford FC. It can be an excellent investment strategy to pick a winning brand in an industry that is globalising. Nike Inc (market cap $200bn, RoCE 23%, EBIT margin 14%), LVMH (market cap €444bn, RoCE 19%, EBIT margin 27%) and chip maker ARM that is soon to be listed in New York, strike me as good examples.

To me though, football clubs trade more like trophy assets such as yachts, race horses, Picasso’s and supercars. Wealthy people own expensive assets not to earn an economic return, but because they legitimise success. The irony is, that while we might think of Man Utd as a ‘trophy asset’, the most recent prize that the club has won is the Caraboa Cup.

Georgia Capital Q1 March Trading Update

I last wrote about this Bank of Georgia spin-off at the beginning of last year, when they announced the disposal of 80% of their water utility business for $180m. Since then Putin has invaded Ukraine, but the shares after an initial sell-off have held up well. CGEO continue to sell non-core assets, with further sales of two hotels and a vacant land plot in Tbilisi for a total consideration of US$ 28m. In April, after the quarter end, they sold an under-construction hotel in Tbilisi for $8.4m.

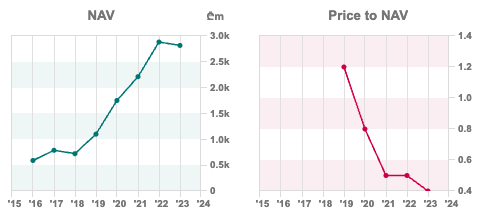

The NAV per share was £21.41 at the end of March, up +6% over the quarter, half of that increase was driven by the appreciation of the Georgian Lari versus sterling. Just under a third of the NAV is directly observable mark-to-market holdings in BGEO (worth 617p per share) and the Water Utility business that they retained a 20% minority stake in (worth 115p per share). Adjusting for those two items means the remaining 70% of CGEO NAV (the private portfolio in the graphic below) has an implied value of just 68p. That is a network of pharmacies, a couple of hospitals, an insurance business plus smaller renewable energy, education etc is trading at a 95% discount to NAV.

I have created a simplified table, which shows the portfolio of Large Companies (B) NAV equates to 1090p per share, Investment Stage (C) 392p per share, and Other (D) 214p per share, less net debt (G) of 287p per share.

Operating performance: There are a lot of moving parts as effectively CGEO is a conglomerate. Aggregate revenue was up +10% to GEL479m (or £151m) in Q1. Last 12 Month’s revenue of GEL1,945m equates to £614m. I am pleased that the company has improved disclosure of results in their divisions, publishing a p&l down to attributable profit, cashflow and balance sheet. Previously they only showed divisional EBITDA, which I was critical of.

Around 40% of revenues come from the 368 pharmacies, with a third market share in Georgia, plus some smaller operations in Armenia and Azerbaijan. They saw flat revenues, as the strong Lari meant a significant decrease in pharmaceutical prices and there was also a negative effect of the Georgian Government’s External Reference Pricing model, which introduced a maximum retail price on prescription medicines. Longer term they are targeting double-digit revenue growth and an EBITDA margin of 9% which seems realistic to me. Pharmacies tend to be a recession-proof business, as health services need to distribute prescription drugs and can be attractive to Private Equity for that reason (for example KKR’s £11bn bid for Boots in 2007).

Hospitals (15% of revenue) and Renewable Energy (10% of revenue) should both be growth areas, however, one hospital (Iashvili Paediatric) was temporarily closed for renovations and they sold another hospital (Traumatology) in April last year. Renewables also saw revenue fall -17% due to maintenance work on one of the hydro dams (Mestiachala). Insurance (9% of revenue) was up around +20%.

Valuation: As of the 5th May the CGEO NAV had risen to 2259p, implying an -60% discount. There’s a fun NAV calculator on the company’s website, where you can enter your own valuation assumptions. To be fair, there are some similarly large conglomerate discounts elsewhere in the market at the moment: Harbourvest Private Equity (-47% discount to NAV), IP Group (-60% discount to NAV) and Oceans Wilson, which also published a Q1 trading update last week (-48% discount to NAV). I wrote about OCN last summer, and since then revenues in the Ports business (Wilson Sons) are up +8% in dollars Q1 v Q1 2022, though EBITDA was flat. The discount to NAV hasn’t changed much.

Investors: The largest shareholder in CGEO is Gemsstock, a macro hedge fund set up by Al Breach, an ex-UBS equity research analyst, who I met when he was on the board of Bank of Georgia. Gemsstock own 11% of the shares, and Allan Gray, a South African investment vehicle is the next largest shareholder 6.6%. More recognisable names such as Lazard, Schroders, BlackRock and GLG own less than 5%.

Opinion: There’s clearly some political risk investing in Georgia, which may express itself through a weak currency at some point. I own the shares as I think the investment case makes sense as part of a diversified portfolio. There’s plenty of growth potential, and the business should become easier to understand as management sell the parts that are non-core.

SDI FY Apr Trading Update/Profit Warning

This scientific instruments and lenses company announced an “in line” trading update for this year to April. That implies FY Apr 2023F revenue of £66m (+33%) and Adj PBT of £11.8m (+59%). That’s an impressive level of growth, helped by £8.5m from their Atik Cameras division, which supplies components for PCR testing machines for Covid. The company has said at their H1 results in December that they had no visibility on orders for future years.

Forecasts: Last week’s RNS says that it is “in line with current market expectations” which is true for this year. However, the company warns that they no longer expect more PCR-related contracts from their customer, so have removed the related for FY Apr 2024F. They don’t quantify this in their RNS but FinnCap, their broker, reduced FY Apr 2024F PBT and EPS by 17%, and 21% to £9.8m and 7.3p. FinnCap have not published a FY Apr 2025F forecast, perhaps suggesting that SDI management are nervous about future visibility.

Valuation: Following the forecast reduction the shares are trading on 21x PER Apr 2024F, or 2.2 revenue the same year. One area of concern is at the H1 stage almost all of the group’s +25% revenue growth had been driven by acquisitions. Even with the Atik Camera’s division benefiting from their large PCR camera order, group organic revenue growth was less than +4% in H1 to October. The high rating is hard to justify if organic growth is below inflation.

Opinion: There seems to be a contradiction in the messaging. Management warned at the H1 stage, that they had no visibility on future PCR contracts, yet this still seems to have resulted in reduced expectations for the FY Apr 2024F. Martin Flitton has written up his talk with management here, but I am not sure he has managed to square that circle either.

I own SDI, and feel management deserve the benefit of the doubt given their track record. The shares have already de-rated from above 5x sales a couple of years ago.

Notes

The author owns shares in CGEO, SDI

Bruce Packard

brucepackard.com

Got some thoughts on this week’s commentary from Bruce? Share these in the SharePad “Weekly Market Commentary” chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for “Weekly Market Commentary” chat.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.