The fabric and wallpaper business is cheap and has a profitable past. Richard considers whether recovery will lead to sustainable growth…

I am looking into Sanderson Design because an investor I know rates it and because as a former investor in Colefax, a customer and a competitor of Sanderson, I know (a little) about the fabric and wallpaper business.

Also, Sanderson published its annual report in June.

Do your own research

Readers of my article on MacFarlane will know I have mixed feelings about researching stocks other investors I respect have already ‘discovered’.

While it is comforting that others own shares in a company we are considering, respectable investors can be wrong or have different objectives.

That is as true of me as it is of anyone else. The basic point is to trust, but verify.

There are hurdles to overcome before I consider Sanderson Design as an investment:

- Profitability declined over the second half of the last decade. The company has changed its name from Walker Greenbank, has new management, and is something of a turnaround. To my mind, turnarounds are inherently riskier than companies executing already successful strategies.

- Eight years of seeing the industry through the eyes of Colefax taught me that fabric and wallpaper is a difficult business to scale profitably. Launching new designs is expensive and not always successful. Many small family owned-competitors earn sufficient profits to stay in business, but they are not keen to sell up cheaply. A company like Colefax does not want its exclusive designs on sale in B&Q because they will lose their cachet and wealthy customers employing interior designers will not buy them.

Rather than grow by acquisition, or find new routes to market, Colefax chooses to improve returns to shareholders by buying back shares. This strategy is prudent and unexciting, but perhaps it is the best one. Colefax has been a good investment.

Despite a rockier share price trajectory, Sanderson has not done badly over the long-term either, but it has induced a lot more anxiety in shareholders:

Colefax shares have appreciated 219% since I first got involved (b’s indicate buys in the model Share Sleuth portfolio I run for Interactive Investor, an investment platform, and s’s indicate sells. I sold out completely in 2019). Sanderson’s share price has been more volatile, but it has ended up in a similar place.

Sanderson and Colefax share many similarities. They both sell up-market fabric and wallpaper, principally in the US, the UK and Europe. Both have heritage brands and more contemporary styles.

Sanderson owns the eponymous Sanderson brand, which dates back to the 19th century, and Morris & Co, which owns the archive of the 19th-century textile designer William Morris.

But Colefax and Sanderson are not doppelgangers.

Sanderson is a manufacturer, as well as a designer, one of its customers, is Colefax. Colefax is a decorator as well as a designer.

These elements of vertical integration are interesting because it means the businesses are differentiated by more than just the designs they produce, and they have capabilities that might make them better designers.

Being a manufacturer gives Sanderson control of costs and insight into what is possible when pushing the boundaries of design.

By decorating, Colefax gains insight from its customers.

Curiously, judging by the stats in SharePad, the difference between the volatility of the two company’s share prices may not be explained by differences in their performance.

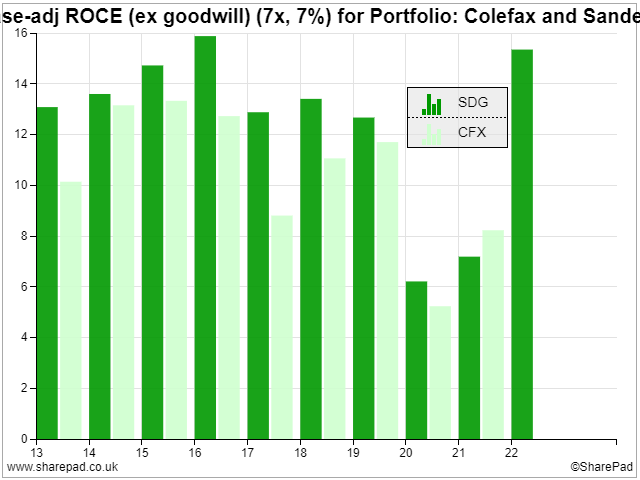

In terms of Return on Capital Employed (ROCE), there is not much to choose between them over the last decade, if anything Sanderson is the more profitable:

ROCE Comparison. Colefax has yet to publish its results for the year 2022, a strong recovery is anticipated by the one forecast in SharePad.

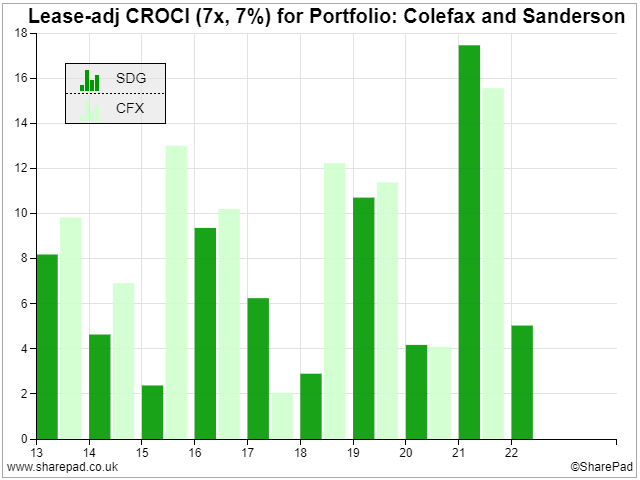

But cash is king, and in terms of Cash Return on Capital Invested (CROCI), the more conservative Colefax has usually done better in the past:

CROCI comparison. Colefax has yet to publish its results for 2022.

If you look up the price-earnings (PE) ratios in SharePad, it appears that Sanderson shares are much cheaper. Its PE ratio is 8.2, while Colefax’s is 24. But Colefax’s PE ratio is based on depressed profit in 2021. Its forecast PE is 8.6.

These valuations are surprisingly low. After all, with the exception of the pandemic years, both companies have earned decent if unspectacular returns.

Diagnosis: Loss of discipline

All good strategies start with a diagnosis, and then we need to learn what the company is doing about it.

Unfortunately, companies rarely share their diagnoses. It is tantamount to confessing weakness. We must reverse engineer Sanderson’s diagnosis from the company’s subsequent actions.

The changes at Sanderson started with the resignation of its seasoned chief executive John Sach in October 2018. The chairman followed in April 2019 when the company revealed that it had made 25% less profit than the year before.

The two men were replaced by two women, chief executive Lisa Montague, an external appointment, and chairman Dame Dianne Thompson. They are still running the business and the board respectively today.

The chief financial officer role has been less settled though. The company has had three in as many years.

After running the business for a year, the new team described its strategy in the annual report for the year to January 2020, which was to focus on:

- The individuality of its five brands

- Core products (wallpaper, fabric and paint)

- Core customers

- Key geographies (UK, Europe, USA)

- Investing in people

Focus is the essence of strategy, so what is perhaps most interesting about this five-point focus, is what it does not include.

It does not include inventing new brands or acquiring them. These are two things that Colefax is reluctant to do, and two things that Sanderson did. For example in 2012, Sanderson invented the Scion brand and in 2016 it acquired Clarke & Clarke, a mid-market brand.

In promising to give each brand its own strategy the company also stepped away from its umbrella Style Library brand.

This focus on core brands and geographies sounds so much like PZ Cussons’ turnaround strategy, I am wondering if there is a playbook for new managers of companies that have acquired too many brands and overcomplicated their operations.

I was one of two shareholders at Colefax’s AGM in 2016. There, chief executive David Green explained how it sought efficiency by minimising the number of new collections it launched annually (each one costing up to £1.5 million in pattern books and so on) and the number of Stock Keeping Units (SKUs or distinct items) it stocks.

More brands, and more products and patterns within those brands, means more SKUs, which increases the chances of having unsold stock at the end of the season.

I have no idea if he still does, but then Mr Green would conduct Colefax’s end-of-season sale personally (sometimes out of the back of his Range Rover if I remember correctly).

No doubt he had a keen awareness of the cost of stocking unpopular lines.

In her first annual report in 2020, Sanderson CEO Lisa Montagu explained: “On average during the past few years, around 55 new collections have been launched each year. We intended to reduce that to about 37 collections this year and, in light of the pandemic, this will be even fewer, at around 21.”

In the 2022 annual report, she elaborates: “Improving the efficiency of the business by reducing the number of stocked items (‘SKUs’) is an integral part of our strategy. Our focus has been on fewer, stronger collection launches to reduce the number of SKUs. Historically, only a proportion of them sold particularly well whilst others added to costs and inventory.”

Extrapolating from the strategy, I think Sanderson may have become somewhat unfocused and inefficient by 2019.

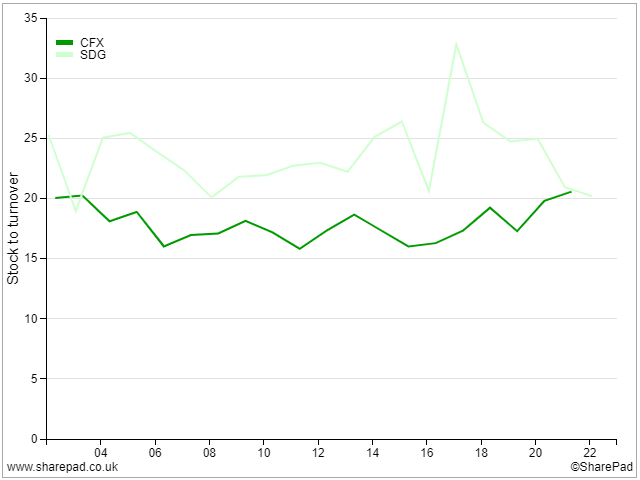

One way to test whether the strategy is working is to test whether the company is becoming more efficient at turning stock into turnover. We can do this by plotting the value of stock as a percentage of turnover.

A lower percentage means less stock is required to generate the same level of turnover and the company is more efficient.

Under the new strategy, Sanderson has brought the percentage of stock down to its historical lows of about 20% of turnover, which is another way of saying it used its stock five times in 2022. In 2019, stock was 25% of turnover. It used it less than four times.

Coincidentally five times is about the same level of efficiency as Colefax:

Mission accomplished

Sanderson’s results in 2022 were good. If we ignore the cost of amortising acquired intangible assets and restructuring in the year, return on capital was well above 20%, the company had net cash at the year-end, and its defined benefit pension scheme was in surplus.

One swallow does not necessarily make a summer, especially in the unusual circumstances of the pandemic, but arguably Sanderson has recovered its focus.

Even so, and despite its low valuation, I am resisting the notion of investing.

It is relatively straightforward, though not necessarily easy, to revive brands by focusing on them, but what happens then?

I prefer to hold shares indefinitely, which means for at least ten years and preferably much longer.

Once the gains from more focus are achieved the company can either take the conservative Colefax route or expand by launching new brands or acquiring them.

Everything I know about the fabric and wallpaper industries suggests this is difficult and may condemn Sanderson to a cycle of expansion followed by focus.

I have similar feelings of ambivalence towards PZ Cussons (despite owning shares in the company) and Portmeirion, collections of brands in health and beauty and homewares respectively that have experienced contemporaneous changes in management and similar changes in strategy to Sanderson.

Rather than owning companies that achieve scale by owning many brands, my still evolving understanding tilts me towards companies that can achieve scale with a single very popular brand.

Companies like Dr Martens, perhaps.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.