I like companies that boast significant net cash. My reasons include:

- Limited risk of funding difficulties should trouble strike;

- Management might be sensible by holding ‘rainy day’ money;

- The cash position may have resulted from superb profit generation, and;

- The share price could be less volatile (especially if the cash position represents a large part of the market cap).

How to screen for growth stocks

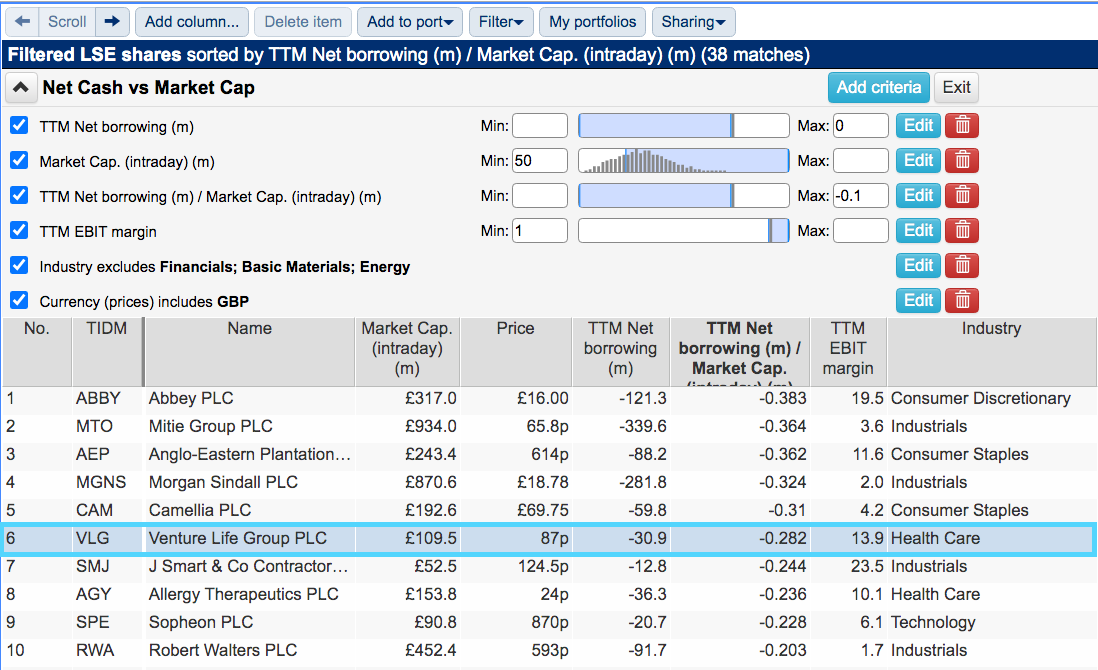

I therefore applied the following filter criteria to identify some reasonable cash-flush businesses:

- Trailing twelve-month net borrowings of no more than zero (i.e. a net cash position);

- A market cap of at least £50 million;

- Net cash of at least 10% of the market cap, and;

- A trailing twelve-month operating margin of at least 1% (to include only profitable companies).

I excluded financial companies as their cash balances often reflect client money or other restricted funds. I avoided miners and other resources shares as well.

I applied the criteria the other day and found 38 matches within SharePad:

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 21/04/21: Venture Life” filter within SharePad’s vibrant Filter Library. My instructions show you how.)

Among the companies identified were Character and Somero Enterprises.

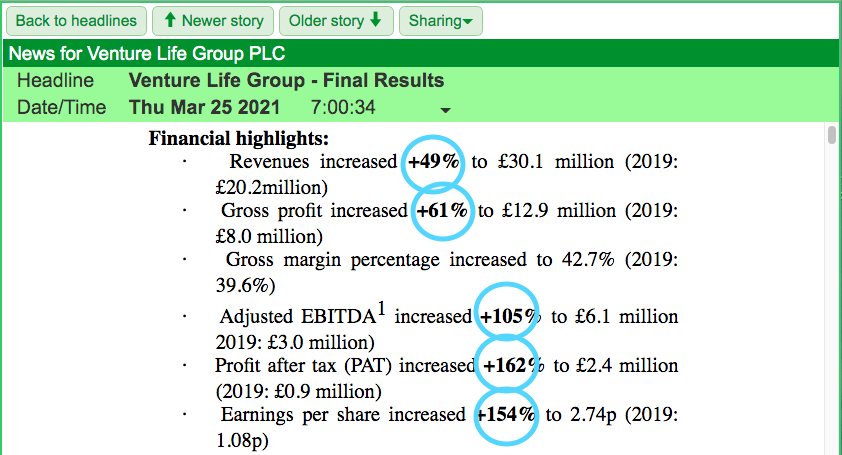

Venture Life attracted my attention because this company:

- Carried a significant 28% of its market cap as net cash;

- Operated within the generally favourable healthcare sector, and;

- Published impressive results last month:

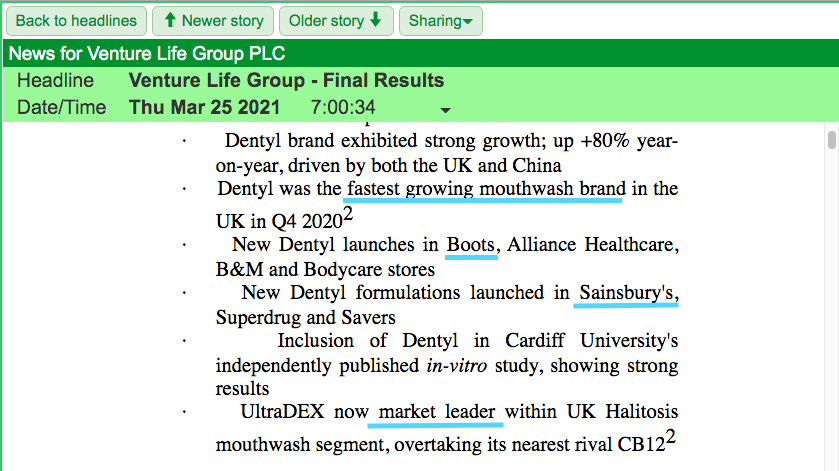

Further reading of the results showed branded products selling well at big-name retailers:

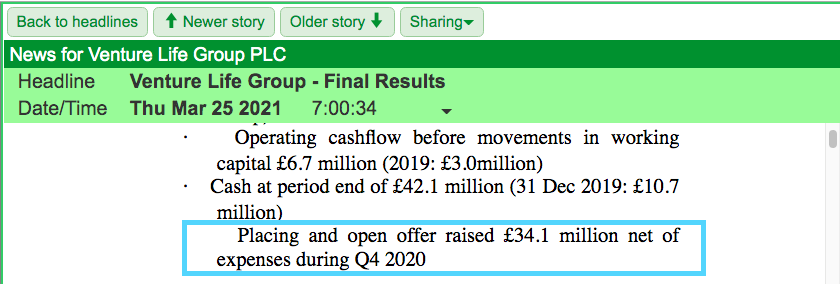

But the highlights also revealed where the cash position came from:

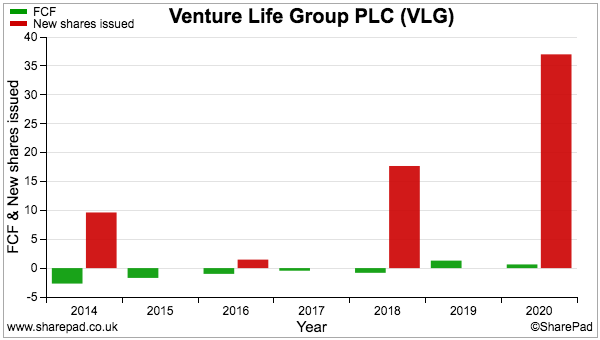

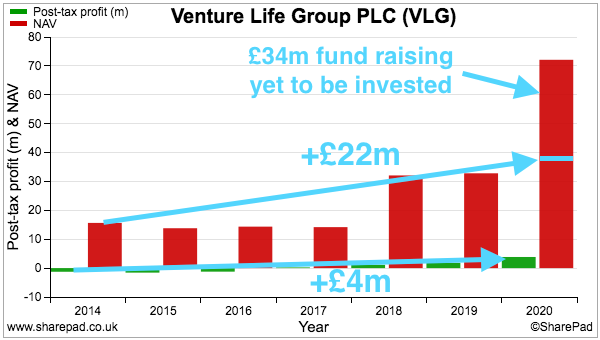

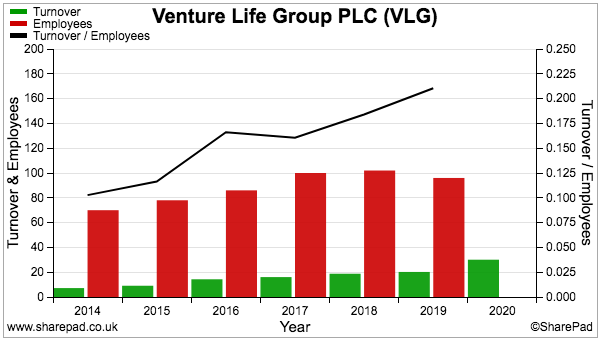

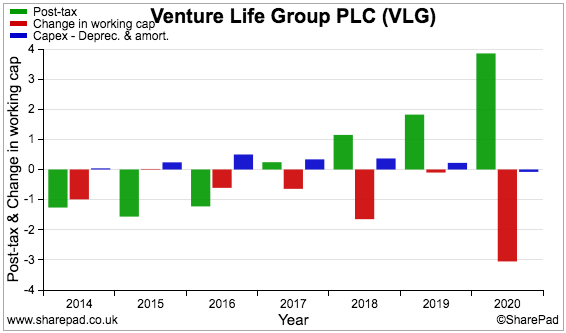

The chart below emphasises the scale of Venture’s £34 million fund raising, with new money raised from shares (red bars) dwarfing reported free cash flow (green bars):

A hefty cash position raised mostly from shareholders is not as ideal as a hefty cash position generated entirely from normal operations.

But cash is cash, so let’s take a closer look.

History of Venture Life

Venture’s chief executive, Jerry Randall, and chief commercial officer, Sharon Daly, established the group back in 2010 with a ‘buy and build’ strategy to create a healthcare products business

The first purchase involved a Finnish shampoo that treated hair loss, with subsequent small deals bringing in face creams, eye drops, make-up removers and food supplements.

Venture’s flotation during 2014 part-funded the purchase of an Italian manufacturing facility for £13 million. Venture then issued further shares to fund more acquisitions, with nearly £18 million raised during 2018 to complement the £34 million received last year.

Following the flotation, approximately £14 million has been spent acquiring:

- UltraDex, a specialist mouthwash for halitosis (2016);

- Dentyl, an everyday mouthwash (2018), and;

- PharmaSource, a Dutch business selling treatments for fungal infections (2020).

Management describes the ideal acquisition as a branded healthcare product that can be:

- Revitalised through improved marketing;

- Sold within additional countries;

- Enhanced through a wider product range, and;

- Manufactured in-house.

Dentyl offers a good example. This mouthwash has apparently been sold within the UK for 25 years, but under Venture’s ownership was the country’s fastest-growing mouthwash last year in part due to becoming available in Boots:

Company-owned brands such as Dentyl currently represent 50% of revenue, with the balance earned through the manufacture of third-party healthcare items.

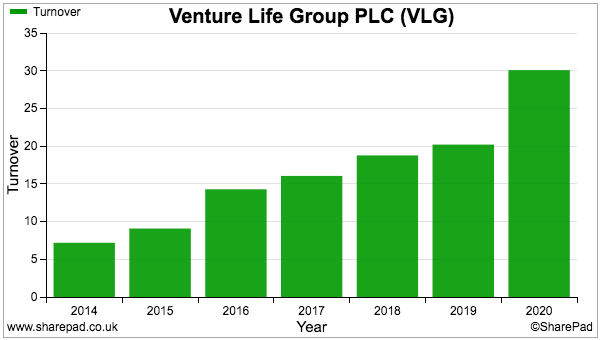

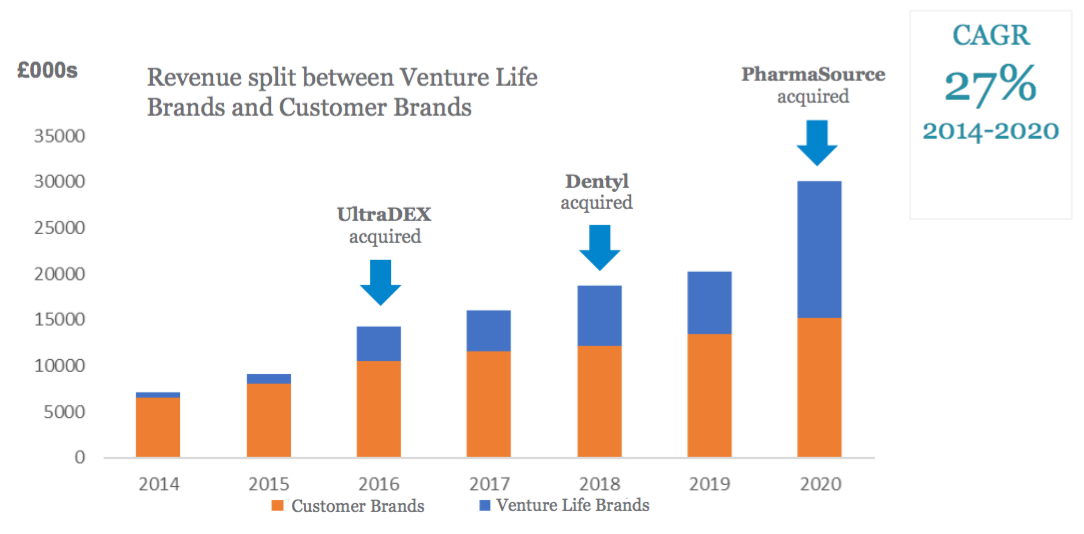

The acquisitions have propelled revenue higher…

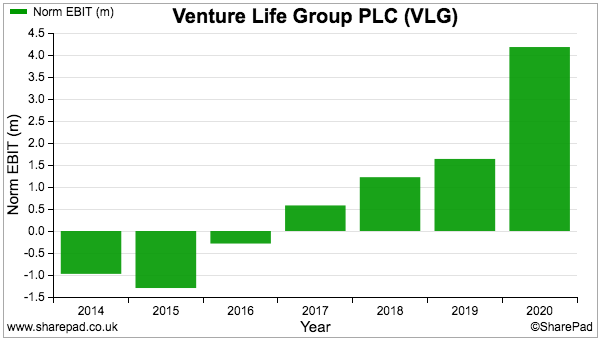

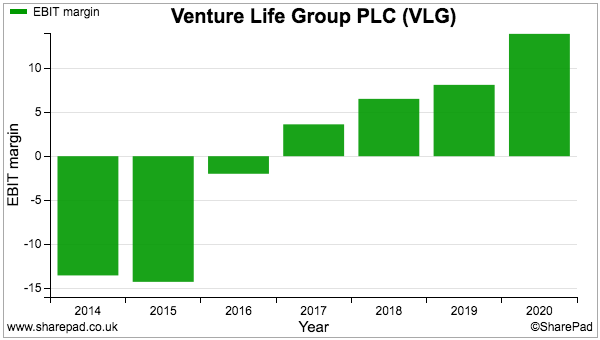

…and in turn converted losses into profit:

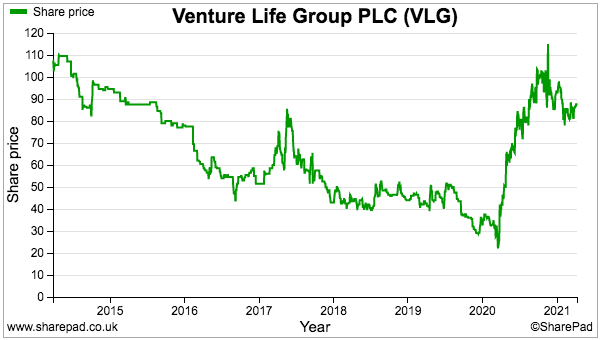

Note that the share price has not tracked the improved financials. Shareholders buying at the initial 109p have yet to break even:

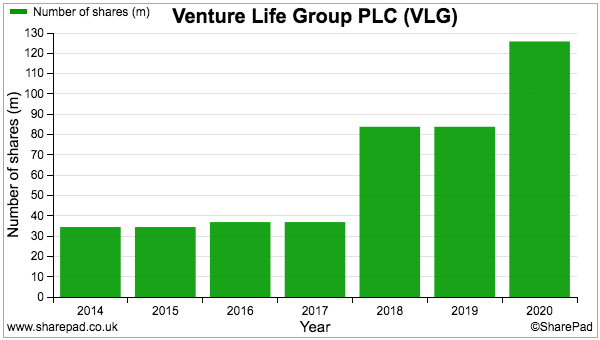

Hindering returns have been all the extra shares issued during the aforementioned fund raisings. The share count has quadrupled since the flotation:

The market cap at flotation was £26 million and was recently £110 million, which just goes to show how a more valuable business does not always translate into a more valuable share price.

Past acquisitions

Companies that grow by acquisition often carry greater risks. Potential dangers include:

- Paying far too much;

- Buying fundamentally troubled businesses;

- Integration problems and/or failure to extract benefits, and;

- Extra share dilution and/or onerous debt funding.

Venture’s deals so far do not seem obvious disasters. Revenue contributions from the acquired subsidiaries suggest the group has enjoyed some organic growth.

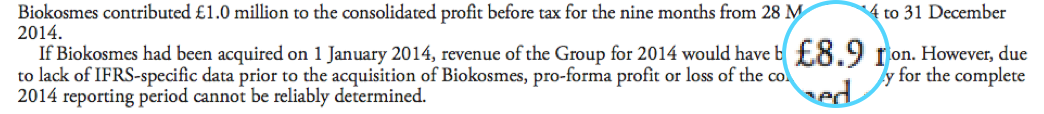

For example, the annual report small-print says the manufacturing facilities acquired at the flotation would have contributed full-year revenue of £8.9 million at the time of purchase…

…and last year this manufacturing division reported sales of £15.2 million.

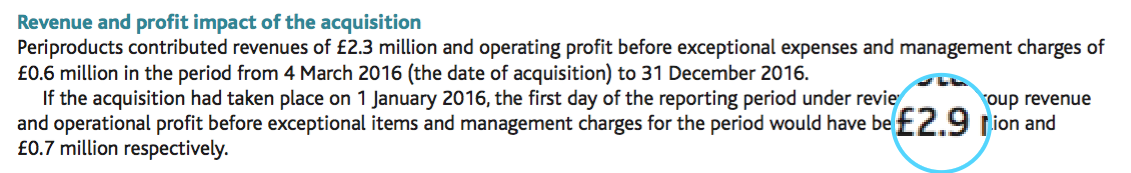

UltraDex meanwhile would have contributed full-year revenue of £2.9 million at the time of purchase…

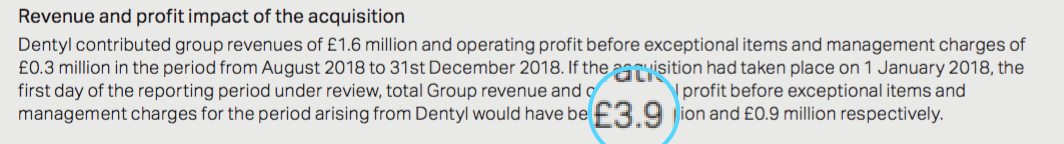

…while Dentyl would have contributed £3.9 million…

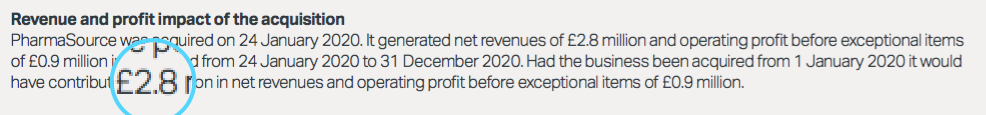

…and PharmaSource would have contributed £2.8 million:

Those initial contributions total £9.6 million, which compares to revenue of £10.1m that all three combined achieved last year.

A positive omen comes from comparing Venture’s earnings to its net asset value (or shareholder equity):

Between 2014 and 2020, reported earnings increased by £4 million while shareholder equity advanced by £22 million (excluding the £34 million raised last year).

Investing £22 million to receive an extra £4 million equates to a very respectable 18% return, which probably explains why investors handed over £34 million last year to secure more deals.

Future acquisitions

Last year’s £34 million fund raise was accompanied by useful commentary about acquisition valuations and likely target purchases.

The text below goes some way to explain the aforementioned 18% return on the extra equity invested:

“The Directors seek earnings accretive acquisitions in a target valuation range of 4x to 7x Ebitda where they believe there is an opportunity to generate both cost and revenue synergies.”

Buying at low, single-digit Ebitda multiples should typically lead to double-digit returns on investment.

Among Venture’s acquisition targets is the owner of “four brands whose main products are focused on oncology support therapies to treat the dermatological and oral side-effects of cancer treatments.”

Venture mooted a £5.5 million payment for this acquisition in exchange for sales of £3.5 million and estimated Ebitda of at least £1.2 million.

Another target is a “heritage brand in the UK and EU within the oral care market.” A price tag of £5 million was suggested for sales of £3 million and a margin “in excess of 30%”.

But the most intriguing target is a “well-known heritage dermatological brand and is widely marketed in the UK“. No sales or profit estimates were given, although the acquisition could be Venture’s largest yet at between £15 million and £20 million.

The target figures indicate a collective investment of approximately £30 million that I guess may bring in adjusted Ebidta of £5 million.

If Venture can revitalise any acquired brands in a manner similar to Dentyl, then perhaps the returns on the £30 million spent could in fact reach my earlier 18% calculation.

The following text within the same fund-raise announcement is very interesting. Venture somewhat boldly outlined the potential for greater economies of scale and very attractive margins:

“The Directors believe that the Fundraising together with sufficient leverage should allow the Group to target accretive acquisitions, with the potential to add significantly to its revenue and Ebitda and consider that an increase in Group revenue would enable the Company materially to increase its operating margin. In the medium term, the Directors aspire to create a business capable of generating £75 million of revenue with an operating margin of 25-30 per cent“

As company-branded sales (blue bars) have grown to represent a greater proportion of group revenue…

…so Venture’s operating margin has advanced:

Whether the operating margin reaches management’s 25%-plus aspiration, though, remains to be seen.

Also of significance is the doubling of revenue per employee (black line, right axis), which presently stands at a very useful £200,000-plus:

Such improvements to workforce productivity do suggest this business exhibits ‘scalable’ qualities.

Past performance and share sales

‘Buy and build’ strategies do not always work out, as Venture’s chief exec Jerry Randall can attest.

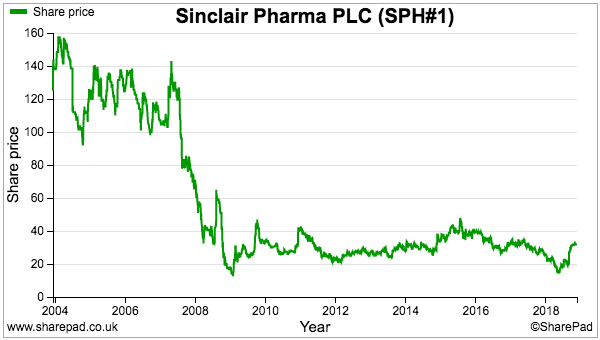

His previous job was finance director at Sinclair Pharma, which floated during 2003 and where the stated approach was:

“The sourcing and acquisition of late stage or fully developed innovative [pharmaceutical] products that have the potential to reach the marketplace within a relatively short time frame.”

Priced initially at 115p, Sinclair’s shares never recovered after announcing a product delay during 2007:

Years of losses eventually led to funding issues during 2008, with Mr Randall (and other directors) providing loans to the company — a situation I doubt was in the original ‘buy and build’ plan.

Venture may of course not suffer that same fate. This time around Mr Randall has steered clear of pharmaceutical treatments and their extended regulatory requirements:

“By intentionally developing products that are not classified as [pharmaceutical] drugs, the Group is able to avoid the significant capital and time expenditure required to develop and bring to market prescription drugs.”

Venture Life shares

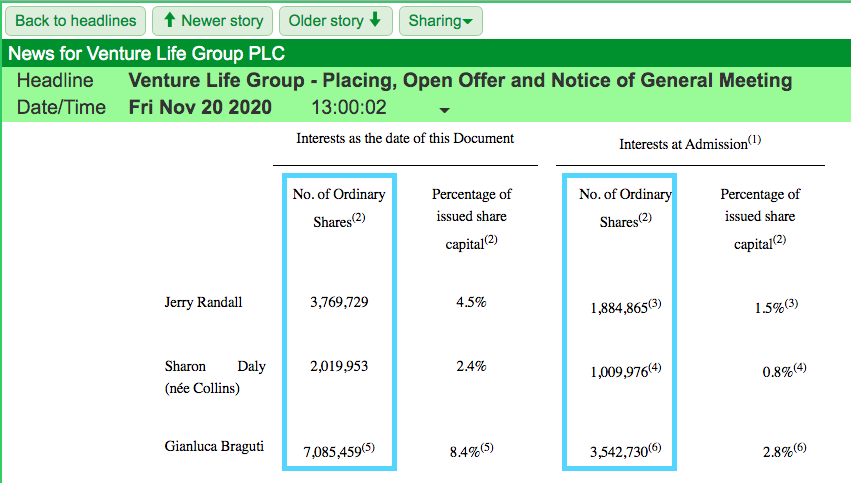

Note that Mr Randall (and the other Venture directors) were not keen to chip in with last year’s £34 million fund raise.

On the contrary, the lead executives sold 50% of their aggregate holding at the 90p placing price:

Management’s remaining £6 million/6% shareholding is not insignificant, but shareholders could rightly ask whether the board’s conviction is as high as it was.

SharePad does not reveal anything too untoward with the accounts, but I would highlight notable levels of profit (green bars) have on occasion been retained to expand working capital (red bars) rather than flow through as free cash:

Note also that Venture likes to report acquisition-related costs as ‘exceptional’, which is a debatable treatment for a ‘buy and build’ operator. Such expenditure has totalled £1 million during the last six years.

Valuation and summary

I confess Venture is not my ideal net cash company.

Yes, the group’s hefty cash position ought to limit difficulties should trouble strike. However, the money all looks earmarked for acquisitions and did not result from superb profit generation.

Everything essentially boils down to how the money raised is invested and the incremental earnings that can be generated.

Venture’s track record to date appears good, and economies of scale are emerging. But shareholders are relying on the deal pipeline flowing freely and (presumably) larger acquisitions integrating well.

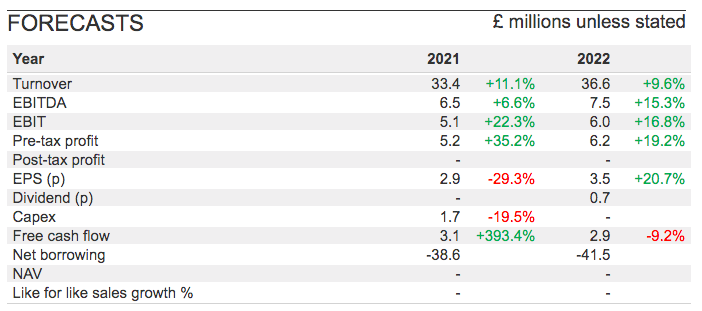

Although SharePad shows the following forecasts…

…these estimates may become very redundant when the next deal is announced.

A better approach is to think longer term and recall management’s aspiration to “create a business capable of generating £75 million of revenue with an operating margin of 25-30 per cent”.

That ambition implies earnings of approximately £15 million, which if achieved would support a lowly 7.3x multiple at the recent £110 million market cap.

Whether management’s ambition is realistic and reflected within the present valuation is something only you can decide. I would also consider the time for earnings to reach that potential £15 million and — most importantly — how further share issues will dilute any investment.

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Maynard writes about his portfolio at maynardpaton.com and hosts an investment discussion forum at quidisq.com. He does not own shares in Venture Life.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.