A company’s strategy should not just tell us what it wants to achieve, but why and how. Richard introduces a simple framework for analysing strategy and highlights a good strategy, and one that is more difficult to fathom.

My favourite book on strategy is “Good Strategy/Bad Strategy” by Richard Rumelt.

Rumelt is a professor of strategy in the United States, nicknamed “Strategy’s Strategist”. One of the comments on the following YouTube video of a talk Rumelt gave on the book says he is “to strategy what Mozart is to music!”:

Bad Strategy

Bad strategies, according to Rumelt, are aspirations, like delighting customers, or targets, like growing revenues by a certain percentage a year or profit margins to a certain level. You see this kind of thing all the time.

These are “things we think are nice”, a wishlist; they are not strategy because they do not tell us how the company is going to achieve its aspirations and they do not tell us what challenge the company is trying to overcome.

They just tell us what the company wants to be. If we do not know the why and how, we are not in a good position to evaluate whether the company is likely to succeed.

My routine technique for finding new companies to investigate is to filter a list of all the Shares listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) for desirable financial statistics in SharePad. Then I order the resulting list with the companies that have published their annual reports recently near the top.

Often the next step is to download the PDF of the annual report and search it for “strategy”. If I cannot find one, I may well move on to the next company in my list.

Last week I dismissed Vitec, one of a number of shares I was thinking about researching. Vitec makes a wide variety of products for video content makers, from hobbyists to filmmakers. My search for the company’s strategy found three strategic priorities:

- Organic growth

- Margin improvement

- Mergers and Acquisitions

These are all aspirations. In the smallprint there are some indications of how the company plans to achieve them, but often they do not rise above the generic things most companies do.

Vitec will achieve growth by inventing new products and investing in its fastest growing businesses. It will improve margins by becoming more efficient. It will evaluate acquisition opportunities to grow and to increase its technological capabilities.

In other words it will slug it out against competitors, improving its products as they improve theirs, cutting costs as they cut theirs, and it will acquire more businesses and do the same thing with them. The most interesting aspect is Vitec’s apparent thirst for technology, which may indicate its direction of travel.

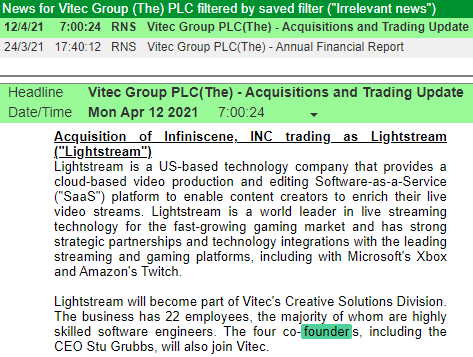

This Monday, Vitec announced that it had acquired Lightstream, which operates cloud-based software that allows gamers to enrich and stream video. The business is loss-making but develops technology and has a growing subscription base in a hot market currently unserved by Vitec.

Source: SharePad.

It could be a bold strategic decision; Vitec already operates a streaming video distribution platform.

But the company is best known for equipment like camera bags, tripods and lighting. On the same day Vitec announced the Lightstream acquisition, it announced another, a company that manufactures LED lighting for film sets, perhaps a better fit for its more traditional businesses.

I see glimpses of strategy, but to my mind they are incoherent. The strategy looks like a dog’s dinner, a term Rumelt uses.

Good strategy

This is how Rumelt defines strategy: “A strategy is a coherent mix of policy and action designed to surmount a difficult challenge.”

That might seem like a bit of a mouthful, but every word is important. The kernel of a good strategy has three components:

- Diagnosis – the nature of the challenge

- Guiding policy – the basic approach to solving the problem

- Coherent action – focused action to achieve the guiding policy and overcome the challenge

Unlike aspirations, each of these aspects of strategy requires decisions so that everybody in the organisation knows how the company is going to achieve its objectives. When you can see a company making hard decisions, that is prima facie evidence of good strategy.

The professor illustrates this point in the video and book with examples from Hannibal (the Carthaginian general) to Nvidia (the chip designer). I am going to include an example closer to home. I wrote about it in my last article.

If my description of Howden Joinery’s strategy in that article was clear, it is partly because Howdens articulates its strategy very well, and it is partly because when I first researched the company I had Rumelt’s framework to help me understand it.

Although I did not use the framework in my article, all the elements are there. Howdens was founded by Matthew Ingle, who only recently retired from the company. Ingle was previously trade managing director at Magnet, another kitchen supplier. Magnet, like many other kitchen suppliers, operated retail showrooms and trade counters.

Ingle realised this was a problem. His diagnosis was that by selling kitchens to both retail and trade customers, kitchen suppliers could not keep their pricing confidential. That meant trade customers could not decide their own mark-ups. In a sense retail showrooms were competing against their own trade customers.

So Howdens made a hard decision. It decided to turn away the business of retail customers so it could offer trade customers confidential pricing. That is its guiding policy. I know this is Howdens’ guiding policy because it is not just in the description of Howdens’ strategy in the annual report. It is on the front page of the report. It is on the side of the trucks. And it is on the depot signage.

Howdens does not hide its guiding policy. It is on the side of the trucks. Source: Howdens.com

Once Ingle had decided on his guiding policy the rest of the strategy fell into place. Since the company was only going to serve small builders, it could tailor its service to them in many ways, from the location of the depots, to the amount of credit it offered them, and the amount of stock it held. Rivals could not offer the same level of service to trade customers because they were, at the same time, trying to satisfy you and me.

Howdens both piggy-backed and enabled the trend towards more complicated fitted kitchens, and it became the UK’s biggest supplier.

There is another reason Howdens’ strategy is so easy to articulate, and why I am so confident in it, apart from the fact that the company tells us about it at every opportunity. The strategy is very well established. Howdens was founded in 1995 and it is still rolling it out now.

New strategy

It is much harder to evaluate a new strategy. Professor Rumelt’s advantage is he can get inside companies as an adviser while they are developing their strategies. From the outside, things are often less obvious.

Back in 2019 I wrote that PZ Cussons was at something of a turning point. The company, which owns a number of famous personal care and beauty brands like Carex, Imperial Leather, and St Tropez, had lost its way.

Much has happened since, most significantly the appointment of a new chief executive whose first job was to deal with the impact of the pandemic.

This March, he unveiled PZ Cussons’ new strategy and in my next article I will be attempting to work out the diagnosis, guiding policy, and coherent actions.

I am hoping it will not be a dog’s dinner. Simplicity, focus, and hard choices will be on my mind.

Wish me luck!

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.