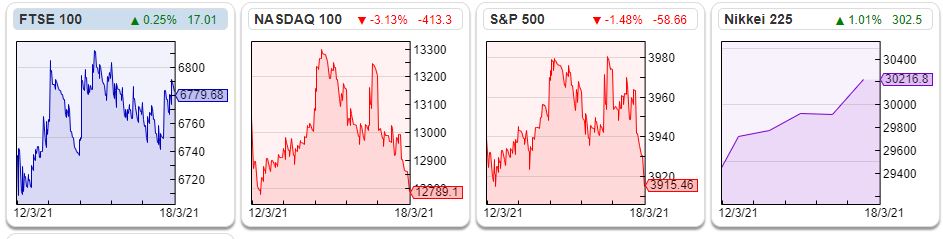

Last week James Anderson of Baillie Gifford announced that he is to step down from running the Scottish Mortgage IT. Tom Slater will continue running SMIT and Lawrence Burns, who published the article Why it is usually a mistake to sell your winners in the FT earlier this month, will become deputy portfolio manager with immediate effect. SMIT has enjoyed phenomenal success, however one interpretation is that we are close to the top of the market cycle in “disruptive growth”. Though SMIT has invested in many good businesses, valuations of equities in the fund are increasingly hard to justify. Certainly, it’s hard for me to believe the next 5 years will be like the last 5 years; even the best fund managers and best companies go through difficult patches.

SMIT owns shares in the Collison brother’s Stripe, which last week became the most valuable private company in the world, based on the most recent $600m series H funding round which valued the company at a $95bn. Series H – are they trying to go through the alphabet all the way to Z before they IPO? The $600m shows that they don’t really need the money to fund growth. They are using the demand from investors to set higher and higher private valuations rounds. The press release said that, despite the pandemic, only 14% of commerce takes place online today. Stripe is a payments platform, which should enjoy increasing returns from scale. The company said enterprise revenue (Stripe’s largest business) was doubling year on year.

The benefits of platforms and “fly wheels” with positive feedback are now well understood, but it wasn’t always the case. There’s a book* about the Santa Fe Institute and Brian Arthur, a Belfast born heterodox economist. Arthur, who came from a background in engineering, understood feedback loops and amplification. “Don’t worry” his Berkeley economics teacher reassured him “increasing returns situations are extremely rare, they don’t last very long.” The norm is diminishing returns. Neo-classical economists “knew” that competition drives down excess returns. Brian Arthur really struggled to have “increasing returns” accepted – journal editors would tell him that “increasing returns” wasn’t economics.

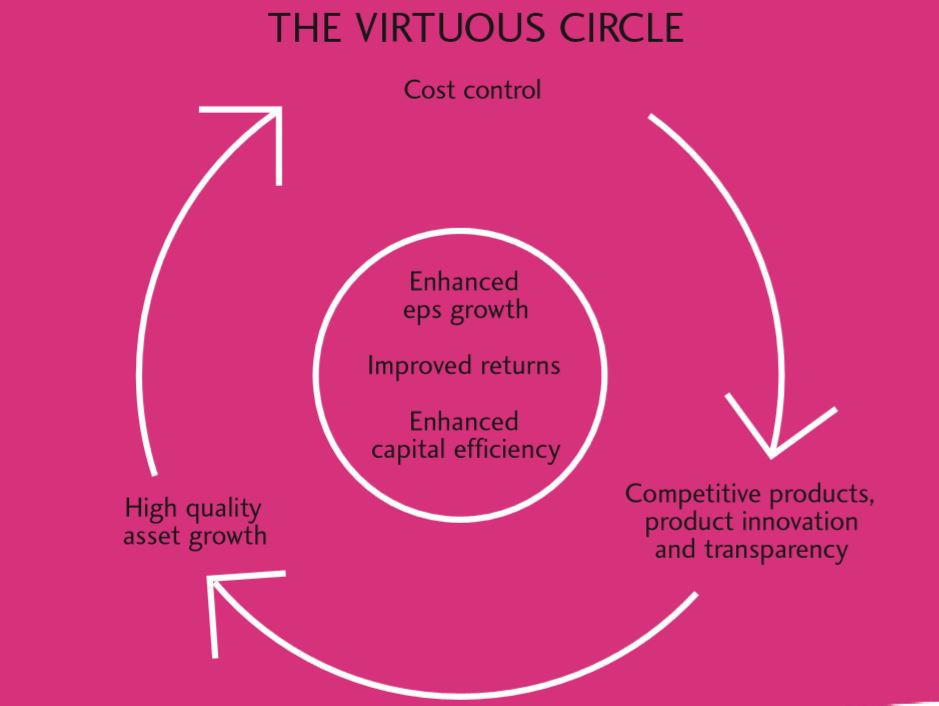

These ideas are now well accepted, but I’m wondering if we haven’t swung too far the other way? Northern Rock claimed to have a virtuous circle of asset growth -> cost control -> competitive products (see below).

In a sense this was true; for 10 years NRK punched well above its weight, the lender’s mortgage market share was over a fifth of the entire UK net mortgage market, and RoE was easily above 20%, just before the bank failed. At the start of 2007 Baillie Gifford were the largest shareholder in NRK too.

So even if a company does have a virtuous circle strategy with increasing returns, feedback loops can often reverse from positive to negative very quickly; the strategy hits the rocks and is holed below the waterline.

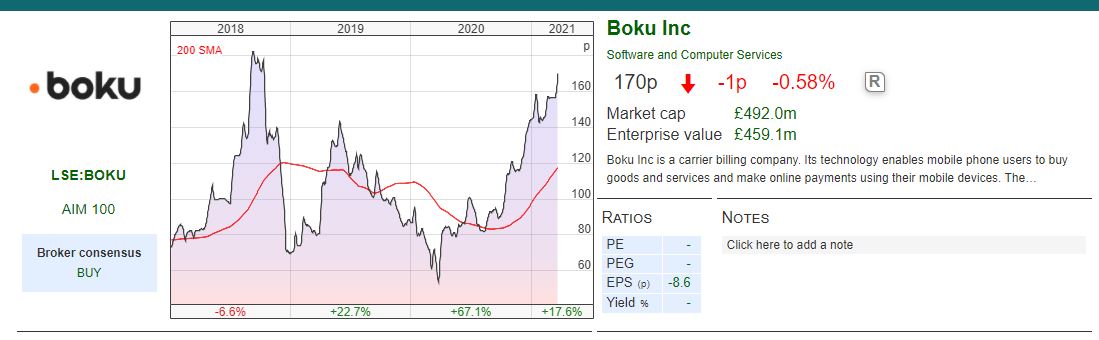

This week I look at a couple of Direct Carrier Billing (DCB) companies: Bango and Boku which both reported FY Dec 2020 results. DCBs allow people to pay for items by using their mobile phone and adding the cost to their bill (either pre-pay or monthly contract) rather than use banking infrastructure. Companies make money with a revenue share model: each transaction, DCBs and mobile phone companies take a small percentage. There are no fixed fees.

I think payments is another sector that goes on many people’s “too hard” pile, but may reward time invested in really understanding the story. I’ve noticed that management of both companies do not make it easy to find a reconciliation of statutory profits to cash from operations, which raises a red flag for me. They are also both trading on roughly 12x revenue, which suggests that investors have high expectations for the future. Some of my best performing investments have come from doing the work to understand a company or sector, then waiting until the price fell to what I considered a more reasonable valuation and entry point.

Boku does seem to be a platform, with exclusive relationships with many large retailers: Apple, Facebook, Sony and Spotify. But in their core niche market (they describe as a niche of a niche) revenue growth looks limited, and the company needs to expand into mobile wallets and digital identity to justify the valuation.

Bango on the other hand is smaller (perhaps a niche, of a niche, of a niche?) and has demonstrated impressive revenue growth in 2020, but is subscale and has struggled for profitability despite a gross margin above 95%. It may have turned the corner; following 15 years (15 years!) of losses, FY 2020 results showed a £600K profit on continuing operations and BGO is now forecast by their broker to grow revenue at +20% this year. Bango are selling customer payment data to app developers, so it is essential to understand both the regulatory environment and competition from adtech and other payment businesses.

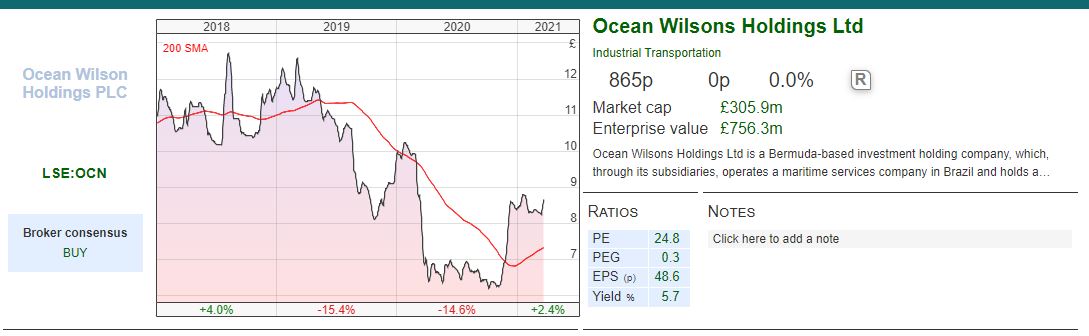

But first I look at Ocean Wilson, the Brazilian maritime logistics business. Though ports are “old economy” businesses, they share the characteristics of platforms, taking a percentage toll on trade, and costs are relatively fixed but assets are more tangible (shipping vessels and container terminal quays rather than software). Revenue fluctuates with global trade, the Brazilian economy and the commodity cycle, all of which are outside of the control of management. During the “commodity super cycle” 15 years ago this looked a very attractive business, because revenue was growing on a relatively fixed cost base. More recently the share price has been in the doldrums because revenue has fallen every year since FY 2013. But I’m hoping now that oil, copper and other commodities seem to be gaining momentum that performance will improve.

Ocean Wilsons FY Dec 2020

This holding company owns a 58% interest in Wilson Sons (Brazilian ports and maritime services) and a 100% ownership in an investment subsidiary (Ocean Wilsons Investments Ltd) reported FY Dec 2020 results. Wilson Sons was set up in the Brazilian port of Salvador by two Scottish brothers, Edward and Fleetwood Pellow Wilson in 1837.

Group revenue was down by -13% y-o-y, and PBT was down -21% to $48m. Basic eps was 109.5c down -17% and the dividend was flat at 70c per share. Net debt was $398m or £286m vs current market cap of £305m, though this did not include an additional $212m as part of a 50% joint venture. Also, it is worth noting that while Profit After Tax was $48m, currency movements resulted in a “below the line” charge of $52m. This is the correct accounting treatment, but investors should be aware the net asset value fell -5% from $786m to $743m after this charge and the dividend were paid.

Around 2/3 of the $398m debt is linked to the US dollar, as a significant portion of the Group’s commodity pricing is also denominated in dollars. Through 2020 the BRL fell 29% against the USD from R$4.03 at 1 January 2020 to R$5.20 at the year end.

Wilson Sons results The weaker Brazilian Real seems to be responsible for most of the weakness in the results; in local currency maritime services revenue was +13%, but in US dollars down -13% to $353m. Towage was up +8% to $182m, and port services revenue was down sharply by -25% to $150m due partly to Covid affecting global trade and partly oil and gas activity reduced when the oil price collapsed in the first half. They own 50% of an offshore vessels joint venture, recorded on the balance sheet at a cost of $26m, which was loss making $4.2m due also to oil and gas weakness. This had 16 offshore support vessels under contract vs a total fleet of 23. The vessels not under contract are available in the Brazilian spot market or laid up until the market improves.

In October 2020, they finished a US$110 million investment project which extended the Salvador container terminal’s quay to 800 metres. This means that two super-post-Panamax ships can birth simultaneously, which will increase their capacity and improve operational efficiency.

Outlook Management expect Brazilian exports to rise due to the depreciation of the BRL and a recovery in the global economy. They do say that despite the recovering oil price the Brazilian offshore oil and gas market is expected to remain soft. I think that this is “deep water”, hence more expensive than other oil fields. It is worth noting that the Brazilian economy is rather fragile, unemployment is high, daily Covid-19 cases reached over 90,000 this week, yet inflation above 5% has precipitated the Central Bank to hike interest rates by 75bp to 2.75%.

Investment Management The group’s investment portfolio (OWIL) was worth $310m end of Dec 2020, up +10.9% net of fees in the year. I have written before that the mix of hedge funds the group invest in has done poorly versus an S&P 500 index tracker. Over a 10-year view OWIL net of fees is up +47%, whereas the S&P 500 increased +199% over the same time period. The management commentary makes much of investing in Pershing Square which achieved 85.5% returns in 2020, as Bill Ackman bought a credit protection hedge which benefitted from market falls, before calling the turn and investing in Chipotle and Starbucks. However, at the end of the year Pershing Square was just 2% of OWIL NAV. Perhaps management like going to lunch with star hedge fund managers? The impression given is that they are certainly not trying to optimise returns for minority shareholders.

Valuation At the end of December the market value for the OCN Group’s holding of 41.4m shares (57.8%) of Wilson Sons quoted on the Brazilian and Luxembourg stock exchanges was worth US$362m, which is the equivalent of US$10.22 (£7.48) per Ocean Wilsons share. That is just the holding company’s share of the ports business. Adding to that the market value per share of the investment portfolio (OWIL $8.77 per share) gives a net asset value per Ocean Wilsons Holdings share of US$19.00 (£13.89). This compares to Ocean Wilsons Holdings share price of £8.45 at the end of last year, and 865p currently. This 39% discount to NAV is greater than in previous years – I can’t help thinking that if management invested OWIL in low-cost index trackers then we would see the discount to NAV narrow.

Opinion For me this business has an attractive combination of value and quality. Between 2003 and 2013 Ocean Wilsons 14 bagged, peaking at £14.52, but the most recent decade has not been so kind with the shares roughly halving. Brazil had a deep recession in 2016, as well as a commodity price crash. I hope that a recovery in global trade and the increased capacity that management have invested in should mean that eventually revenue growth drives a re-rating.

BOKU FY Dec 2020

Boku is a DCB that connects digital merchants through its platform to Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) and payment wallets in Asia. This allows someone to subscribe to merchants (eg Spotify) and charge it through to their phone bill. They point out what they do is niche, with limited competition because merchants prefer to deal with only one (large) DCB, so they have an exclusive relationship with Apple, Facebook, Sony and Spotify.

Revenue was up +12% to $56m. Excluding both a prior year non-recurring item of $3.3m and the acquisition of Estonian based Fortumo in July last year, which contributed $4.5m of revenue, gives +8% organic revenue growth. On page 6, management talk about +38% organic growth in the value processed through their platform, which if comparable to that +8% organic revenue growth implies either i) margin pressure ii) change in mix.

The company reported adjusted EBITDA of $15.3m, double the previous year, but a pre-tax loss of $17m, mainly due to a $20.8m goodwill impairment from an acquisition (Danal bought on 1st Jan 2019) in the identity space, which they wrote down.

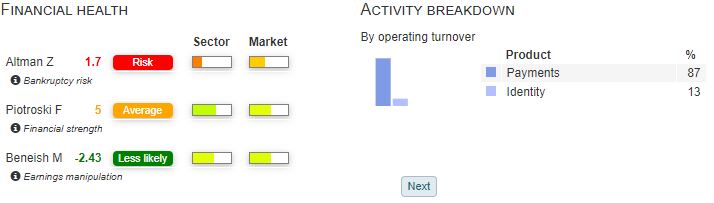

Receivables versus sales As a cross check for whether adjusted EBITDA is reasonable, I tend to look at “cash from operations”, which is $31m for Boku. At first glance this is pleasing, but I’m disappointed the company don’t provide a reconciliation with statutory profits in the cashflow statement: it’s hidden away in note 22 of the accounts, and shows a $29.6m increase in trade and other receivables. Excluding movements in working capital “cash from operations” was a far less impressive $11.5m vs $6.1m last year. Looking at the face of the balance sheet, trade and other receivables were very high, $92m vs revenue of $56m. In the Annual Report a “Key Audit Matter” is mentioned around revenue recognition because of receipts from MNOs, and gross payables to merchants accrue at the year end. I think that would be the first question that I would ask the company, if I was meeting management. That is presumably why the Altman Z score on the next page highlights the company as risky, despite $61.3m of cash on the balance sheet, up from $34.7m in 2019 and FY 2020 CashRoCI was 37% (top 5% of the market according to SharePad).

Story stock Putting concerns over the large receivables number aside, the investment case on Boku is about the future revenue growth story. Boku admit that their profitable niche of DCB is expensive compared to other payment methods (eg cards, paypal) but DCB is a good way for websites to recruit new customers, because it requires less friction than paying with a card. Management say that they have helped merchants recruit more than 50m customers and suggest that the average merchant on the Boku platform is connected to 32 out of the 204 carriers on its platform, which implies some room to expand in DCB.

But the other, much larger opportunity is mobile wallets. Boku say that cards, while growing absolutely, are losing payment market share to mobile wallets and “buy now pay later” businesses (eg Max Levchin’s Affirm). A mobile wallet can be used in a physical store, by using a QR code. In Asia mobile wallets account for a greater proportion of e-commerce spending than debit and credit cards combined, according to the company. Boku have launched Grabpay and Gopay, and are now targeting existing relationships with merchants, and are winning business from “card first” payment processors such as Adyen and Worldpay. There’s a good summary by Jon Prideaux, the Chief Exec from January this year available here

Institutions Vitruvian Partners (via Build Lux Holdco) own 7.4%, Danske Bank 6.5%, Blackrock 5.1%, Swedbank Robur 4% and Aberdeen 4%.

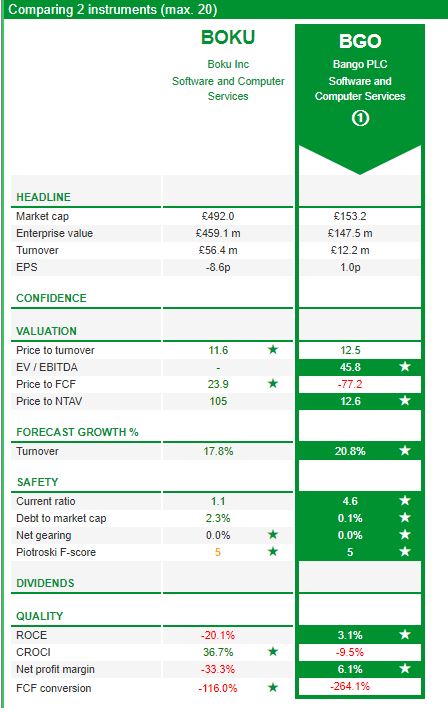

Opinion On the next page I’ve used SharePad’s “compare” tab with Boku v Bango. Both are trading on 12x multiple of sales, yet Boku has much better CROCI. I would ignore the RoCE of -20%, because that’s driven by the goodwill impairment writedown of Danal. This doesn’t feel like the time to be chasing either of these expensive tech platforms, but perhaps the price will fall to a more reasonable entry point?

Bango FY Dec 2020

This smaller but faster growing DCB reported revenues +70% to £12.2m. The company recorded a small £607k PBT from continuing operations versus a £2.6m loss last year. There was a £3.9m profit from discontinued operations, though I think that includes a £4.8m disposal gain (see below). BGO had net cash of £3.1m. Trade and other receivables were £3.2m, which seems a more usual number relative to revenues than Boku. The increase was £991k, which is understandable in the context of +70% revenue growth this year, but still noteworthy in the context of £607k PBT on continuing operations.

Bango earns payment revenue from transactions processed through the Bango Platform and data monetization revenue from the insights provided to app developers. The way the company likes to explain the model is Facebook and Google earn advertising dollars by targeting ad spend on what we “like” or search for. Yet there are a lot of items we might like or search for that we don’t actually want to buy. Instead, Bango uses the payments data to allow targeted ad-spend on what people spend money on. Bango don’t have the exclusive relationships with large merchants that Boku can claim, but the Mobile Network Operators (MNO) partner with them, because the MNOs unlock a new revenue stream by selling “audiences” via Bango to app developers (who then earn money from people downloading their apps and making “in-app purchases”). These audiences are built out of transaction data from the MNO billing relationship, so that app developers know who the 5% of customers are who make in-app purchases and they can be targeted.

There’s an 11-minute video here that gives a highlight of FY 2020 results and summarises the business. It contains a nice quote from SoftBank saying “We look forward to benefiting from Bango data insights and to accelerate the growth of our new business”.

Bango don’t have any easy way to download their Annual Report PDF. Instead the Annual Report appears on their website and is harder to read. You would think that a technology company would be able to make available a PDF of the Annual Report on their website!

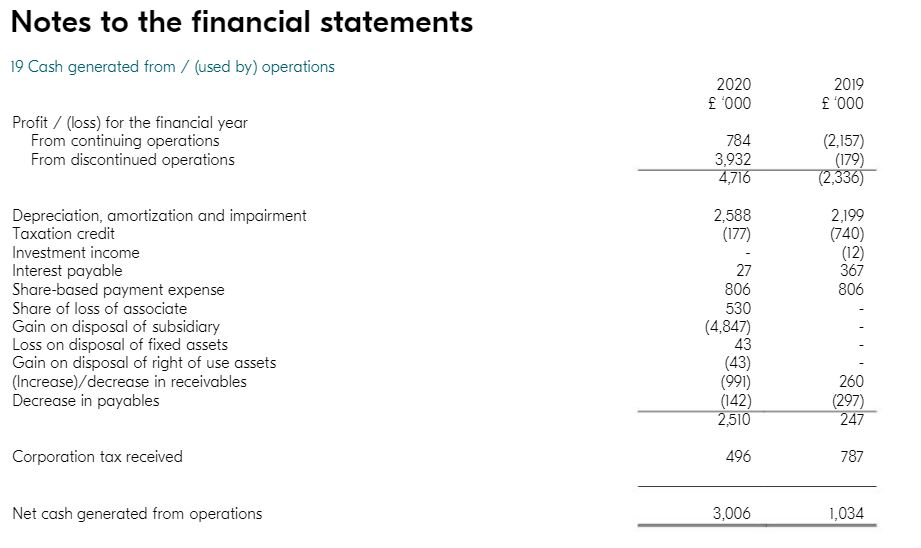

Like Boku, Bango don’t show their full cashflow statements. The “cash from operations” £2.5m is not reconciled with statutory profit in their RNS. Bango go one better than Boku (or one worse, depending on how you look at it) and don’t include the reconciliation anywhere in their press release. Instead readers have to look at note 19 of their Annual Report. I’ve reproduced it here:

Bango management have broken out the profit from discontinued operations £3.9m, which was from the disposal of 60% of Bango Deep Ltd. To be clear, management deducting the £4.8m gain on sale from statutory profits in the cashflow from operations is the correct accounting treatment, but it seems odd to me that they don’t split out the £4.8m gain on sale anywhere in the P&l. The remaining 40% of Bango Deep that they have retained has been renamed New Deep, and been accounted for as an associate. So I think that Bango Deep was loss-making and the £3.9m of profit from discontinued operations includes £4.8m gain on disposal netted off against losses and disposal costs?

Outlook statement The company talks about future growth in 2021 and beyond, helped by (it believes) a permanent switch to online commerce. Martin Flitton adds more colour after speaking to management on his blog here. Across payments, Bango is processing 50% more subscriptions than it was a year back. Management point to new users added in January which is also 50% above the peak lockdown number in H1 last year.

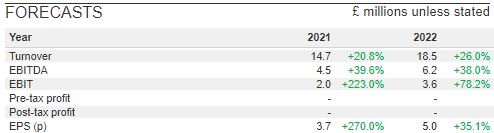

Forecasts SharePad shows EPS forecasts of 3.7p FY 2021F and 5p in 2022F. That implies a PER of 55x this year, falling to 41x next year. I’d be reluctant to pay such a full multiple for a company that’s disappointed in the past.

Institutions Liontrust at 15%, and Herald at 10.7%, who both tend to own “expensive tech growth” in their process, are the largest shareholders. Odey 10.1%, Hargreave Hale 9.8%.

Opinion If Bango can now generate 20-30% revenue growth on a fixed cost base for several years, then that would justify the valuation. That’s a big if though. I do worry that payments is all about scale, and there are much larger players in the sector. I think this is worth following and over time if the company can deliver, then I’d put my concerns about the valuation aside.

Bruce Packard

Notes

The author owns shares in Ocean Wilsons

*Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos by M Wardrop https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07WVV5J2R/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_E078BSKCE985G08GEJ9F

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Weekly Commentary 22/03/21: Ports and platforms

Last week James Anderson of Baillie Gifford announced that he is to step down from running the Scottish Mortgage IT. Tom Slater will continue running SMIT and Lawrence Burns, who published the article Why it is usually a mistake to sell your winners in the FT earlier this month, will become deputy portfolio manager with immediate effect. SMIT has enjoyed phenomenal success, however one interpretation is that we are close to the top of the market cycle in “disruptive growth”. Though SMIT has invested in many good businesses, valuations of equities in the fund are increasingly hard to justify. Certainly, it’s hard for me to believe the next 5 years will be like the last 5 years; even the best fund managers and best companies go through difficult patches.

SMIT owns shares in the Collison brother’s Stripe, which last week became the most valuable private company in the world, based on the most recent $600m series H funding round which valued the company at a $95bn. Series H – are they trying to go through the alphabet all the way to Z before they IPO? The $600m shows that they don’t really need the money to fund growth. They are using the demand from investors to set higher and higher private valuations rounds. The press release said that, despite the pandemic, only 14% of commerce takes place online today. Stripe is a payments platform, which should enjoy increasing returns from scale. The company said enterprise revenue (Stripe’s largest business) was doubling year on year.

The benefits of platforms and “fly wheels” with positive feedback are now well understood, but it wasn’t always the case. There’s a book* about the Santa Fe Institute and Brian Arthur, a Belfast born heterodox economist. Arthur, who came from a background in engineering, understood feedback loops and amplification. “Don’t worry” his Berkeley economics teacher reassured him “increasing returns situations are extremely rare, they don’t last very long.” The norm is diminishing returns. Neo-classical economists “knew” that competition drives down excess returns. Brian Arthur really struggled to have “increasing returns” accepted – journal editors would tell him that “increasing returns” wasn’t economics.

These ideas are now well accepted, but I’m wondering if we haven’t swung too far the other way? Northern Rock claimed to have a virtuous circle of asset growth -> cost control -> competitive products (see below).

In a sense this was true; for 10 years NRK punched well above its weight, the lender’s mortgage market share was over a fifth of the entire UK net mortgage market, and RoE was easily above 20%, just before the bank failed. At the start of 2007 Baillie Gifford were the largest shareholder in NRK too.

So even if a company does have a virtuous circle strategy with increasing returns, feedback loops can often reverse from positive to negative very quickly; the strategy hits the rocks and is holed below the waterline.

This week I look at a couple of Direct Carrier Billing (DCB) companies: Bango and Boku which both reported FY Dec 2020 results. DCBs allow people to pay for items by using their mobile phone and adding the cost to their bill (either pre-pay or monthly contract) rather than use banking infrastructure. Companies make money with a revenue share model: each transaction, DCBs and mobile phone companies take a small percentage. There are no fixed fees.

I think payments is another sector that goes on many people’s “too hard” pile, but may reward time invested in really understanding the story. I’ve noticed that management of both companies do not make it easy to find a reconciliation of statutory profits to cash from operations, which raises a red flag for me. They are also both trading on roughly 12x revenue, which suggests that investors have high expectations for the future. Some of my best performing investments have come from doing the work to understand a company or sector, then waiting until the price fell to what I considered a more reasonable valuation and entry point.

Boku does seem to be a platform, with exclusive relationships with many large retailers: Apple, Facebook, Sony and Spotify. But in their core niche market (they describe as a niche of a niche) revenue growth looks limited, and the company needs to expand into mobile wallets and digital identity to justify the valuation.

Bango on the other hand is smaller (perhaps a niche, of a niche, of a niche?) and has demonstrated impressive revenue growth in 2020, but is subscale and has struggled for profitability despite a gross margin above 95%. It may have turned the corner; following 15 years (15 years!) of losses, FY 2020 results showed a £600K profit on continuing operations and BGO is now forecast by their broker to grow revenue at +20% this year. Bango are selling customer payment data to app developers, so it is essential to understand both the regulatory environment and competition from adtech and other payment businesses.

But first I look at Ocean Wilson, the Brazilian maritime logistics business. Though ports are “old economy” businesses, they share the characteristics of platforms, taking a percentage toll on trade, and costs are relatively fixed but assets are more tangible (shipping vessels and container terminal quays rather than software). Revenue fluctuates with global trade, the Brazilian economy and the commodity cycle, all of which are outside of the control of management. During the “commodity super cycle” 15 years ago this looked a very attractive business, because revenue was growing on a relatively fixed cost base. More recently the share price has been in the doldrums because revenue has fallen every year since FY 2013. But I’m hoping now that oil, copper and other commodities seem to be gaining momentum that performance will improve.

Ocean Wilsons FY Dec 2020

This holding company owns a 58% interest in Wilson Sons (Brazilian ports and maritime services) and a 100% ownership in an investment subsidiary (Ocean Wilsons Investments Ltd) reported FY Dec 2020 results. Wilson Sons was set up in the Brazilian port of Salvador by two Scottish brothers, Edward and Fleetwood Pellow Wilson in 1837.

Group revenue was down by -13% y-o-y, and PBT was down -21% to $48m. Basic eps was 109.5c down -17% and the dividend was flat at 70c per share. Net debt was $398m or £286m vs current market cap of £305m, though this did not include an additional $212m as part of a 50% joint venture. Also, it is worth noting that while Profit After Tax was $48m, currency movements resulted in a “below the line” charge of $52m. This is the correct accounting treatment, but investors should be aware the net asset value fell -5% from $786m to $743m after this charge and the dividend were paid.

Around 2/3 of the $398m debt is linked to the US dollar, as a significant portion of the Group’s commodity pricing is also denominated in dollars. Through 2020 the BRL fell 29% against the USD from R$4.03 at 1 January 2020 to R$5.20 at the year end.

Wilson Sons results The weaker Brazilian Real seems to be responsible for most of the weakness in the results; in local currency maritime services revenue was +13%, but in US dollars down -13% to $353m. Towage was up +8% to $182m, and port services revenue was down sharply by -25% to $150m due partly to Covid affecting global trade and partly oil and gas activity reduced when the oil price collapsed in the first half. They own 50% of an offshore vessels joint venture, recorded on the balance sheet at a cost of $26m, which was loss making $4.2m due also to oil and gas weakness. This had 16 offshore support vessels under contract vs a total fleet of 23. The vessels not under contract are available in the Brazilian spot market or laid up until the market improves.

In October 2020, they finished a US$110 million investment project which extended the Salvador container terminal’s quay to 800 metres. This means that two super-post-Panamax ships can birth simultaneously, which will increase their capacity and improve operational efficiency.

Outlook Management expect Brazilian exports to rise due to the depreciation of the BRL and a recovery in the global economy. They do say that despite the recovering oil price the Brazilian offshore oil and gas market is expected to remain soft. I think that this is “deep water”, hence more expensive than other oil fields. It is worth noting that the Brazilian economy is rather fragile, unemployment is high, daily Covid-19 cases reached over 90,000 this week, yet inflation above 5% has precipitated the Central Bank to hike interest rates by 75bp to 2.75%.

Investment Management The group’s investment portfolio (OWIL) was worth $310m end of Dec 2020, up +10.9% net of fees in the year. I have written before that the mix of hedge funds the group invest in has done poorly versus an S&P 500 index tracker. Over a 10-year view OWIL net of fees is up +47%, whereas the S&P 500 increased +199% over the same time period. The management commentary makes much of investing in Pershing Square which achieved 85.5% returns in 2020, as Bill Ackman bought a credit protection hedge which benefitted from market falls, before calling the turn and investing in Chipotle and Starbucks. However, at the end of the year Pershing Square was just 2% of OWIL NAV. Perhaps management like going to lunch with star hedge fund managers? The impression given is that they are certainly not trying to optimise returns for minority shareholders.

Valuation At the end of December the market value for the OCN Group’s holding of 41.4m shares (57.8%) of Wilson Sons quoted on the Brazilian and Luxembourg stock exchanges was worth US$362m, which is the equivalent of US$10.22 (£7.48) per Ocean Wilsons share. That is just the holding company’s share of the ports business. Adding to that the market value per share of the investment portfolio (OWIL $8.77 per share) gives a net asset value per Ocean Wilsons Holdings share of US$19.00 (£13.89). This compares to Ocean Wilsons Holdings share price of £8.45 at the end of last year, and 865p currently. This 39% discount to NAV is greater than in previous years – I can’t help thinking that if management invested OWIL in low-cost index trackers then we would see the discount to NAV narrow.

Opinion For me this business has an attractive combination of value and quality. Between 2003 and 2013 Ocean Wilsons 14 bagged, peaking at £14.52, but the most recent decade has not been so kind with the shares roughly halving. Brazil had a deep recession in 2016, as well as a commodity price crash. I hope that a recovery in global trade and the increased capacity that management have invested in should mean that eventually revenue growth drives a re-rating.

BOKU FY Dec 2020

Boku is a DCB that connects digital merchants through its platform to Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) and payment wallets in Asia. This allows someone to subscribe to merchants (eg Spotify) and charge it through to their phone bill. They point out what they do is niche, with limited competition because merchants prefer to deal with only one (large) DCB, so they have an exclusive relationship with Apple, Facebook, Sony and Spotify.

Revenue was up +12% to $56m. Excluding both a prior year non-recurring item of $3.3m and the acquisition of Estonian based Fortumo in July last year, which contributed $4.5m of revenue, gives +8% organic revenue growth. On page 6, management talk about +38% organic growth in the value processed through their platform, which if comparable to that +8% organic revenue growth implies either i) margin pressure ii) change in mix.

The company reported adjusted EBITDA of $15.3m, double the previous year, but a pre-tax loss of $17m, mainly due to a $20.8m goodwill impairment from an acquisition (Danal bought on 1st Jan 2019) in the identity space, which they wrote down.

Receivables versus sales As a cross check for whether adjusted EBITDA is reasonable, I tend to look at “cash from operations”, which is $31m for Boku. At first glance this is pleasing, but I’m disappointed the company don’t provide a reconciliation with statutory profits in the cashflow statement: it’s hidden away in note 22 of the accounts, and shows a $29.6m increase in trade and other receivables. Excluding movements in working capital “cash from operations” was a far less impressive $11.5m vs $6.1m last year. Looking at the face of the balance sheet, trade and other receivables were very high, $92m vs revenue of $56m. In the Annual Report a “Key Audit Matter” is mentioned around revenue recognition because of receipts from MNOs, and gross payables to merchants accrue at the year end. I think that would be the first question that I would ask the company, if I was meeting management. That is presumably why the Altman Z score on the next page highlights the company as risky, despite $61.3m of cash on the balance sheet, up from $34.7m in 2019 and FY 2020 CashRoCI was 37% (top 5% of the market according to SharePad).

Story stock Putting concerns over the large receivables number aside, the investment case on Boku is about the future revenue growth story. Boku admit that their profitable niche of DCB is expensive compared to other payment methods (eg cards, paypal) but DCB is a good way for websites to recruit new customers, because it requires less friction than paying with a card. Management say that they have helped merchants recruit more than 50m customers and suggest that the average merchant on the Boku platform is connected to 32 out of the 204 carriers on its platform, which implies some room to expand in DCB.

But the other, much larger opportunity is mobile wallets. Boku say that cards, while growing absolutely, are losing payment market share to mobile wallets and “buy now pay later” businesses (eg Max Levchin’s Affirm). A mobile wallet can be used in a physical store, by using a QR code. In Asia mobile wallets account for a greater proportion of e-commerce spending than debit and credit cards combined, according to the company. Boku have launched Grabpay and Gopay, and are now targeting existing relationships with merchants, and are winning business from “card first” payment processors such as Adyen and Worldpay. There’s a good summary by Jon Prideaux, the Chief Exec from January this year available here

Institutions Vitruvian Partners (via Build Lux Holdco) own 7.4%, Danske Bank 6.5%, Blackrock 5.1%, Swedbank Robur 4% and Aberdeen 4%.

Opinion On the next page I’ve used SharePad’s “compare” tab with Boku v Bango. Both are trading on 12x multiple of sales, yet Boku has much better CROCI. I would ignore the RoCE of -20%, because that’s driven by the goodwill impairment writedown of Danal. This doesn’t feel like the time to be chasing either of these expensive tech platforms, but perhaps the price will fall to a more reasonable entry point?

Bango FY Dec 2020

This smaller but faster growing DCB reported revenues +70% to £12.2m. The company recorded a small £607k PBT from continuing operations versus a £2.6m loss last year. There was a £3.9m profit from discontinued operations, though I think that includes a £4.8m disposal gain (see below). BGO had net cash of £3.1m. Trade and other receivables were £3.2m, which seems a more usual number relative to revenues than Boku. The increase was £991k, which is understandable in the context of +70% revenue growth this year, but still noteworthy in the context of £607k PBT on continuing operations.

Bango earns payment revenue from transactions processed through the Bango Platform and data monetization revenue from the insights provided to app developers. The way the company likes to explain the model is Facebook and Google earn advertising dollars by targeting ad spend on what we “like” or search for. Yet there are a lot of items we might like or search for that we don’t actually want to buy. Instead, Bango uses the payments data to allow targeted ad-spend on what people spend money on. Bango don’t have the exclusive relationships with large merchants that Boku can claim, but the Mobile Network Operators (MNO) partner with them, because the MNOs unlock a new revenue stream by selling “audiences” via Bango to app developers (who then earn money from people downloading their apps and making “in-app purchases”). These audiences are built out of transaction data from the MNO billing relationship, so that app developers know who the 5% of customers are who make in-app purchases and they can be targeted.

There’s an 11-minute video here that gives a highlight of FY 2020 results and summarises the business. It contains a nice quote from SoftBank saying “We look forward to benefiting from Bango data insights and to accelerate the growth of our new business”.

Bango don’t have any easy way to download their Annual Report PDF. Instead the Annual Report appears on their website and is harder to read. You would think that a technology company would be able to make available a PDF of the Annual Report on their website!

Like Boku, Bango don’t show their full cashflow statements. The “cash from operations” £2.5m is not reconciled with statutory profit in their RNS. Bango go one better than Boku (or one worse, depending on how you look at it) and don’t include the reconciliation anywhere in their press release. Instead readers have to look at note 19 of their Annual Report. I’ve reproduced it here:

Bango management have broken out the profit from discontinued operations £3.9m, which was from the disposal of 60% of Bango Deep Ltd. To be clear, management deducting the £4.8m gain on sale from statutory profits in the cashflow from operations is the correct accounting treatment, but it seems odd to me that they don’t split out the £4.8m gain on sale anywhere in the P&l. The remaining 40% of Bango Deep that they have retained has been renamed New Deep, and been accounted for as an associate. So I think that Bango Deep was loss-making and the £3.9m of profit from discontinued operations includes £4.8m gain on disposal netted off against losses and disposal costs?

Outlook statement The company talks about future growth in 2021 and beyond, helped by (it believes) a permanent switch to online commerce. Martin Flitton adds more colour after speaking to management on his blog here. Across payments, Bango is processing 50% more subscriptions than it was a year back. Management point to new users added in January which is also 50% above the peak lockdown number in H1 last year.

Forecasts SharePad shows EPS forecasts of 3.7p FY 2021F and 5p in 2022F. That implies a PER of 55x this year, falling to 41x next year. I’d be reluctant to pay such a full multiple for a company that’s disappointed in the past.

Institutions Liontrust at 15%, and Herald at 10.7%, who both tend to own “expensive tech growth” in their process, are the largest shareholders. Odey 10.1%, Hargreave Hale 9.8%.

Opinion If Bango can now generate 20-30% revenue growth on a fixed cost base for several years, then that would justify the valuation. That’s a big if though. I do worry that payments is all about scale, and there are much larger players in the sector. I think this is worth following and over time if the company can deliver, then I’d put my concerns about the valuation aside.

Bruce Packard

Notes

The author owns shares in Ocean Wilsons

*Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos by M Wardrop https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07WVV5J2R/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_E078BSKCE985G08GEJ9F

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.