One way to invest during the pandemic is to consider shares that have climbed higher as the market has dropped.

Such companies may well be ‘safe havens’ — businesses that are coping well with the lockdown, or perhaps even benefitting from the crisis.

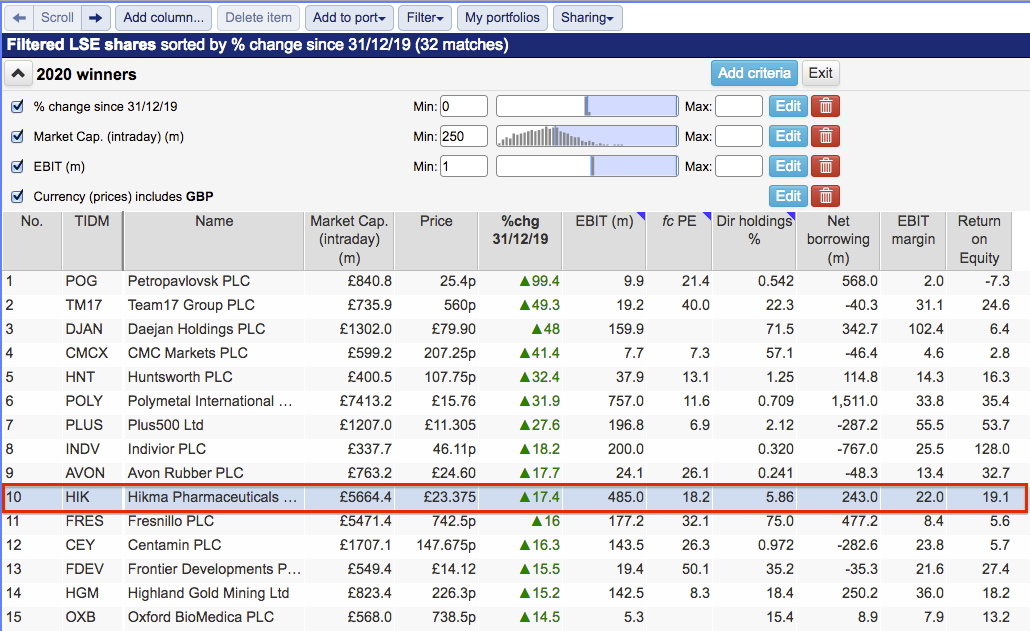

I applied the following simple criteria within SharePad to identify potential ‘pandemic-proof’ names:

- A share-price change this year of 0% or more;

- A market cap of £250 million or more, and;

- A profit of £1m or more;

I wanted only reasonably sized and profitable companies in my shortlist. Note that my screening included only shares denominated in GBP, which therefore excluded the obscure foreign companies traded on the LSE:

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 13/05/20: Hikma Pharmaceuticals” filter within SharePad’s helpful Filter Library. My instructions show you how.)

SharePad returned 32 matches, including Boohoo, Domino’s Pizza and Dotdigital.

However, the largest gainers of the year so far fell into four broad sectors:

- Gold miners, such as Petropavlovsk and Polymetal;

- Spread-bet operators, such as CMC Markets and Plus500;

- Computer game developers, such as Frontier Developments and Team17, and;

- Healthcare firms, such as Hikma Pharmaceuticals and Indivior.

You can probably understand why those four sectors might be relatively resilient to the pandemic.

I selected Hikma Pharmaceuticals for further investigation because I preferred healthcare to the other three sectors. In addition:

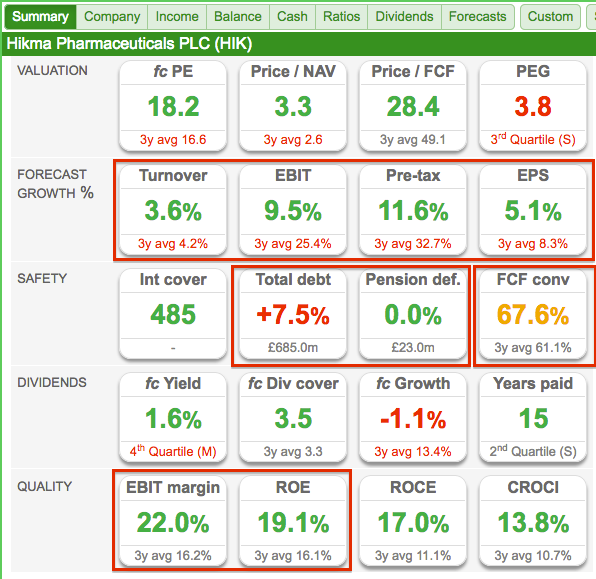

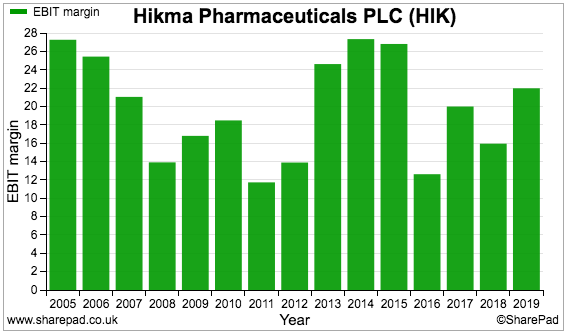

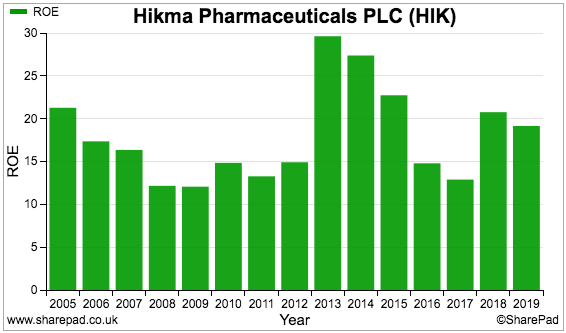

- The 22% margin and 19% return on equity (ROE) appeared good;

- Profit was twice the level of debt;

- The forecast 18x P/E did not appear too extreme, and;

- The directors owned a useful shareholding.

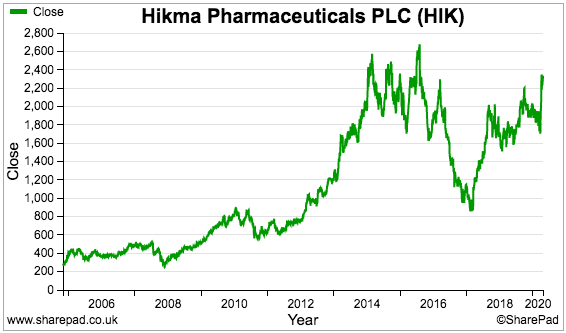

Hikma’s share-price rally this year has extended the gains seen since the lows of early 2017:

The price now is not far off the £26 highs registered during 2016 to support a £5.7 billion market cap.

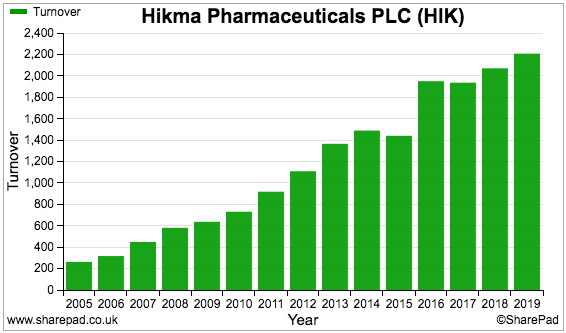

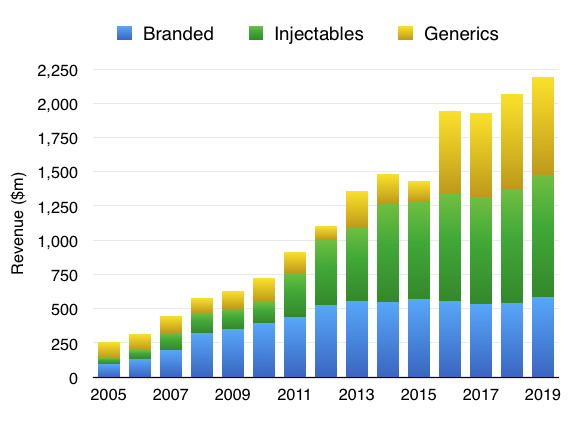

Hikma’s revenue shows a lovely upwards trend:

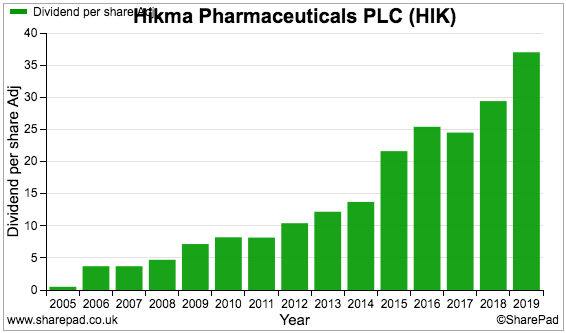

And so does the dividend:

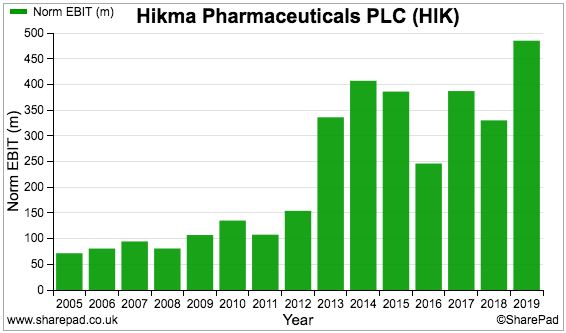

‘Normalised’ profit — that is, profit excluding exceptional items and other company adjustments — has been up and down during the last few years:

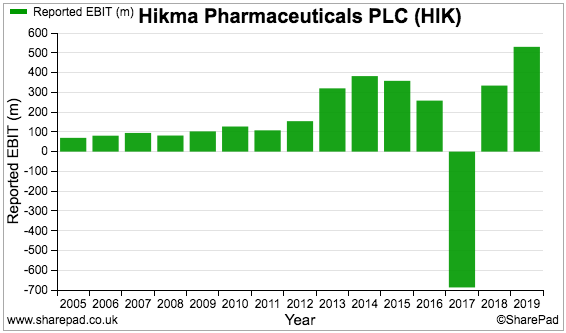

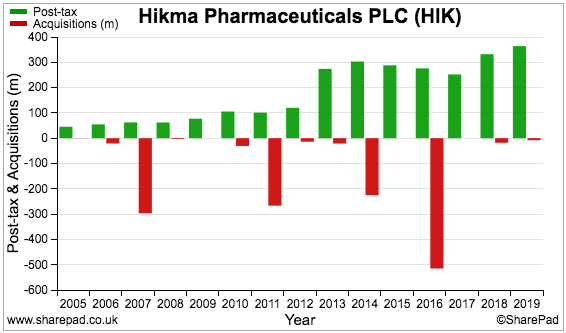

But reported profit — which includes exceptional items and other company adjustments — shows a thumping loss for 2017:

We need to discover what happened back then.

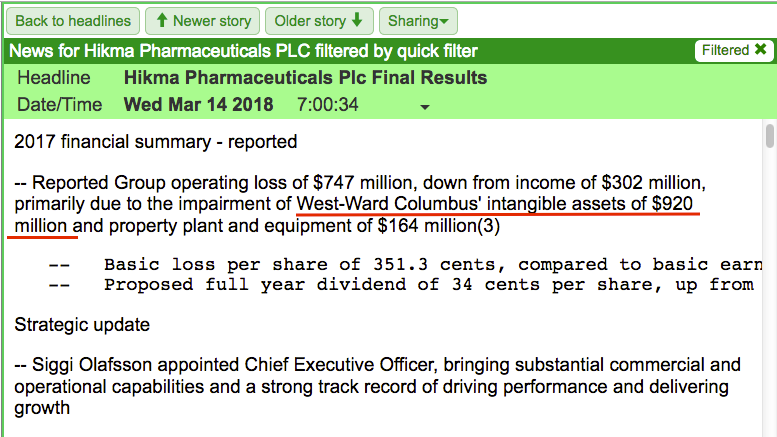

SharePad can quickly locate the 2017 results, the first headline for which refers to a $920 million impairment relating to something called West-Ward Columbus:

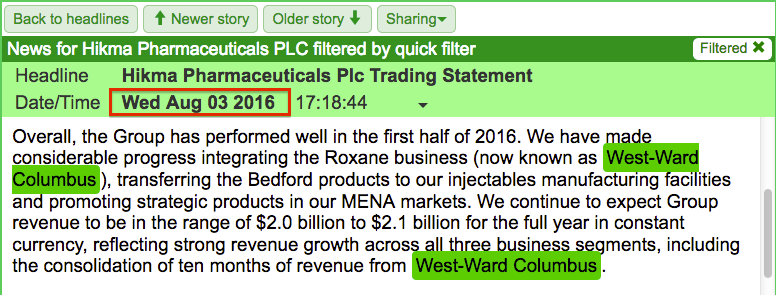

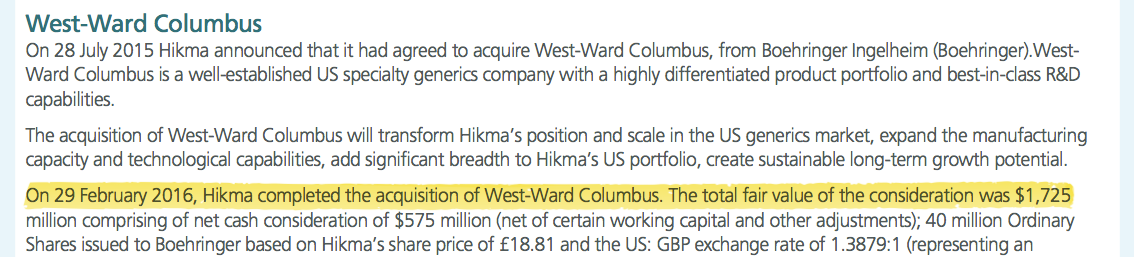

The earliest mention of West-Ward Columbus within Hikma’s RNS history occurred during 2016:

Oh dear — this does not look good. The RNSs above tell us Hikma purchased West-Ward Columbus during 2016, and within two years suffered that $920 million write-off.

The 2016 annual report confirms the purchase cost $1.7 billion — so more than half was wasted:

We had better check Hikma’s history of acquisition expense:

Cash flow spent on acquisitions (red bars) comes to $1.3 billion. Furthermore, the 2016 annual report reveals $1 billion was raised by issuing new shares to help acquire West-Ward Columbus.

A total of $2.3 billion has therefore been spent on acquisitions following the 2005 flotation. In comparison, total post-tax profit before exceptional items and other adjustments (green bars) comes to $2.7 billion.

Conclusion: Hikma has spent substantial amounts buying other companies, which needs to be considered when recalling those lovely revenue and dividend charts.

Let’s dig a little into what Hikma does.

The business of Hikma Pharmaceuticals

Samih Darwazah had already established two businesses before founding Hikma Pharmaceuticals during 1978. His first venture involved selling apples aged 6, his second was owning a pharmacy during his 20s.

Then followed a decade working for Eli Lilly, after which Mr Darwazah opened a small factory in his home country of Jordan to manufacture generic pharmaceuticals.

Within a few years, Hikma began manufacturing patented pharmaceuticals under license. The firm expanded quickly by selling its various products throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

(Source: samihdarwazah.com)

By 1991 Mr Darwazah had instructed his eldest son to lead Hikma into the United States. A milestone occurred a few years later when Hikma’s facilities in New Jersey and the operation in Jordan received US regulatory approval.

These days the States represent 61% of Hikma’s $2.2 billion revenue, with 33% spread throughout the Middle East and Africa and the balance earned from Europe.

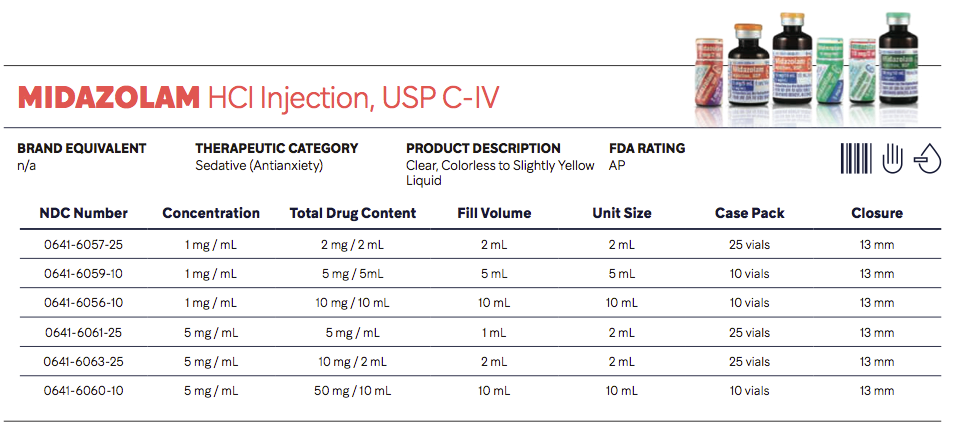

Hikma divides its operations into three divisions: Generics, Injectables and Branded. All three sell a mix of generic and manufactured-under-licence pharmaceuticals:

- Generics: tablets, capsules and powder-based treatments;

- Injectables: injection treatments;

- Branded: Hikma-branded generic tablets sold mostly in the Middle East and Africa.

At the last count the group manufactured approximately 700 different products and is apparently a leading supplier of nasal sprays. Hikma’s Injectables catalogue and non-Injectables catalogue provide a comprehensive round-up of the treatments sold.

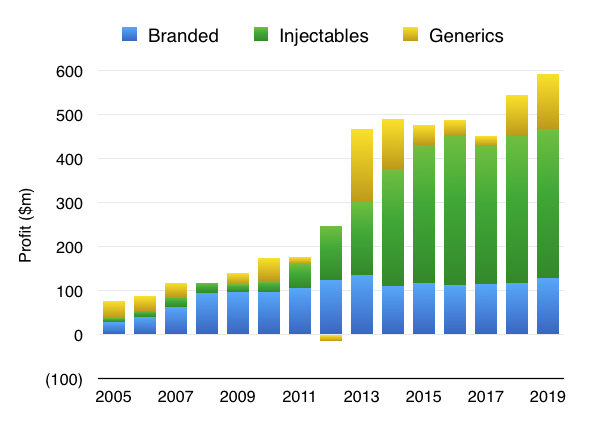

The Injectables division has expanded at the greatest pace since the group’s 2005 flotation:

Injectables are also the dominant profit contributors:

From what I understand, injection treatments are more lucrative than conventional generic tablets because the manufacturing process is more complex and the testing requirements are more involved. Hikma claims almost 60% of its Injectable products have five competitors or less.

I should add that Mr Darwazah led the business until 2007, remained non-exec chairman until 2014 and passed away during 2015. His sons Said and Mazen are currently Hikma’s lead executives and between them own a notable 9%/£517 million shareholding.

Write-offs, pipeline and legal problems

The aforementioned $920 million write-off relating to West-Ward Columbus lifted the lid on the challenges that generic pharmaceutical businesses face.

Hikma said when admitting the write-off (my bold):

“The increasingly competitive dynamics of the US market, including intense pricing pressure, had a material impact on our Generics business and, in particular, on West-Ward Columbus. This was further impacted by the delay in approval for our generic version of Advair Diskus®. As a result of these headwinds, we have had to take an impairment related to the West-Ward Columbus business to reflect our updated view of the fair value of this business.”

I suppose bouts of “intense pricing pressure” are not surprising when Hikma essentially manufactures a copycat product that could be replicated by another generic manufacturer.

The Generics division has not been very predictable. It has twice reported an underlying loss since 2005 and, when profitable, the division’s margin has fluctuated anywhere between 4% and 62%.

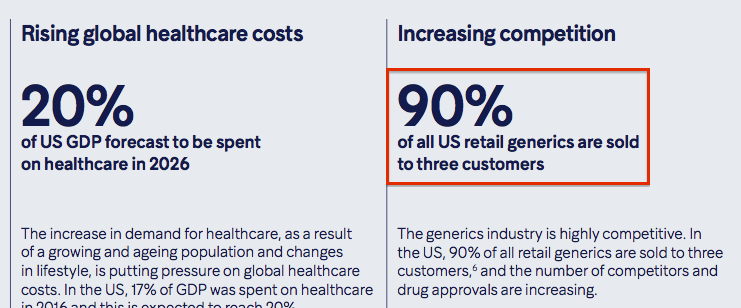

A concentrated customer base is unlikely to help matters. Hikma’s annual report admits 90% of Generics revenue in the US — representing 29% of total sales — is sold to just three wholesalers:

Underlining the sector competition, this 2019 industry study from the Association for Accessible Medicines claims the pricing of generic treatments in the States declined during 36 out of the 38 months leading up to September last year.

Progress at the acquired West-Ward Columbus was also hampered by “slower approvals for certain new products”. Similar to the patented originals, generic treatments must also receive regulatory clearance — and the delays can become protracted.

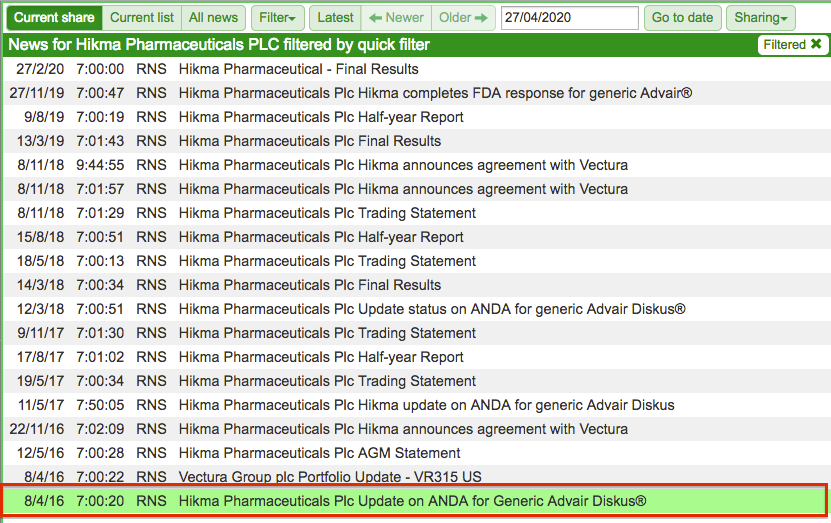

Hikma’s development of a generic version of Advair Diskus — an asthma treatment sold by GlaxoSmithKline — is a good example of how long the process can become.

Hikma first mentioned Advair Diskus back in 2016 when the generic product was initially submitted for regulatory approval:

Four years on, the treatment has yet to receive US approval following a dispute over whether an additional clinical study was required. Hikma eventually conducted the extra study and currently expects the product will receive approval later this year.

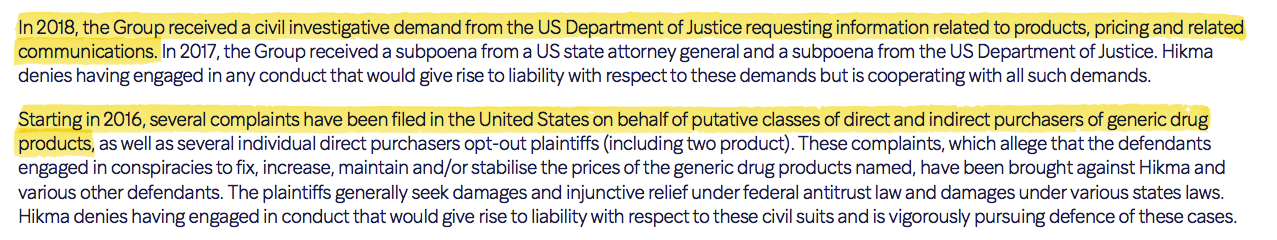

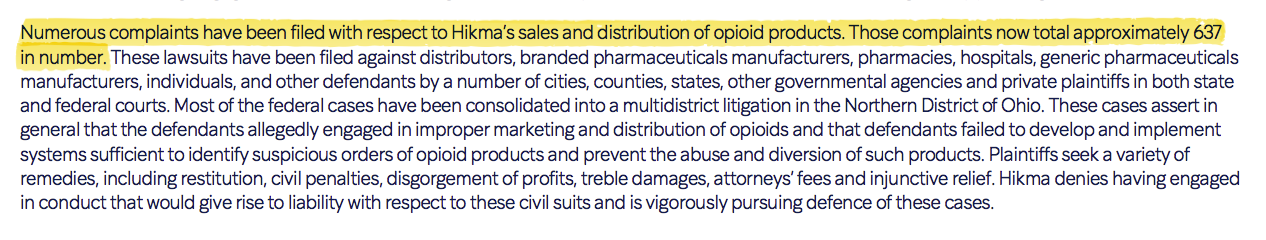

Selling pharmaceuticals in the States also comes with legal issues. The annual report fine-print lists a Department of Justice investigation into price fixing and 637 complaints about Hikma’s sales of opioid products:

Hikma Pharmaceuticals’ SharePad Summary

The SharePad Summary for Hikma is shown below:

Important observations include:

- The positive growth forecasts for the current year (second row);

- The presence of debt and a pension deficit (third row)

- The modest cash conversion (third row), and;

- The attractive margin and respectable ROE (fifth row).

Let’s start with the debt and pension.

Debt and pension deficit

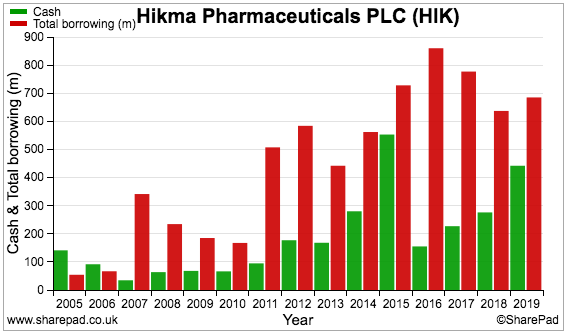

Hikma has operated with more debt (red bars) than cash (green bars) since 2007:

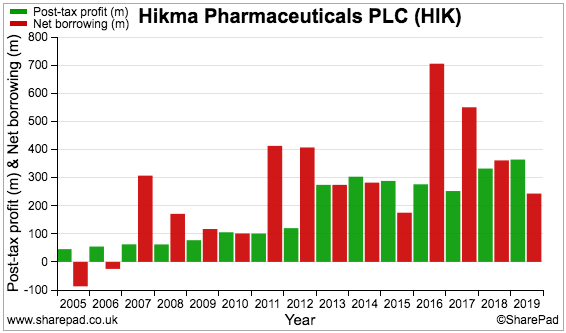

The borrowings do not seem too onerous compared to the cash position and recent profit. On the chart below, earnings (green bars) last year exceeded net debt (red bars) for the first time since 2015:

Hikma can easily afford the interest on the debt. During 2019, pre-exceptional finance costs of $35 million were covered an adequate 14 times by the $508 million pre-exceptional operating profit.

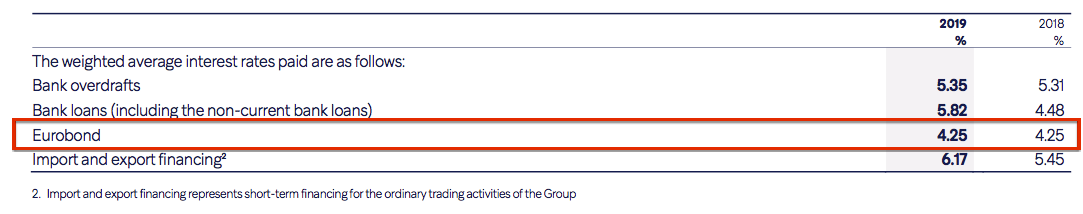

The annual report reveals the bulk of Hikma’s borrowings are represented by a Eurobond that carries a 4.25% rate — a level that does not suggest the lenders are particularly worried about a default:

For some perspective, GlaxoSmithKline claims to have an overall interest cost of 3.8%.

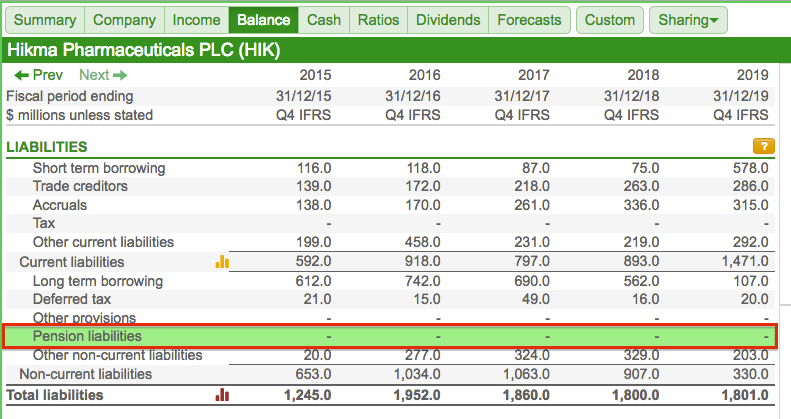

Top marks for SharePad for spotting Hikma’s pension liabilities.

Although the main Balance tab shows Pension obligations of zero…

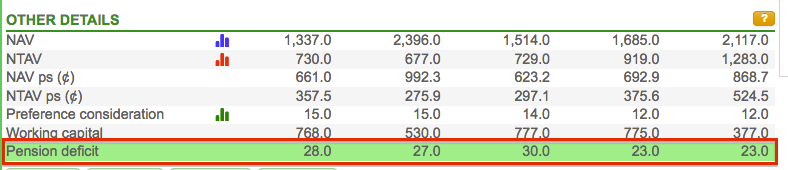

…pension liabilities of $23 million are recorded under Other Details:

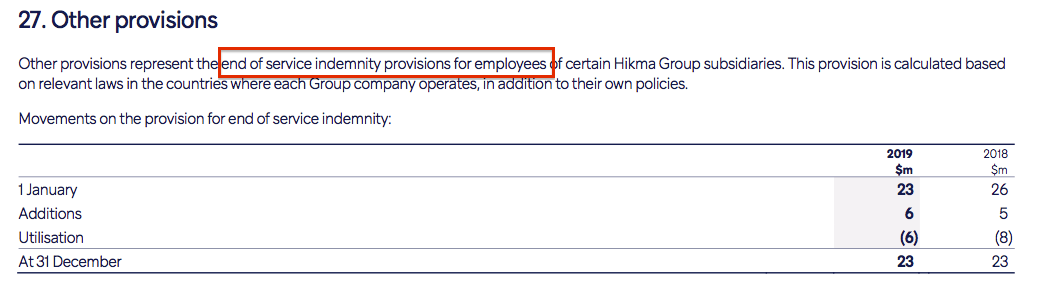

Why the discrepancy? Hikma accounts for its pension scheme — or what it calls “end of service indemnity provisions” — within “other provisions”:

The $23 million obligation is not obviously concerning given pre-exceptional operating profit topped $500 million last year.

Cash conversion and working capital

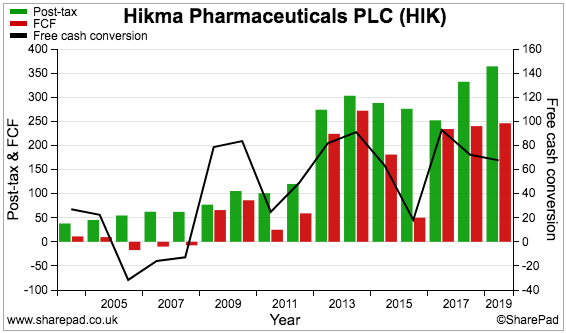

Hikma’s cash-conversion percentage (black line, right axis) has been very inconsistent:

My Renishaw write-up explained how cash conversion is often held back by:

1) Additional working capital absorbing significant amounts of cash, and/or;

2) Expenditure on tangible and intangible assets substantially exceeding the associated depreciation and amortisation charged against profit.

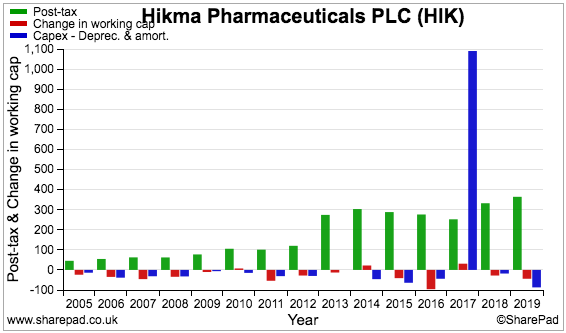

The following chart compares Hikma’s earnings (green bars) to additional investment in working capital (red bars) and the ‘excess’ capital expenditure (blue bars):

The chart is unfortunately distorted by the aforementioned $920 million write-off.

I nonetheless double-checked the accounts and determined that capital expenditure — both tangible and intangible — is adequately reflected by the associated depreciation and amortisation charges.

However, Hikma’s working capital does require further comment.

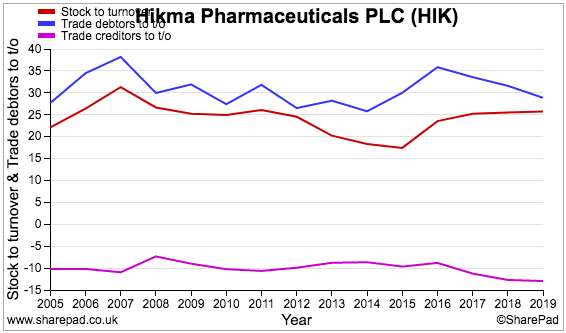

This next chart compares the levels of stocks, trade debtors (amounts owed by customers) and trade creditors (amounts owed to suppliers) to revenue:

Stock (red line) at 25% implies a lot of product sits in Hikma’s warehouses.

Meanwhile, trade debtors (blue line) at 30% of revenue suggests customers are not always that timely settling their bills.

The power of SharePad allows us to put those working-capital ratios into greater perspective.

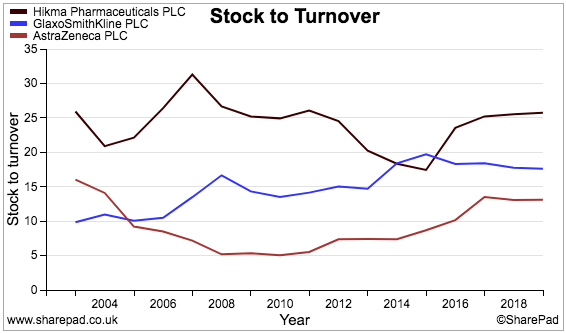

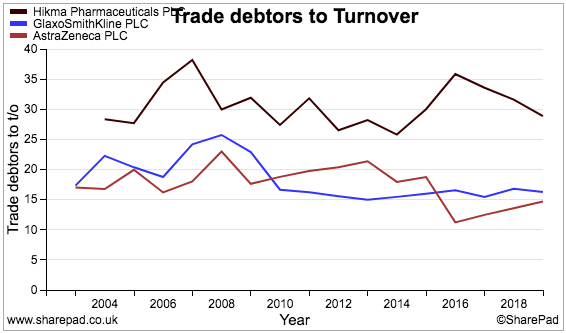

This chart compares Hikma’s stock-to-revenue ratio (black line) to those of sector giants GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca:

And this chart compares Hikma’s trade-debtors-to-revenue ratio (black line) to the same two shares:

Hikma clearly operates with relatively more cash tied up in stock and unpaid invoices than its larger rivals.

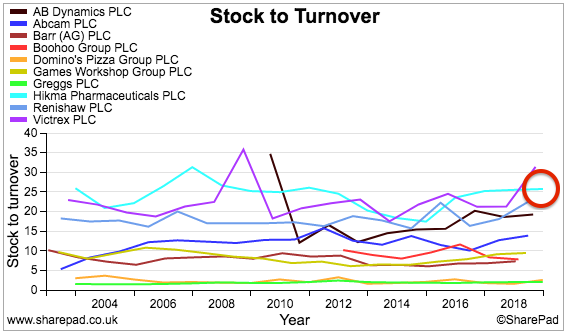

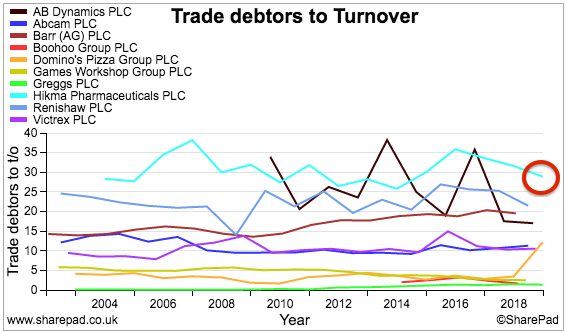

In fact, a comparison of Hikma against nine other shares I have reviewed for SharePad does not show Hikma in a great light (light blue lines, red circles):

The ideal situation of course is to carry as little stock and possess as few trade debtors as possible — that way, the risk of stock becoming outdated and bills going unpaid is lower.

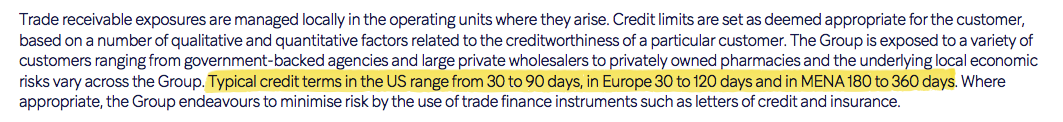

Hikma’s annual report explains some of the company’s working-capital arrangements:

Customers in the Middle East and North Africa are given credit terms of between 180 and 360 days!

Margin, ROE and R&D

Hikma’s group margin has been hampered by the ups and downs of the Generics division:

I estimate the average margin since flotation to be approximately 17%, which is very respectable level of profitability.

I should add that, before central costs, the Injectables division typically boasts a margin of at least 35% while the Branded division typically boasts a margin of 20%. Two-thirds of total revenue may therefore enjoy a more predictable ‘moat’.

Some care needs to be taken with Hikma’s ROE figures:

Although the accounts no longer carry the assets that were written off, that $920 million charge cannot really be ignored within the ROE calculation. (The $920 million was money spent that ultimately gave a return of zero!)

The $920 million write-off plus a bevy of other earnings adjustments since the flotation come to approximately $1.3 billion.

Add that $1.3 billion back on to the $1.9 billion equity denominator takes the 19% ROE reported for 2019 down to more average 11%.

I suppose whether Hikma’s future returns will mirror that 11% depends upon the group making any further duff acquisitions.

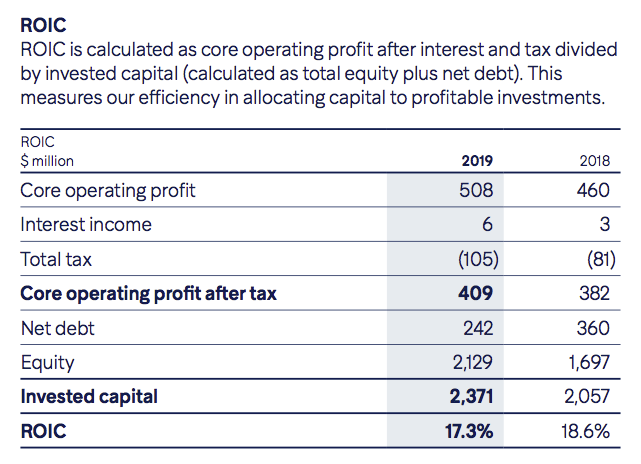

Hikma includes return on invested capital (a slight variation of ROE) as a key performance indicator, which is a good sign — but again the denominator does not adjust for the West-Ward Columbus write-off:

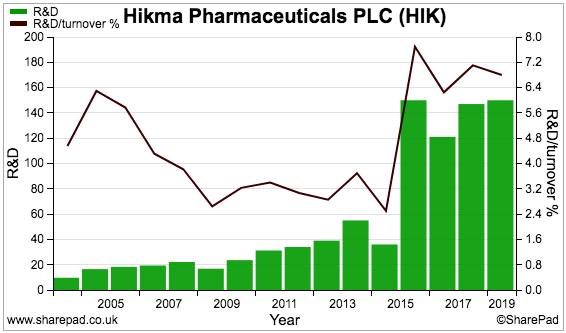

SharePad shows research and development as a proportion of revenue having increased to 7%:

For comparison, SharePad reveals the same ratio for GlaxoSmithKline to be 14% and AstraZeneca to be 24%.

Latest results, forecasts and valuation

Hikma’s 2019 results seemed quite reasonable.

Revenue gained 6%, profit improved 10% and the dividend was lifted 16%. Note that the figures were released during late February — before the outbreak of Covid-19 in the UK and the US.

The outlook for 2020 seemed positive at the time. Injectables revenue ought to grow by around 7.5%, Branded revenue ought to increase by about 5% and Generics revenue ought to remain flat.

City analysts then translated those projections into the following forecasts for the next few years:

Whether those estimates eventually prove accurate is anyone’s guess at present. However, Hikma appears confident. Two weeks ago the firm’s AGM update claimed:

“Hikma has made a strong start to the year despite the challenging market conditions that have arisen as a result of COVID-19. This is a complex situation which we are continually monitoring, but we have confidence in the outlook for the Group and we are pleased to reiterate our full year guidance for 2020.”

Hikma’s trailing P/E does not seem too extreme at present, although the rating has never been truly stratospheric:

Perhaps the market has always been wary of Hikma’s acquisitive nature.

I suppose a ‘buy’ case would be somewhat easier to make if the acquisitions were toned down, working-capital levels were improved and the more attractive Injectables and Branded divisions could grow to become an even larger part of the group.

Mind you, current Hikma shareholders will not be complaining too much given how the shares have outperformed this year.

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Disclosure: Maynard does not own shares in Hikma Pharmaceuticals.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.