In his quest for companies that control their own destinies, Richard discovers luxury fashion brand Burberry, a company whose products he is in no danger of buying.

Last time, I promised to investigate one of the shares I found while filtering for vertically integrated companies, companies that control their own destinies because they control many of the activities required to supply a particular product or service.

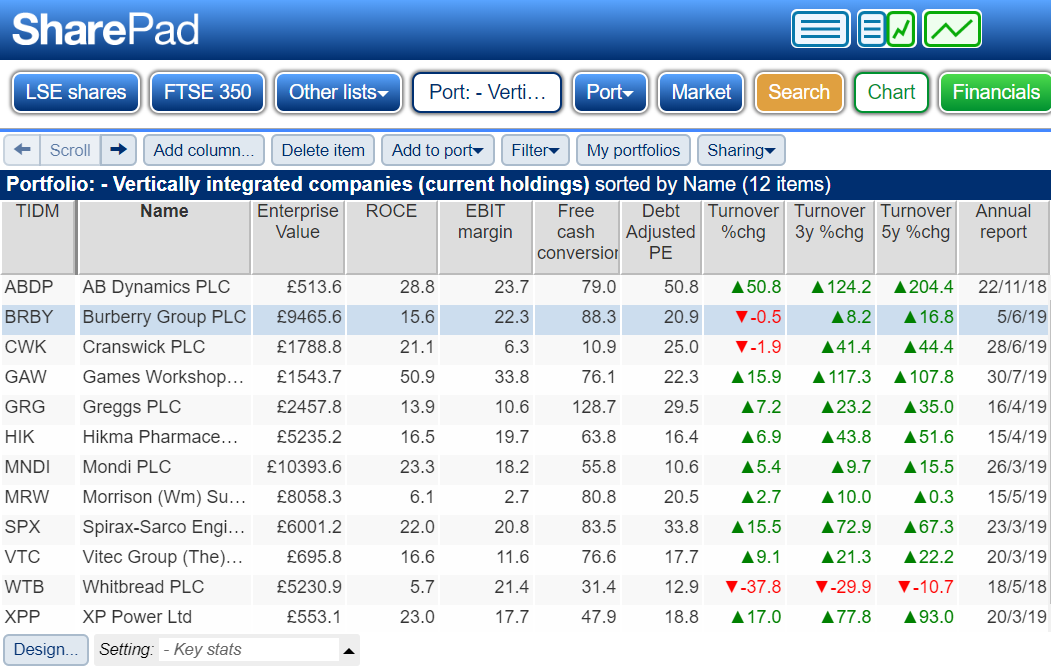

A portfolio of vertically integrated companies

The filter dredged up only a few* names, probably because the phrase I used to trawl SharePad’s news feed was “vertical integration” (and variants of it), which is jargon. Not all companies that supply their own operations, or sell their own products to the ultimate user, for example, use the term.

The results may have been lacking in quantity, but they were not lacking in quality. Put these twelve companies into a portfolio, then page through their share price charts using the spacebar and you will see they have almost without exception been good long-term investments. Maybe that is a coincidence, maybe it is not.

The financial metrics in the table columns should help to find good quality businesses. That is to say businesses that are growing profitably. Enterprise Value, Return On Capital Employed, EBIT margin, Free cash conversion and the Debt Adjusted Price-Earnings ratio in the table above are all lease adjusted and based on the most recent (TTM – Trailing Twelve Months) results, by the way. SharePad puts this information in the column headings, but I have edited them to make them more readable. Perhaps it is also no coincidence that most of the companies talking about vertical integration appear to be growing profitably.

In deciding which companies to investigate first, I could have sorted on the Debt adjusted Price-Earnings ratio and started my investigations with the share trading at the lowest valuation, which is Mondi. I could also have started with the most profitable by sorting on Return on Capital Employed, in which case Games Workshop would have been first on the list.

Being a simple soul I sorted alphabetically and started with AB Dynamics, which makes testing equipment for cars, principally robots. The company is experiencing explosive growth and trades on an a Debt Adjusted PE of 50.

Though AB Dynamics may be an exception that proves the rule, companies trading at such high valuations rarely justify them and I lack the foresight required to weed out the few that will keep growing rapidly, from the many that will not. AB Dynamics is an interesting business but at the current price, I am not in a hurry to investigate. Instead, I picked Burberry, a luxury fashion brand that is trying to kindle more rapid growth. Its debt adjusted PE is also high, but not unthinkable, at 21, equivalent to an earnings yield of 5%. Theoretically that promises a 5% return on our investment if the company sustains its current level of profit, and more if it grows.

Vertical integration at Burberry

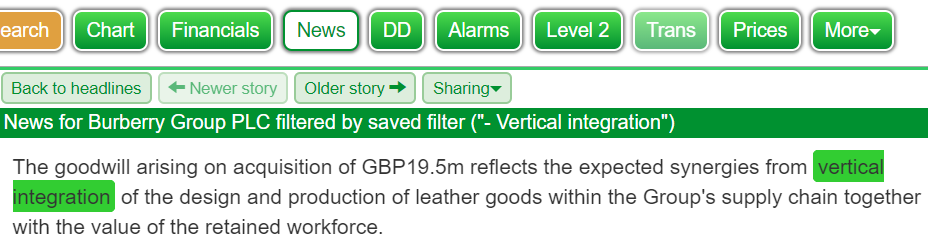

SharePad found a mention of vertical integration deep in Burberry’s preliminary results announcement of May this year. Buried in Note 23, are the details of the acquisition of Burberry Manifattura in September 2018, and buried in those details is the following sentence:

It means Burberry paid £19.5m more for a business than the value of the tangible assets, the buildings, equipment and so on, that it had bought. This amount is recorded as an intangible asset on the balance sheet, goodwill, but what exactly does Burberry think it bought? The announcement explains the acquisition will make Burberry more efficient through vertical integration, so in part it reflects the value of those efficiencies. It also reflects the value to Burberry of an expert workforce, which designs and manufactures leather handbags and other accessories.

The annual report tells us more. Burberry Manifattura employs 100 craftswomen and men, and the acquisition gives Burberry more control over quality, cost, delivery and sustainability of its leather goods. It was a division of a longstanding supplier, and now it is Burberry’s “centre of excellence” for leather goods. According to chief executive Marco Gobbetti, the acquisition and elevation of Burberry Manifattura is: “a major milestone… and a statement of our ambition in this strategically important category.”

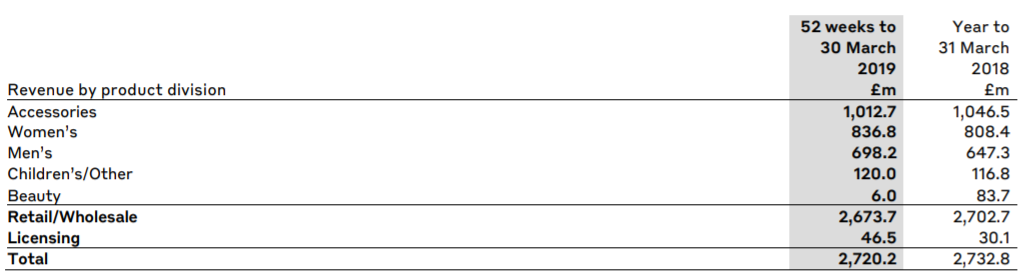

How important is this ‘category’? Note 3 to the accounts shows Accessories earned Burberry over £1bn in revenue in 2019, about 37% of total revenue:

Even when Burberry uses suppliers like Johnstons of Elgin, which supplies Burberry with cashmere, it relinquishes control only reluctantly. Johnstons recently achieved accreditation for self-inspection, a process that required more than a year of training, testing, and the development of audit processes.

Burberry seeks a high level of control because its products truly are expensive. There isn’t a bag on Burberry’s website for less than £500, and the famous trench coats cost upwards of £1,290. Search the Internet for Burberry’s most expensive product and the claims tend to top out at £22,000. I am not going to try and get into the mindset of somebody who would pay that much for a look, or explain the economics of goods that get more desirable the more expensive they are, because these things are alien to me. But judging by Burberry’s annual report, the company recognises that when you are charging people so much, pretty much everything about the product must be perfect, design, quality, sustainability, marketing and customer service for example. To achieve that Burberry needs control, which it exerts in part through vertical integration. That gives it a hand in almost every activity in the chain that takes a hide or the hair of a goat and puts a handbag or cashmere sweater into the hand of a very rich person. Burberry:

- Operates its own design HQ in London

- Manufactures at fully owned facilities in the UK and Italy

- Operates 431 stores (including concessions and outlets) and its own website serving 44 countries.

And before you say it does not farm, it trains farmers in developing countries to help them meet its quality and environmental goals.

Burberry’s goal is to become even more luxurious because it believes that all the money in fashion these days is going to the bottom end of the market and the top end. It does not want to be selling ‘premium’ apparel and accessories when even its customers are willing to mix and match, adding a touch of Burberry to an otherwise cheap and undistinguished (brand-wise at least) wardrobe.

On Louis Vuitton’s website, you won’t find a handbag for less than £1,000, and its website claims “The Louis Vuitton leather goods collections are exclusively produced in our workshops located in France, Spain and the United States.”

You may well question why, if other luxury fashion brands also manufacture and sell their goods, what advantage Burberry gets from vertical integration. I wonder if it needs an advantage over other luxury brands – there are not that many of them. According to Gobbetti, only 20 luxury fashion companies earned 97% of the industry’s profit in 2019. Perhaps all the incumbents need to do is stop new entrants breaking through. The cost of near perfection in the form of vertical integration might be a prohibitive barrier. Once you’re in this rarified fashion zone, the normal rules of economics no longer apply.

Future of Fashion

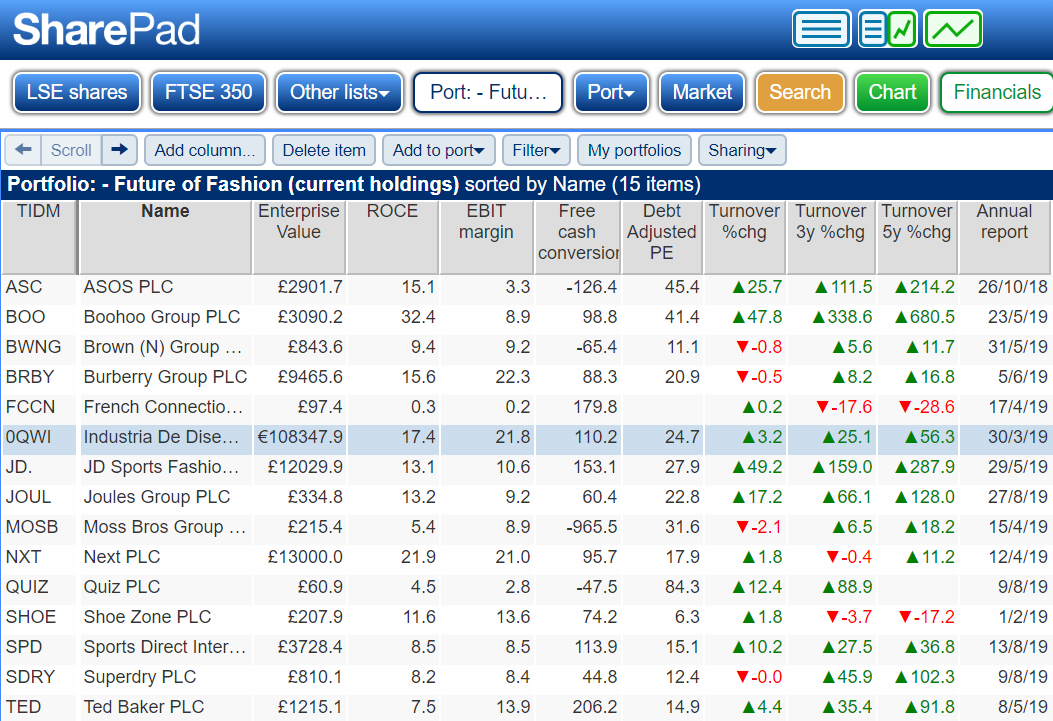

Burberry is a fashion brand, but as well as designing, it manufactures and retails, which is why I have added it to my Future of Retail portfolio, and since the portfolio was focused on fashion retailers, I have renamed it the Future of Fashion.

At a reader’s instigation, I have also added Industria De Diseno Textil with its even odder identifier 0QWI. It is a fashion empire listed in Spain and probably known to you through its store chain Zara, or perhaps Inditex, as the parent company is commonly known.

I can see why my correspondent thought it worthy of inclusion. With an enterprise value of nearly 110bn euros, Inditex is an order of magnitude bigger than the biggest listed British fashion companies, JD Sports Fashion (enterprise value £12bn) and Next (enterprise value £13bn). In terms of profitability and free cash conversion it is right up there with class-leader Next.

Richard Beddard.

*My portfolio of vertically integrated companies includes more companies because I have added some I already know to be vertically integrated, even if they do not shout about it. They are: Churchill China, Dart, Dewhurst, FW Thorpe, Goodwin, Victrex, Renishaw, and Tristel.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.