Richard likes a business that is in control of its own destiny. He takes a look at DFS plc, the sofa seller that unexpectedly featured in his list of vertically integrated businesses.

Of all the names that came up in my trawl for vertically integrated businesses, sofa seller DFS was perhaps the most surprising.

To recap, a vertically integrated business carries out, or is heavily involved in, many of the activities required to bring a product to market.

Vertical integration gives companies more control of their product and how it is sold, but there is a cost in terms of the capital required to fund so many capabilities and the complexity of the business.

I believe the companies most suited to vertical integration are the strongest: firms with very sound finances that perform well through thick and thin. These businesses can afford to be vertically integrated, and in turn vertical integration gives them many ways to develop distinctive capabilities.

DFS’ vertical integration is surprising because it sells furniture, like a lot of companies. I could not tell you why we bought the sofa in our kitchen from DFS instead of its listed rival SCS for example, or indeed John Lewis like one of the sofas in our lounge.

In fact, I had forgotten the kitchen sofa came from DFS until my wife reminded me when I told her what I was writing about (she says it is because she liked it, and the man in the shop was nice).

DFS claims to sell a third of all sofas in the UK, three times more than its nearest rival. It says that its name is searched online more times even than the word ‘sofa’.

Growth opportunities include its expanding Sofology brand, European showrooms (it has a presence in Spain and the Netherlands), and beds and homewares, which are newish product categories.

Perhaps it is doing something special.

Vertical integration, DFS style

The newly published annual report mentions vertical integration only once in a list of competitive advantages it believes will serve it well:

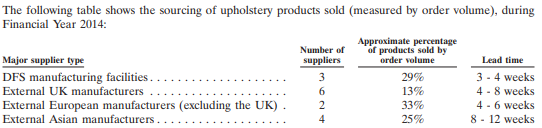

To learn more about the business, we can reach for the IPO prospectus because, after a period under private ownership, DFS relisted in 2015 and the more detailed information provided about the business model is probably still current.

The prospectus claims DFS has “end-to-end” direct control of customer service, which means it not only operates the stores but performs quality checks, delivers, and installs the furniture in its own purpose-built vehicles, and provides after-sales service through directly employed upholsterers.

The company believed this service culture coupled with a ten-year frame guarantee (now 15) had improved its standing in customers’ eyes substantially, as measured by its Net Promoter Score, a measure of customer satisfaction.

It also reported a peer-group leading TrustPilot rating of 8.8 out of 10, which has improved (I presume, the denominator has changed) to 4.7 out of 5.

Before we pop the Champagne corks though, in terms of customer perspectives competitors may have upped their games too. SCS offers a longer 20-year guarantee, and its TrustPilot rating is the same (4.7).

Furniture Village, scores a lowly 3.3, though.

The other specialist furniture sellers in the peer group no longer exist independently. Sofology was acquired by DFS in 2017, having changed its name from Sofaworks. Curiously it was a legal challenge from DFS that forced the name change (DFS owned the Sofa Workshop brand).

Loss-making Harveys Furniture went into administration in 2020, apparently outcompeted and done in by the pandemic.

Recent history suggests DFS is a formidable competitor, and there is another aspect to its vertical integration: It is a manufacturer.

One aspect of buying sofas I do remember is months sitting on dining chairs, poufs and ad-hoc benches waiting for the bloomin’ things to be delivered. This is because furniture shops do not generally hold stock, except what they have in the showrooms.

In 2014, DFS had two dedicated frame factories and nearby design studios. These, it said, gave it an advantage in terms of lead times, as well as control of costs and quality and insights to help it manage external suppliers.

Can DFS profit through thick and thin?

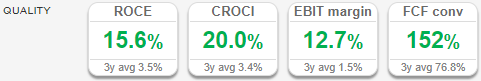

At first glance, the basic statistics in SharePad confirm that it is a high quality business:

In the year to June 2021, DFS earned decent profit margins, high a high return on capital both in terms of profit and cash flow.

The three-year averages (in grey) tell a different story, because in 2020 DFS performed poorly. The results this year and last have been skewed by the pandemic, which makes judging the company’s short history on the stock market somewhat treacherous.

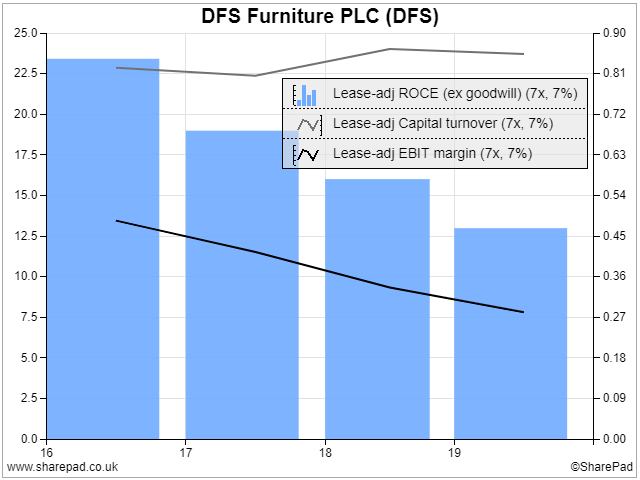

Before the pandemic, DFS’ profit margins and return on capital were healthy, but on a downward trend:

Like many other retailers and manufacturers, DFS had to shut down its showrooms and reconfigure its factories, warehouses and showrooms due to the pandemic, so it is hardly surprising profitability suffered in 2020.

But it has also experienced a surge in demand, as people sitting at home on tatty upholstery have redirected money they could not spend on travel and going out into their homes. This explains its excellent performance in 2021.

But the pandemic is unusual. In a recession, we would normally expect demand to slump because money is tight and sofas are expensive.

It is amazing how we can come to cherish the body-conforming contours of a much-loved old sofa if we cannot afford to buy a new one. We can put off buying sofas for years (trust me, I am expert at dragging my feet in this regard).

Since DFS was in private hands during the Great Financial Crisis, it has been a long time since we have seen how it performs during a “normal” recession.

I owned shares in SCS when it went into administration in 2008, though. It takes the prize as my biggest loss in percentage terms (100%), and probably in cash terms.

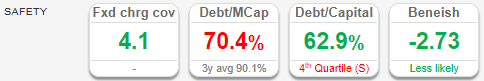

SCS had no bank debt, but lots of rented showrooms. Back then companies were not required to recognise their rental obligations as a kind of debt, but they are now and rental obligations are included in SharePad’s debt figures.

DFS has a high debt to capital ratio because of its combination of bank debt and lease obligations, which makes me wary. The debt is funding the high fixed costs of showrooms, warehouses and factories, which might not be recoverable if we stop buying sofas.

SCS went bust because it could not afford to pay the rent. The convoluted sequence of events that led to this unhappy outcome is a story for another day but I learned these lessons in 2008:

- To adjust debt to include lease obligations in my analysis

- Be wary of companies selling so-called “big ticket” items

- Not to take pictures of myself looking smug about investments, while seated on sofas*

Here I am in SCS posing as a potential customer, but actually checking out my investment in the company, in 2008.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the salesman was desperate to sell me a sofa. He agreed to take my picture sitting on one so I could show my wife. Months later my investment was worth nothing.

While vertical integration gives companies more control of their own destinies, and I am keen on that, swings in demand remain outside DFS’ control and I expect they probably will remain significant factors in its long-term performance.

DFS probably contravenes my requirement that a vertically integrated business be capable of performing well through thick and thin.

* To be clear, I am looking smug about the boots in the first photo, and I do not own shares in DFS.

Richard Beddard

For more information about Richard’s scoring and ranking system (the Decision Engine) and the Share Sleuth portfolio powered by this research, please read the FAQ.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Who makes the boots!?

Ha! I wasn’t expecting that question. They’re made by Vivo. Perhaps an acquired taste. Grippy sole but no cushioning for a ‘barefoot’ experience. I love ’em.

Nice article Richard. You look a whole lot healthier now than you did back in 2008. Perhaps personal health is linked to the health of your investments?

On the SCS front it looks like a decently run business now but perhaps it only looks cheap because of the post-pandemic bounce. After all how often do people replace a sofa? We’ve had ours twenty years and they’re still in good shape.

Thanks Damian (I think!)

We bought a new sofa a couple of years ago. The one it was supposed to replace was 30 years old. It predated all our children who bounced on it for their entire childhoods. When it came to getting rid of it we couldn’t do it. Even once they are worn and sagging they have sentimental value!

One of the things I wonder about DFS is its move into other homewares. May be an attempt to offset the cyclicality sofas as well as find new avenues for growth.

Not only has ScS got no debt, it has so much cash it could return £50m (half its cap) without breaking step.

That would leave £37m net cash (ex lease obligations) which is the level of customer deposits.

I hold.

Hi Richard, very entertaining, thanks.

“I owned shares in SCS when it went into administration in 2008, though. It takes the prize as my biggest loss in percentage terms (100%), and probably in cash terms.”

I think SCS may be one of your best investments given the lessons learned, and I agree that the combination of high fixed costs and customers who can put off buying your product for years is not fantastic.

I don’t know anything about DFS beyond the fact that it sells sofas, but it would have to have something pretty special up its sleeves to offset that risk.

John

Thanks John!