Richard uses SharePad and Artificial Intelligence to help him learn about listed law firms. The legal sector is not quite the unappreciated stock market backwater he anticipated. It is a bit of a horror show, with a couple of light intermissions.

It was the data that alerted me to the opportunity in listed law firms. My last article highlighted Gateley, a share that scored 0 strikes according to my 5 strikes system (described at the end of this article)*:

How the law firms scored

| Name | Previous Annual Report | Dir holdings % | Float date | Strikes | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gateley | 25/9/23 | 1.79 | 8/6/2015 | 0 | |

| Keystone Law | 15/5/23 | 29.5 | 27/11/2017 | – Float date | 1 |

| Knights Group | 21/8/23 | 22.5 | 29/6/2018 | – Float date – Acquisitions – CROCI – Debt – Share count |

X |

| RBG | 27/4/23 | 20.5 | 8/5/2018 | – Float date – Acquisitions – CROCI – Debt – ROCE – Share count |

X |

In the table, each strike is a potential cause for concern, so no strikes is good.

Keystone Law scores well too, receiving one strike because it floated in 2017, more recently than 2015. This arbitrary benchmark penalises companies with short stock market histories because we have less data about them. It might be tricky or not possible to work out how they have performed through thick and thin.

Gateley, the first UK law firm to abandon its partnership structure and list on the stock market, squeaked through without a strike because it floated in 2015.

My initial research does not reveal anything major that differentiates Gateley from other large law firms to explain its strong financial performance. Perhaps it is just managed well.

Founded in 2002, Keystone Law may be something different. It enables self-employed lawyers who work from home or their own offices to serve mostly small businesses. A homegrown IT system gives the lawyers administrative support from the mothership and, for a commission, allows them to pass work onto other Keystone lawyers.

I do not know if Keystone’s networked business model is unique, but it is among listed law firms and, as we shall see recently delisted law firms. The company says it is more efficient and entrepreneurial than traditional lawyers in offices.

Encouragingly, David Knight, the entrepreneur who co-founded Keystone, is still heavily invested. He owns 29% of the shares.

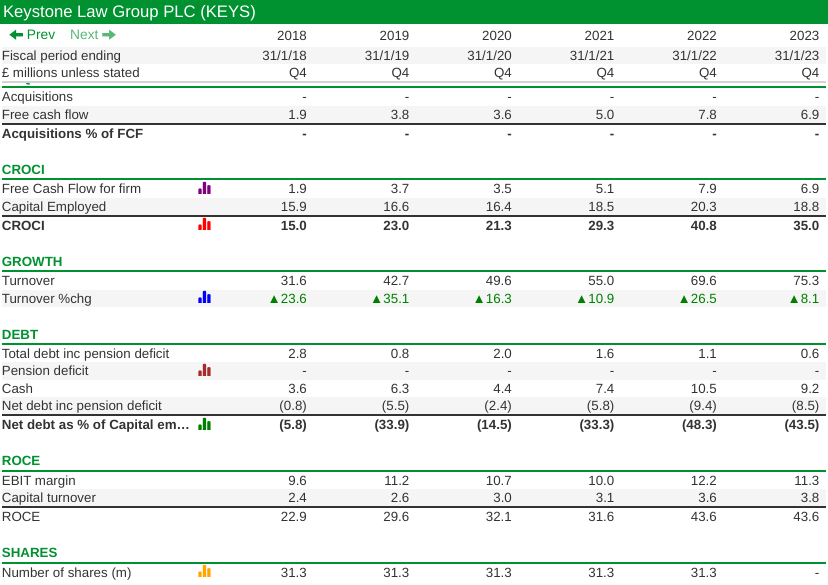

Although both Gateley and Keystone have performed well as businesses, and unlike the others entirely under their own steam, Keystone has been the standout law firm since it listed in 2017:

Source: SharePad custom table. See below* for more detail

It also had net cash at the end of each of its financial years.

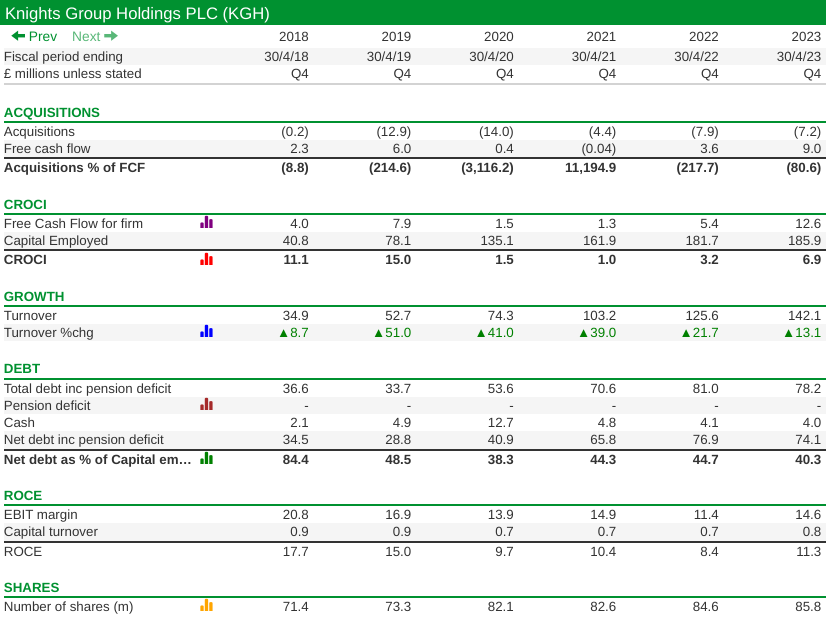

The performance of the others has been a lot less auspicious. Here is the same data for Knights, the best of the worst judging by the numbers (RBG, the only “X” in my table has yet to publish its results for 2023):

Knights has grown revenue even more rapidly than Keystone Law, but it has bought growth. It has borrowed and raised money from investors and spent it on acquisitions. Unlike Keystone’s cash pile, it has significant financial obligations and the returns have not been impressive.

This, it turns out, is a familiar story, but before we look at what may have gone wrong at some of these firms, a brief diversion.

Experiments in AI, part 2

AI makes things up. An AI hallucinated me a great CV. It is not to be trusted, but it can be useful in certain situations.

One of those situations is when we know next to nothing about a subject but want to get a headstart. The AIs know more than we do, but like an unreliable friend, we do not know which bits of what it tells us are true, and which are made up.

AI is also useful when we have a lot of information to synthesise. It would take me a week or more to rummage through five corporate websites, read five annual reports, and follow wherever those take me to get a satisfactory understanding.

An AI can do it instantaneously, and though the result is not as satisfactory, with a bit of fact-checking it can be good enough to make two critical decisions in the research process: Whether the subject interests us at all, and what might be the best next step (perhaps in this case, which is the most promising company to research).

You can rest assured, the last section of this article is not written by an AI and although some of the information in it came from Bing queries, it has been verified.

Learning from failed law firms.

The first problem we face when investigating a new sector is finding out which companies sit within it.

I turned to Bing, Microsoft’s ChatGPT-infused AI, to make my list of law firms, and cross-checked it in SharePad. Bing proposed six firms while admitting the list might not be exhaustive. The fact check revealed two of the six delisted earlier this year.

We can learn a thing or two about the risk of investing in law firms by examining what happened to those two companies.

DWF, which says it is the UK’s biggest listed law firm, was taken over by Inflexion. a private equity firm last month. inflexion thinks it has bagged a differentiated business because it combines legal and business services. With 30 international offices DWF also has the most developed international business.

inflexion also saw a bargain: The opportunity to buy a big business cheaply. Although the private equity firm paid a substantial premium to the share price, the share price was languishing near pandemic lows when the deal was announced in the Summer.

I am not surprised. I scored DWF before it delisted, but struck it out with an “X”, indicating five or more strikes, and summarised it in similar terms to Knights. DWF listed in 2019 and spent more on acquisitions than it earned in cash flow in its short stock market history. It had borrowed heavily and issued lots of shares to fund this activity and the returns were unimpressive.

The desire to scale up rapidly, a strategy shared by Knights and RBG, unnerves me because it can be like an arms race, and a lot of money can be wasted.

DWF’s experience leads me to question whether law firms are enjoying their time on the stock market. Running law firms more like regular businesses can be unsettling for partners that previously answered only to themselves and their clients, and the stakes they parlayed into equity will have declined in value if their share prices have.

Ince, the other law firm to delist, went bust in January. It delisted before I had a chance to score it, but its financial position was obviously dire.

Law firms can be as badly run as any other business, but there may be additional risk. When law firms go wrong, teams of lawyers rush to join rivals, accelerating the collapse rather like a run on deposits can precipitate the collapse of a bank.

Ince was sold out of administration to Axiom, another law firm, and just read what was going on at Axiom Ince in October!

I started writing this article thinking I might have found a group of companies performing well that was underappreciated by the stock market.

But only two of them, the two that have made no acquisitions, have performed well as businesses, and they are appreciated somewhat. Gateley’s share price is up a very modest 40% on its 2015 IPO price and Keystone’s share price is 150% higher than it was when it floated in 2017.

RBG is 80% below its IPO price, and Knights 40% lower.

I think on a debt-adjusted PE of 10, Gately could be a candidate for a value-oriented portfolio, and on a debt-adjusted PE of 20, Keystone Law could be a candidate for a quality portfolio.

~

*Five Strikes

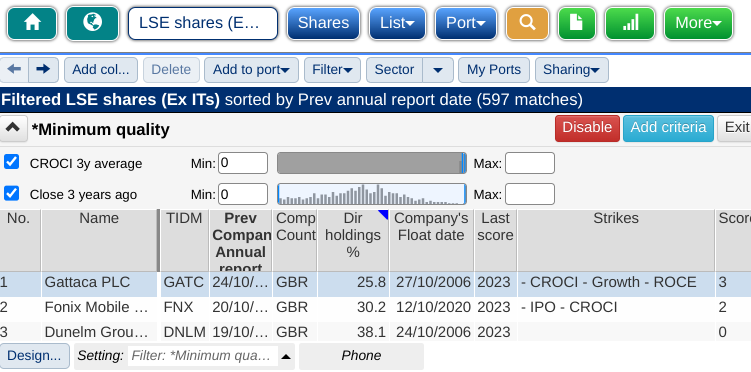

Five strikes is my main method of deciding which new shares to analyse. It uses a SharePad filter, A sharePad list view and a SharePad custom table to show me the numbers I need to make a preliminary evaluation.

I perform the same routine every working day when the stockmarket is open, although it could be once a week, or once a month. There would just be more shares to evaluate each time.

First I run a “Minimum quality” filter on SharePad’s list of LSE shares (excluding investment trusts). This filters out all companies that have been listed for less than three years or produced negative cash flows over the last three years. For these companies, there is very little data to go on.

The list view is sorted by the date of each company’s previous annual report, so I can easily see any that have been reported since I last checked the list. The next three columns show three data points that can potentially count against companies.

They are the company’s domicile (any company headquartered abroad gets a strike), directors’ holdings (if the directors do not have substantial shareholdings the share receives a strike), and the company’s float date (if the company floated after 2015 it receives a strike).

The first thing I note is the calendar year in a “last score” Note column so that I do not accidentally put a share through the process more than once a year.

Then I write down a code for each strike in the “Strikes” Note column, so I know what I didn’t like about the share. For example, Fonix Mobile floated in 2020, so it gets a strike “- IPO”. The other strikes in the screenshot relate to a custom table, which I display below the list view:

Although I can only fit five years of data in the width of this article, SharePad’s data goes back for decades if the company has been listed long enough, which means almost at a glance we can form an impression of how profitable and reliable a business has been.

Reliable growing businesses are often easier to analyse, and they can also be underrated because they tend not to be exciting, which is why they are my natural hunting ground.

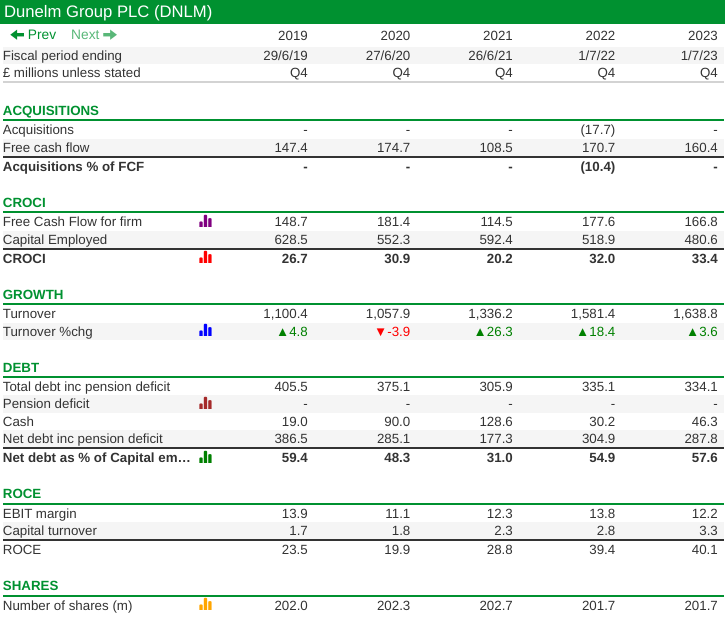

Dunelm is a good example, which is why it scores 0 strikes, a rare accolade.

The other two examples in the screenshot are not of the same calibre, but I would not rule them out as potential long-term investments.

Fonix Mobile earned negative Cash Return on Capital Invested (CROCI) in 2021, which, added to the strike for its recent flotation, gives it two strikes.

Gattaca scored three strikes for CROCI, Growth, and ROCE. The combination of negative cash flow in some years and low Return on Capital Employed is a bit of a turn-off, and it is unlikely, but not unthinkable, that I would investigate the company further.

Deciding whether a business has performed well or badly over the long term requires judgement. I did not penalise Dunelm’s negative growth in 2020, it was, after all, the first year of a pandemic, and anyway, I do not expect good companies to grow every single year.

If a company spends more than it earns on acquisitions in a single year, that may not be cause for concern. But if it spends many times more than it earns, or it spends more than it earns over a long period of time, it may be taking big risks.

Investors make judgements like this all the time, but I am trying to bring a bit more rigour to the process.

Finally, I total the number of strikes in the “Score” Note column.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Richard? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.