Richard takes a first look at Learning Technologies, a company aggressively buying businesses that make employee training and development content and software.

Learning Technologies’ is a slightly bewildering agglomeration of businesses that helps organisations get the best out of employees.

It creates training content for employers and makes software both for the creation of training content and for recruitment, performance management, and the development of employees.

Learning Technologies has bought and built numerous content creation and software businesses. Source: ltgplc.com/portfolio/

Understanding software companies is a priority in my own personal development, but the fact that Learning Technologies is increasingly pitching itself as a software company is not what drew me to it.

Another buy and build

The company traces its history back to 2013 when unlisted e-learning business EPIC took over a cash shell listed on the stock market.

The listing allowed EPIC, now called Learning Technologies, to raise money from investors to fund it’s new “buy and build” strategy.

Over the last eight years, it has acquired a gaggle of still independent providers of content and software that it could grow by selling the offerings of each subsidiary to the customers of the others.

The owners of EPIC before it came to market were Andrew Brode, Learning Technologies’ current chairman, who retains 20% of the shares, and Jonathan Satchell, who is Learning Technologies’ chief executive and currently owns 9% of the shares.

It was their long involvement in Learning Technologies, Mr Satchell was appointed in 2007 to turn EPIC around shortly before the two men acquired it, and their skin in the game, that nudged me to investigate the share, as well as Mr Brode’s reputation.

He is perhaps even better known as the chairman of RWS, a company that has grown tremendously over the last two decades, both as a result of doing more business and as a result of acquisitions.

RWS is a translation company and since translation is increasingly facilitated by software, and RWS provides machine translation software as a service, it would seem Mr Brode has transferable skills and valuable experience in terms of the businesses and their acquisitive growth strategies.

Mr Satchell has been involved in training since the 1980s.

Risky acquirer

When companies buy other companies with cash flow they have earned, we know the strategy is sustainable because it is self-funding and self-limiting. The freedom to make more acquisitions is constrained by the ability to make money out of previous ones.

When companies spend more than they earn on acquisitions they must borrow more, or issue more shares and sell them to investors, or pay shares to the owners of the companies they are acquiring.

Spending more than it earns means a company can grow faster, but when a new acquisition is big it can radically change the character of the combined entity. It can be difficult to appreciate how the company is changing, and it could be many years before we can form a view on whether the acquisition was a good one.

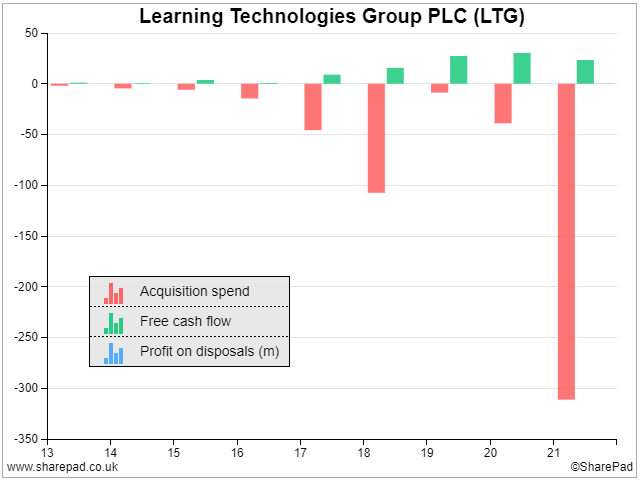

We can use SharePad’s financial charting facility to spot companies that spend more than they earn by comparing acquisition spend to free cash flow.

Free cash flow is money a company has left over after paying the bills relating to its operations and investment in equipment and product development. It can use this money to pay down debt, pay investors dividends, or acquire other businesses.

In the chart above, acquisition spend (the pink bars) is far greater than free cash flow (the green bars), and this discrepancy could be even greater if Learning Technologies has paid for some of its investments directly in shares.

Clearly, the company has not self-funded its growth, so it is the riskier kind of acquirer.

Risk, of course, works both ways. The risks might be paying off, but it is important to know what we are dealing with.

Are the risks paying off?

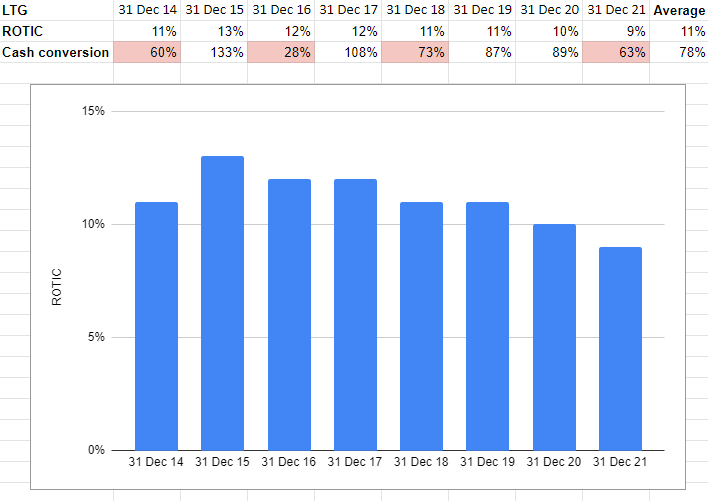

To establish whether the risks are paying off, I exported the statutory numbers from SharePad and adjusted them to calculate Return on Total Invested Capital (ROTIC), my goto ratio for assessing acquisitive companies.

This ratio compares the profit a company makes to the capital it employs including acquisitions at their original unamortised cost. It is perhaps the least generous profitability ratio and its purpose is to show whether the company has been a good acquirer.

Learning Technologies’ ROTIC. For a fuller description of this ratio, and a link to a worked example, please see this article. Source: SharePad and Learning Technologies’ annual reports.

Learning Technologies’ ROTIC is not bad. In every year except the most recent one, it has earned double-digit returns (after tax at the standard corporate tax rate).

The company’s profit figures used in the numerator of ROTIC (profit means the same thing as returns) are heavily adjusted though. The adjustments are mostly (to my mind) uncontroversial, although the exclusion of integration costs relating to acquisitions can be an opportunity for aggressive accountants to exaggerate the costs, and consequently exaggerate profit.

I have included cash conversion in my table as a quick and dirty way to test the accounting profit. Cash conversion compares adjusted profit and cash flow. There are good reasons why cash flow might be lower than profit when companies are investing heavily in equipment or software development for example, but generally speaking the bigger the divergence between the two, the more sceptical we should be.

I set an arbitrary level of 75%, below which I might be concerned, but I apply it to the average because for quite legitimate reasons cash flow varies markedly from year to year at many companies.

The table shows that cash flow has fallen below 75% in four of the eight years, but the average is 78% so Learning Technologies’ adjusted profit figure looks reasonably robust.

Neither am I too concerned about the dip in ROTIC to 9% in 2021. When a company buys another company it pays most or all of the consideration in one go but depending on when the transaction occurred, it may only have received returns from the company for a small part of the year.

To get around that I use the average of total invested capital in the current financial year and the prior year. That is of course a fudge. It kind of assumes that the company added to its capital evenly throughout the year.

Learning Technologies made four acquisitions during the year, but the biggest by a mile was GP Strategies, acquired on October 14, just a month and a half before the year-end.

The promise, and the peril

A low double-digit return on total invested capital may not be bad, but it is also not great. I do not think Learning Technologies is destroying value, but neither am I confident it is creating much.

ROTIC at RWS, Andrew Brode’s other business, is much higher, and so is the average ROTIC of many of the other businesses I follow closely.

There are other ways to judge acquisitions. Back in 2020, Maynard added up the revenue contribution of each new acquisition made by Learning Technologies in the year of acquisition.

This sum was roughly the same as the difference in revenue between the year of Learning Technologies’ first acquisition and revenue in 2019, its last full financial year.

In other words, he could not find much organic revenue growth.

As he said, and the chart at the beginning of this article shows, most of Learning Technologies’ spending on acquisitions has been recent, so they have not had much time to grow.

Their true potential may only be obvious once they have been integrated properly, so they may well generate higher revenues and higher profits in future.

That is the promise, and also the peril of buying highly acquisitive firms.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard