Richard re-examines one of his worst trades and considers whether changes at Portmeirion, the manufacturer of tableware and other home accessories, are enough to make him reconsider.

Half a failed trade

Portmeirion is one of the more severe of many blots on my trading history.

I added Portmeirion to the model portfolio I run for the investment platform interactive investor in early May 2017 when the shares cost 917.5p.

I removed them less than three and a half years later in September 2020 at a price of 376p.

The company paid dividends in the meantime, so my losses were reduced to 51% of my initial investment according to SharePad, after deductions for broker fees.

Since I mirror the model portfolio’s trades in my own Self Invested Personal Pension (SIPP), I lost money as well as face.

2020, when I lost faith, was the first year of the pandemic, and it would be easy to assume that I panicked along with the rest of the market.

That would not be true though. Portmeirion was one of only three holdings I liquidated in 2020 (out of nearly 30), and I added three new holdings that year.

There is a tendency to look at share price charts like this one, where we bought high, sold low and the price has subsequently gone up, and describe it as a failed trade.

In fact it is two trades. Adding the shares was a mistake because it did not go the distance and I lost money.

But since my time horizon is ten years, the decision to sell cannot yet be appraised. When it is, we would need to consider it against what I chose to do with the money raised from the sale, which, for the record, was rolled up into an investment in 4Imprint (previously appraised here).

The reason I rejected Portmeirion was that I had been losing confidence in the business for some time.

Diagnosis: diworseification

Back in 2016, Portmeirion was almost entirely a manufacturer of tableware. It owned Portmeirion Botanic Garden, a fantastically popular floral design collected by people around the world, notably in South Korea.

During the financial crisis, it bought two venerable but struggling British tableware brands, Spode and Royal Worcester, and revived them.

Its only other business, tiny in comparison, was Pimpernel, which makes accessories we put our tableware on or near: placemats, coasters and napkin rings for example.

Portmeirion was a relatively straightforward business. It had grown by extending the ranges of its popular designs and refreshing the designs occasionally.

This growth was augmented by developing new designs, often licensed from famous designers like Sophie Conran, and targeting new geographical markets.

New ranges, and new markets are risky though. They require investment and it does not always pay off, a process the company’s chairman once described to me as throwing clay at a wall and seeing what sticks.

Nothing had stuck as well as Portmeirion Botanic Garden, which in 2015 had earned the company £33 million of its £69 million revenue.

It first occurred to me that Portmeirion might be losing faith in this strategy when it acquired Wax Lyrical in 2017. Wax Lyrical is a manufacturer of home fragrances (candles, and reed diffusers).

Then I noticed that Portmeirion Botanic Garden sales were declining. In 2019, the company said the pattern earned more than £25 million in revenue, and in 2020 it reported a figure of more than £20 million.

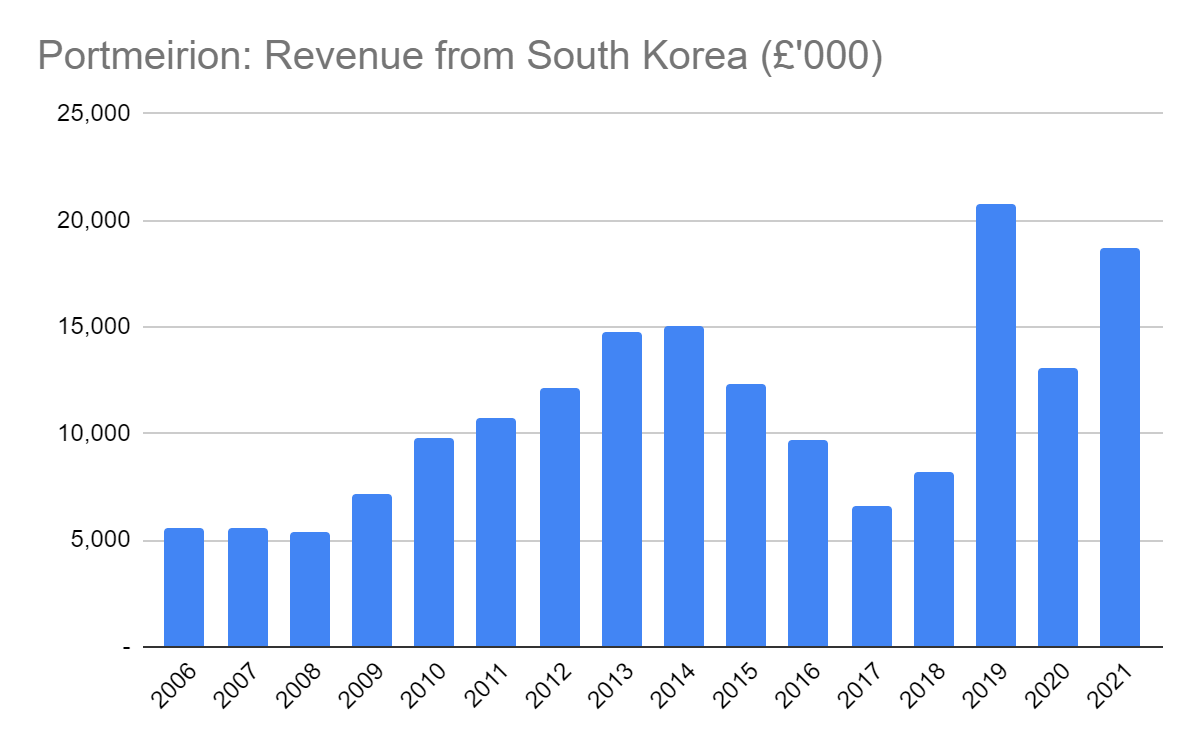

This decline in sales roughly coincided with erratic sales in South Korea, where Botanic Garden is popular. Portmeirion’s distributor there was losing market share to cheaper “grey” imports.

If the company was struggling to maintain sales of its most popular brands, and it was struggling to create new blockbuster brands, perhaps that explained why it was diversifying.

Then, in 2019 it bought Nambé, a US manufacturer of homeware, including non-ceramic tableware made from wood and metal.

I feared these were diworseifications.

Portmeirion’s segmental report indicated that the home fragrances business was making less profit than Wax Lyrical had as an independent business and in 2019, Nambé added very little profit, but debt to Portmeirion’s financial statements.

Then, with weakened finances as the pandemic broke, Portmeirion issued more shares to raise money, ensure its survival, and reshape itself.

With stores closed it wanted to invest money in its underdeveloped ecommerce sites and online fulfilment, which required new marketing and warehouse capabilities.

And having repurposed the Wax Lyrical production line to make hand sanitiser, it planned to build new hand and body care (soap) brands, a market it had not previously addressed.

I felt Portmeirion was throwing just about everything at the wall, and wondered whether anything would stick.

Prescription: Design direct

The company’s annual report for the year to December 2020 offered glimmers of hope though. Sales to South Korea fell 35%, but the company said its distributor had experienced a 15% increase in sales.

This did not translate into increased sales for Portmeirion because sales were still lower than the South Korean distributor had anticipated. It could supply from its own excessive stock and did not need much new product, a pattern that had disrupted the South Korean trade for some years.

Nevertheless, by designing exclusive products for the South Korean distributor, Portmeirion believed it was stabilising the market.

Furthermore, the company did not mention acquisitions, even as an aspiration, and it promised to increase the “vitality rate” of product development.

In putting the emphasis back on design, perhaps Portmeirion could recreate the stability of the years prior to 2017 and the acquisition of Wax Lyrical.

This year’s annual report, for the year to December 2021, reinforces and elaborates on that prospect.

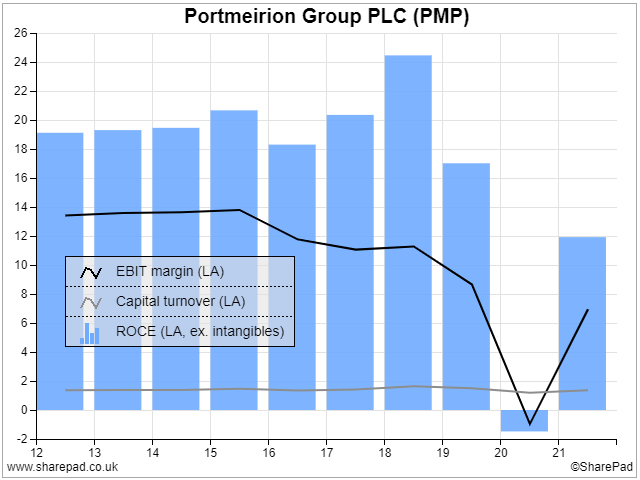

Turnover is at an all time high and, after flirting with losses in 2020, Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) has improved but is still some way below pre-pandemic levels.

Profit margins have been impacted by high freight costs and increased investment including factory automation, warehousing and a production line to produce soaps.

Strategically, the message is similar to last year. For now, at least, Portmeirion is all about making the most of its established brands through “timeless design”, which it hopes to sell more of outside its biggest three markets, much as it did before 2017.

The company is adding new products to Portmeirion Botanic Garden to commemorate its 50th anniversary this year, Spode Christmas Tree, a big seller in the USA, and its contemporary ranges.

The most novel aspect of Portmeirion’s new strategy though is online direct sales.

Portmeirion operates websites in the US and the UK, its biggest markets, and encouragingly it has adopted the proportion of direct sales as a percentage of total UK and US sales as a Key Performance Indicator. Currently it is 14.5%, up from very little before the pandemic.

By cutting out the middleman, direct sales are an opportunity to improve profit margins and develop closer relationships with end customers, who can be, in the case of the more popular tableware brands at least, enthusiasts.

Portmeirion intends to set up VIP clubs for its big brands, a policy used by chocolate seller Hotel Chocolat.

I am more sceptical about soaps. Portmeirion hopes to turn some of its tableware brands, Sarah Conran for Portmeirion and Royal Wrendale Designs, into soap brands.

It also plans to sell more home fragrance brands abroad, but it has been talking about exports since it acquired Wax Lyrical.

To my mind, the strategy gets less coherent the further from tableware it strays because designs make tableware unique in a way that I am not sure fragrances and packaging can differentiate candles or soap.

As for the big one, Botanic Garden, I looked in vain for a revenue number in this year’s annual report. Portmeirion says the pattern “still sells in significant volume around the world…”

Perhaps it is cynical to think Portmeirion’s failure to print a number means sales are still falling.

Indeed, if South Korean sales are anything to go by, Botanic Garden may be recovering too. Turnover from South Korea grew 43% in 2021 to 18% of total revenue and the company says there was “good sell-through to the end consumer” so the distributor may need more stock sooner rather than later.

Source: Portmeirion annual reports

To succeed, Portmeirion must be good at design and distribution. That appears to be its focus again.

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard