Richard warms the cockles of his heart in front of a digital fire, while reading his favourite investment book…

Christmas is approaching, and I must confess to a new and slightly eccentric guilty pleasure. In addition to mince pies and Irish Coffee, I have taken to working (from home of course) in front of an open fire, courtesy of Netflix.

The TV/fireplace actually makes me feel warm, and my mood is also lifted by the fact that as well as reading Bruce Packard, I am, for the first time in perhaps a decade, re-reading my favourite investment book.

I say my favourite investment book, but judging by how well two of my books have been thumbed it is a close call. Peter Lynch’s One Up on Wall Street is the book that really got me into investing. I came across Janet Lowe’s The Rediscovered Benjamin Graham a bit later, but there is something very special about it, hence the notes sticking out of the margins:

Back to basics

Graham literally wrote the book on value investing, two in fact: “The Intelligent Investor” and “Security Analysis”. Such is their influence that both have remained in print since their first editions and to put that in perspective, the first edition of Security Analysis was published nearly ninety years ago.

If I want to be taken seriously it is probably unwise to admit that I have not read either from cover to cover. They are long books, detailed, and sometimes deal with anachronistic topics. Security Analysis is the more scholarly, but neither could be described as entertaining.

For those prepared to wade through them rather than come across snippets in countless retellings in articles and books by other people, the basic concepts within these books are golden. If you read that the market is a voting machine (moved in the short-term by sentiment), or you read about buying shares with a margin of safety (for less than they are worth), the idea probably originated in one of Graham’s books.

The much less well known The Rediscovered Benjamin Graham is where I discovered Graham properly though. It is a totally different book, an edited collection of his articles, lectures, and interviews. They span his career from the 1920’s to the 1970’s and show how he developed as an investor and thinker, and why his ideas endure.

Perhaps the greatest homage to Graham was an article written by Warren Buffett in 1984 and published in Forbes as The Superinvestors of Graham and Doddsville. Already regarded as a superinvestor himself, Buffett identified other superinvestors who had beaten the market year in and year out. All of them, he said, had one “intellectual patriarch”, Graham.

The first was Walter Schloss, whose “Reminiscence” penned shortly after Graham’s death prefaces The Rediscovered Benjamin Graham.

It all started with Graham

Although Graham has a reputation as a numbers man, the book reveals there was much more to him than the financial ratios and algebra he used in the running of his investment firm. He testified on economic issues in front of the Senate, he taught and mentored generations of investors including Buffett and Schloss, and thought widely about business, the economy, and society.

A speech on The Ethics of American Capitalism delivered in 1956 demonstrates Graham’s enduring relevance. He approved of the swollen role of the state ushered in by Roosevelt and Eisenhower since the Great Depression. Laws and regulation had tempered the laissez-faire principle and limited the influence of the tycoons that had previously wielded enormous economic, political and social power. Tax supported welfare reforms had improved the lot of ordinary people.

Quoting Philip Drucker, a management expert, Graham believed “No policy is likely to benefit the business itself unless it benefits society.”

Today, after decades when maximising returns has been the guiding principle of corporate America and UK Plc, and a new generation of tycoons have risen, we may only just be rediscovering this truth. Hopefully we are.

Investment versus speculation

Part Two of six in the book contains four pieces by Graham on the theme of stocks and shares. They deal with one of his preoccupations: the difference between investment and speculation.

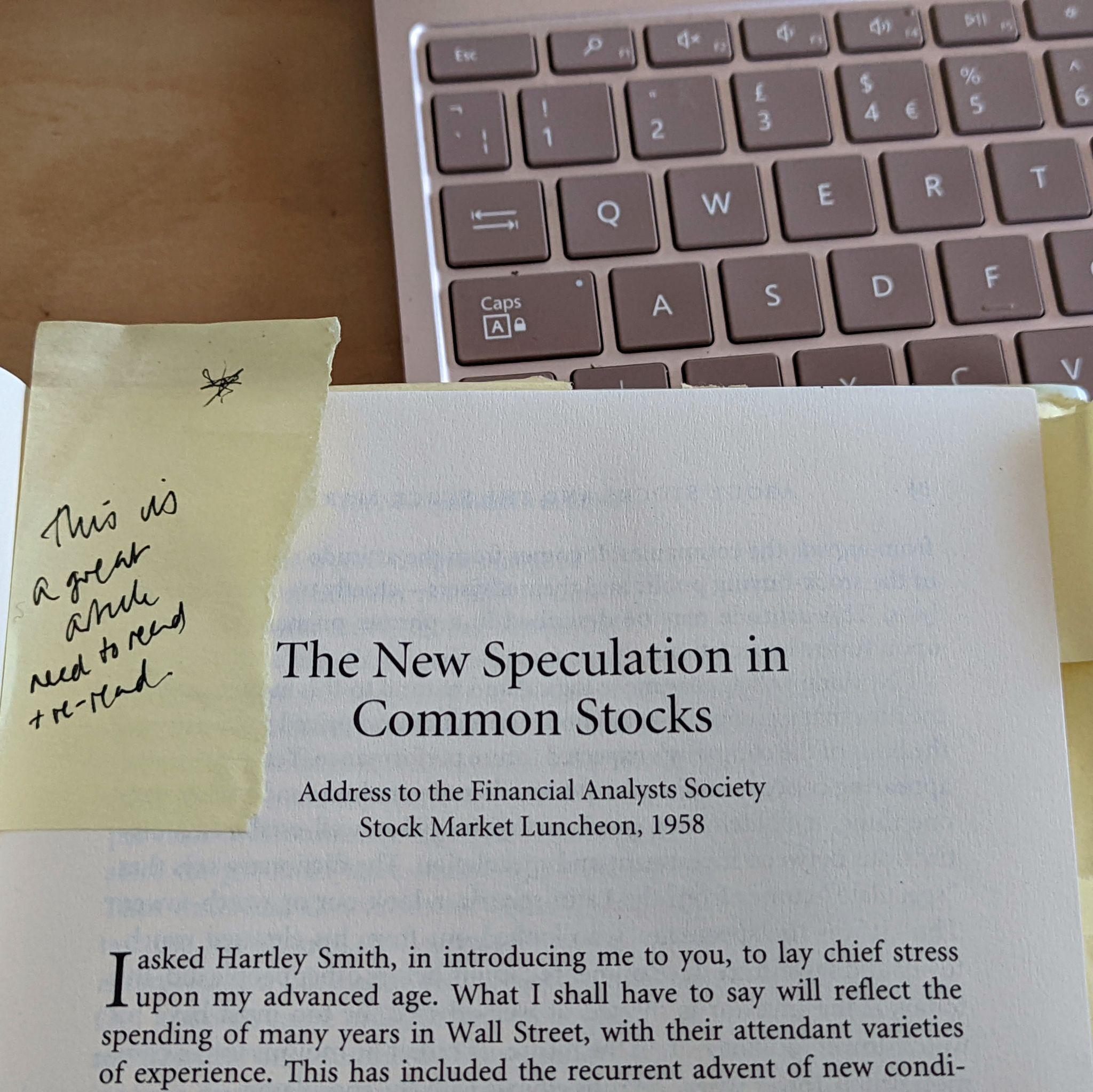

To my delight I have rediscovered a note a younger me left a note to the older me at the beginning of the first of them, the transcript of a speech entitled The New Speculation in Common Stocks. My note says: “This is a great article. Need to read and re-read”:

Graham was putting forward the idea that the nature of speculation had changed. In the past, he said, “the speculative elements of a common stock resided almost exclusively in the company itself.”

“They were due to uncertainties, or fluctuating elements, or downright weakness in the industry, or the corporation’s individual set-up”, he said.

We are still familiar with these speculative elements today, they refer to the cyclicality of some businesses, their disruption by others, and the managerial hubris that can lead companies to overextend themselves and sink under a pile of debt.

Investors at the beginning of the twentieth century, he said, were not considering the potential of companies, only what they could see now and by looking at the recent past.

Between then and 1958, when he was speaking, the attitudes of financial analysts had changed. They had become preoccupied with companies’ expected future performance, as, on the whole, we are now.

Graham did not think this was wrong. There were many examples of so-called speculative issues, unstable businesses with few hard assets, that had gone on to be tremendous long-term investments.

Back in 1916 in his first job on Wall Street, Graham enthusiastically pitched shares in Computing-Tabulating-Recording Co. to his boss. He had used the company’s punch card calculating machines in a previous job.

“Ben,” said his boss, “do not mention that company to me again. I would not touch it with a 10-foot barge pole… everybody knows there is nothing behind it but water.”

Chastened, Graham returned to his statistician’s cubby-hole and never bought a share in C.-T.-R. Not even after it changed its name to IBM in 1926.

Graham, though, recognised that the new attitude, emphasising the prospects of a business over its hard assets, came with its own risks: a new kind of speculation. It allowed investors to make the most outrageous assumptions about how much a company might grow, and discount their guesstimates of its future profits back to present day values to justify buying shares at almost any price.

Today, companies must disclose much more than they did even in Graham’s later years, and often they are often inherently safer investments. However, we are still no safer from ourselves, and the new speculation goes on.

Happy Christmas!

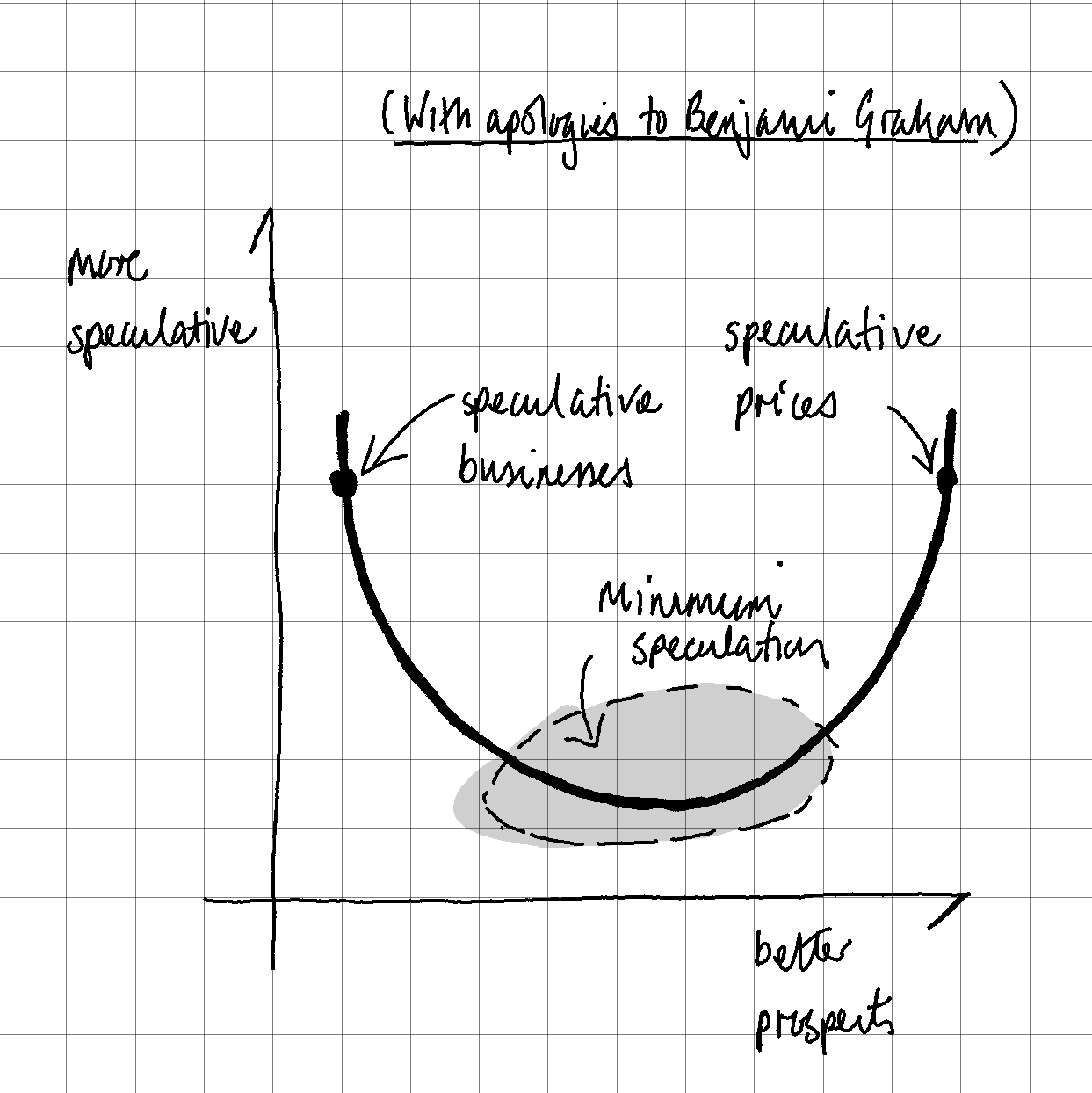

Graham’s view was that firms with excellent prospects trading at very high valuations are just as speculative as firms with very poor prospects. He encouraged his audience to imagine a U-shaped graph. The vertical axis measures how speculative the share is and the horizontal axis represents investor perceptions of its prospects.

Companies with grim prospects are speculative (the top of the left arm of the ‘U’), but so too are companies that are highly rated (the top right arm of the ‘U’).

“It would be in the center area where the speculative element in common-stock purchases would tend to reach its minimum”, Graham said. They are good businesses, and the share prices are not excessive. Since they have not caught traders’ eyes, they may even be undervalued.

If you are scratching your head trying to visualise the graph, you are not alone. Graham’s graph is imaginary, and Google will not fetch you a copy. The first time I read his description I had to draw it out, but I have long since lost that scrap of paper. Recently though, I drew it again, while explaining the graph to a friend, so here it is:

Concluding his speech, Graham gave the final word to Apollo, the God of Greek and Roman mythology, who advised his son Phaeton that he would always go safest in the middle course.

“I think this principle holds good for investors”, Graham said.

And so too it has, ever since. When we hear Buffett talking about growth and value being “joined at the hip”, read Joel Greenblatt of Magic Formula fame advocating buying “good companies at cheap prices”, or read Fundsmith’s commandments to “buy good companies, don’t overpay and do nothing,” we are experiencing Graham’s legacy.

That is it from me for another year, and since for many of us Christmas is a time for coming together, Graham’s advocacy of the middle course seems an appropriate ending.

Happy Christmas.

Richard Beddard

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Hi Richard, there are always enduring lessons from Ben Graham.

I think The Intelligent Investor was the book that got me into value investing way back in 2007 or thereabouts.

The book was mentioned in The Intelligent Asset Allocator and I shall be eternally grateful to the author for mentioning Ben Graham (the father of value investing) in a book that was based on the idea that markets are efficient.

Merry Christmas to you, your family and your fake fire!

John

Happy Christmas John!