Markets lurched downwards at the start of last week, with the FTSE 100 falling to 6,906 before recovering to 7,067. Nasdaq and the S&P also recovered during the week to 15,316 and 4,449 both moving less than half a percent. The FTSE China 50 was down 3.6%, and down 18% since the start of the year, as investors worried about contagion from Evergrande. China’s property market is worth c. 4x GDP, or $52 trillion.

Natural Gas has been the latest commodity to spike upwards +89% in the last 6 months, which has caused problems for UK energy firms and is likely to feed through to inflation. The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee said last week that they expect UK inflation to peak at over 4% and remain there for the first half of next year. Meanwhile in Turkey, President Erdogan is threatening to jail economists who publish inflation statistics that are higher than the Government’s official figures.

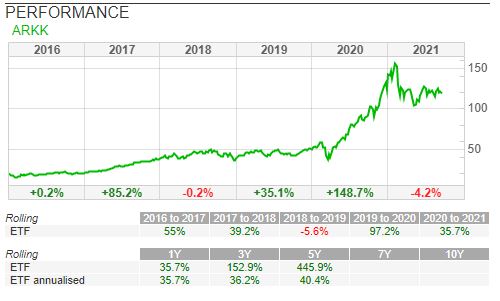

There’s a fun Cathie Wood CNBC interview from last month, where she says that she doesn’t think we’re in a bubble like the late 90’s and that she’s more concerned about deflation. Economists sometimes talk about good inflation (rising disposable incomes) and bad inflation (rising food and energy costs). Instead Cathie talks about good deflation (caused by technology platforms) and bad deflation (companies focusing on short term profits and paying dividends!) This isn’t completely mad, I have concerns about the ARKK risk management (the ETF structure may not protect investors if there’s a sharp sell-off in the fund’s largest holdings), but I think some of the contrarian insights that she generates are worth considering.

Rather than Moore’s Law (the number of transistors on an integrated circuit halves every 2 years) Cathie says her thinking on deflation is influenced by Wright’s Law. Named after T. P. Wright, a US engineer, the law provides a framework for forecasting cost declines as a function of cumulative production. It states that for every cumulative doubling of units produced, costs will fall by a constant percentage.

Wright’s Law is older the Moore’s Law, he came up with it a hundred years ago while studying the production costs of airplanes. The insight is that people tend to underestimate how new technology becomes cheaper as production increases. But this doesn’t necessarily happen at a steady pace over time, it happens because as you make more units, you improve the process and making stuff becomes cheaper. So, taking airplanes as an example, the cost to make the 2,000th plane was 15% less than that to produce the 1,000th plane, and the cost to make the 4,000th plane, was 15% less than that to produce the 2,000th. Fast forward 100 years and because there are so many airplanes and internal combustion engine cars, these aren’t becoming cheaper to make because to double the cumulative production from 1920 would take decades.

Both laws focus on falling costs, but Moore’s Law is a function of time, Wright’s law is a function of units. She points to lithium ion batteries used in Electric Vehicles as an example and using a Monte Carlo stochastic model with 34 inputs, ARKK can justify a $3,000 per share price target on Tesla by 2025 (v $750 per share, $750bn market cap currently).

Investors in technology like ARKK (up +446% in the last 5 years) have certainly enjoyed great returns. But I think the performance has been driven by software, rather than technology more generally. If you look at the top 10 holdings ex Tesla, most rely on network effects and software economics (Teladoc, Roku, Unity, Coinbase, Zoom, Square, Shopify, Spotify, Twilio) rather than Wright’s Law.

You don’t need a fancy law to know that if you can get software right, the pay-offs are marvellous because you can add more users at zero marginal cost (Eg Microsoft Windows, Google, Netflix etc). But this doesn’t apply to technology more generally, an engineering firm like GE hasn’t benefited from the same trends. It is clear to me that there will be significant amounts of money flowing into green energy, hydrogen fuel cells, battery technology, life sciences. But what is not clear to me is whether the economics of successful technology will be as attractive as software has been over the past decades.

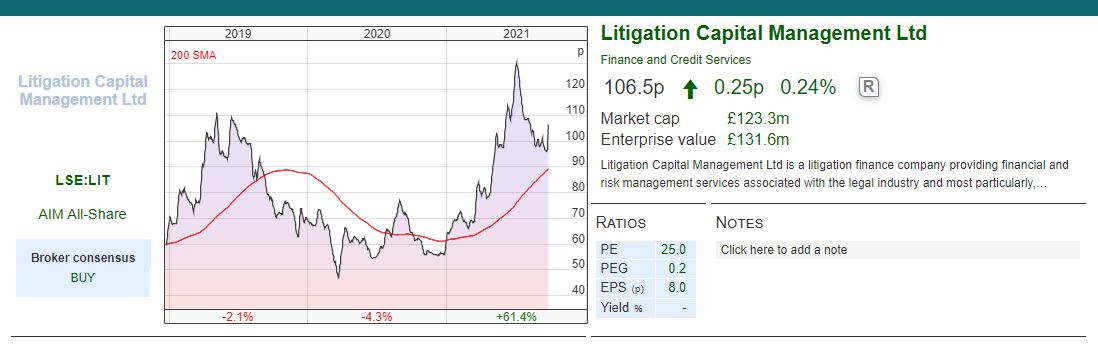

This week I look at a couple of digital healthcare platforms, Open Orphan and Cambridge Cognition, which both reported H1 results last week. Plus Litigation Capital, another sector that didn’t exist 10 years ago where the economics of growth and returns could be attractive, but we’re still awaiting the final verdict.

Open Orphan H1 to June

This vaccine and anti-viral testing company, that describes itself as “world-leading”, announced H1 results to June. ORPH have been loss-making since the company came to market with a reverse listing into Venn Life Sciences in June 2019, raising £4.5m at 6p per share valuing the company at £14m.

This vaccine and anti-viral testing company, that describes itself as “world-leading”, announced H1 results to June. ORPH have been loss-making since the company came to market with a reverse listing into Venn Life Sciences in June 2019, raising £4.5m at 6p per share valuing the company at £14m.

I don’t particularly like loss-making companies that describe themselves as “world leading”, because it implies that the companies “world leading” status does not generate profits. I think you could make a reasonable case that Barcelona is a world leading football club, but it has also been on the verge of bankruptcy according to Spanish newspaper El Mundo. If you are a shareholder in AIM-listed Celtic FC, which is definitely not a world leading football club, that could turn out to be a better investment because, pre-pandemic at least, it occupied an attractive niche and had a decent track record of profitability.

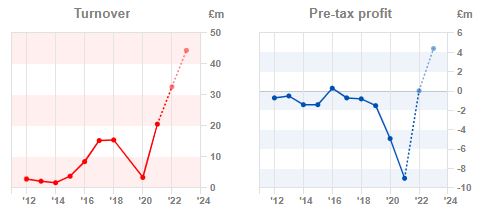

That said Open Orphan has now reported an H1 profit of £1.5m (versus a loss of £6.8m H1 2020). Revenue has more than trebled to £21.9m. Inevitably management prefer to highlight EBITDA before exceptional items which is £2.1m vs a negative £4.1m last year. A quick glance at the cash flow statement reveals that cash from operations was still negative £3.5m H1 2021 vs negative £4.5m the H1 last year. That’s due to a £1.1m deduction of an R&D credit and a £4.5m decrease in payables. Payables were £16.9m in June (all in current assets, so due before June next year) which seems a large number to carry on the balance sheet without any explanation, versus cash of £14.9m. Also worth highlighting from a cash vs accounting perspective, ORPH earns revenue from clinical trial services that can last multiple years, so they’re paid on a percentage completion basis which requires some management judgement. There was £13.7m of accrued income at the FY stage, and £14.5m of contractual liabilities, though I find the company’s disclosure (note 35 of the Annual Report) rather confusing.

Spin offs In June this year they announced that they would demerge Poolbeg Pharma, a clinical-stage infectious diseases pharma company, which would have a different risk profile to ORPH’s services-led business model. Poolbeg then raised £25 million through a placing of new shares at 10p per share, giving Poolbeg a market valuation of £50 million at IPO. Open Orphan then distributed £26m (current value) of “in specie” paper to shareholders on the ORPH shareholder register on 17th June (ie not converting to cash, but giving them shares in the spin off.) There are other drug development assets on the balance sheet, for instance a 49% stake in Imutex (flu vaccine in phase II trial) and a 63% stake in Prep Biopharm (viral prophylactic in phase II trial to prevent respiratory tract infection, potentially useful for treating Covid.) There’s also a data business called Disease in Motion, that has applications likely to be useful for big tech, wearables, pharma and biotech companies. They mentioned DiM in this H1 results, saying that they’ve taken the first steps in demerging.

Ownership There isn’t much institutional ownership of this stock. Retail brokers like Hargreaves Lansdown Nominees own 17.7% and Interactive Brokers 7.7% stakes, suggesting that this stock appeals more to retail investors. They’ve certainly been keen to appeal to that market with Cathal Friel, the Executive Chairman who owns 7%, giving presentations this year to Mello, PI World, InvestorMeetCompany and ShareSoc.

Outlook The outlook statement reads very bullishly, saying the infectious and respiratory disease market is seeing exponential growth, which has “vastly increased” ORPH’s market. The company expects FY 2021F revenue of £40m, with non Covid work expected to represent 70% of the revenue mix.

Valuation Despite the trebling of H1 vs H1 last year revenue, FinnCap ORPH’s broker reduced 2021F revenue by 17% to £38m (previous forecast £46m). The broker is now expecting a small FY 2021F statutory loss, a sharp decline versus £3.4m PBT previously forecast. FinnCap also introduced FY 2022F forecasts of £49m revenue (£50m is mentioned in the company’s outlook statement), £3.3m PBT and 0.5p of adjusted EPS. That puts the shares on 3.1x 2022F revenue and 45x PER.

Opinion The shares had a very strong rally from 6p in March 2020, to a peak of 45p in mid April this year. They’ve re-traced their steps back to 22p. For readers hungry for risk this could be an interesting investment, similar to Ixico and Cambridge Cognition (see below) which also have business models around making clinical trials more effective. All of these companies are providing services to pharma companies, and could benefit from the flood of money that’s likely to flow into life sciences following the virus. But not for widows or orphans.

Cambridge Cognition H1 to June

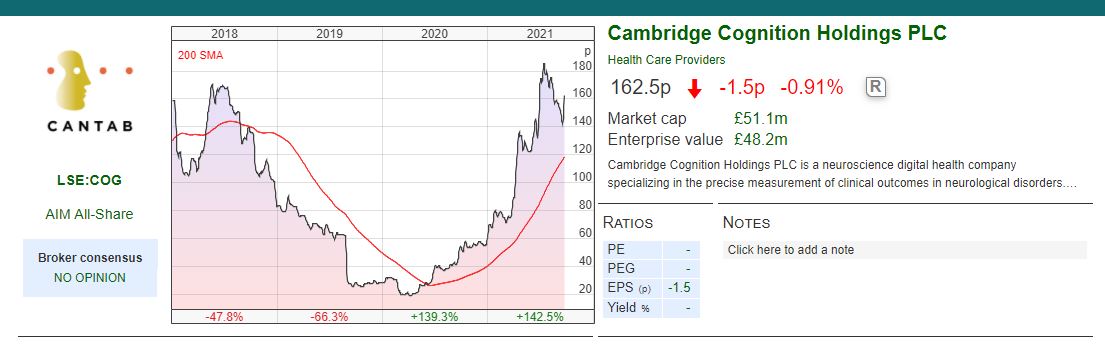

Cambridge Cognition, which has a digital platform to improve clinical trials in psychiatric (eg schizophrenia, depression) and neurological diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, epilepsy) announced H1 to June results. Customers include pharma and biotech companies, but also universities and healthcare providers.

Results were impressive with revenue +50% to £4.5m, gross profit margin maintained at 80% and a small profit of £0.1m vs £0.4m loss H1 last year. Net cash was £4.2m at the end of June. The order book has more than doubled vs H1 last year, and now stands at £15.2m, though management also say that the last couple of years have seen unusually large orders which haven’t been repeated. Like ORPH, the trials can last over many years, so revenue recognition is sensitive to management assumptions.

Spin off During H1 management completed the spin out of Monument Therapeutics, a digital phenotyping business. COG sold 63% to two venture capital firms (Catapult Ventures and Neo Kuma Ventures) but retained a 37% stake. If Monument is successful, it will pay royalties to COG.

Outlook The company suggests that Covid has accelerated a shift to virtual/decentralised clinical trials with self-testing at home (as opposed to less frequent visits to a clinic for testing and data capture.) The company has said that H2 trading has been in line with expectations. Their broker is FinnCap, who left forecasts unchanged: revenue £10.8m 2022F and EPS 0.9p in 2022F, suggesting a price/sales of 4.7x and PER of 180x 2022F.

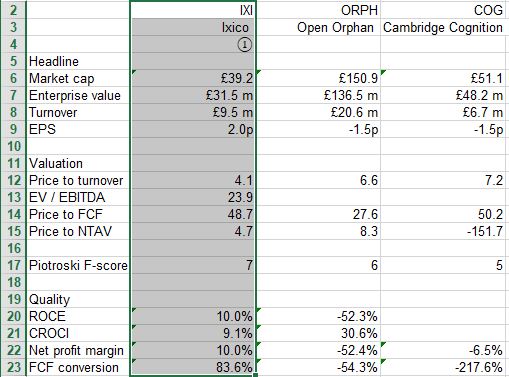

IXICO IXICO which is in a similar space, looking at digital biomarkers to help improve clinical trials, reported a couple of sub £1m contract wins last week too. I wrote about it in more detail at the end of May. Despite losing a large client’s Huntington’s Disease phase III trial, their order book was a healthy £19.5m at the end of June.

Opinion I’m wondering if a rising tide will lift all boats in this sector, or whether it’s important to try and pick a winner. ORPH and COG trade on c. 7x historic revenue, whereas IXICO, at 4.1x is trading on roughly half that valuation despite being more profitable. The difference could be explained by the COG gross margin of 80% and revenue growing at +50%. By contrast IXICO’s H1 to March gross margin was 68% and expects FY Sept 2021F revenue of £8.8m, a -7% decline on the previous FY. I’ve used SharePad’s “compare” button, and then downloaded the data into a CSV file to show the key differences.

ORPH’s gross margin H1 2021 was just 26%, but improved significantly from 6% last H1 after restructuring. I have no position, if you’re keen on valuation then IXICO looks more attractive, but COG is more “growth at a reasonable price” style of investment. I’d suggest the investment case for ORPH rests on your view of the charismatic Executive Chairman.

Litigation Capital FY to June

This Australian litigation finance company published slightly disappointing top line results, with a FY revenue decline of -5% to AU$36.4m, excluding their Global Alternative Returns Fund (AU$150m Assets under Management AU$0.6m contribution to revenue) they set up last year. Gross profit (ie after litigation expenses have been deducted) was up +20% and statutory PBT was up +42% to Au$13.1m (ex TPF). Importantly LIT reports under Australian Accounting Standards, and revenue is only recognised when they have an unconditional right to their money (so, unlike Burford, they don’t mark up the value of cases using Fair Value accounting).

The company reports a 10-year ROIC on completed cases of 153%, up from 134% FY 2020. That figure also compares favourably to Burford’s ROIC of 95% (to H1 June this year). Committed capital, the amount of money that LIT commits to disputes, fell -26% to AU$109m. That is despite LIT receiving +10% more applications in the FY to June 2021 versus the previous year. The Chief Exec says that the fall in commitments was due to disruption to the “due diligence” process evaluating disputes, caused by the pandemic. I’m slightly surprised by this explanation, particularly as Burford reported commitments up strongly by +334% to $503m H1 2021 vs H1 2020.

Valuation I don’t think that you can forecast this business 2-3 years out, and then put an earnings multiple on that figure. Even internally the company has no visibility when cases will reach a resolution. Even if they can be reasonably confident of winning the cases that they take on (win:loss ratio is 226:11 or greater than 95% wins in percentage terms) they don’t know the amount of money that they will be rewarded. However, because LIT uses historic cost accounting, we can do a Return on Equity calculation. On this basis LIT reports a not particularly impressive RoE of 10.4%, only a couple of percentage points above the company’s cost of equity. But I think that RoE is suppressed because they raised AU$42m when the company delisted in Australia and moved to AIM in December 2018.

That suggests some premium to book value AU$90.1m (£48m) is probably justified. But at 106p per share, the premium is 2.6x which using a Gordon Growth Model implies investors believe profitability is going to increase towards 20%.

In financial valuation models, there is an assumed relationship between growth and returns: management face a trade-off between increasing growth or increasing profitability. In reality the world is rarely so simple. Some highly profitable companies (GAW between 2010-2016 struggle to grow the top line) and some barely profitable companies exhibit very high top-line growth (KAPE). Litigation finance is a fast growing sector, but it’s not clear whether increases in revenue are generating future value for shareholders “through the cycle”.

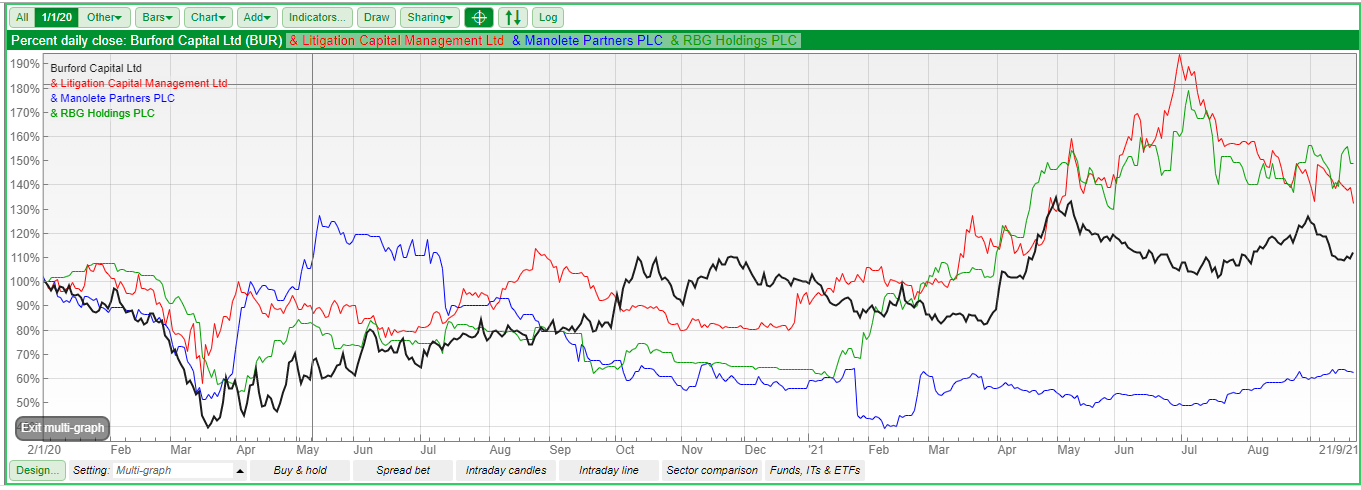

Opinion These companies were supposed to offer uncorrelated risk to the market. Using SharePad’s multigraph feature, we can see in the chart below a large divergence in performance since the start of 2020. That’s mainly been caused by different business mix, with LIT and BUR behaving as conventional funders. Manolete, which released a short AGM statement last week, has been the worst performer, hurt by the suspension of insolvencies.

The winner (so far) has been RGBP, which has been helped by more diversified revenue from the buoyant corporate finance conditions, as they bought Convex Capital last year.

Bruce Packard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Please explain the recent sudden steep fall in value of Spirax-Sarco Engineering PLC shares, desoite the recent excellent half year resits and a bullish outlook