Inspired by Maynard’s article on Hornby’s turnaround, Richard examines the history of Games Workshop to imagine what challenges lie ahead if Hornby is to emulate the success of this outwardly similar hobby business.

The idea for this article came from Maynard’s article about Hornby. To my mind he convincingly described a turnaround that is already underway.

To whet our appetites of what might lie ahead, Maynard mentioned “wonder stock” Games Workshop, also a hobby business, and an example of the kind of change in financial and share price performance that is possible when a good business turns itself around and subsequently prospers.

As a long-time shareholder in Games Workshop, I was struck by the similarities between the two companies, and suppose that by examining Games Workshop shares history in more detail we might better imagine the challenges that lie ahead for Hornby.

A tale of two hobby Stocks

Hornby designs models and toys. Games Workshop invented a hobby called Warhammer which also involves making, collecting, and playing with models, model soldiers.

For both kinds of hobbyist, modelling and playing or collecting is not a childish pursuit. These are hobbies adults enjoy. Indeed, the adults are usually the big spenders.

Maynard laid out Hornby’s more chequered history in detail, but to summarise, it overextended itself. Surprising though it may seem now, Games Workshop has made losses in the past, and for a similar reason.

The last time Games Workshop made a loss was in 2007 after it had licensed the rights to make miniatures and a game using characters and stories from The Lord of The Rings.

Inspired by the films, legions of fans bought the miniatures. Games Workshop recruited more staff, and expanded its stores to accommodate a third product line alongside its own Warhammer fantasy and science fiction-themed miniatures and modelling and game kits.

But as the commotion around the films died down, so did Games Workshop’s custom. Revenue stagnated but the business had much higher overheads.

The first part of Games Workshop’s turnaround involved cutting those overheads: it reduced the cost of making the miniatures by making them from plastic instead of metal, it reduced most of its stores to one person operations, and it refocused on Warhammer, reducing the resources it spent developing and marketing The Lord of The Rings products.

Hornby, which bought other businesses as well as many licenses, diworsified further, and its hangover has been more brutal.

But Maynard tells us that under new management, Hornby has stopped licensing and acquiring brands. In other words, like Games Workshop, it is focusing on brands that it already owns. That is probably the reason Hornby’s financials are turning a corner.

The big question is what happens next? There may be more upside for shareholders in the turnaround, but investors with long-term horizons will be wondering whether this time Hornby will keep growing indefinitely or it might fall off the rails again.

Games Workshop’s turnaround

The essence of strategy is to decide what challenges a company faces and devise a set of coherent actions to overcome them.

Hornby’s recent annual report contains great detail on its improving key performance indicators, statistics that tell us how efficient the company is. From these it is clear the focus of Hornby’s strategy is to right the ship and deliver its stated aim to be cash flow positive next year.

But the company is not explicit about its strategy, and apart from these internal measures, it says very little about how it plans to make more money in future.

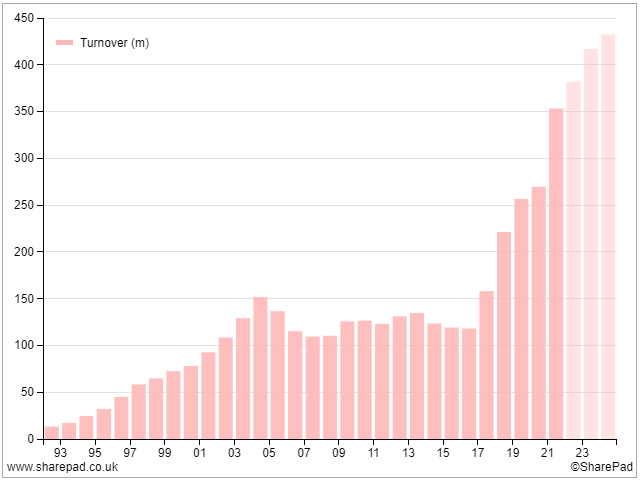

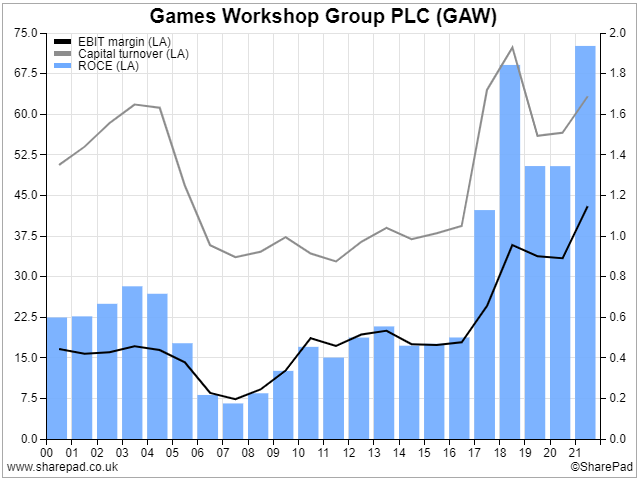

Games Workshop did not just turn itself around, it became a much bigger and more popular business than it had been before. Changes, perhaps long in the making, combined in the last six years to ignite hobbyists’ passions:

It also became a better company, because it is much better at turning elevated turnover into profit:

It took Games Workshop eight or nine years from its failure in 2007 to come out of its shell. The company’s former executive chairman Tom Kirby, who masterminded Warhammer’s original rise to fame, came a cropper over The Lord of The Rings, and then restored the company to consistent profitability, was not the man to complete the job.

Games Workshop blossomed after finance director Kevin Rountree took over as CEO in 2015.

By 2015, Games Workshop was beginning to look outward again, starting with its own customers, many of whom had fallen out with the company rather spectacularly.

The lighter plastic models had enabled elaborate designs, which Games Workshop could charge more for. These models, costing up to £1,000, appealed to a small well-heeled coterie of hobbyists.

A year or so earlier, I spent a few hours in a Games Workshop hobby store (now they are rebranded Warhammer). While I was there, a customer confided to the manager how he hoped to win back nearly £400 he had just spent by winning a modelling competition, only then would he reveal how much he had spent to his wife.

I also attended an AGM where Tom Kirby told me most of the company’s best customers had long given up fighting Warhammer battles. They were adult collectors.

To my mind, and that of many of the still passionate gamers venting their frustrations in online forums, by letting the game wither on the vine, Games Workshop was killing the goose that lays the golden egg.

The original Warhammer game, Warhammer Fantasy Battles, had lost its allure and in the same year that Rountree became CEO, Games Workshop tore up the rule book, replaced it with a single page of rules that were free to download, and blitzed the backstory.

Starting over, it borrowed elements from its more successful sibling, Warhammer 40,000, which is set in the far future. The new fantasy game, the universe it was set in, and the characters and scenarios, was called Warhammer Age of Sigmar.

Games Workshop re-engaged with its customers by creating Internet content. Some of it is similar to the content on Hornby’s YouTube Channel: “How-to” videos on modelling techniques, teasers for products and trips behind the scenes in the design studio.

It produced entry-level kits at affordable prices, to ease new hobbyists into modelling and gaming. And it stepped up the release of new characters, scenarios, and editions of both Warhammer Age of Sigmar and Warhammer 40,000.

Can Hornby “do a Games Workshop”

At first blush, it seems that Hornby could borrow from Games Workshop’s playbook. Frankly if it were quarter as successful it would still be a great investment today.

But before we get carried away with the scenario that one hobby company might replicate the success of the other, we should consider the differences between Games Workshop and Hornby.

Wargaming is a collective activity. To play the game you need other hobbyists, who have spent money on the models and time learning the lore. The more gamers there are, the more potential gamers are exposed to it.

Railway modellers have clubs and exhibitions, but it is a more solitary activity, and the interactions of hobbyists probably exert a less powerful network effect.

Railway modelling is also more parochial. Games Workshop’s imaginary worlds appeal to large numbers of people all over the World. The LNER, A1 Class, 4-6-2, 4472 ‘Flying Scotsman’ and the Supermarine Spitfire Mk. 1, perhaps less so. Hornby owns overseas brands, like Italy’s Lima, but these too probably have more limited appeal outside their home markets.

Games Workshop is a vertically integrated business. It manufactures in Nottingham, the same place it designs them. The company’s headquarters is located there too. It sells the miniatures from its own stores, which it says are its best source of new recruits, its website as well as through independent hobby stores.

Stories set in Warhammer’s imaginary worlds are told in thousands of books, written by Games Workshop authors, and published by Games Workshop’s imprint. Animated series are commissioned by Games Workshop and streamed from its websites. They form part of the new Warhammer+ subscription.

Vertical integration gives Games Workshop almost absolute control of the product and enables it to profit from almost every aspect of it. It is one of the reasons the company is so unique.

Hornby is not vertically integrated. It designs models that are largely manufactured in China. It does not operate physical stores either. But perhaps most importantly demand for Hornby’s models is not story-driven like demand for Games Workshop’s miniatures.

Warhammer game scenarios, novels, animated series, video games, and a TV series in development, drive customer’s enthusiasm for new miniatures, which is why it is often compared to film franchises like Marvel. And like Marvel, Games Workshop can reinvent its characters and stories for each new generation.

Hornby’s intellectual property is rooted in brands with nostalgic appeal. The number of us who can remember the age of steam, which accounts for much of Hornby’s appeal, or the Second World War, which accounts for much of Airfix’s, are shrinking.

Each successive generation feels less connected to the source material.

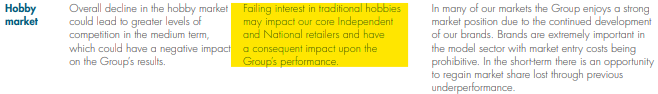

While Hornby is not explicit about its strategy, it is explicit about one of the challenges that strategy would need to address, which is falling interest in traditional hobbies.

Source: Hornby Annual Report 2021

The thing that kept me interested in Games Workshop in the wilderness years when the business had turned itself around but was not growing convincingly, was the idea of the golden egg: That Games Workshop’s fantasy worlds had, if not limitless, then enormous potential.

Games Workshop has always maintained that its biggest risk is internal – that it will lose focus like it did in 2007. In a sense, all it had to do was refocus and give customers what they wanted to flourish.

I do not think that was easy by any means, but it may be that for Hornby to flourish to anything like the extent that Games Workshop has, if it is to become more popular as well as more efficient, its strategy will have to be more radical.

Richard Beddard

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Hi Richard, very interesting.

I hadn’t really thought about the network effects in Games Workshop’s business model. If you’re going to get into a hobby where you play or compete with other people, then the fact that lots of other people play a given game will make that game more attractive.

I guess it’s the same with football: It’s popular because it’s popular.

I haven’t looked at either company in detail, but my initial feeling is that I sort of agree. It seems unlikely that Hornby can ever have much of an international appeal, given the backwards-looking and localised nature of its product.

Games Workshop on the other hand, as you point out, lives in the world of infinite fantasy and speaks the international language of war, guns, swords, orcs, elves and so on.

However, I also think it’s far too soon to assume that Games Workshop is anything like Marvel. I’m not saying it couldn’t be, but there the world is littered with the graves of a bazillion collectables and models businesses, so five years of very rapid growth for Games Workshop isn’t anywhere near enough to draw any longer-term conclusions.

After all, GAW did go pretty much nowhere from 2002 to 2014.

Also, with an earnings yield of 3%, investors must be assuming very rapid growth for a very long time. They could be right but it all seems a bit optimistic to me. But then I’m just a grumpy old value investor so that’s what you’d expect me to say!

John

Hi John, thanks for your comment.

Well I don’t think Games Workshop is a just a collectibles business for the reasons mentioned in the article (many of which you have summarised articulately), in fact I think having been burned by The Lord of The Rings escapade, management initially retreated into that mindset for a while so the damage of the over-expansion was compounded by a subsequent lack of ambition for Warhammer.

There is definitely a discussion to be had about valuation though. That wasn’t in the scope of the article as I was really just giving my opinion on whether Hornby is likely to “do a Games Workshop”. I think Games Workshop is fairly priced and ought to be a good long term investment.

I think the share price is most unlikely to perform as well as it has over the last five or so years. That would be asking a hell of a lot!