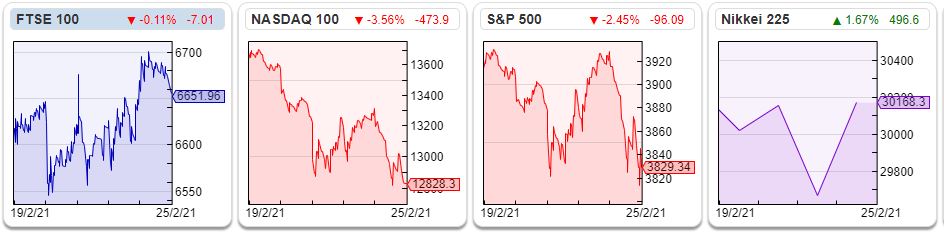

Nasdaq sold off last week, down 7% since the middle of February, though still up since the start of the year. Tesla fell to $680, versus a peak of $896 earlier in February. US 10y yields hit 1.49% last week up over 50bp in the last month

Financial bubbles don’t pop because speculators suddenly start worrying about valuation; everyone knows that internet stocks, negative yielding bonds, impressionist paintings or tulips are overvalued beyond their fundamental cashflows. Instead the bubble pops because there is a sharp reappraisal of liquidity assumptions, the price that a speculator can sell at as everyone else rushes for the exit at the same time.

I’m going to enjoy watching (from a safe distance) how Cathy Wood’s ARKK innovation ETF copes with outflows. Her “active” Innovation ETF has grown to $25bn, and total amount of ETFs (eg genomics, fintech and next generation internet ETFs) managed by ARK group has grown from $3bn to $60bn in the last year, according to the FT. Even as the Tesla price fell last week, and she saw outflows, she bought more Tesla.

Promoters of ETFs have claimed that the products work well even when their underlying holdings are illiquid. The mechanism that provides ETFs with liquidity is that market makers (called “Authorised Participants” APs) are allowed to create and redeem shares to match fund inflows/outflows. This means that (in theory) the ETF manager never becomes a forced seller of illiquid assets, because the APs are incentivised to track the market price of the ETF NAV v the price of the underlying assets, and if the gap between the two is greater than (roughly) 1%, the APs can create / redeem shares to bring the two values back into line. That is how it is supposed to work, according to the CFA textbook. But I finished the CFA in 2004, and there was a section at the time on how CDOs create AAA rated assets with low risk of default from subprime mortgages, by creating different loss tranches. I hope the CFA Institute have re-written that CDO section of the text book following the financial crisis.

I’m generally in favour of innovation. But when it comes to financial “innovation”, very often we see a repetition of the same behaviour over and over again. A new financial product appears to function well in liquid markets, until it is tested to destruction by financial promoters (junk bonds, CDOs and now ETFs?) There is nothing new under the sun. What has been, will be again. Perhaps Ecclesiastes should have written the CFA textbook.

One of Cathy’s competitors, who also has done well investing in Nasdaq stocks but not via ETFs has been warning about this for a decade. Terry Smith, is like me, a former UK banks equity research analyst. I’m making a wild assumption that if we do see a tech sell-off, the hot money that has flowed into Tesla, Nasdaq, ARKK and Scottish Mortgage IT is not going to remain sitting idly on the sidelines earning 0.1% in a current account. It seems far more likely to me that we see sector rotation, with money flowing into the beaten up sectors such as banks, oil and mining, emerging markets which are perceived to benefit from “reflation”.

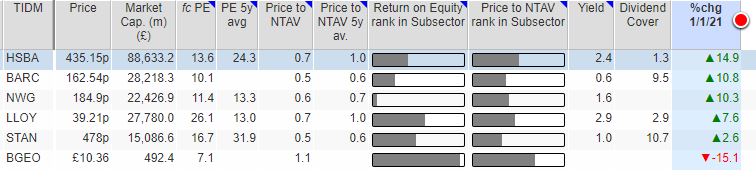

UK banks’ share prices (ex STAN and BGEO) are up between 8-15% since the start of the year, helped by a steepening yield curve and encouraging FY results. So I take a look at what these results are telling us.

UK bank results Barclays reported revenue growth of 1%, while HSBC, Lloyds and NatWest reported revenue down -10%, -16% and -24% respectively FY2020 v FY 2019. NatWest reported yet another statutory loss (the bank’s 9th FY loss since the 2008 financial crisis). At £10.8bn, NatWest’s Total Income is now lower than it was 20 years ago, before Sir Fred’s expensive international shopping spree that culminated with the disastrous purchase of ABN Amro, for which UK taxpayers picked up the (buy now, pay later) cost. The bank’s revenue looks set to shrink further as they sell off Ulster Bank, in the Republic of Ireland. HSBC revenue hasn’t done much better at $50.4bn FY 2020, which is lower than the figure reported in 2004. HSBC’s international ambitions have also been shrinking, selling off operations in Brazil in 2015 and now leaving US Retail Banking and reportedly putting a price tag of €1 on its French operations.

Unlike NatWest, at least HSBC, Barclays and LLOY were profitable, although they reported a miserable Return on Tangible Equity of 3.1%, 3.2% and 2.3% respectively. The current discounts to book value suggest investors are sceptical that returns will ever recover to higher than banks’ cost of equity (roughly 10%). There is a certain irony in the capitalist system that now that regulators require banks to fund more of their lending with equity, the banking system struggles to make a return. Corporate profit margins for the rest of the stock market are at an all-time high (and have remained well above trend for a number of years), but bank profitability (RoE, Net Interest Margins) is at a low.

2020 was clearly a difficult year, 2021 should see bad debt impairments fall away rapidly, also helped by a steeper yield curve, as the vaccine roll out and Boris’ roadmap to reopening continues. So bank profits should improve this year. I remember that in the olden days banks were perceived as boring and somewhat defensive investments. While the FTSE 100 halved between 2000-2003, Royal Bank share price doubled. What has been, may be again.

Barclays reported Fixed Income Currency and Commodities (FICC) +53% FY 2020 v FY2019. Equities were up +31%, and management wanted to highlight that they have grown market share to 4.9% of global banking and markets sector. This is rather laughable, with a very strong tailwind the old Barclays Capital business has generated a Return on Tangible Equity of 9.5% FY 2020. Given how well senior management and traders have been paid, this seems a very expensive way for shareholders to generate a mediocre return. I’m sceptical that any bank has a “moat” in global investment banking. Instead the high RoE reported pre financial crisis in banks capital markets divisions were due simply to mark to market accounting and huge leverage and hidden risks that had built up on banks’ balance sheets. This is a great business if you’re a senior employee, but not for shareholders. 2021 has started well, with junk bond yields falling below 4% and record issuance, but I think Edward Bramson the activist investor is right to question the viability of FICC and equities divisions at Barclays.

By contrast NatWest Markets, which is shrinking, saw revenue fall -16% and once again the division reported a loss. NatWest did put up an interesting slide showing that at the peak Covid crisis, 22% of their mortgage book (or £33.6bn) was on a payment holiday. By Q4 2020 this had fallen to 1% (or £2.4bn) suggesting that banks mortgage books are performing surprisingly well. 11% (£12.9bn) of NatWest’s commercial loan book was on a payment holiday but this has now fallen to 4% (or £4.1bn) as most businesses that are not pubs, restaurants and hotels can service their loans. Lloyds reported £68bn of payment holidays (or 15% of total loan book) at the peak, which has now fallen to £6bn.

Companies covered this week Three companies that I covered at Mello (Bank of Georgia, Georgia Capital and Sylvania Platinum) reported results this week. Sylvania and BGEO are trading on around 5x 2021F PER, and are forecast to report RoE above 20%, while Georgia Capital is trading at a 50% discount to its NAV. These are very far from “bubble” valuations.

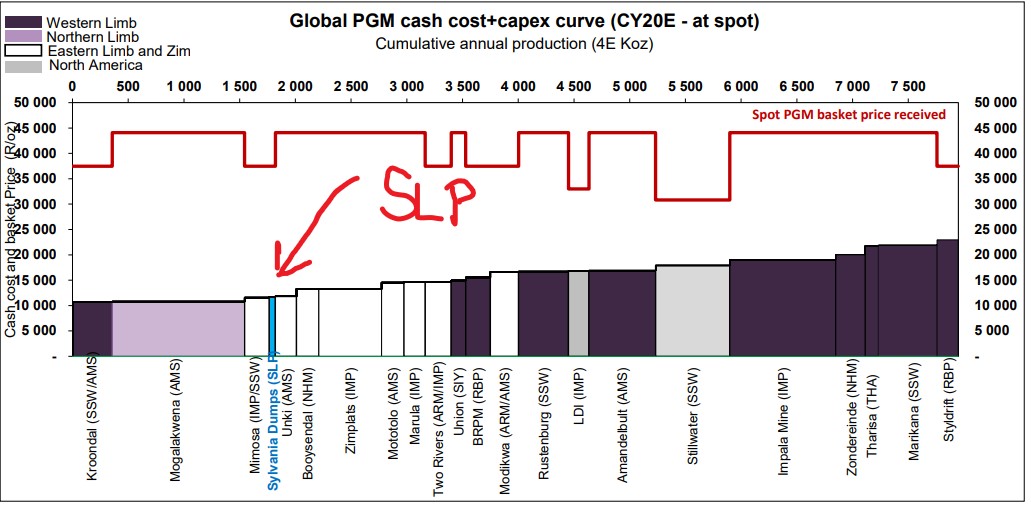

Sylvania Platinum

This South African platinum company released H1 results, with revenue up +44% to $85m and net profit up +70% to $40m. Cash balance was $67m, or 15% of SLP’s market cap. That +44% revenue growth was despite processing 9% less of Platinum Group Metals (PGMs), but the company has been helped by rising PGM basked price +70%, driven particularly by palladium and rhodium. The company has declared a “windfall” dividend of 3.75p, or $14.6m.

The investment case for Sylvania is that it’s not actually a platinum miner. Instead it has a process for working on chrome tailings, so because it doesn’t dig platinum directly out of the ground, the company has a structurally lower cost base. The chart below which comes from slide 17 of the company’s H1 presentation uses data from Nedbank to show that SLP’s “all-in” cash cost of $801/oz is bottom quartile compared to the rest of the platinum mining industry. SLP management said in their outlook statement that they expect to produce 70k oz FY 2021 to June, roughly 50x less than the 3.4m oz for Implats the largest producer and 1.1% of the 6m oz total mining supply for 2021F according to the World Platinum Investment Council. That means that although SLP is small in the context of the other miners like Implats, Sibanye and Anglo, they enjoy a cost advantage.

One slight concern is that despite H1 operating profit of $57m, net cash only increased by $2.4m before currency movements (SLP benefitted from a weak US dollar, because most of its cash is held in Rand which was an $8.8m benefit in the last six months). The reason for the weak cash conversion is a huge $40m jump in trade receivables to $67m Dec 2020 v $27m June 2020. Management say this was as a result of the increase in the gross basket price of PGMs and the four-month payment pipeline in terms of the off-take agreements. That sounds like obfuscation to me. SLP shouldn’t be taking credit risk on the receivables, but I thought that it was worth flagging.

The other concern is chrome feed grade. SLP sources chrome tailings from Samancor, but as commodity prices have been depressed, the quality of feed grade has been falling (SLP’s input material). Management point to some signs of a recovery in the chrome market, but the scaled-down operations at selected host mines mean that over the next 6 to 12 months this will continue to be an issue. That said in the outlook statement SLP reiterated their FY2021 production target of 70k ounces (v 36k 4E PGM ounces in H1). Commodities generally have been performing well, partly because Chinese industrial production hasn’t been as affected by Covid-19 as the rest of the developed world, and partly because commodities are priced in dollars which has been weak since the vaccine was announced.

History The company originally had a dual listing (Australia and AIM) since 2006, but now is only on AIM. Before the financial crisis the shares reached 150p, but then fell to below 10p a share in 2015 as the company struggled to generate a profit on turnover of c $50m. Given it is a low cost producer, it hasn’t really been affected by the low platinum price, which has been trading below $1000 an ounce since the Volkswagen Dieselgate scandal in 2015. As production in Sylvania Dump Operations (SDO) has increased, FY 2021 revenue should be around $170m, PBT around $116m, helped by the increase in price of the non platinum metals in the basket (Rhodium hit $20 000 an ounce earlier this year). During the March 2020 Covid sell off platinum fell below $600 an ounce, but has now more than doubled from its low to $1294 an ounce.

Ownership Africa Asia Capital, a holder for the last 10 years, have been selling down their stake recently from above 20% to 15.88% most recent notification. Miton hold 7% and Fidelity 6%. M&G used to be a large shareholder, but Tom Dobell has now left the fund manager and it looks as though the stake has been sold. 25% of SLP shares are not in public hands.

Opinion I think it’s wrong to see SLP as a play on commodity prices; given the lower cost base SLP is less exposed to the cyclicality of the commodity cycle. For example Implats are seeing a +600% bounce in basic EPS due to the recovery of commodity prices, compared to “just” +77% EPS for SLP H1 2021. So for me, rather than a target price I think about the asymmetric risks for SLP: the company will do well if commodities do well (but not as well as higher cost competitors with operational leverage). But if the platinum price falls back below $1000, SLP should still have over $100m cash in 6 months (25% of market cap) and we can be very confident the company can still generate a decent profit, even at lower PGM prices when the rest of the platinum miners are losing money.

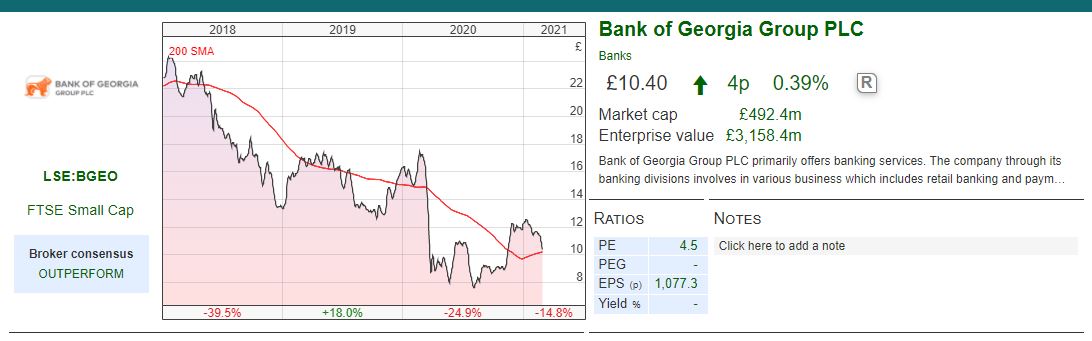

Bank of Georgia

BGEO reported FY 2020 revenue down 2% in Georgian Lari, and FY PBT down 45% to 316m Lari (£67m). Unlike the UK banks FY 2020 RoE was an impressive 13%. Having taken a “kitchen sink” provision (technical banking term) of Lari 241m in Q1 of 2020, the first quarter represented 80% of FY 2020 Lari 301m bad debt impairment charge. RoE was above 20% for the remaining 3 quarters of 2020.

A couple of weeks ago I presented this stock at Mello. I pointed out that there are only two ways that banks can report a high Return on Equity I) make the numerator, the “returns” high ii) make the denominator low, reduce “equity” funding.

Ahead of the financial crisis UK banks were reporting 20% plus RoE, but they were doing that with wafer thin Net Interest Margins (just 1% NIM in the case of Northern Rock). So to report a high RoE, banks mis-sold Payment Protection Insurance and shrank their equity funding as a percentage of their liabilities, until we had the banking crisis. Then after the financial crisis regulators banks stopped selling PPI, and the regulators forced them to increase the denominator again, the “equity” of RoE had to rise, but net interest margins didn’t rise, so it’s no wonder RoE has been very disappointing in the UK. All this was obvious 10 years ago. But professional fund managers don’t tend to react well to anyone who points out flaws in the investment case of assets they are holding. Such a psychological bias goes back in time at least as far as Laocoön suggesting the wooden horse left by the Greeks was not to be trusted.

Bank of Georgia on the other hand has a Net Interest Margin of 4.6% FY 2020, and therefore I think the RoE above 20% can be sustained as long as competition doesn’t reduce lending margins too far. It is true that NIM has fallen from 7.3% 10 years ago, but I think that there are good reasons to believe that the banks margins won’t fall so low that BGEO struggles to report an attractive Return on Equity.

At Mello I explained that before the financial crisis UK banks tried to pretend that their attractive RoE was due to brands (adverts with black horses or sponsoring the cricket) and therefore 20% RoE was sustainable. Of course, it was all nonsense; brands don’t work in banking – no one says “oh, I’d like to borrow hundreds of thousands of pounds to buy a house, and bank A offered me the best interest rate, but I’ll go with the more expensive loan from bank B, because I like the black horses and the music in the adverts”. I don’t think so!

Instead, what does make a difference to bank returns is market share, and as a rule of thumb it’s much better to own a bank in a small fast growing country with a concentrated marketshare (think Singapore or Hong Kong Banks) than a bank with a big market but a small market share (eg German banks, Barclays Capital in global markets). This is only a rule of thumb, it’s not always true that banks with high market shares in fast growing markets do well (Irish banks!) but it works most of the time.

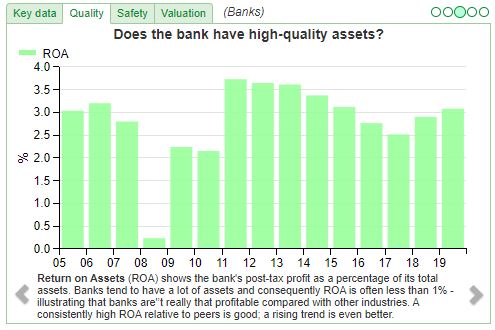

Pre-Covid Bank of Georgia was reporting a RoA above 3% FY 19 compared to just 0.3% for Barclays and Lloyds FY 19.

So my investment case for Bank of Georgia is that it has a 1/3 market share, which means the high Returns on Equity of 20% are sustainable, plenty of room to grow at 15% a year (GDP per capita around $5,000) and the bank is trading on around 5x PER. In Georgia there is no equivalent of HBOS or Northern Rock, funding dumb loans through the securitisation market. I’ve owned this stock for 10 years, and I think we should see both continued profit growth and eventually a re-rating as investors appreciate the high market share.

Georgia Capital

This curious Tbilisi based company is a spin-off from Bank of Georgia also reported FY 2020 results last week. When the financial crisis hit in 2008 and Putin invaded, the bank was left with various businesses as collateral to defaulted loans. A few years later the National Bank of Georgia (ie the Central Bank) asked management to spin-off these businesses into a separate listed entity. They consist of a rather eclectic mix of hospitals (19% of NAV), pharmacies (19% of NAV), insurance (9% of NAV), a water utility (16% of NAV), renewable power (hydro and wind turbines 7% of NAV) and a school (3% of NAV). The hospital business was previously listed in London, but after the Dubai based NMC hospital fraud, they found very little investor interest from London investors, so they’ve reversed into the CGEO listing. They have also retained a stake in London listed BGEO which at 31 Dec share price is (18% of NAV). There used to be a property developer, a vineyard and a brewery too, but I think they must have been written down and are in “other” (ie less than 10% of book value).

This curious Tbilisi based company is a spin-off from Bank of Georgia also reported FY 2020 results last week. When the financial crisis hit in 2008 and Putin invaded, the bank was left with various businesses as collateral to defaulted loans. A few years later the National Bank of Georgia (ie the Central Bank) asked management to spin-off these businesses into a separate listed entity. They consist of a rather eclectic mix of hospitals (19% of NAV), pharmacies (19% of NAV), insurance (9% of NAV), a water utility (16% of NAV), renewable power (hydro and wind turbines 7% of NAV) and a school (3% of NAV). The hospital business was previously listed in London, but after the Dubai based NMC hospital fraud, they found very little investor interest from London investors, so they’ve reversed into the CGEO listing. They have also retained a stake in London listed BGEO which at 31 Dec share price is (18% of NAV). There used to be a property developer, a vineyard and a brewery too, but I think they must have been written down and are in “other” (ie less than 10% of book value).

Given the complexity of understanding all the moving parts, versus the size (market cap £250m) I doubt any professional fund manager will take much time to look at it. But the shares are trading at a 50% discount to NAV 48 Georgian Lari per share (£10.20 per share). Readers may wonder if the NAV can be relied upon, but it has been independently verified by Duff & Phelps, the valuation firm in line with International Private Equity Valuation (“IPEV”) guidelines. D&F looked at the larger, later stage holdings (health care, pharmacy, insurance company, water utility) which are 64% of the total portfolio, and adding BGEO which is listed to the NAV calculation means that 82% of the total NAV has been externally verified. Over the next 18-24 months management are looking to sell one of their larger businesses, which assuming they do so at a price at NAV (or above) should give investors some confidence that book value can be realised. Net debt is 700m Lari (£150m) versus a market cap of £250m.

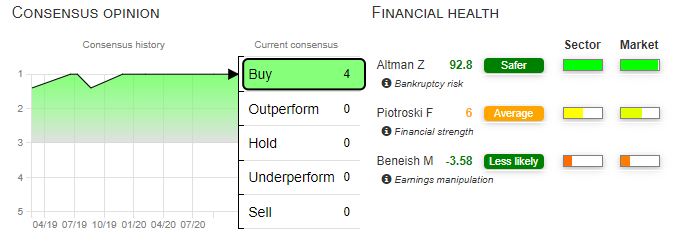

Analyst opinion, Altman Z, Piotroski F score and Beneish M score are all favourable.

I own the shares, and have a lot of time for the Chief Exec Irakli Gilari who used to run Bank of Georgia when we listed it on the London Stock Exchange. Georgia Capital has the characteristics of investing in a listed Private Equity fund in an emerging market, management are focused on cashflow, ROIC and selling businesses at a favourable time. Jeremy Grantham points out that though there might be many “bubble” stocks in the S&P500, emerging markets relative to the S&P500 have never been cheaper. My sense is that we could see significant growth in book value, and if not it’s hard to believe that buying at a 50% discount to NAV investors will lose money.

Bruce Packard

The author owns shares in Bank of Georgia, Georgia Capital and Sylvania Platinum

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

A very awesome blog post. We are really grateful for your blog post. You will find a lot of approaches after visiting your post.

top online casino in the philippines