“Fad companies are companies with good business models or good products. So, why would we be interested in shorting a company that has a good product? Because of the threat it presents to others and their likely response to that threat. For example, Netflix had a terrific idea of renting DVDs through the mail, which was much more efficient but obviously a terrific threat to Blockbuster. One had to anticipate that Blockbuster would respond. Amazon, which has the capability of this kind of product, also entered the business. So, what was once a good business model changed.”

David Rocker CFA Conference Proceedings 2005.

We are coming into Q3 reporting season for US technology stocks. Given that expectations are so high, it’s tempting to believe that high returns are not sustainable. The above quote from a short seller 15 years ago, shows that may be a mistake. It’s now clear that Netflix enjoyed a structurally lower cost base (no video stores), and however Blockbuster responded they were likely to lose. I think the quote shows how easy it is to underestimate the power of a subscription model and the network effects when companies operate with few tangible assets (retail stores), and your main product is electronic information or “content”. Less obvious is how Netflix has continued to thrive despite the threat from Amazon, which was apparent even in 2005.

Many other companies have jumped on the bandwagon. In some cases it’s valid: Visa Inc presentations clearly imply they should be valued more like a technology company (which often trade on huge multiples of tangible book value) than a bank (which still trade on discounts to book). Visa was originally owned by its member banks, before they listed it on the NYSE in early 2008, it’s increased in value by 10x since then. YouGov which I covered a week ago, call themselves “a platform” on the front page of their investor presentation and has also ten bagged in the last 5 years.

But we need to be wary of fads, not all those claiming to be surfing the latest wave on a platform will enjoy the ride. Many crowd funding platforms don’t enjoy network effects (eg LendingClub, Funding Circle and Zopa). Traditional banks (whose balance sheets dwarf the new entrants) report margins so low that it is doubtful that new entrant “marketplace lenders” enjoy any benefit from lenders and borrowers transacting in the same place on their new platforms.

Given that most UK companies don’t report quarterly results, mid October is rather quiet for company news. I’m going to try to draw out a couple of themes, one is the subscription model (Amazon Prime, Netflix) and also exchanges where customers own the marketplace.

Aquis Exchange

Aquis Exchange H1 presentation caught my eye on www.piworld.co.uk

Exchanges like the London Stock Exchange are natural monopolies, for most of their history they have been mutually owned by their own customers. Rather than regulation, the most convenient way to prevent price gouging by natural monopolies like stock exchanges, is for the customers to also be the owners. However, as big banks became more involved in stock exchanges, the interests of owners diverged, between big banks (favouring institutional clients and large orders) and smaller brokers (retail order flow).

The Stockholm exchange in Sweden was the first exchange to demutualise in 1993, and London Stock Exchange followed suit in July 2001, listing its shares on its own market. According to Marc Rubinstein, who publishes the https://netinterest.substack.com/ newsletter, not one of the world’s major exchanges is now structured as a mutual, and nearly three quarters are publicly traded. The share prices tell an interesting story: London Stock Exchange IPO’ed at below £3 and is worth around £90 per share now. Compare that to UK bank shares, which have been dire, falling between 50-100% over the same time period, and even that abysmal performance was achieved with rescue capital increases, plus Government and Central Bank support!

Around the same time as stock exchanges demutualised and became more profit focused, regulation encouraged competition. This allowed trades to be executed in new venues with names like BATS, Turquoise and Chi X. The latter was sold to the former, while the LSE bought Turquoise. The market is still consolidating BATS itself was bought by CBOE (Chicago Board of Exchange) and the Stockholm Exchange was eventually bought by Nasdaq.

Hence my interest in Aquis Exchange, which was founded by the former CEO of Chi-X Europe (Alasdair Haynes) after Chi X was sold to BATS in late 2011. Aquis is a cash equities trading venue for European shares, offering more than 1,500 stocks and ETFs across 14 European markets, with a unique subscription based pricing model. Management point to Netflix, Spotify and Amazon Prime, as examples of successful subscription models, where a monthly fee gives you access to huge amounts of content. Similarly, Aquis does not charge a percentage of the value of each stock that a customer trades, the highest tier of membership offers customers unlimited trading and data, instead customers pay for message traffic. This struck me as an interesting model, after something that Jeff Sprecher, the CEO of ICE, which owns the New York Stock Exchange, said:

“I believe that execution is not particularly valuable… I think over time finding a buyer and a seller in a world where we have the Internet is really the most simple thing in the world, and networks can form up overnight to find buyers and sellers… And it was helpful to buy the New York Stock Exchange, because I think the New York Stock Exchange essentially is at zero. We don’t run it that way because it’s a whole big business. We don’t break out execution, but I don’t think there’s any money – I mean, we may lose money on execution if we were to really allocate cost. And how do we make the money? Data, listings, connectivity, information, catering, we print banners, I mean, everything around the execution is where we make money. And so that helped inform us that execution is probably in a digital world is going to go to zero.”*

Aquis management seem to be thinking along the same lines. Like Netflix or Spotify, they are a subscription service, which encourages customers to increase their use of the product because there is no marginal cost increase as customers increase. As more subscribers sign up, Netflix sees more revenues, which it invests in its product, which improves as more people sign up.

Similarly the key to a successful exchange is network effects, buyers want to transact where sellers are and vice versa. Companies want to list where there is both retail and institutional capital – and if you can get things right, you have a wonderful business with high returns and barriers to entry. So it is no coincidence that subscription model and network effects go hand in hand.

In March 2020 Acquis completed the acquisition of loss making NEX for £1 from CME Group. This was formerly known as PLUS Markets or OFEX, and consists of illiquid companies (ironically many of them brewers or vineyards) like Adnams and Chapel Down.

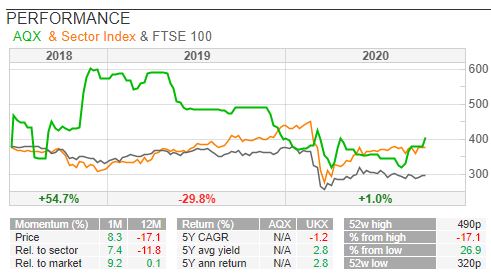

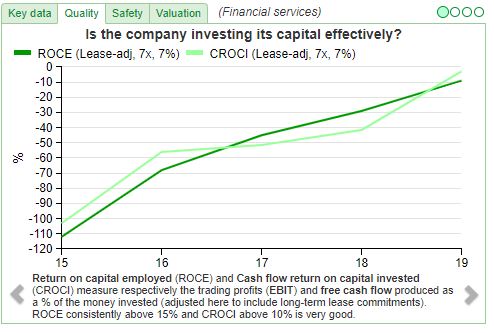

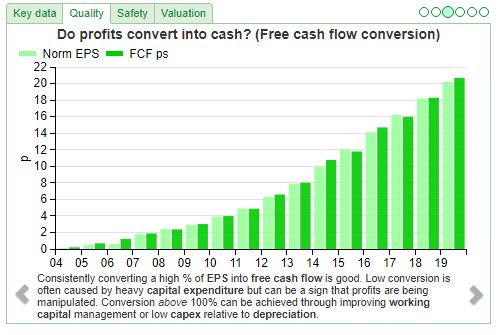

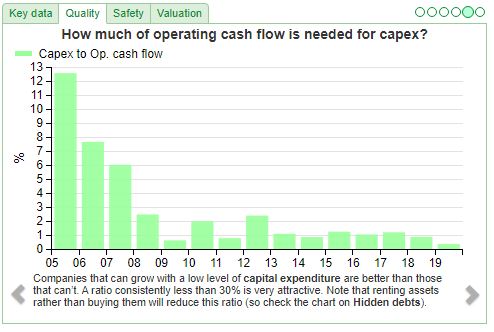

Aquis shares are expensive (market cap £110 v £4.9m revenue H1 2020), and the company is making just £12K profit in the first 6 months of the year, despite very favourable conditions (lots of trading and volatility). However, revenue increased 42% year on year, and market share of trading is 4.51% so if they can persuade more customers to transact on their platform this could be very interesting. Profitability measures are clearly moving in the right direction as market share increases.

Even if investors are put off by the high valuation, Haynes talks about reducing bid offer spreads in smaller companies which is clearly a benefit to most of us who tend to focus on smaller sized, less followed companies. The emphasis on best execution also seems likely to benefit from MIFID II regulations. The company says it is fully prepared for a no deal BREXIT, with functional legal entities set up within the EU.

One way for Aquis to increase their probability of success would be for management to encourage small cap institutional fund managers to become owners – a form of listed mutual. Interestingly Invesco own 6.7%, Canaccord Wealth Management 5.9%, Kendall 5%, Miton 4.4%, Rathbones 3.2% and Schroders 3%. Other notable shareholders are XTX Markets 9.6%, and Rich Ricci the scion of Bob Diamond at Barclays Capital, who owns 7.9%. I don’t own shares, psychologically I find it hard to pay 10x revenue, but Aquis is certainly on my watch list.

From Rightmove to OnTheMarket

Aside from the London Stock Exchange, another example of an exchange, originally owned by its users, that has done spectacularly well is Rightmove. This was started in 2000 by the four largest estate agencies at the time: Countrywide, Connells, Halifax and RSA. To encourage estate agents to post properties, the website was initially free to list with charging introduced later.

“Investing” in price reductions or even free product for customers make sense if there are network effects. The fund manager Nicholas Sleep** was one of the first to grasp this. Sacrificing short-term profits would strengthen what he referred to as the “digital moats” of internet businesses. Superficial analysis suggests Netflix had been selling its product too cheaply to customers, but “digital moats” thinking justifies growing customer numbers at the expense of short term reported profits or RoCE. It also explains why Netflix has continued to thrive despite Amazon encroaching on its territory.

And this is what seems to have happened with Rightmove. Once the virtuous circle was established, the original owners decided to float the business on the stock market in 2006 at £3.35 a share. Adjusted for a stock split it is now up 20x.

Rightmove likes to say it doesn’t compete with estate agents, they are customers who list properties on the website. Instead it competes against (and has largely benefitted from the demise of) local newspapers, where properties used to be advertised before the internet adoption became widespread. This is true to some extent, but clearly with Returns on Capital of 513% v persistently loss making Countrywide and Foxtons, Rightmove enjoys being the most precious link in the value chain.

So in 2013, history repeated itself and several estate agents decided to create a new residential property website as a challenger to Rightmove. Unsurprisingly this found support among estate agents across the UK. The portal launched in January 2015 with the properties of 4,600 branches. The new portal, called OnTheMarket plc was listed on AIM in February 2018. This raised £30 million of new equity capital, valuing it at £100m, but with 70% of the share capital still owned by estate agents. By this year, estate agent ownership had fallen to 65%. Shareholders seem happy for the business to operate at a loss, in order to build market share against the dominant player (Rightmove).

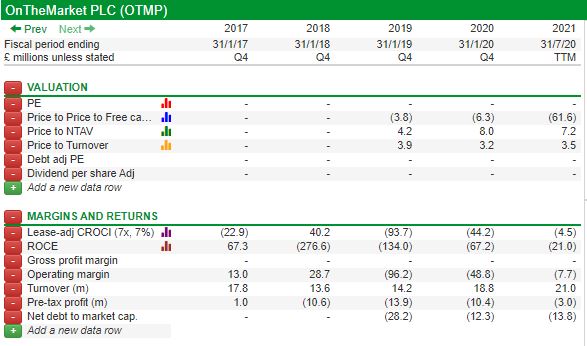

It is not clear to me that OnTheMarket can successfully compete against Rightmove’s established “digital moat”. Rightmove has become well established in home buyer’s mind as the website to search for properties. I will watch with interest the improving profitability and growing revenue, shown on the next page.

OnTheMarket H1 to 31 July 2020

OnTheMarket reported group revenue up 28% to £10.2m for the first 6 months to 31 July. The company, which has been loss making, managed to report a profit of £700K for the same time period. This was helped by a savage reduction in marketing costs down by 2/3 to £2.2m. Net cash stood at £9.8m at the end of July, which grew to £10.3m by the end of this September.

The Group announced in March the Chief Executive Ian Springett would leave, and in September they appointed Jason Tebb as his successor, who starts in December. Given the new management, the outlook statement probably should be treated with some caution, but has suggested that the Group expects to broadly breakeven adjusted operating profit position for the full financial year, which implies a small second half loss.

Demutualisation and moats

So investing is easy? Let’s just find companies which used to be owned by their customers like Visa, Rightmove and the London Stock Exchange, and when they become public companies: buy!

Sadly not. Simply being owned by your customers is not enough to guarantee success. In 1998 the combined market capitalisation of the five demutualised UK building societies was £51.3bn, and they made aggregate pre-tax profits of £4.15bn.*** All of these former mutuals failed spectacularly within a decade. The reason is that none of these lenders enjoyed network effects, Northern Rock’s cost income ratio was lower than Halifax, despite Halifax having 7x larger mortgage book at the time of demutualisation. Both had lower cost income ratios than HSBC, though (or perhaps because) “the World’s Local Bank” had operations sprawling across the globe. The internet economy was supposed to be bad news for banks because they had legacy IT and fixed cost infrastructure like branches. In reality the internet was bad news for banks, because they were distributing a commodity product and had no moat, so the dumbest competitors (Northern Rock and HBOS) destroyed lending margins in the sector.

Mutually owned monopolies v competition

Monopolies are bad news for customer service, and economists have tended to assume the best way of dealing with this is competition. I’m sceptical, partly because the 2008 financial crisis showed that economists understood neither the banking system nor financial markets. Competition doesn’t seem to have prevented a 20x rise in the LSE share price. And the monopoly like returns has been accompanied by customer dissatisfaction among retail investors: see tweet from Rhomboid below.

More sinister is the story of ENRC, as told by Tom Burgis.**** The LSE seems content to allow extractive industries from dubious parts of the world, with poor corporate governance to list on their exchange. This is short term profit maximisation at the expense of the long term “moat” of the business, in my view. One approach for the disgruntled, may be to buy shares in the LSE, and use that ownership to try to hold management to account at the AGM. This would be a return to the days when stock exchanges were less profit focused, but better served customers.

A second related thought is that Government has been keen to increase competition in banking, despite shareholders having suffered a terrible couple of decades. My analysis suggests bank management have become too obsessed with fads like network effects and “winner takes almost all” economics. Northern Rock claimed to have a virtuous circle strategy of higher market share leading to low cost loans. HBOS claimed to be following the Asda/Walmart model. When the UK Government demanded Stephen Hester shrink Royal Bank’s investment banking division, he is said to have replied “You can’t be half pregnant.”

Unlike shareholders in the LSE, bank shareholders should follow the example of the UK Government, and be pressuring management to forget about market share, network externalities, chasing new business etc which simply don’t apply to lending money in the same way that they do for stock exchanges. Bank shareholders have been ill served by an oversupply of cheap credit in the last two decades, and they should be pressuring management to redress the balance, in favour of profitable lending.

We shall see.

Bruce Packard

*thanks to Marc Rubinstein for pulling out this quote.

** I’d never heard of Nicholas Sleep before I read this FT piece on him. https://on.ft.com/3ifQ81s

He has achieved a cult-like status among younger fund managers, who have searched out rare and highly prized copies of his old investment letters. Such is his air of mystery that some have even jokingly referred to him as the “Keyser Söze of investing”, in reference to the enigmatic character in The Usual Suspects.

*** £51.3bn may seem curiously specific. That’s because I still have an old Credit Suisse First Boston equity research report from 1998, on the outlook for the mortgage banks (Alliance & Leicester, Abbey National, Halifax, Northern Rock, Woolwich). You may be wondering why Bradford and Bingley is not included. They only listed on the Stock Exchange in 2000.

****Kleptopia: How Dirty Money is Conquering the World by Tom Burgis https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0008308349/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_x_LXXHFbHVCHPMK

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Weekly Commentary: 19/10/20 – On network effects and fads

“Fad companies are companies with good business models or good products. So, why would we be interested in shorting a company that has a good product? Because of the threat it presents to others and their likely response to that threat. For example, Netflix had a terrific idea of renting DVDs through the mail, which was much more efficient but obviously a terrific threat to Blockbuster. One had to anticipate that Blockbuster would respond. Amazon, which has the capability of this kind of product, also entered the business. So, what was once a good business model changed.”

David Rocker CFA Conference Proceedings 2005.

We are coming into Q3 reporting season for US technology stocks. Given that expectations are so high, it’s tempting to believe that high returns are not sustainable. The above quote from a short seller 15 years ago, shows that may be a mistake. It’s now clear that Netflix enjoyed a structurally lower cost base (no video stores), and however Blockbuster responded they were likely to lose. I think the quote shows how easy it is to underestimate the power of a subscription model and the network effects when companies operate with few tangible assets (retail stores), and your main product is electronic information or “content”. Less obvious is how Netflix has continued to thrive despite the threat from Amazon, which was apparent even in 2005.

Many other companies have jumped on the bandwagon. In some cases it’s valid: Visa Inc presentations clearly imply they should be valued more like a technology company (which often trade on huge multiples of tangible book value) than a bank (which still trade on discounts to book). Visa was originally owned by its member banks, before they listed it on the NYSE in early 2008, it’s increased in value by 10x since then. YouGov which I covered a week ago, call themselves “a platform” on the front page of their investor presentation and has also ten bagged in the last 5 years.

But we need to be wary of fads, not all those claiming to be surfing the latest wave on a platform will enjoy the ride. Many crowd funding platforms don’t enjoy network effects (eg LendingClub, Funding Circle and Zopa). Traditional banks (whose balance sheets dwarf the new entrants) report margins so low that it is doubtful that new entrant “marketplace lenders” enjoy any benefit from lenders and borrowers transacting in the same place on their new platforms.

Given that most UK companies don’t report quarterly results, mid October is rather quiet for company news. I’m going to try to draw out a couple of themes, one is the subscription model (Amazon Prime, Netflix) and also exchanges where customers own the marketplace.

Aquis Exchange

Aquis Exchange H1 presentation caught my eye on www.piworld.co.uk

Exchanges like the London Stock Exchange are natural monopolies, for most of their history they have been mutually owned by their own customers. Rather than regulation, the most convenient way to prevent price gouging by natural monopolies like stock exchanges, is for the customers to also be the owners. However, as big banks became more involved in stock exchanges, the interests of owners diverged, between big banks (favouring institutional clients and large orders) and smaller brokers (retail order flow).

The Stockholm exchange in Sweden was the first exchange to demutualise in 1993, and London Stock Exchange followed suit in July 2001, listing its shares on its own market. According to Marc Rubinstein, who publishes the https://netinterest.substack.com/ newsletter, not one of the world’s major exchanges is now structured as a mutual, and nearly three quarters are publicly traded. The share prices tell an interesting story: London Stock Exchange IPO’ed at below £3 and is worth around £90 per share now. Compare that to UK bank shares, which have been dire, falling between 50-100% over the same time period, and even that abysmal performance was achieved with rescue capital increases, plus Government and Central Bank support!

Around the same time as stock exchanges demutualised and became more profit focused, regulation encouraged competition. This allowed trades to be executed in new venues with names like BATS, Turquoise and Chi X. The latter was sold to the former, while the LSE bought Turquoise. The market is still consolidating BATS itself was bought by CBOE (Chicago Board of Exchange) and the Stockholm Exchange was eventually bought by Nasdaq.

Hence my interest in Aquis Exchange, which was founded by the former CEO of Chi-X Europe (Alasdair Haynes) after Chi X was sold to BATS in late 2011. Aquis is a cash equities trading venue for European shares, offering more than 1,500 stocks and ETFs across 14 European markets, with a unique subscription based pricing model. Management point to Netflix, Spotify and Amazon Prime, as examples of successful subscription models, where a monthly fee gives you access to huge amounts of content. Similarly, Aquis does not charge a percentage of the value of each stock that a customer trades, the highest tier of membership offers customers unlimited trading and data, instead customers pay for message traffic. This struck me as an interesting model, after something that Jeff Sprecher, the CEO of ICE, which owns the New York Stock Exchange, said:

“I believe that execution is not particularly valuable… I think over time finding a buyer and a seller in a world where we have the Internet is really the most simple thing in the world, and networks can form up overnight to find buyers and sellers… And it was helpful to buy the New York Stock Exchange, because I think the New York Stock Exchange essentially is at zero. We don’t run it that way because it’s a whole big business. We don’t break out execution, but I don’t think there’s any money – I mean, we may lose money on execution if we were to really allocate cost. And how do we make the money? Data, listings, connectivity, information, catering, we print banners, I mean, everything around the execution is where we make money. And so that helped inform us that execution is probably in a digital world is going to go to zero.”*

Aquis management seem to be thinking along the same lines. Like Netflix or Spotify, they are a subscription service, which encourages customers to increase their use of the product because there is no marginal cost increase as customers increase. As more subscribers sign up, Netflix sees more revenues, which it invests in its product, which improves as more people sign up.

Similarly the key to a successful exchange is network effects, buyers want to transact where sellers are and vice versa. Companies want to list where there is both retail and institutional capital – and if you can get things right, you have a wonderful business with high returns and barriers to entry. So it is no coincidence that subscription model and network effects go hand in hand.

In March 2020 Acquis completed the acquisition of loss making NEX for £1 from CME Group. This was formerly known as PLUS Markets or OFEX, and consists of illiquid companies (ironically many of them brewers or vineyards) like Adnams and Chapel Down.

Aquis shares are expensive (market cap £110 v £4.9m revenue H1 2020), and the company is making just £12K profit in the first 6 months of the year, despite very favourable conditions (lots of trading and volatility). However, revenue increased 42% year on year, and market share of trading is 4.51% so if they can persuade more customers to transact on their platform this could be very interesting. Profitability measures are clearly moving in the right direction as market share increases.

Even if investors are put off by the high valuation, Haynes talks about reducing bid offer spreads in smaller companies which is clearly a benefit to most of us who tend to focus on smaller sized, less followed companies. The emphasis on best execution also seems likely to benefit from MIFID II regulations. The company says it is fully prepared for a no deal BREXIT, with functional legal entities set up within the EU.

One way for Aquis to increase their probability of success would be for management to encourage small cap institutional fund managers to become owners – a form of listed mutual. Interestingly Invesco own 6.7%, Canaccord Wealth Management 5.9%, Kendall 5%, Miton 4.4%, Rathbones 3.2% and Schroders 3%. Other notable shareholders are XTX Markets 9.6%, and Rich Ricci the scion of Bob Diamond at Barclays Capital, who owns 7.9%. I don’t own shares, psychologically I find it hard to pay 10x revenue, but Aquis is certainly on my watch list.

From Rightmove to OnTheMarket

Aside from the London Stock Exchange, another example of an exchange, originally owned by its users, that has done spectacularly well is Rightmove. This was started in 2000 by the four largest estate agencies at the time: Countrywide, Connells, Halifax and RSA. To encourage estate agents to post properties, the website was initially free to list with charging introduced later.

“Investing” in price reductions or even free product for customers make sense if there are network effects. The fund manager Nicholas Sleep** was one of the first to grasp this. Sacrificing short-term profits would strengthen what he referred to as the “digital moats” of internet businesses. Superficial analysis suggests Netflix had been selling its product too cheaply to customers, but “digital moats” thinking justifies growing customer numbers at the expense of short term reported profits or RoCE. It also explains why Netflix has continued to thrive despite Amazon encroaching on its territory.

And this is what seems to have happened with Rightmove. Once the virtuous circle was established, the original owners decided to float the business on the stock market in 2006 at £3.35 a share. Adjusted for a stock split it is now up 20x.

Rightmove likes to say it doesn’t compete with estate agents, they are customers who list properties on the website. Instead it competes against (and has largely benefitted from the demise of) local newspapers, where properties used to be advertised before the internet adoption became widespread. This is true to some extent, but clearly with Returns on Capital of 513% v persistently loss making Countrywide and Foxtons, Rightmove enjoys being the most precious link in the value chain.

So in 2013, history repeated itself and several estate agents decided to create a new residential property website as a challenger to Rightmove. Unsurprisingly this found support among estate agents across the UK. The portal launched in January 2015 with the properties of 4,600 branches. The new portal, called OnTheMarket plc was listed on AIM in February 2018. This raised £30 million of new equity capital, valuing it at £100m, but with 70% of the share capital still owned by estate agents. By this year, estate agent ownership had fallen to 65%. Shareholders seem happy for the business to operate at a loss, in order to build market share against the dominant player (Rightmove).

It is not clear to me that OnTheMarket can successfully compete against Rightmove’s established “digital moat”. Rightmove has become well established in home buyer’s mind as the website to search for properties. I will watch with interest the improving profitability and growing revenue, shown on the next page.

OnTheMarket H1 to 31 July 2020

OnTheMarket reported group revenue up 28% to £10.2m for the first 6 months to 31 July. The company, which has been loss making, managed to report a profit of £700K for the same time period. This was helped by a savage reduction in marketing costs down by 2/3 to £2.2m. Net cash stood at £9.8m at the end of July, which grew to £10.3m by the end of this September.

The Group announced in March the Chief Executive Ian Springett would leave, and in September they appointed Jason Tebb as his successor, who starts in December. Given the new management, the outlook statement probably should be treated with some caution, but has suggested that the Group expects to broadly breakeven adjusted operating profit position for the full financial year, which implies a small second half loss.

Demutualisation and moats

So investing is easy? Let’s just find companies which used to be owned by their customers like Visa, Rightmove and the London Stock Exchange, and when they become public companies: buy!

Sadly not. Simply being owned by your customers is not enough to guarantee success. In 1998 the combined market capitalisation of the five demutualised UK building societies was £51.3bn, and they made aggregate pre-tax profits of £4.15bn.*** All of these former mutuals failed spectacularly within a decade. The reason is that none of these lenders enjoyed network effects, Northern Rock’s cost income ratio was lower than Halifax, despite Halifax having 7x larger mortgage book at the time of demutualisation. Both had lower cost income ratios than HSBC, though (or perhaps because) “the World’s Local Bank” had operations sprawling across the globe. The internet economy was supposed to be bad news for banks because they had legacy IT and fixed cost infrastructure like branches. In reality the internet was bad news for banks, because they were distributing a commodity product and had no moat, so the dumbest competitors (Northern Rock and HBOS) destroyed lending margins in the sector.

Mutually owned monopolies v competition

Monopolies are bad news for customer service, and economists have tended to assume the best way of dealing with this is competition. I’m sceptical, partly because the 2008 financial crisis showed that economists understood neither the banking system nor financial markets. Competition doesn’t seem to have prevented a 20x rise in the LSE share price. And the monopoly like returns has been accompanied by customer dissatisfaction among retail investors: see tweet from Rhomboid below.

More sinister is the story of ENRC, as told by Tom Burgis.**** The LSE seems content to allow extractive industries from dubious parts of the world, with poor corporate governance to list on their exchange. This is short term profit maximisation at the expense of the long term “moat” of the business, in my view. One approach for the disgruntled, may be to buy shares in the LSE, and use that ownership to try to hold management to account at the AGM. This would be a return to the days when stock exchanges were less profit focused, but better served customers.

A second related thought is that Government has been keen to increase competition in banking, despite shareholders having suffered a terrible couple of decades. My analysis suggests bank management have become too obsessed with fads like network effects and “winner takes almost all” economics. Northern Rock claimed to have a virtuous circle strategy of higher market share leading to low cost loans. HBOS claimed to be following the Asda/Walmart model. When the UK Government demanded Stephen Hester shrink Royal Bank’s investment banking division, he is said to have replied “You can’t be half pregnant.”

Unlike shareholders in the LSE, bank shareholders should follow the example of the UK Government, and be pressuring management to forget about market share, network externalities, chasing new business etc which simply don’t apply to lending money in the same way that they do for stock exchanges. Bank shareholders have been ill served by an oversupply of cheap credit in the last two decades, and they should be pressuring management to redress the balance, in favour of profitable lending.

We shall see.

Bruce Packard

*thanks to Marc Rubinstein for pulling out this quote.

** I’d never heard of Nicholas Sleep before I read this FT piece on him. https://on.ft.com/3ifQ81s

He has achieved a cult-like status among younger fund managers, who have searched out rare and highly prized copies of his old investment letters. Such is his air of mystery that some have even jokingly referred to him as the “Keyser Söze of investing”, in reference to the enigmatic character in The Usual Suspects.

*** £51.3bn may seem curiously specific. That’s because I still have an old Credit Suisse First Boston equity research report from 1998, on the outlook for the mortgage banks (Alliance & Leicester, Abbey National, Halifax, Northern Rock, Woolwich). You may be wondering why Bradford and Bingley is not included. They only listed on the Stock Exchange in 2000.

****Kleptopia: How Dirty Money is Conquering the World by Tom Burgis https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/0008308349/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_x_LXXHFbHVCHPMK

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.