How we measure return on capital depends on what we want to know: whether a company is good at making profit from its operations, or whether it is good at buying other businesses.

As I write, the stockmarket is crashing. I have invested in strong businesses that should prosper through thick and thin, but that strategy is being put to the test now. Being tested is unnerving, but it is behind a long list of worries, some more rational than others, about relatives, friends, cancelling events, and whether I am a complete dimwit for not stockpiling toilet paper and paracetamol while the shops had them.

If you are finding it hard to focus you have my sympathy. So am I! That’s why I’m grateful to a reader of my last article on finding companies that generate repeat business like Fundsmith Equity fund does. He sent me a very interesting problem, and it’s a great relief to be thinking about a problem I can resolve, while so much is going on that is uncertain and worrisome:

I would just like to ask your views on one point: in the article you mention that Terry Smith excludes goodwill in his CROCI calculation. You may be aware that [another financial writer] has written on this topic and suggested that one should not exclude goodwill on the basis that most goodwill represents the premium over asset value from an acquisition and that the company’s capital has very much been used to make that acquisition.

Like so many good questions, the answer is a can of worms. Before I open it, some clarifications:

- Terry Smith is the fund manager of Fundsmith Equity

- CROCI stands for Cash Return on Capital Invested, a measure of return on capital

- Fundsmith doesn’t say it excludes goodwill in its return on capital calculations but it probably does because it focuses on return on operating capital. Goodwill is generated from acquisitions, not operations

- This article is not a critique of the article referred to in my correspondent’s question. The information about it included in the question is correct. Buying goodwill is a use of a firm’s capital!

Despite this, my default measure of profitability ignores goodwill and other intangible assets that, like goodwill, are only created as a result of an acquisition. But for highly acquisitive companies I also keep my eye on a second version of CROCI that does account for these things, but not in the standard way. Let me explain!

A thought experiment

Imagine two companies that are similar in almost every way. Company A has grown entirely under its own steam. It does something in a very special way that few other businesses do. A lot of its value is tied up in the way it does this, intangible things related to the knowledge of its staff, the way they operate, and the relationships between the company and customers, suppliers and so on. The value of these assets is not recognised on the balance sheet like equipment and buildings because it has been treated as a cost rather than an investment. The company may have spent millions on research, training, schmoozing customers, and advertising but that money has gone. Its legacy is the high return on capital the company earns and the unaccounted for ‘goodwill’ it has created. The return on capital is high because the denominator of the calculation does not include the value of the intangible assets the company has created. Even if accountants wanted to value them, how could they with any certainty?

Company B is just like Company A. The only significant difference in this thought experiment is that it didn’t create the similar assets that earn the similar returns, it bought them when it acquired company C. At the time company B bought Company C, both companies knew that company C did something valuable, far more valuable than the value of the tangible assets (the materials, equipment, and buildings) required to operate the business, so company B agreed to pay much more than the value of these tangible assets. Suddenly the intangible assets have a value, it’s however much the bosses of Company B decided to pay. This is goodwill and other acquisition related intangible assets, and it is recorded as assets on Company B’s balance sheet.

Company A and Company B earn similar profits (returns) for a similar activity, but Company B has much more capital on its balance sheet because it’s goodwill is accounted for, and that means company B’s return on capital will be much lower than company A’s. How can that be? We have just said they are similar companies. If we’re not careful we could end up paying a lot more for company A even though its higher return on capital is an accounting figment.

Cash return on operating capital

The difference is not in what they do, but how they got to this point, which is a historical footnote. The difference in their balance sheets is a result of the different way accountants treat acquired intangible assets from assets a company develops itself.

Return on capital is a measure of how efficiently a company turns investment (capital) into profit (return). If we are to compare how well companies are likely to do this in future, we need to exclude goodwill, because goodwill is a sunk cost. Companies do not create more goodwill, in accounting terms, from their current operations.

We will call this ratio Cash return on operating capital.

Cash return on total invested capital

If a business is not particularly acquisitive, or has been but is operating a different strategy now, goodwill may not be very relevant. But some companies make acquisitions their central strategic goal, and we need to form a view on whether they have been good acquirers, which may give us confidence they will continue to be. To do that we need to factor goodwill into the equation.

But the amount a company has actually spent on goodwill is not necessarily the value of goodwill on its balance sheet. Sometimes companies write off goodwill because they no longer believe it is as valuable as they thought when they acquired it. If they have made mistakes though, that should count against them. We need the value of goodwill at cost, which is usually itemised in the notes to the accounts. We might call this ratio Cash return on total capital invested.

Judges Scientific

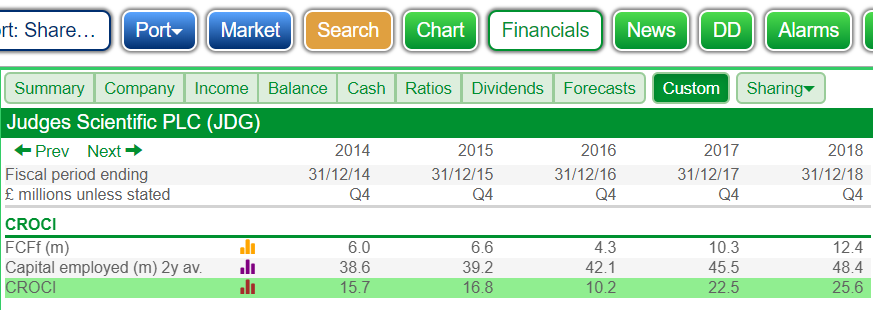

To show you the difference between the two versions of CROCI, I will use a highly acquisitive company, one of those where goodwill is significant. This is a custom table created in SharePad showing how CROCI is calculated in the case of scientific instrument manufacturer Judges Scientific. CROCI is Free cash flow for the firm as a percentage of average capital employed (the average of the most recent year and the previous year, including goodwill):

NB: You can create custom tables in the green Financials section of SharePad

For example, in 2018 Judges Scientific earned £12.4m of Free cash flow for the firm and its capital employed was £48.4m, so FCFf was 25.6% of capital employed.

Judges Scientific’s strategy is to buy businesses that earn high and sustainable returns, use those returns to pay off any debt used in the acquisition, and then, buy more businesses. It has been collecting businesses for two decades.

Before I calculate a Cash return on operating capital and Cash return on total capital invested, though, I must talk more about other acquisition related intangible assets.

Sometimes companies recognise other intangible assets, like brands and customer relationships, when they acquire a business. We need to treat them the same way as we treat goodwill. But there’s a problem. Some intangible assets are created in the normal run of business, when a company buys software for example. We cannot just assume all intangible assets are related to acquisitions. Where companies have a mixture of acquisition-related intangibles and internally generated intangibles we must try to work out which are which from the note on intangible assets in the company’s accounts, and only exclude acquisition related intangibles in our calculations. IAS 38, an accounting standard, provides more guidance on which intangible assets a company can create internally, and which can only be created by a ‘business combination’.

To keep things simple, I chose Judges Scientific because all of its intangible assets are created by acquisition.

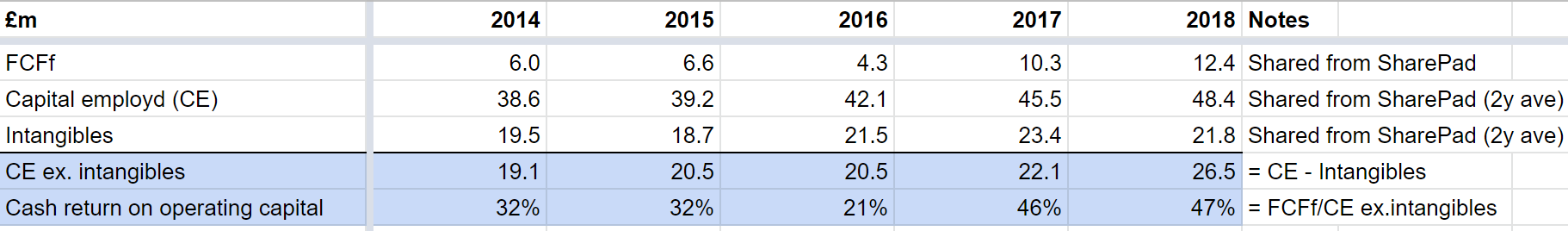

To calculate Cash return on operating capital all we need to do is deduct the value of intangible assets from capital employed, and recalculate the ratio. I used Sharepad’s sharing feature to export the first three lines of raw data in this spreadsheet and did the calculations in the fourth and fifth lines:

The result gives me a warm fuzzy feeling inside. Even in its worst year, 2016, Judges Scientific’s businesses were very profitable in aggregate (the range is 21% to 47%). These businesses are very good at converting investment in tangible assets into cash (their Return on operating capital is high). If Judges Scientific were to make no more acquisitions, it would be a high quality gaggle of businesses.

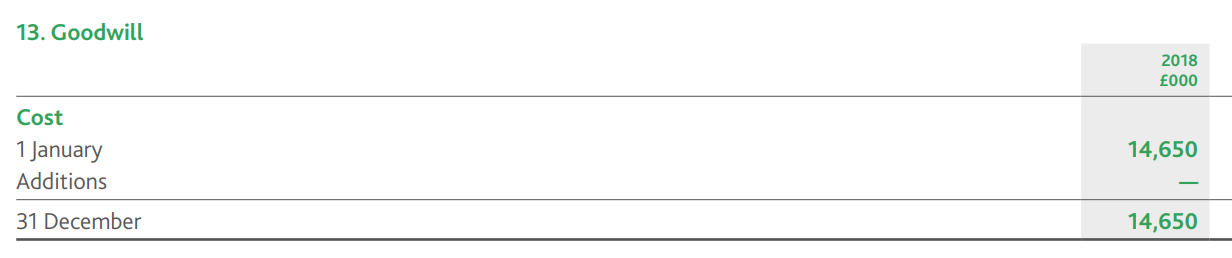

But it plans to make more acquisitions so we need to look at this aspect of the business. Here I am afraid I must expose you to the notes in Judges’ accounts. The note for goodwill contains good news:

Source: Judges Scientific annual report (2018)

There are no write-offs. The cost value of Judges Scientific’s goodwill on 31 Dec 2018 (its latest published results) was the same as its book value. This on its own is a sign the company is a good acquirer.

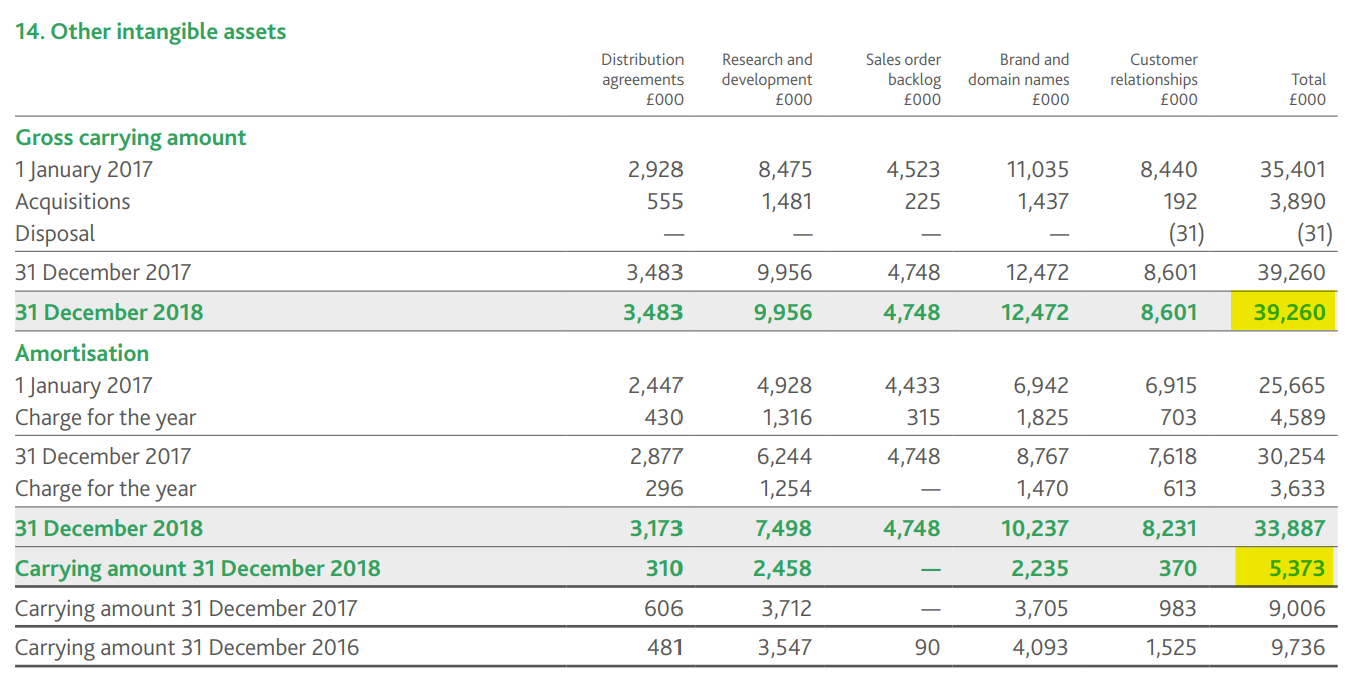

Other intangible assets, though, are deemed to have useful lives like physical assets, and they are written-off, or amortised, over time just like machines are depreciated. Their cost values (gross carrying amount, below), therefore, are higher than their book values (carrying amount, below):

Source: Judges Scientific annual report (2018)

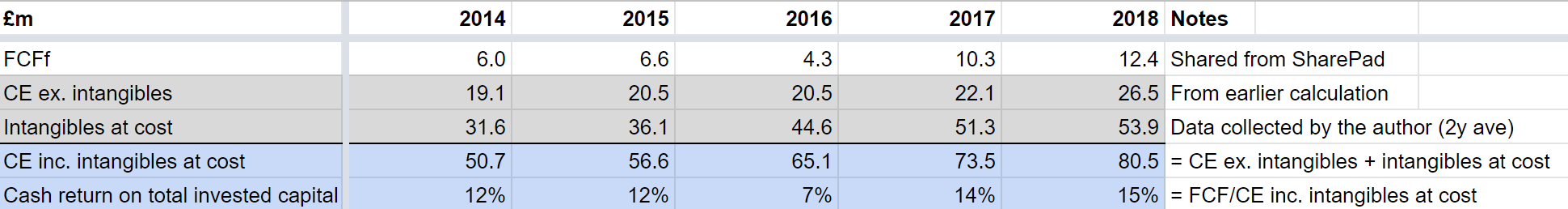

To calculate Cash return on total invested capital, we can remove the book value of intangible assets from SharePad’s calculation of Capital employed and replace it with the cost value (of goodwill plus intangible assets averaged over the year in question and the previous year*). Then we recalculate the ratio:

As you’d expect, because we’ve inflated the denominator of the calculation, Cash return on total invested capital is lower than the standard CROCI measure and much lower than Cash return on operating capital.

The 10% rule

Generally, I start to ask questions if returns fall below 10%, as they did at Judges Scientific in 2016 when Cash return on total invested capital was 7%, but we have to be careful not to jump to conclusions. Cash flows can be volatile, and the odd sub-par year is not problematic as long as there are lots of above-par years. In 2015, the company made a big acquisition and in 2016 it made four smaller ones, a period of higher than usual activity that lifted intangible assets at cost substantially and depressed Cash return on total capital employed. Acquisitions temporarily depress the figure because the company bears the full cost of the acquisition immediately, but if it buys good businesses, it expects growing returns for many years.

These ratios reinforce my view that Judges Scientific owns highly profitable businesses and earns decent returns on the money it has invested in them. The return on operating capital gives me a better idea of just how good these businesses are than the standard ratio, and the return on total invested capital figure is a stricter test of whether the company is good at acquisitions.

Phew!

*If you would like to explore the spreadsheet I used to collect data from SharePad and the Judges Scientific annual reports, It’s here. Although you cannot edit my version, you can, if you have a Google account, make a copy and play with it. The first tab contains the CROCI calculations described above. The second tab contains the calculation of Judges Scientific’s intangible assets at cost.

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.