Richard investigates Dialight, a supplier of industrial LED lighting that flared up ten years ago briefly setting the stock market alight, and subsequently dimmed alarmingly. What are its prospects now it is taking back control of manufacturing?

Ten years ago Dialight was a feted, fast growing business in a booming industry, LED lighting, but it failed to deliver on the promise.

Like many investors I considered buying shares while Dialight looked like a good business early in the 2010s, but eventually I settled on another lighting firm, FW Thorpe, and pretty much lost interest in Dialight because by then it was turning into something of a horror-show.

As you can see from the chart, over the past ten years shares in FW Thorpe (pink line) have risen 550%, although the peak was after seven years when the shares had risen 650%. Dialight grew much faster (black line). It hit the 550% mark in little more than three years, but today the share price is back where it started. Dialight doesn’t currently pay a dividend either.

Although these two companies are far from analogous, there are lessons to be learned from their experience.

A growth company in its pomp

In June 2013, when Dialight was in its pomp, an industry report expected the company to perform better than many of its peers, correctly noting that the long lifespan of LEDs and the increasing capabilities of the lighting systems incorporating them was shifting value (and therefore profit) away from the bulbs and into fixtures containing optics and controls necessary to manage increasingly sophisticated products. Dialight makes lighting fixtures incorporating LEDs for heavy industry where the longer lifespan of LED lighting was especially attractive because of the cost of replacing faulty traditional lamps, more susceptible to extreme heat and vibration. Then, as now, Dialight claimed to be the world leader in this niche, a niche that looked eminently defendable. What is more, Dialight was an LED company to the core. It had not made its name in lighting and in 2013, its biggest business was Signals: LED beacons on mobile ‘phone masts, and the lights in traffic lights for example, a profitable but more mature business. As a specialist, it had stolen a march on traditional lighting companies.

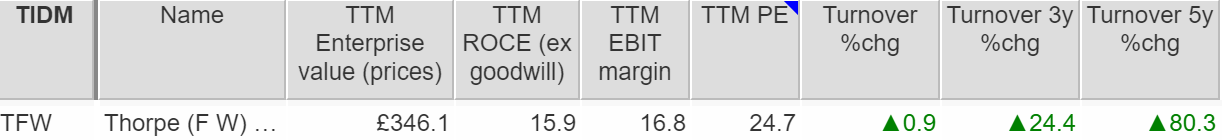

A head start, specialist expertise, leadership in a niche market, it is hardly surprising investors got carried away. The numbers looked good too (apart from the high PE). It was earning a 25% return on capital and revenue had grown 69% over the previous five years:

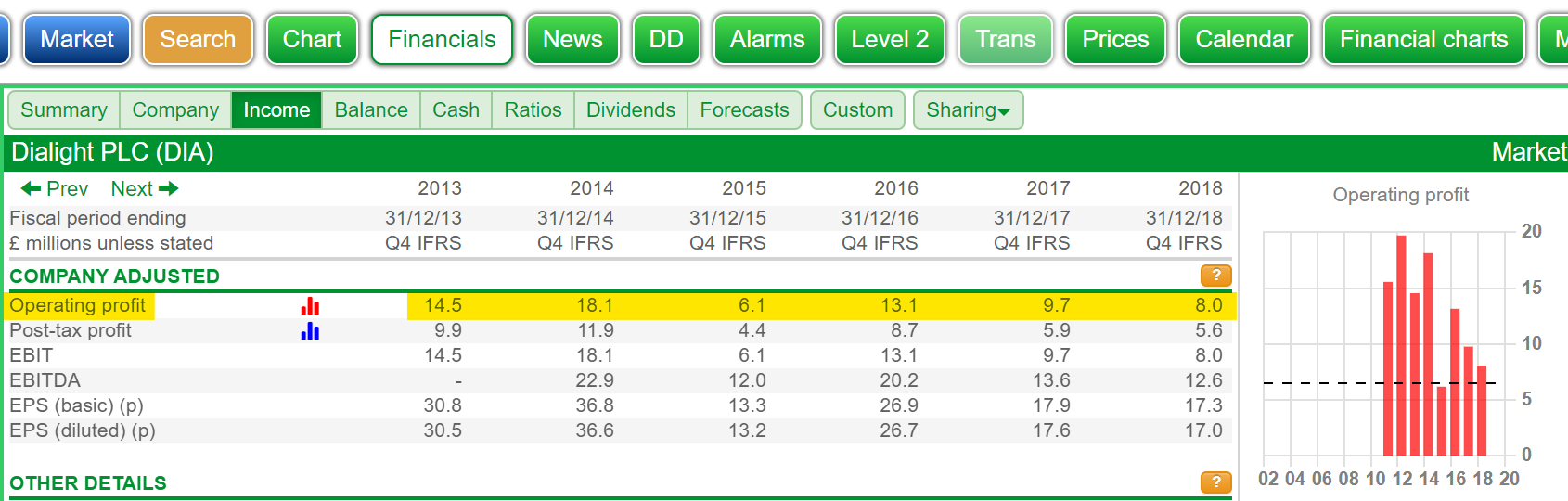

That year (2013), Dialight earned an adjusted operating profit of £14.5m, but the report speculated that operating profit might reach £69m four years later in 2017.

FW Thorpe’s stats weren’t bad in 2013, but it was worth about half as much and according to the PE ratio it was rated about half as highly. It was less profitable in terms of return on capital, and its growth was far more modest:

Though both companies make lighting fixtures, they are very different businesses. Dialight’s biggest geographical market is the USA, and FW Thorpe’s is the UK. While FW Thorpe makes lighting for factories, as well as lighting for offices, hospitals, schools, shops and so on, it is not a big competitor in Dialight’s hazardous heavy industrial niche.

What’s more FW Thorpe was an LED ingenue. In 2013, it had only been selling LED lighting systems for two or three years, and about 75% of sales were traditional lighting fixtures like fluorescent strip lights. It had learned how to design and manufacture LED lighting from scratch and analysts feared LED sales would cannibalize existing sales.

Saved by value discipline

I wish I could say my deep industry understanding enabled me to predict FW Thorpe would be a winner and Dialight would be a loser as customers rushed to embrace low maintenance and energy saving LEDs, but I knew even less about lighting then than I do now.

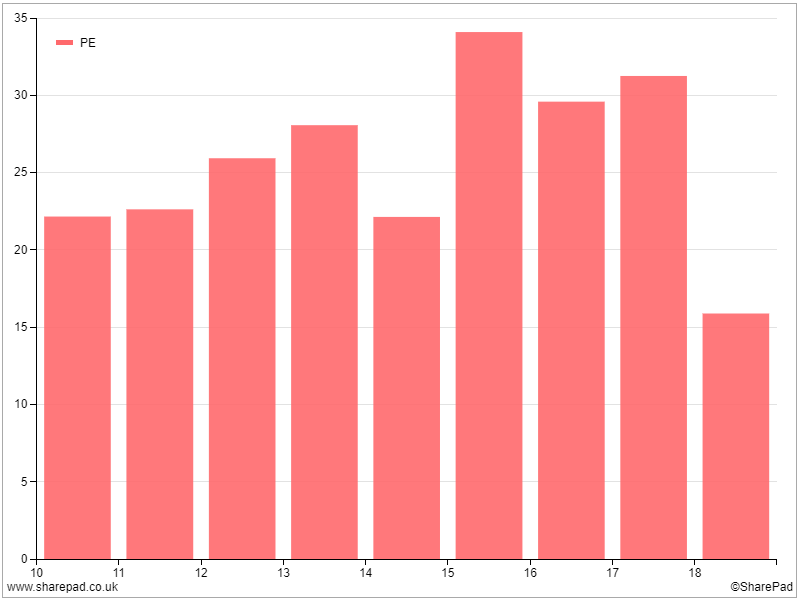

Two things stopped me investing in Dialight: a feeling that I did not understand the risks, and fear of the company’s growth company rating. As you can see, Dialight traded on a PE ratio of over twenty for most of the decade, and over 25 in 2012 and 2013:

Turning the clock forward, here are the latest stats for the two companies. At FW Thorpe profitability has held up as it has converted its product range to LED and it has grown strongly as customers have switched to more efficient and functional lighting systems (it’s been rewarded by investors with a much higher PE rating too):

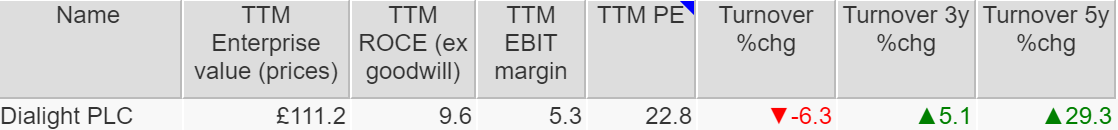

It is also by far the more highly valued company now. Dialight, as you would expect from the decline in the share price, has shrunk in terms of its market (enterprise) value. Investors have lost confidence because its performance is so poor:

Single figure returns on capital and profit margins are not hallmarks of a high quality company and far from earning an adjusted operating profit of £69m in 2017, Dialight’s operating profit peaked at £18.1m in 2014. In 2018, the last reported year it was just £8.0m:

According to SharePad, Dialight will announce its results for the year to December 2019 next month in March, and its performance will have deteriorated still. In a trading update last November, the company said it expected to earn adjusted EBIT (akin to operating profit) of between £5m and £8m, compared to £8m in 2018. If we include exceptional costs of at least £8.7m it will report a statutory loss.

Picking over the bones…

You may at this point be wondering what went wrong, considering it seemed Dialight was set up for success.

A crash in the oil price in 2015 revealed Dialight’s heavy industrial niche was not as attractive as people thought. Dialight’s lighting systems are used on oil rigs, in refineries, and in the factories of companies that supply oil companies with plant, and since they were all making less money they cut back on investment, including lighting.

The slump in demand exposed another deficiency, this time within Dialight. Despite the fact it was making a high value specialised product, it was making proportionally less profit on each sale (it had lower profit margins) than FW Thorpe. This still generated high returns on capital in the boom years when Dialight was selling in higher volumes, but as volumes fell, so did profitability. Dialight’s new chief executive said the company had let costs spiral out of control as it strained to meet demand because it had made too many product variants often designed for individual customers, and it was poor at forecasting and purchasing. His solution was to focus on what Dialight did best, designing and selling lighting, and outsource what it was doing badly, manufacturing.

It also planned to emerge from its newly uncomfortable niche, targeting less heavy industries as well as schools and prisons, not only in North America, but also in Europe.

The first part of the strategy, outsourcing, was a disaster, though, and has been reversed by an even newer chief executive, the current one, who joined in early 2018 and has in-sourced assembly again. The exceptional costs the company will report in March stem from this switcheroo, but the impact of Dialight’s manufacturing ineptitude goes much further than money wasted on air-freighting products to customers in a rush, and running outsourced and insourced operations simultaneously. Dialight has delayed orders, taken longer to get new products to market, alienated customers and staff, and lost ground to rivals. Although Dialight still claims a 27% share of the £500m heavy industrial market, that is less than it used to be.

The second part of the strategy, diversification, has yet to happen because the company has been so preoccupied with the first. Meanwhile the lighting companies in those markets have developed fully-fledged LED ranges of their own.

Taking back control

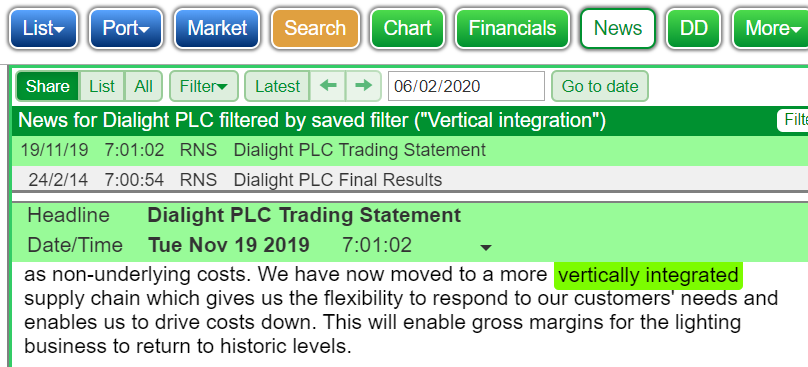

Now you’re probably wondering why I have bothered to get reacquainted with Dialight since it still looks like a horror show. The answer is management has uttered the magic words, vertical integration:

Other companies, like model train company Hornby and smoke alarm supplier FireAngel, have also made a hash of outsourcing. I take the view that if a company can manufacture its own products and still make good returns on capital it has the best of both worlds: control and profit.

That’s not to say I’m a convert to Dialight. We do not yet know if it has learnt to manufacture efficiently and it must also find customers in new industries, customers who are already ably served by the likes of FW Thorpe and other, bigger competitors on the global stage. If it doesn’t then the high costs of running its own factories are likely to come back to haunt it every time heavy industry experiences a setback.

Let’s just say I’m watching Dialight again, now it’s taking back control.

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.