This article has not turned out as I had expected.

I searched on SharePad for magnificent dividend histories, and thought I would be evaluating a business with glorious financials and tip-top management.

I have instead ended up with accounting alarm bells and a dissident shareholder trying to oust the boardroom.

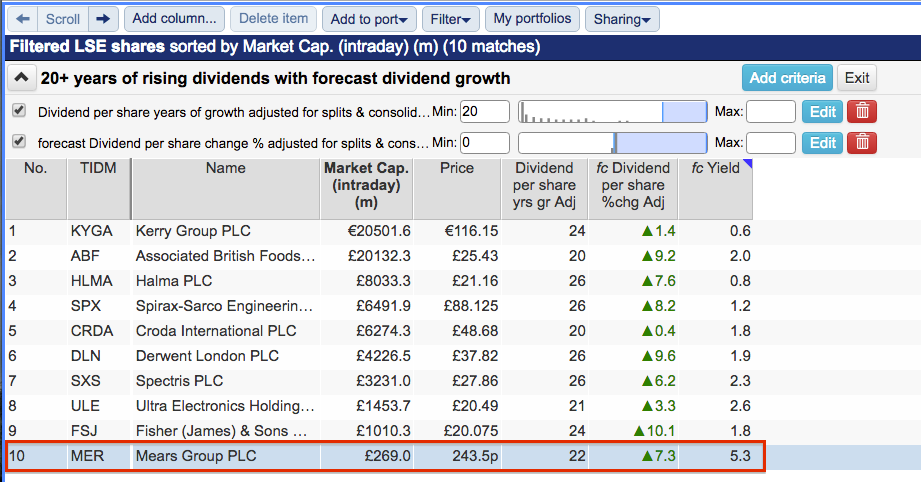

The screen I applied in SharePad was very straightforward. I looked simply for companies that offered:

* A 20-year (or more) record of dividend increases, and;

* Forecast dividend growth for the current year.

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 18/12/19: Mears” filter within SharePad’s brilliant Filter Library. My instructions show you how.)

SharePad returned only 10 shares, including a number of popular ‘quality’ names such as Halma, Spirax-Sarco and Croda.

I selected Mears, a £269 million provider of housing-maintenance and social-care services, due to its forecast 5.3% yield.

I was intrigued why the 5.3% potential income was much greater than the yields on offer from the other nine shares.

Having now evaluated Mears using SharePad, I have discovered why.

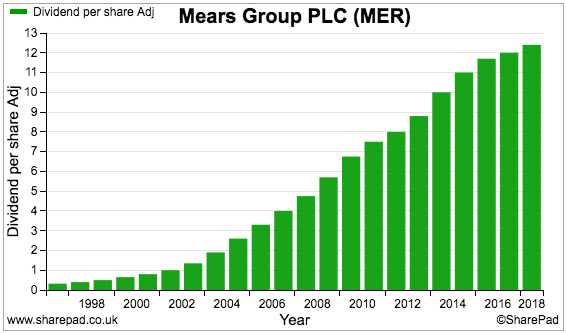

The chart below displays Mears’ wonderful dividend history:

Let’s take a closer look at the company.

The business of Mears

Mears was established during 1988 as a small maintenance contractor operating from a portacabin in Gloucestershire.

Three decades later, the business is now a prominent provider of property repairs and maintenance services for local authorities and housing associations. Mears currently looks after more than one million homes and undertakes approximately 6,000 repairs every day.

The group also provides domiciliary care services on behalf of local councils and NHS Trusts. More than 15,000 elderly or vulnerable residents receive assistance in their own homes through Mears.

The group’s line of work appears reassuringly predictable and not obviously sensitive to economic conditions. Furthermore, the provision of such repair and care services are underpinned by multi-year contracts.

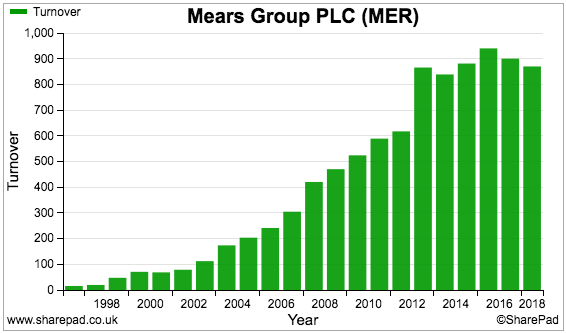

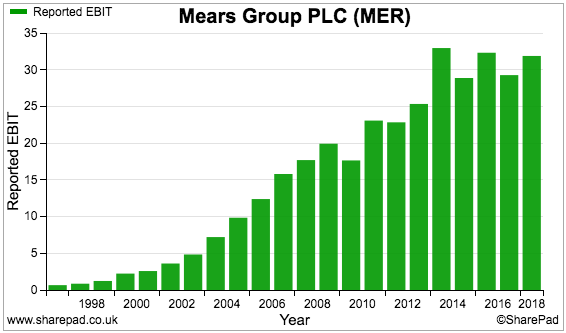

The illustrious dividend certainly supports the notion of a reliable operator, and the group’s revenue and profit histories showcase significant growth as well:

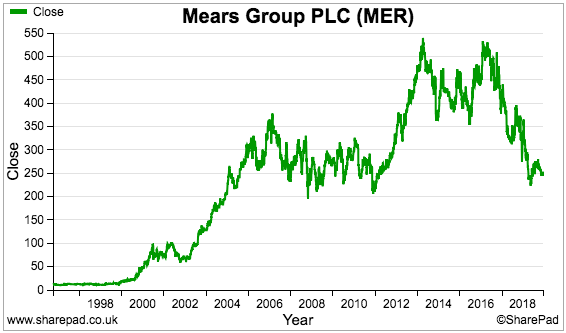

Mears joined the stock market during 1996 and the shares stagnated at around 12 pence for three years — but then proceeded to soar more than 40-fold:

However, the shares have lost approximately 50% of their value during the last few years. The market has gradually realised Mears may not be so reliable after all.

Mears’ SharePad Summary

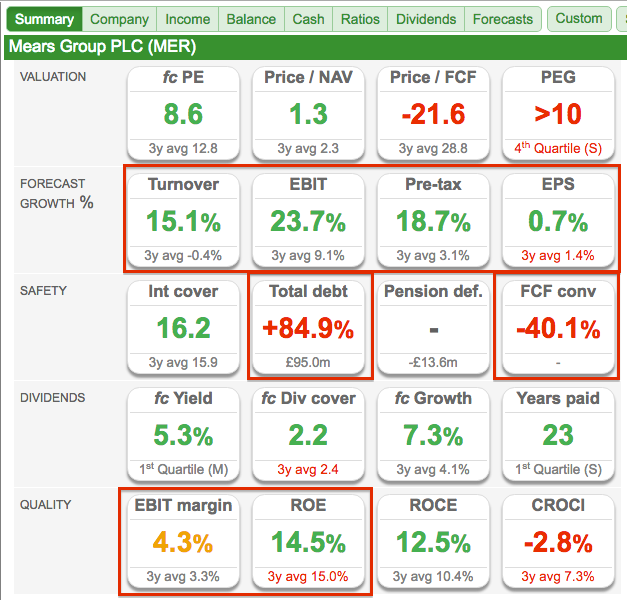

The SharePad Summary for Mears is shown below:

The important points are:

- The forecasts for the current year are positive (second row);

- Total debt has increased significantly while earnings have alarmingly converted into negative free cash flow (third row);

- The low margin and the average ROE (fifth row).

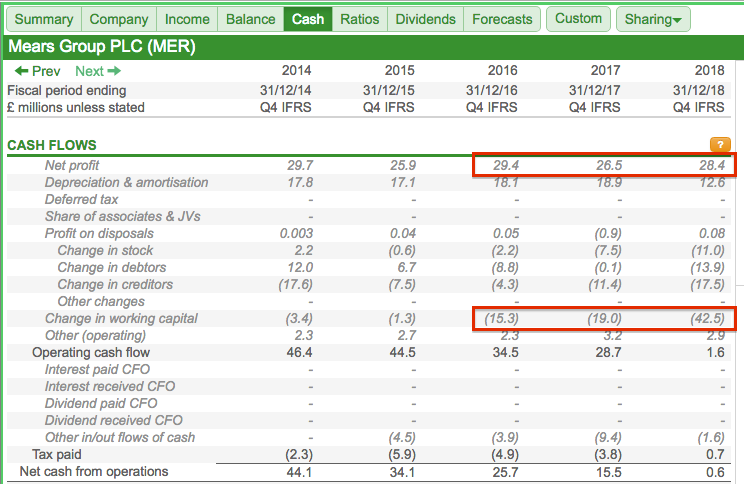

We must begin with the lack of cash conversion.

Cash conversion

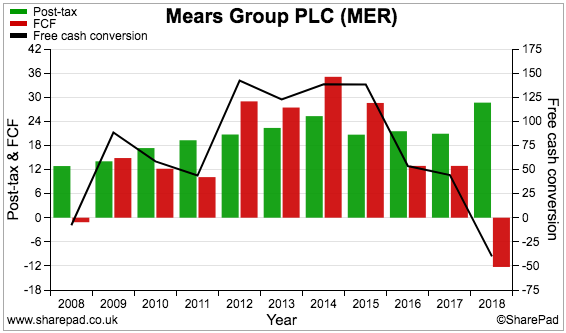

Mears’ cash-conversion percentage (black line, right axis) has deteriorated badly during the last three years:

Indeed, the negative free cash flow reported for 2018 has obvious implications for sustaining that majestic dividend.

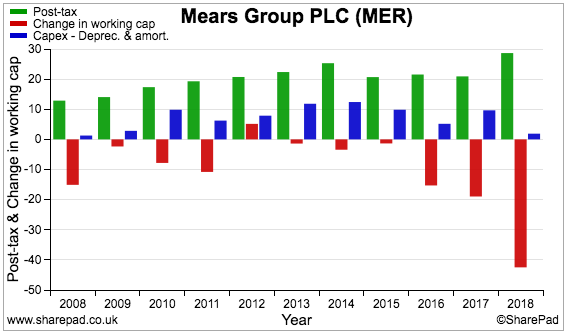

This next chart compares Mears’ earnings (green bars) to working-capital cash movements (red bars) and capital expenditure over and above the depreciation and amortisation expensed against earnings (blue bars):

The obvious reason for the increasingly awful cash conversion is working-capital movements.

SharePad’s numbers show that during the last three years, cash of £77 million has been needed for additional working-capital purposes:

That £77 million working-capital investment is enormous — and very unnerving — given total earnings (net profit) were £84 million during the same time.

Perhaps the cash-flow economics of the contracts Mears now undertakes are not as favourable as they once were.

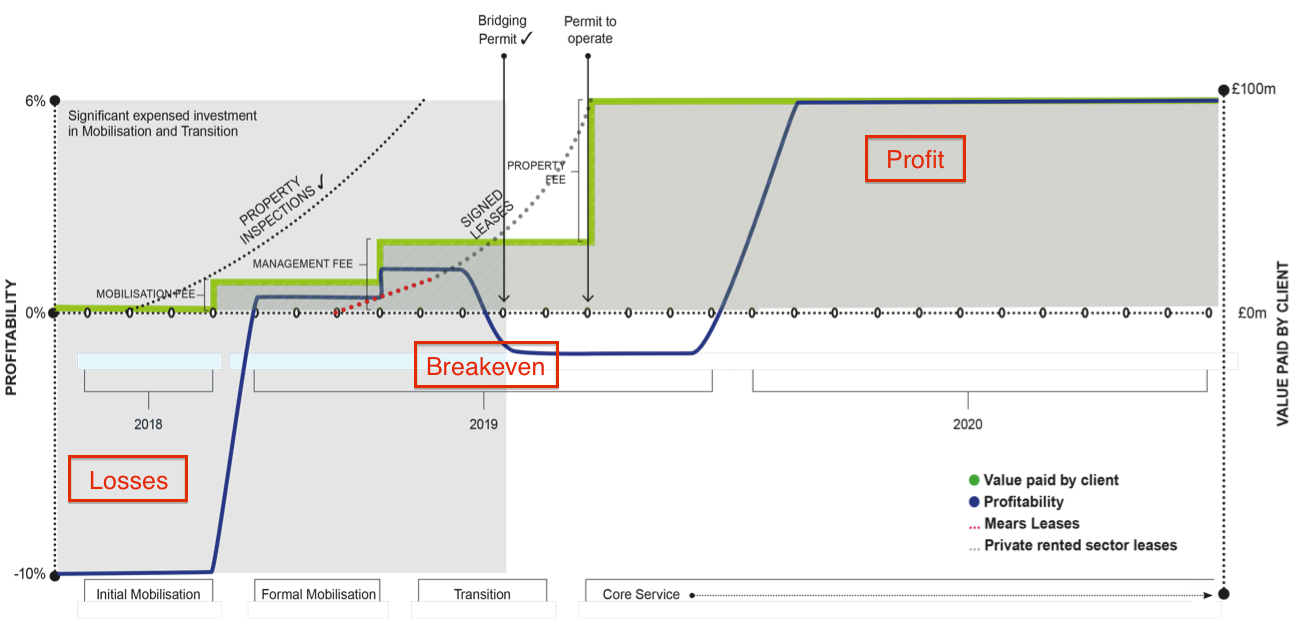

The following slide taken from a Mears presentation shows an example contract only recouping its initial losses (dark blue line) after 18 months:

A mix of upfront costs and customers paying in stages is never going to produce smooth cash flow — especially if many large contracts are involved.

Anyway, diverting approximately 90% of reported earnings into extra working capital does prompt two immediate questions:

1) Can reported earnings be relied upon when so little free cash is generated? (I am doubtful), and;

2) Where has the cash come from to sustain that impressive dividend? (SharePad tells us below).

Debt and acquisitions

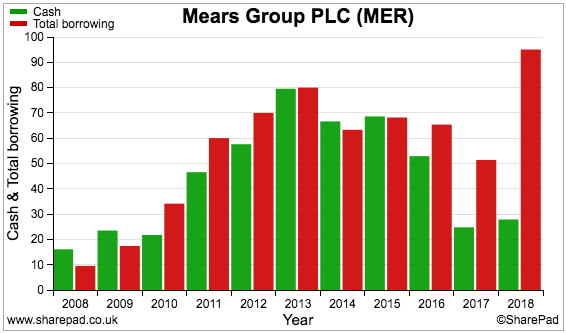

Mears has funded recent dividends by using its existing cash resources and by taking on more debt.

The chart below compares Mears’ cash position (green bars) to borrowings (red bars):

You can see cash and debt were equal at almost £70 million for 2015. However, by 2018 cash had dropped to less than £30 million while debt had soared to £95 million.

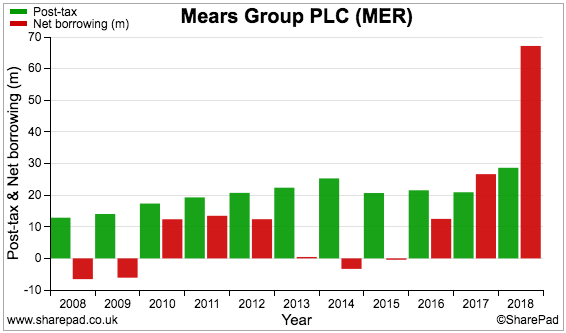

In effect, net debt has increased by approximately £65 million (to £67 million) during the last three years.

What’s more, net debt (red bars) is now more than double reported earnings (green bars) — and unusually high by the company’s past standards:

As well as dividends, the extra debt has been used to fund acquisitions.

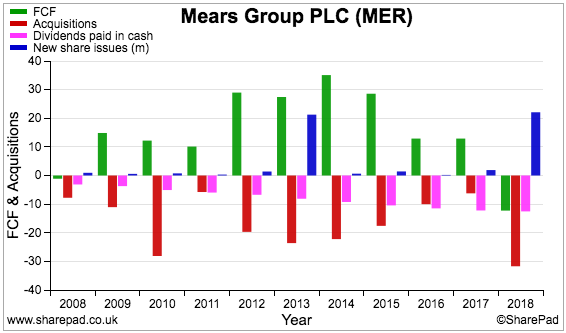

This next chart is unsettling. It compares free cash flow (green bars) to acquisitions (red bars), dividends (pink bars) and money raised from share issues (blue bars):

Mears is clearly very acquisitive — in fact, every year since 2001 has witnessed cash spent on other businesses (total amount: £223 million).

(As I mentioned during my recent SharePad webinar, acquisitions do create extra risk for investors. In particular, the purchases could i) signal the existing business is struggling to grow, and/or ii) lead to integration problems that distract management. The very best businesses tend to grow ‘organically’ (i.e. without acquisition)).

During 2018, Mears issued new shares worth £22 million to help fund an acquisition. A similar amount was raised during 2013, while a further £25 million was raised during 2007.

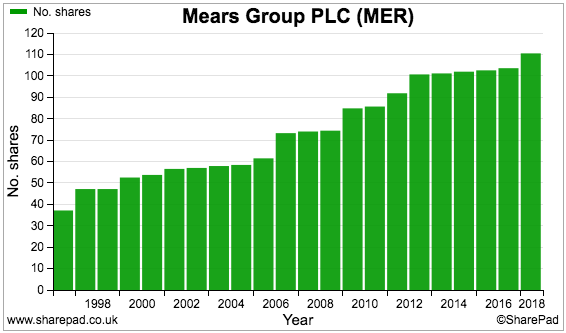

The share-count history is always worth checking when companies raise new money through shares. Mears’ share count has increased considerably over time:

Margin and ROE

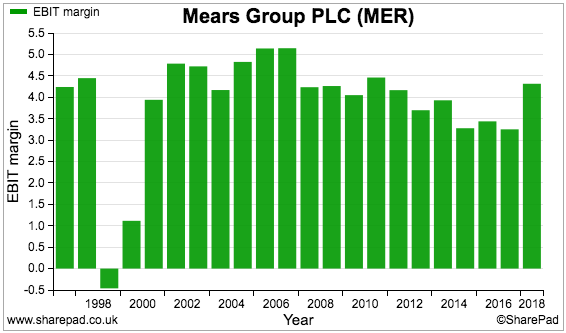

Mears’ operating margin has rarely topped 5%, which suggests the group has to price its contracts very competitively:

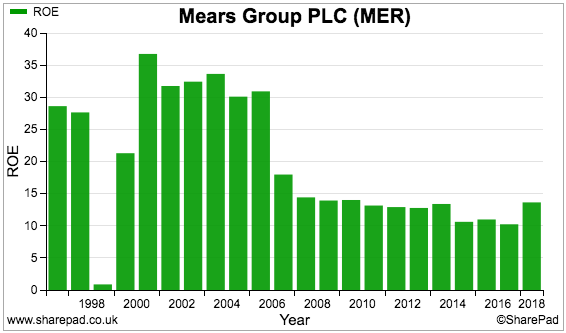

ROE has meanwhile not exceeded 15% since 2006:

The ratios are not exactly inspiring, and the margin and ROE declines since 2007 coincide with the diversification into care services.

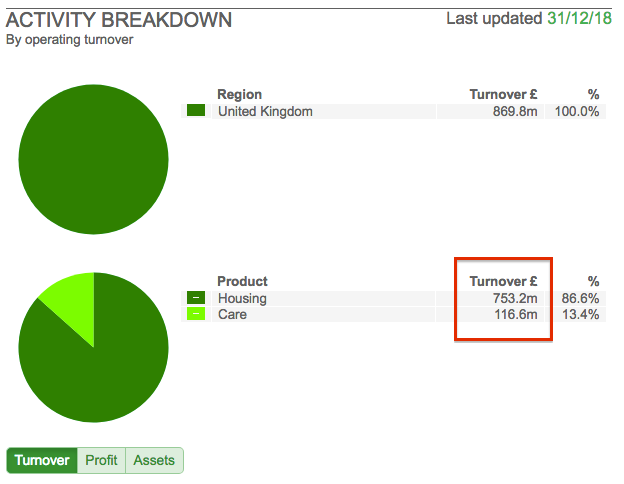

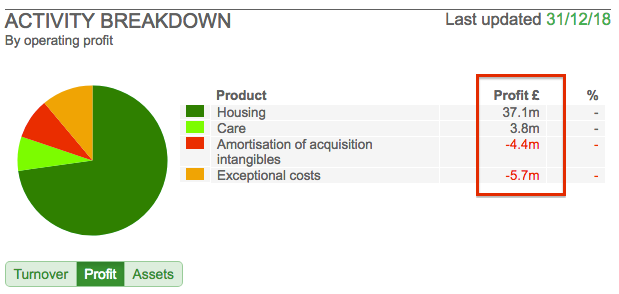

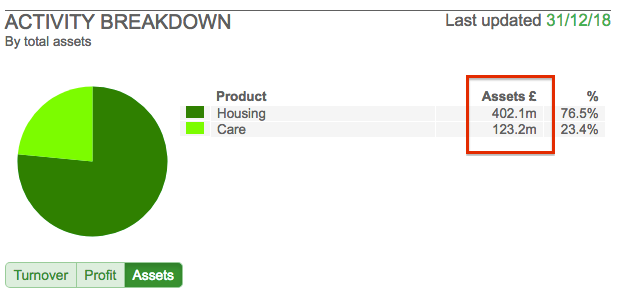

SharePad’s ‘Activity Breakdown’ statistics reveal revenue, profit and asset information for the property-maintenance and care-service divisions:

Care-service margins are 3% versus 5% for property maintenance, while care-service return on assets are 3% versus 9% for property maintenance.

The improvement to both the group’s margin and ROE during 2018 follows the exit of certain marginal care-service contracts.

IFRS 15 and revenue recognition

Oh dear — I must now turn to IFRS 15 and the annual report.

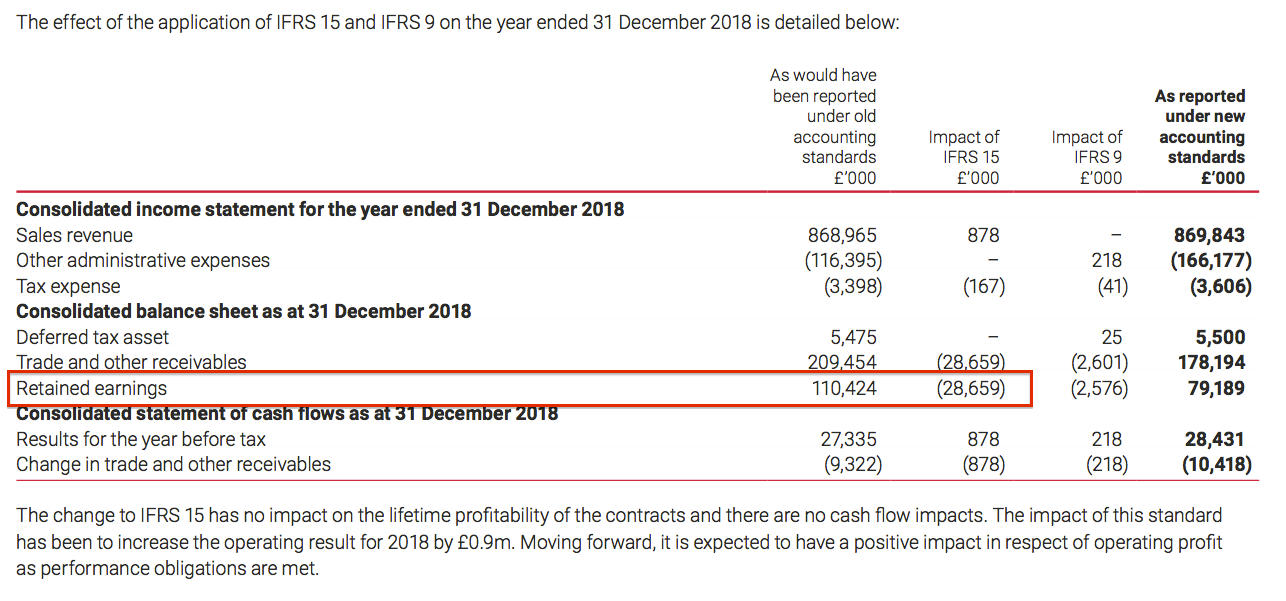

I touched on IFRS 15 within my Dotdigital article, and this new accounting standard has significant implications for Mears.

To recap, IFRS 15 was introduced last year and applies a more conservative approach to revenue and profit recognition — although the actual effect is often hidden away in the accounting notes.

Mears provides an instructive example of the impact of IFRS 15 — after all, the company’s multi-year contracts generate just the type of income IFRS 15 aims to clarify.

The relevant accounting note is shown below:

Retained earnings — representing the group’s accumulated past profits less dividends — declined by £29 million due to IFRS 15.

This reduction implies aggregate past earnings were ‘overstated’ by £29 million — equivalent to a significant 25% of retained earnings before IFRS 15.

To be fair to Mears, the company is correct when it states “the change to IFRS 15 has no impact on the lifetime profitability of the contracts and there are no cash flow impacts.”

In addition, Mears is also correct when claiming IFRS 15 is “expected to have a positive impact in respect of operating profit as performance obligations are met”.

Mind you, the “positive impact” is simply those ‘lost’ earnings of £29 million now being recognised under IFRS 15 in future years.

Mears seems happy enough to report those earnings of £29 million for a second time…

… although investors who based their valuation sums on the £29 million the first time around (pre-IFRS 15) may not be so enamoured!

I must add that the annual report reveals some other concerning statistics.

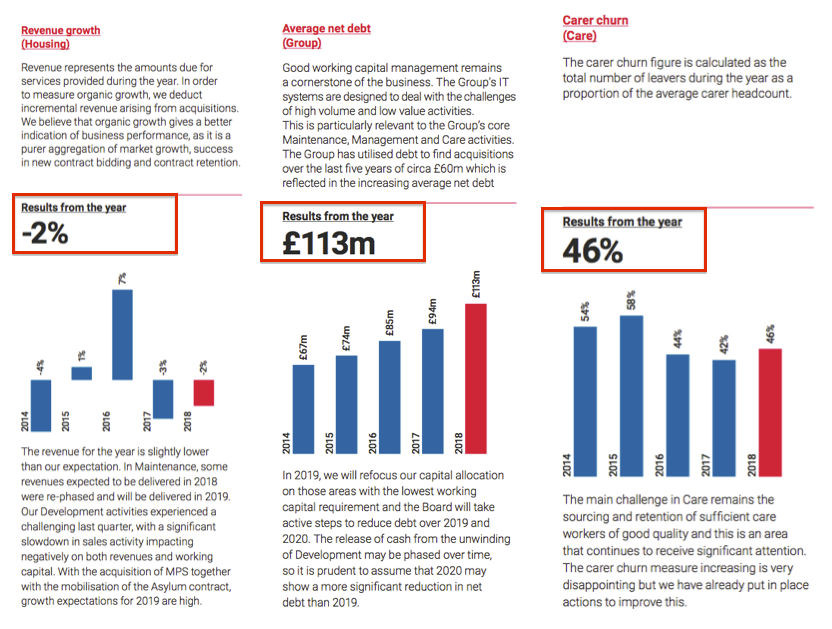

In particular:

* Underlying revenue from the main housing division has effectively stagnated during the last five years;

* Average net debt of £113 million for 2018 is materially higher than the £67 million year-end net-debt position — which hints at balance-sheet ‘window dressing’, and;

* An astonishing 46% of care-service employees leave every year.

Latest results and dissatisfied shareholders

Interim figures published during August were mixed, with turnover up 10% to £481 million and underlying pre-tax profit down 10% to £17 million.

The first-half dividend was lifted 3%, which reflected “the Board’s confidence in the future whilst being mindful of the importance of maintaining a prudent capital structure.”

The directors also said they were “committed to delivering a controlled unwinding of working capital… and the expectation for the full-year is to see a reduction in working capital utilisation, with a more significant reduction in 2020.”

The “unwinding” resulted in a £2 million return of working-capital cash — which I suppose is a start against the £77 million previously invested in working capital during 2016, 2017 and 2018.

The following results commentary was startling:

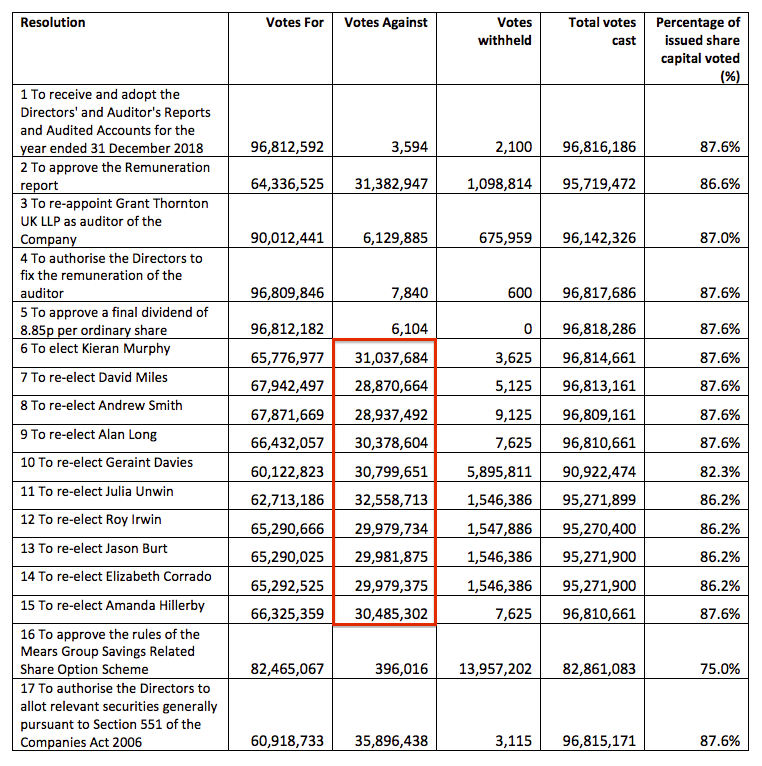

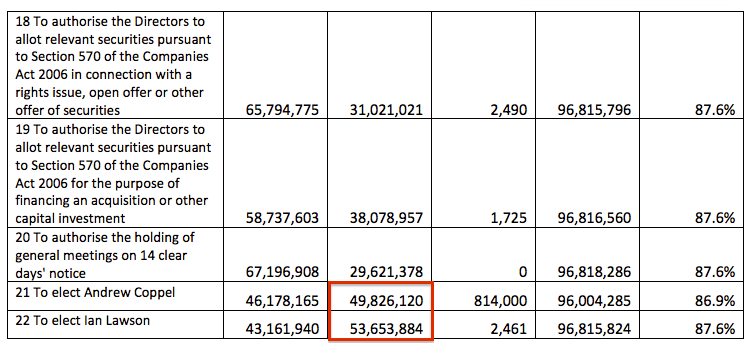

“The Board noted that Resolution 2 (concerning the approval of the remuneration report); Resolutions 6 to 15 (concerning the election or re-election of each of the Directors); Resolution 17 (concerning the general authority to allot relevant securities); Resolution 18 to 19 (concerning the authority to issue ordinary shares without a pre-emptive offer), Resolution 20 (concerning the holding of General Meetings on 14 days’ clear notice); and Resolutions 21 and 22 (which were requisitioned by PrimeStone Capital Irish Holdco DAC concerning the appointment of two additional Non-Executive Directors), received 20% or more votes against the Board’s recommendation.”

I cannot recall another company where so many AGM resolutions attracted so much dissident voting.

The resolutions to re-appoint every director received protest votes of at least 30%:

(I note the auditors — Grant Thornton of Patisserie Valerie notoriety — got off lightly with just a 6% protest vote.)

The results statement blithely noted: “The Board recognises that a number of shareholders are dissatisfied with the performance of the Company and its share price.”

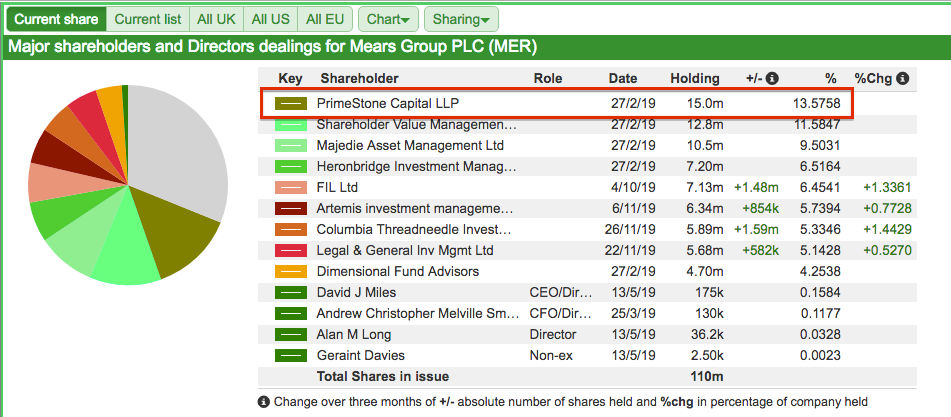

The “dissatisfied” shareholders are led by PrimeStone Capital, which owns nearly 14% of the shares and has commendably made its views public:

Primestone is (understandably) not happy with Mears’ financials, and claims the board:

* “Has failed to evaluate the situation and take the necessary corrective actions”, and;

* “Lacks critical financial and commercial competencies needed to restore Mears’ performance”.

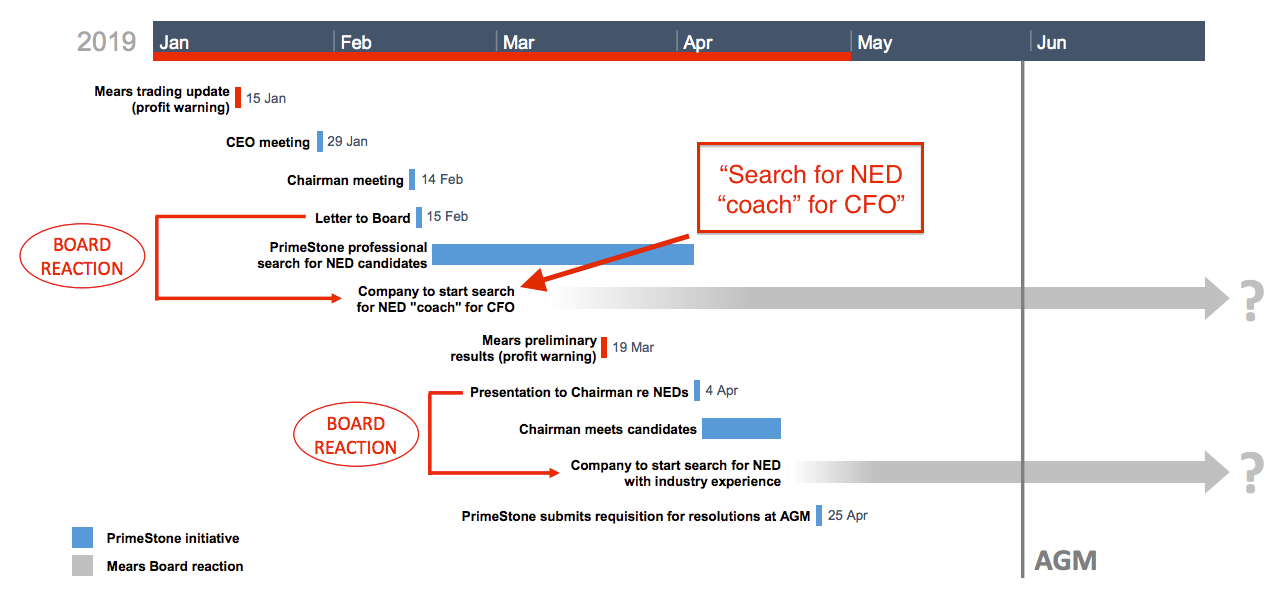

I am not sure what to make of this slide from Primestone, which suggests Mears has admitted the finance director needs a non-executive “coach”:

Perhaps Mears really needs a new finance director instead.

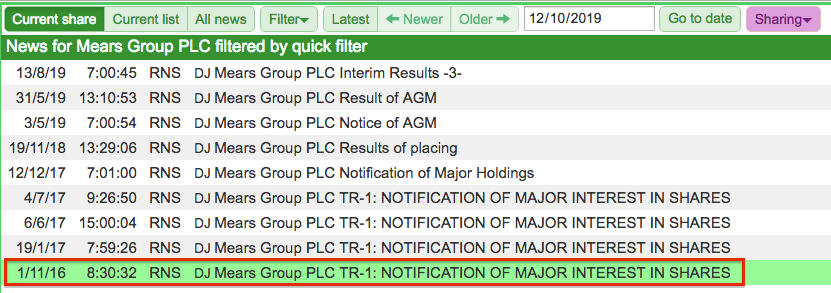

Primestone proposed two non-execs at the AGM, both of whom failed to garner enough support:

I should add Primestone first disclosed an interest in Mears when the shares were around 450p during late 2016:

Primestone’s subsequent activism therefore seems unlikely to have been planned at the time of purchase.

Forecasts and summary

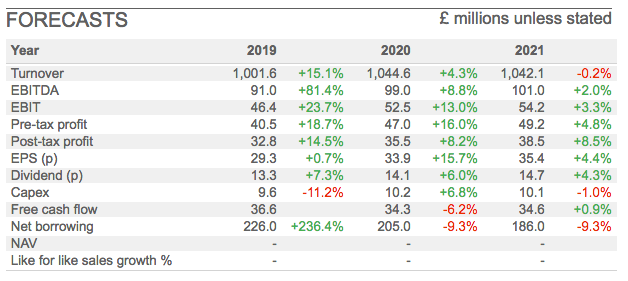

City forecasts for Mears are not straightforward. Projections for revenue and profit growth for 2019 vary between 1% and 81%:

New contracts, recent acquisitions, IFRS 15, the increased share-count and exceptional items all account for the spread of estimates.

The net borrowing forecast appears very disturbing — up 236% to £226 million.

That projection just adds to the alarm bells already sounded by SharePad, the annual report and Primestone.

Earnings not converting into cash, sizeable acquisitions, significant debt increases, IFRS 15 suggesting past earnings were overstated, a hint of balance-sheet ‘window dressing’, a lack of underlying growth within the main division, a coach for the finance director…

…and all that is before considering how the wider outsourcing sector has become an investment disaster zone after mishaps at Capita, Carillion, Interserve, Kier and Serco. I just wonder whether the general economics of public-service contracts continue to add up.

Throw in some adverse scuttlebutt, too, and I start to ask myself how Mears’ illustrious dividend run has actually kept going for so long.

Until next time, I wish you happy and profitable investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Disclosure: Maynard does not own shares in Mears.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.