The key thing to stress at the beginning and, as many of you will already be well aware, there are many ways to become a good investor. There are many different techniques, many different styles and strategies from fundamental analysis, technical analysis to even astrology and Biorhythms.

It sounds like a cliché but the best way to become a good investor is to find what works for you and helps you achieve your investment goals. By all means read all the books (I own a huge number of investment books many of which I disagree with) and articles like this one but ultimately you should cherry pick the ideas that you can understand and that you believe in.

I regard myself as a conservative investor. I’m not expecting to make big percentage returns every, or even most, years. I’m content with a modest annualised return – I target a total return of inflation plus 5%.

Let’s start this piece with seven ways of thinking / tools that work for me:

1. What are you trying to achieve?

First question is you will be asked by an investment advisor is: Do you want to grow your investment pot or have extra income? There is no necessity to choose dividend income or capital growth – capital growth can be converted into income and dividends can be re-invested.

There can be tax differences (which will depend on your individual circumstance) but they are usually small compared to importance of choosing a good investment.

Always be aware of the cost of your decisions: reinvesting a small amount of dividend could incur a disproportionate cost.

2. Don’t underestimate what you know

Where I personally have been very successful is to make major plays (compared to my liquid wealth) in areas where I really understand what is going on and have my own insight into the potential. Not everyone will have exposure to these opportunities but if you do come across such a situation and you are convinced that the downside is much smaller than the upside I encourage you to ‘go for it’.

3. Be your own devil’s advocate

The test I apply when I decide to buy a share is to think through persuading a significant other, life partner, parent or mentor, that this investment is a solid investment. Use specific financial arguments rather than generalised persuasion. Imagine what objections they would come up with – what if the CEO goes under a bus, what if they can’t roll over that loan, what if interest rates double etc. Write it down. I use my father who was army before becoming a stockbroker – I can tell you that my internalised father is a tough guy to persuade.

4. Trust no one… without properly and comprehensively thinking it through for yourself

I’d never buy a share that someone was ‘selling’ me. Stockbrokers are salesmen not your best friend or even your friend.

I have a healthy distrust of experts too. Some of you will remember Bob Beckman – he had a regular slot on LBC in the 80s talking down the economy and the market. I own his book “Downwave – everything all the experts would tell you if only they dared”. Published in 1983 it got everything wrong – but he was clearly smart, he was an engaging speaker, he was wealthy. What I would suggest you learn from this is to listen to experts and pundits with respect but never follow their ideas without really thinking them through for yourself. Give ideas a good kicking before you accept them. There will be some areas of uncertainty but if you look carefully at those areas and are not relying on advice from someone who benefits from your investment then you just have to make a judgement call.

If anyone says: “you’re a sophisticated man of the world” or “you’re a sophisticated investor so you know that …” be very suspicious. I delight in not understanding the ‘obvious’ truth they are trying to sell you and getting them to explain it to me properly, slowly, step by step, which they always fail to do. That is the smart thing to do: challenge what you don’t fully understand.

5. Patience is a virtue

Good companies that deliver improving results will eventually be rewarded with a higher share price. To almost quote Warren Buffet (and others): In the short term the market is a beauty competition, in the long term it is a weighing machine.

I’ve recently moved my office from one floor to another last week and I came across an investment book published in 1945. They talk about 25 year moving averages without irony. That’s what I call a long term market view!

6. Diversification – everyone says it, because it’s true

How you allocate your investment is probably more important than the granular detail. So, owning a house, any house, is more important than which house. The decision to own equities is generally more important than which equities as long as you have a diversified portfolio.

Diversification is a really good idea. With a small sum you might select 3 shares in 3 unrelated sectors. With a larger sum to invest I would look at 10 in 10 unrelated sectors as a good number. More than that wouldn’t add a lot to your diversification and may overstretch your research.

Conventional wisdom suggests that you should have an internationally diversified portfolio and when I started that’s exactly what I wanted to do. I quickly realised that it wasn’t quite that simple. In general it is still hard to own foreign shares, for example there may be complex tax rules to get your head around or money laundering issues. So, most people get international exposure through a fund. International funds typically attract a fee of about 1.5% + other non-transparent costs. I would posit that the main promoters of this conventional wisdom are investment professionals. I leave it up to you to draw your own conclusions.

Also, I realised that I spend most of my money in the UK, I understand UK companies better, so restricting myself to UK investments made a lot of sense. There are plenty of UK opportunities and adding extra cost and foreign exchange risk is often not, in my opinion, worth it.

7. Money management

I would suggest spreading your money equally between shares – unlike FTSE 100 which weights by capitalisation. Rebalance once in a while – but don’t overdo it.

Cost price averaging (buying shares regularly to take advantage of any dips in the market) is a really, really small idea. It does encourage more trades which benefits your broker – which is an interesting consequence of the idea.

I use stop loss alarms to trigger a review of whether I want to hold a share. If the justification you made before investing just isn’t credible any more: sell. As an investor you will take losses. It goes with the territory. Don’t take it personally – as the saying goes: Just do it.

https://www.sharescope.co.uk/sharepad_tutorial14.jsp

https://download.sharescope.co.uk/doc/User_Guide/15_Alarms.pdf

So, there you go. They are the key considerations I use for my own portfolio but as I said at the beginning, they may work for you too or they may not but hopefully there is something in there that you can use… of course, there are many more ideas out there too if not.

How would I go about setting up a new portfolio?

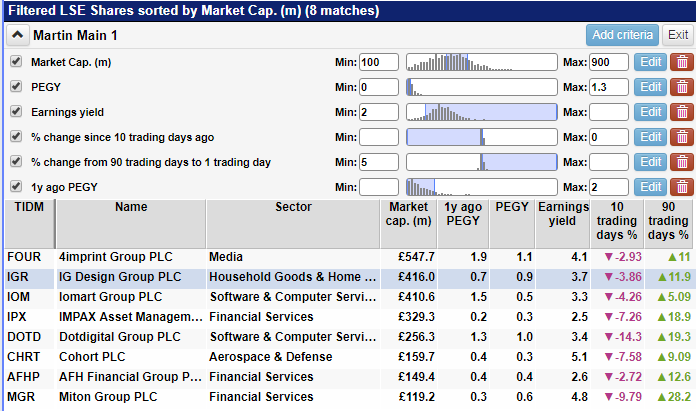

Below are the criteria I would use to filter stocks that I might be interested in exploring further:

-

- Cap £100m to £900m

- PEG / PEGY < 1.3

- Yield > 2% i.e. paying at least a small dividend

- If you are a shorter term investor you might include

- At least 5% growth in share price over last 90 trading days (positive momentum)

- Negative share price over last 10 trading days (buy on the dips)

- And optionally

- 1 year ago PEG / PEGY <2

These are relatively substantial growth companies. Here they are in my SharePad filter which was run on 25/11/18 but last time I checked they weren’t returning much at all given current market conditions:

(If you wish, you can find this filter in the library of filters within SharePad and run it yourself and play with the criteria. Simply go to: Filter -> Apply filter -> Library -> “Martin Stamp 10/01/19: How I build and manage my share portfolio”)

Now I would look at each share in detail.

What I’m always looking for are shares that are less loved but will be more loved in the future because they deliver on their promise.

Then I would be back to my points at the beginning of this article and ultimately back in front of my internalised father!

One last anecdotal thought for you on how I decide on if and when to sell – remembering of course that I regard myself as a conservative investor.

I bought Microsoft share after Windows 95 came out and doubled my money and I sold them. Over the next year the shares double again. But after another year they had retreated back to the level I had sold at. I would maintain that I correctly judged fair value for the shares and that I was right to sell when I did. I never want to buy or hold a share on a ‘greater fool’ theory: I think they’re overvalued but some fool will buy them at an even higher price. My experience and observation is that believing in “the greater fool” means that too often you end up being the greater fool.

Martin Stamp

ShareScope CEO & Founder

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.