In the chaotic business conditions we are experiencing, self-reliance has been a source of competitive advantage. Since we do not ever know what the future will hold, Richard goes in search of companies that have an element of vertical integration.

I hope it is not smugness, but I have felt a sense of satisfaction when companies I admire have posted resilient or strong results during challenging times.

The supply shortages businesses are experiencing as the economy adjusts to the pandemic and Brexit have resulted in extreme difficulties for companies unable to keep up with demand.

Reliable supply as a competitive advantage

Companies that have their own, or reliable sources of supply are at an advantage.

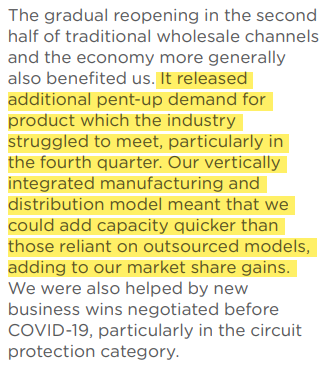

Luceco, a manufacturer and distributor of electrical products and lighting, commented in its annual report that:

Source: Luceco annual report

Companies like Solid State, a supplier of electronic components and manufacturer of rugged electronic equipment, James Latham, an importer and distributor of timber, FW Thorpe, a manufacturer of lighting, and James Halstead, a manufacturer of vinyl flooring, have all published results recently.

Were you to read the numbers alone you might not realise they had experienced any difficulty at all, although the narrative accounts tell of the challenges they faced.

An element of vertical integration has served these companies well. They are not just manufacturers or importers. They maintain high levels of stock, to give them a buffer to fall back on when the worst happens so they do not disappoint customers.

They also own or have close relationships with their suppliers, and they collaborate closely with customers, which means suppliers and customers stick with them even if lead times are growing and orders must be delayed.

When complicated supply chains are breaking down, the companies that have internalised and simplified them prosper, at least relative to companies that depend more heavily on others.

But the benefits of vertical integration go beyond our current circumstances. Vertical integration can define a company and its place in the market. It can also be a burden.

The light and dark sides of vertical integration

A vertically integrated business performs many of the activities required to bring a product to market.

One example is Hotel Chocolat. You probably know from its shops but an increasing proportion of sales are online, or by subscription.

Through its shops and subscriptions Hotel Chocolat knows its customers well, but it also invents new chocolate products and manufactures them.

Ninety-five percent of the chocolate it sells is made by its factory in Huntingdon, which recently doubled in size and will double in size again by 2023.

It farms cacao on an estate in St Lucia in the Caribbean.

Hotel Chocolat does not do everything. You can buy its chocolate in John Lewis, most of the cacao comes from small farmers in Ghana, and online fulfillment is outsourced to THG (The Hut Group), but the company has first-hand knowledge of pretty much every aspect of the business.

This gives it control over the product, which is important because it is more expensive than supermarket and corner shop chocolate. To justify the price tag, it must be better.

Even if Hotel Chocolat does not own all of its cacao supply, by operating farms it is armed with the expertise required to help suppliers reach the ethical and efficiency standards it aspires to.

Games Workshop is one of the most vertically integrated businesses I know.

As it turned a cottage industry, modelling and wargaming, into a mass hobby, Warhammer, Games Workshop behaved like the industrial giants of the early twentieth century, car manufacturers that owned their own rubber plantations for example, and created the supply chain it needed for itself.

It owns the vast collections of stories and characters that fire up hobbyists’ imaginations, the means of producing the models it sells, the factories and machines, and the distribution warehouses.

It markets Warhammer through communities centered on its stores and an online community fed with cartoons, tv shows, and so on through its websites.

Any one of these capabilities would be formidable for a competitor to create. Together they probably make Games Workshop unassailable.

The dark side of vertical integration comes down to complexity and cost.

The reason businesses specialise, rather than try and do everything, is that in an ideal world companies are more efficient when they are focused on doing a few things well and can rely on each other to fill the gaps.

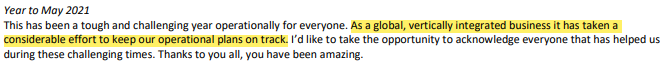

Trying to be good at lots of things is difficult. As Games Workshop’s annual report describes, adapting as the implications for workplaces shifted during the pandemic must have been especially difficult to cope with, when you operate such a wide variety of them:

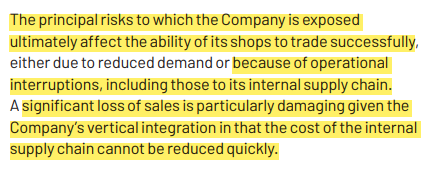

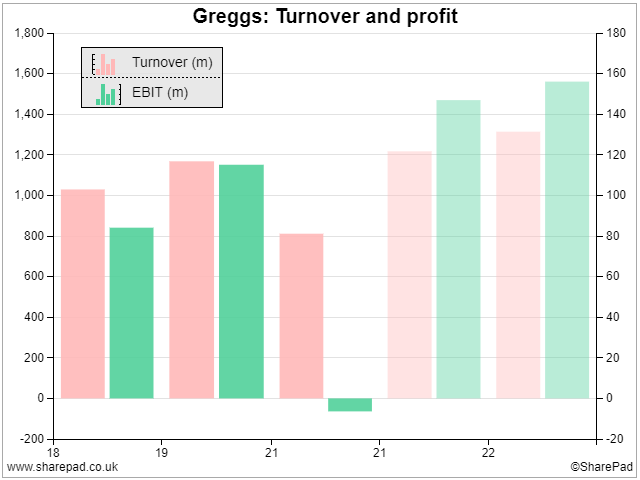

Greggs, which sells cheap pies and coffee on the go, explains the cost risk in its annual report.

Source: Greggs annual report

Usually a vertically integrated company will be committed to substantial fixed costs, bakeries, equipment, vehicles and so on that cannot be quickly or economically cut to defend profitability should there be a sharp decline in sales.

The result is a disproportionate fall in profit compared to sales when demand is weak. This effect is known as operational gearing.

Like Hotel Chocolat, Greggs had to close its shops during the pandemic and the impact on profitability shows how a fall in turnover can be magnified in an operationally geared business.

Greggs’ calculation is that over the long-term the benefits of vertical integration, secure and speedy supply, and the innovation of new products among them, outweigh the cost of vertical integration.

I believe the more unique the capabilities required to supply a product, the more the company providing it is likely to benefit from or even require vertical integration, and (provided people want the product) the more profitable the company is likely to be over the long-term.

The combination of high levels of profitability most of the time, prudent finances in case things get really tough, and a degree of vertical integration is something of a holy grail.

Finding vertically integrated companies

Normally I uncover vertically integrated businesses serendipitously, by downloading the latest annual reports of companies I might be interested in and reading about their business models, how they make money.

We can filter SharePad’s news feeds for company reports that use the terms “vertical integration” and “vertically integrated” in their stock market reports. I also have a collection of thousands of annual reports stored in a program called Evernote that allows me to search across the whole set for the same terms.

The drawback of these methods is that companies can be vertically integrated without flouting the jargon.

They are a start though, and searches and filters conducted for this article, as well as more serendipitous discoveries, have thrown up some surprising and some familiar names, which I have dumped in a SharePad portfolio for investigation.

The columns show debt to capital, as a proxy for financial prudence, and return on capital employed as a proxy for profitability.

The impact of the pandemic on certain industries may mean these statistics do not necessarily reflect normal levels of profit and debt, so they need to be interpreted carefully.

Twenty vertically integrated businesses

|

Name |

Turnover (£m) |

TTM ROCE (%) |

TTM Debt to capital (%) |

Notes on vertical integration |

|

AB Dynamics |

156.5 |

2.6 |

0.9 |

Designs, manufactures and sells vehicle testing equipment direct to vehicle manufacturers |

|

Burberry |

7697.2 |

14.2 |

44.6 |

Designs, manufactures and retails luxury clothing and accessories |

|

Castings |

403.6 |

2.7 |

Casts, machines and assembles components for commercial vehicle manufacturers | |

|

Churchill China |

161.3 |

4.8 |

20.1 |

Manufacturer of tableware for hospitality industry, owns its clay supplier |

|

Cranswick |

5002.7 |

14.6 |

16 |

Farms and processes pork and poultry products |

|

Dewhurst |

157.8 |

14.4 |

20.1 |

Manufactures, assembles, distributes and fits lift components |

|

DFS Furniture |

2693.2 |

15.6 |

62.9 |

Designs, manufactures (20%), retails and delivers furniture |

|

Games Workshop |

879.5 |

72.6 |

20.1 |

Manufactures and retails fantasy models, publishes stories, games, and content |

|

Goodwin |

402.8 |

11.4 |

21.9 |

Collection of vertically integrated engineering businesses |

|

Greggs |

3008.5 |

16.2 |

42.1 |

Bakes pies and pastries, and retails them through its own fast food outlets |

|

Hotel Chocolat |

433.3 |

10.3 |

35.1 |

Farms cacao, develops chocolate products, manufactures, retails |

|

Howden Joinery |

4642.4 |

27.6 |

Designs and manufactures cabinets, sells direct to small builders | |

|

Jet2 |

6944.5 |

-15.2 |

54.8 |

Leisure airline and package tour operator, sells direct |

|

Luceco |

512.2 |

43.3 |

21.3 |

Manufacture and distribution of electrical products and lighting |

|

Mondi |

18496.4 |

11.9 |

33.2 |

Manages forests, operates pulp and paper mills, manufactures packaging |

|

Next |

11968 |

25.7 |

70.5 |

Sources, distributes, retails fashions and homewares. Operates its own IT and fulfilment. |

|

Renishaw |

1695.7 |

11.6 |

12 |

Designs, manufactures, uses and sells machine tools |

|

Spirax- Sarco |

3589.1 |

17.8 |

34.7 |

Designs and manufacturers industrial equipment and sells it direct |

|

Whitbread |

4710 |

-11 |

53.7 |

Owns Premier Inn hotel properties, operations, brand, and inventory distribution |

|

XP Power |

628.3 |

20.2 |

15.9 |

Designs, manufactures, and sells power converters direct to equipment manufacturers |

Source: Exported to table from SharePad list view

Richard Beddard

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Hi Richard,

I think the benefits of vertical integration vary depending on the specifics of the company, but a recurring theme is that it can give the company:

(a) A close and direct relationship with the customer, which is an advantage over pure-play manufacturers who rely (to varying degrees) on distributors for feedback on what customers want.

This is partly why Domino’s (which I own) runs a small number of corporate stores alongside a thousand or so franchisee stores. Running stores gives the manufacturer (of pizza ingredients in Domino’s case) direct feedback on what customers like and don’t like, the issues they’re having and so on.

XP Power is also an excellent example of a company that uses its world-leading distribution network to feed information back into its design and manufacturing business.

(b) Control over the manufacturing process, which is something that pure-play distributors don’t have.

Pure-play distributors (as XP used to be) don’t control design or manufacturing so they’re reliant on third parties to produce products that customers want. This is okay, but it tends to lead to a focus on volume over added value, so pure-play distributors typically sell low margin relatively undifferentiated items.

Spirax Sarco or Senior or other engineering solutions providers leverage their ability to help customers design critical elements of power plants or manufacturing plants, and then they can go away and manufacture any bespoke components they require, knowing that they control the quality and supply of those components.

So I definitely agree with you that vertical integration can give a company material advantages over less vertically integrated competitors. But as you say, it does make running these businesses more difficult as they have to be competent across a wider range of activities, and that’s harder than being the master of one.