Richard takes a look at the segmental report of Cohort to gather insights into the company’s costs as it grows in complexity. The segmental report of another business shows how difficult it can be for companies to decide what they can and cannot tell us.

I am a fan of some versions of the buy and build business model

Generally, it works best when companies acquire businesses that are so similar they can be folded directly into the mothership, or they are so different they operate autonomously (reporting through head office’s finance function and drawing on its capital when both parties deem it necessary).

When acquirers mix it up, grant a bit of autonomy but also involve themselves in day-to-day operations, things can get a bit messy. “Messy” can be expensive.

Complexity risk in buy ‘n build

Bunzl (See A company that is already successful), a distributor of consumables like packaging and personal protective equipment, is a classic example of a business that assimilates similar but smaller rivals and becomes more efficient simply by being bigger (it can place larger orders with suppliers at lower prices, for example, and supply a wider range of goods to customers).

Cohort is a defence technology company that exists at the other end of the buy and build spectrum.

It acquires niche businesses that probably share some customers and may share some expertise with other companies in the group, but do something very different.

Its various companies include manufacturers, distributors, and consultancies. They supply sonar systems for submarines, counter-drone systems for airports, electronic warfare training and support, cybersecurity services, ear defenders for special forces, communication systems for naval vessels and traffic enforcement systems to local authorities.

One of Cohort’s strategies is to reduce its dependence on the UK Ministry Of Defence, by acquiring businesses that either export or are domiciled abroad (it owns German and Portuguese subsidiaries).

Managing an increasingly sprawling set of niche businesses centrally would not be efficient, so Cohort chooses to give its subsidiaries a high degree of autonomy.

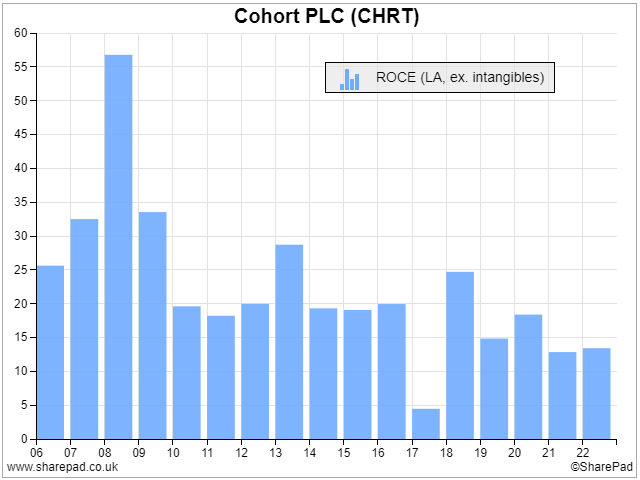

However, something is reducing Cohort’s profitability:

There are probably many factors behind the decline. Cohort has sought to diversify partly because its biggest customer, the UK MOD, has been in a funding straitjacket for many years (though that is changing).

It acquired its most profitable business, MASS, in 2006, when it was one of only two subsidiaries. MASS is highly profitable and almost inevitably the acquisition of good but not-so-great businesses has diluted its contribution.

In the last couple of years, two of Cohort’s more recent acquisitions have experienced difficulties at least partly of their own making. Cohort has changed the management of these subsidiaries and how they are organised.

Some of these problems will be temporary, but I worry there may be tension at the heart of this second kind of buy and build operation that does not exist in the Bunzl kind. The more autonomous businesses a company owns, the more can go wrong, which can increase the time and cost the head office spends managing them.

With that worry in mind, Page 17 of Cohort’s 2022 annual report caught my eye. It refers to the increasing cost of selling diverse military products and services to different countries, each with their own ways of doing business. Cohort says:

“The growth in central costs reflects the enhanced commercial, legal and financial resources we have brought in to support subsidiary growth, especially in export markets, together with the increasing compliance requirements faced by the Group.”

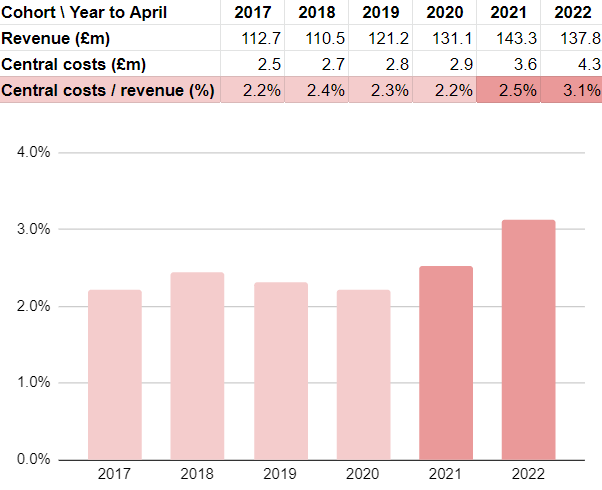

To quantify this growth in costs and determine its impact on Cohort’s profit margin, I have compared Cohort’s central costs to its turnover as disclosed in Cohort’s segmental reports:

The increase in costs is something to keep an eye on, but I do not think there is necessarily much to worry about. It amounts to about 1% of turnover, which is another way of saying that other things being equal Cohort’s profit margin, which averaged 11% (after tax) over the period and was 9% in 2022, is 1% lower because the company has a more expensive head office.

But an increase in central costs as a proportion of turnover is not what I would hope to see from a company growing in scale. With more businesses joining Cohort it ought to be able to make more efficient use of its central functions.

Cohort made its first overseas acquisition, EID, a Portuguese business, in its financial year ending in April 2017. It acquired Chess, an exporter in 2020, and ELAC, a German business in 2021.

This internationalisation required it to develop new capabilities to deal effectively with overseas subsidiaries and markets, but perhaps the growth in central costs will slow in future.

I hold shares in Cohort because I think it will be a profitable long-term investment and I have witnessed bigger businesses in different industries, like Judges Scientific and Halma, continue to make good profits as they have grown through buy and build strategies.

As they have grown, they too have bolstered their central functions to better coordinate the activities of their subsidiaries.

Another segmental story

I read segmental reports routinely. If the segments relate to separate businesses or very distinct activities, they can tell us more about what is going on in a company.

One thing that frustrates me, though, is that some companies only report the revenue of their segments or divisions, and not the costs or profit.

Recently, in a conversation with the finance director of a company that has a manufacturing segment and a distribution segment, I found out one reason why smaller companies do this.

While annual reports are mostly written for shareholders, anybody can read them including customers, competitors, employees, and suppliers. This means companies are often torn about how much information to disclose in them.

Let us say the company I am talking about only manufactured one type of product, a customer reading the annual report would know how much profit it was making and, if it were a lot, it would no doubt seek to pay less.

If all the customer has to go on is the combined profitability of the manufacturing division and the, say, less profitable distribution business then the negotiation is easier from our company’s point of view.

Fortunately for me, the company concerned has grown and now it manufactures many different products. It will be publishing the profitability of each division from next year. It feels comfortable doing this because it will not be giving away too much about the profitability of individual products.

The same finance director told me another story that reveals a similar but different tension in annual report writing.

I wanted to confirm my belief that the company is focusing on manufacturing semi-custom, as opposed to bespoke, products because introducing an element of standardisation is a way of reducing costs and increasing profit margins.

I accidentally called them semi-standard products, and he laughed. The company often debates whether to call the products semi-custom or semi-standard. Investors like semi-standard because it suggests they can be manufactured efficiently, but customers like semi-custom because it emphasises they are getting something special.

When a company writes its annual report it needs to consider everybody who might read it. Shareholders reading the annual report need to be aware of that too.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.