Investing in UK market-leading companies is a marmite proposition. They must have done something good but, if they are already so big, how can they keep taking market share? Richard examines market leaders Dunelm, and Inchcape (again!)

In this week’s update, only two companies published annual reports, passed my minimum quality filter and the 5 Strikes screening process by achieving less than three strikes.

They will be familiar to you.

The first was ‘Spoons, as my son calls it (JD Wetherspoon – Debt – ROCE) and the second was Dunelm. I’m going to skate straight past ‘Spoons because Dunelm has caught my eye.

Dunelm (- Debt)

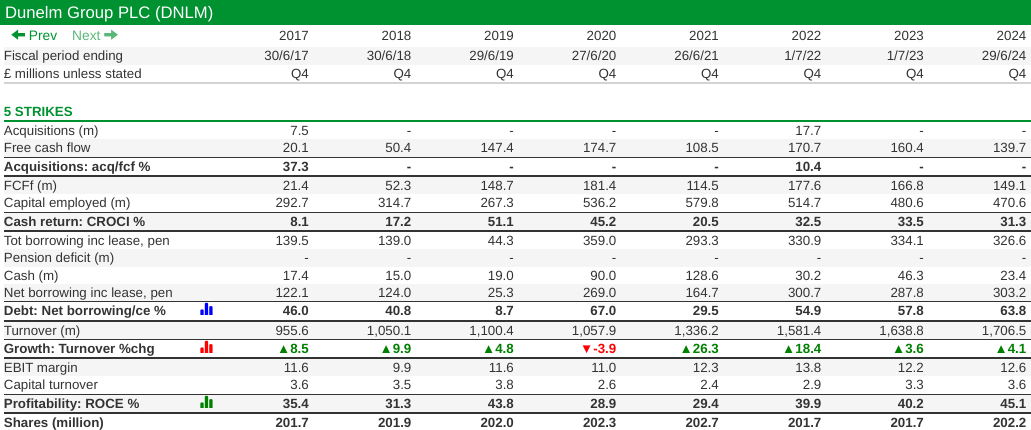

Furniture and homeware retailer Dunelm received only one strike, for debt. Otherwise, its track record (going back further than I can show on this page) is exemplary:

Source: Sharepad custom table (5 strikes)

Mostly the company has generated its own prosperity.

In December 2016, Dunelm acquired Worldstores out of administration. Dunelm was after the online home and garden retailer’s technical capabilities, delivery fleet, and Kiddicare brand which opened up a new category: Nursery.

The integration of loss-making Worldstores was partially responsible for Dunelm’s only year of single-digit Cash Return on Capital Invested in 2017.

Then, the company reported that its online business, responsible for 7% of revenue in 2016 and now incorporating Worldstores systems, would become Dunelm’s primary growth focus. In this year’s annual report, the company reported digital sales were 37% of the total.

Then, in May 2022, Dunlem acquired Sunflex, one of its main suppliers of curtain tracks, poles, and roman blinds, bringing specialist design capabilities and manufacturing in-house for one of its most popular product categories.

Since then, Dunelm has started manufacturing roller blinds and Venetian blinds at Sunflex, and it plans to launch in-house manufactured shutters in 2025.

These two small acquisitions may demonstrate a tendency towards vertical integration, which I think is encouraging.

Dunelm is the biggest furniture and homewares retailer in the UK, and perhaps its most specialised. Ikea is focused but international, and after that we have department stores like Next (fashion, furniture, homewares) and John Lewis, supermarkets like Asda and independent retailers.

Dunelm is using its resources to get better at supplying the UK public, whether that be through home delivery or by designing and making more appealing products at its relatively low price points. That focus differentiates it from many rivals whose resources are spread more thinly across other categories or overseas.

The company’s market share is a testimony to its past. It’s grown big by doing better than rivals.

There are limits because the UK is not that big of a market, but I am heartened by the fact that Dunelm’s market share is not that big. It’s 7.7%, which compared to some UK market leaders is quite modest (Pets at Home, I’m thinking of your market share of 24%). It has also grown revenue over the last two years, while the market has contracted.

Debt then, is the fly in the ointment, but I have been wondering about how big a fly it is. Most retailers use debt, as this selection of listed retailers that have a significant number of store shows. Dunelm is near the top of the list.

| TIDM | Name | Debt to Capital |

|---|---|---|

| WRKS | TheWorks.co.uk | 86.20% |

| BME | B&M | 68.80% |

| WIX | Wickes | 68.70% |

| SMWH | WH Smith | 68.50% |

| DNLM | Dunelm | 64.40% |

| TPT | Topps Tiles | 57.80% |

| NXT | Next | 46.60% |

| MMAG | Musicmagpie | 45.40% |

| HFD | Halfords | 35.20% |

| MKS | Marks & Spencer | 33.10% |

| CURY | Currys | 32.70% |

| FRAS | Frasers | 30.40% |

| CARD | Card Factory | 29.10% |

| BOO | Boohoo | 28.80% |

| SHOE | Shoe Zone | 28.60% |

| PETS | Pets at Home | 25.90% |

| HWDN | Howden Joinery | 24.60% |

| KGF | Kingfisher | 22.90% |

| JD. | JD Sports Fashion | 22.30% |

Source: SharePad. Debt to Capital is a combination of two SharePad items: Net borrowing “% of” capital employed. It includes pension deficits.

Debt in SharePad includes operating lease obligations in-line with accounting rules, so the indebtedness of the sector may reflect the fact that property companies often own retail parks and shopping centres. If retailers want to be present in these places, they may well have to rent.

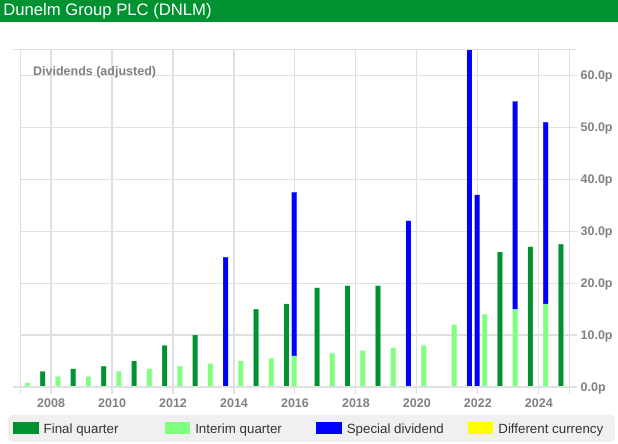

That said, debt is also a matter of choice at Dunelm. The company is highly cash-generative, so it could just hold surplus cash to offset its financial obligations if it was worried it might hit the buffers one year. Instead, it has been paying special dividends:

Source: SharePad > Financials > Dividends

No doubt Dunelm is confident it can carry substantial financial obligations and given its track record, it would be hard to argue with that.

For a company as self-sufficient as Dunelm, it may be irksome that landlords control the supply of stores.

The annual report says supply has contracted, and this year it bought a £22m freehold retail property to convert into a Dunelm superstore. Though it thinks the majority of stores will be leased in future, it’s open to buying more freeholds.

In terms of profitability and growth, Dunelm has a near-perfect record. Return on Capital is very high, typically 30% or more, and the company is a steady grower. Revenue only contracted once, in 2020, which coincided with the first locked-down months of the pandemic. It declined that year by less than 4%.

The share count is stable, and Sir Will Adderley, son of the founders, a former chief executive (twice) and current executive deputy chairman, owns 38% of the shares. Mum, Jean, still owns 5%.

The continuing influence of the founding family is probably one of the reasons the company embraces long-term thinking: “This means we take multi-year investment decisions, develop our future leaders and make meaningful choices as we strive to be good and circular”, the annual report says.

Inchcape: The complexity within

My enthusiasm for market leader Inchcape has run into a roadblock because I have been thinking about how it finances its business, the distribution of motor vehicles.

Inchcape describes itself as capital light, and its accounts show the strong cash flows and high returns (on modest capital employed) you would expect.

But Inchcape relies on lots of borrowed capital to fund the ownership of motor vehicles as it transports them from manufacturers to dealerships around the world, a journey that might typically take six months.

It relies on supplier credit, the fact that it does not have to pay manufacturers immediately, and inventory financing from banks. The split is about one-third supplier credit and two-thirds inventory financing.

Inventory financing is loans secured on the vehicles Inchcape owns. You might think that is a kind of debt, but it isn’t in terms of accounting (this is standard for motor distributors and dealerships).

Inventory financing falls under the category of “vehicle funding agreements”. These are liabilities recorded as trade payables, like the supplier credit, rather than borrowings on the balance sheet.

This improves Return on Capital because, typically investors treat payables as other people’s capital (aka interest-free loans) and deduct them from Capital Employed, unlike debt which is included in ROCE.

Vehicle funding agreements totalled nearly £1.9 billion in 2024.

To put that figure in perspective, if we were to treat the vehicle funding agreements like other kinds of borrowing, Inchcape’s financial obligations would almost double and its debt-to-capital ratio at the end of 2024 would have been 67%, instead of the relatively modest 30% calculated by SharePad.

Return on Capital in 2024 would have been 11.5% (based on reported rather than adjusted profit) instead of SharePad’s 16% figure.

So why? Why are vehicle finance agreements not treated the same as conventional borrowing? I think this is because the vehicle funding agreements are designed to mimic supplier credit.

An interested reader (CE – thank you) tells me this has been normal since GM invented inventory financing a century or more ago.

Inchcape expects to sell vehicles before the financing runs out. It makes sure the margin it earns is sufficient to pay the interest, which Inchcape considers to be another cost it passes through to dealerships, and still profits.

The risk is that it doesn’t sell the vehicle in time to pay off the loan, in other words, it miscalculates.

I imagine there are lots of options open to Inchcape in that scenario. It can discount vehicles even if it means losing money. Ultimately it can hand vehicles over to the bank, although that would surely compromise its ability to raise finance in future.

The risk does not appear to be too great. Every year Inchcape writes off some of the value of its stock, but this increased only slightly in 2020 when the pandemic must have played havoc with its forecasts.

Forecasting demand, pricing vehicles and managing inventory are in a sense, Inchcape’s business. Part of me wants to trust the company to do this well, and the consensus that there is nothing much to worry about.

But another part of me hates financial complexity.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net, Twitter: @RichardBeddard, web: beddard.net

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Richard? Share these in the Sharescope chat. Login to Sharescope – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.