Poor record-keeping at a small subsidiary prompted an adverse audit at Victoria last year. Maynard Paton looks at other areas of the carpet manufacturer’s accounts in which the auditor identified ‘material errors’.

Oh dear. Today I am writing about Victoria, a £228 million carpet manufacturer that last year attracted attention following an adverse audit.

When I last looked at an adverse audit for SharePad, a commotion erupted that debated whether I was simply reporting “transcription errors” or spotlighting something more sinister.

So to be clear:

- What follows is just my interpretation from reading Victoria’s 2023 annual report and other company statements;

- I have not inspected every part of Victoria’s accounts nor considered every aspect of the wider investment case, and;

- Please do your own research and form your own conclusion.

And with that, let’s take a closer look.

Introducing Victoria

Victoria was established during 1895, joined the stock market in 1963 and led a somewhat unremarkable corporate life until 2012.

That year witnessed a boardroom tussle as the then directors tried to fend off unhappy shareholders agitating for fresh leadership and greater ambition.

A series of board reshuffles were eventually resolved with the appointment of a new executive chairman, who then set in motion an extraordinary business transformation.

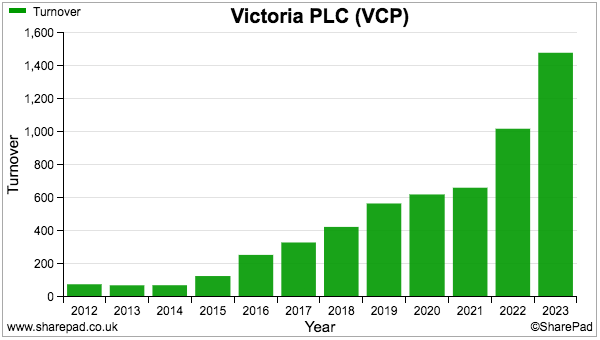

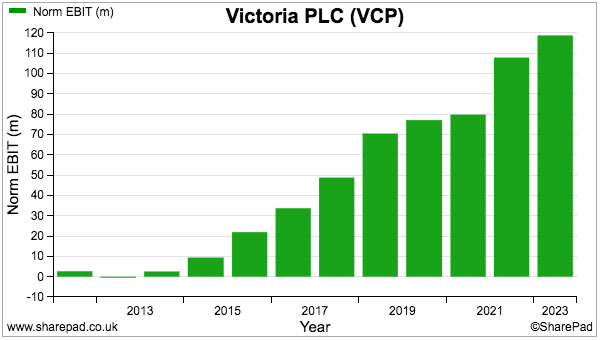

A buy-and-build strategy was employed, with £800 million or so spent on at least 20 acquisitions that turned revenue of £70 million into £1.4 billion…

…and underlying profit of £3 million into £119 million:

The share price reacted accordingly, with 20-bagger returns available for anyone buying during 2012 and exiting at the £12 top:

But the buy-and-build approach has since faltered due to weaker trading, lower margins, rising debt costs and, most interestingly, accounting concerns following an adverse audit.

Adverse audit

Victoria’s adverse audit emerged last summer. The group had scheduled its 2023 results for 15 August, but on the day had to admit the auditors had “requested further time to complete their final audit procedures“.

The results were published on 14 September and the full annual report was published on 29 September. The auditor’s review “identified potential irregularities” within the group’s Hanover Flooring subsidiary:

“We selected some non-significant components, including Hanover Flooring Limited (‘Hanover’), to incorporate unpredictability into our audit approach… In the course of our audit work, we identified potential irregularities in respect of certain transactions within Hanover…”

With revenue of £19 million, Hanover was a small operation within the wider group’s sales of £1.4 billion. But the auditor nonetheless requested to delve deeper into Hanover’s books:

“This work, and the procedures we have performed in response, has not adequately addressed our concerns. We sought to obtain further evidence but were unable to do so because management imposed a limitation of our scope. We requested that the Board remove management’s limitation, which they did not.“

Management refused the request to delve deeper because the extra work was not expected to yield “better-quality evidence“:

“Because of [the Board’s] view that our proposed procedures are unlikely to generate further or better-quality evidence to address our concerns, the Board has prevented us from undertaking further work in the area.”

The auditor therefore had to issue a qualified opinion on the 2023 accounts and could not rule out “material fraud or error” at the problem subsidiary:

“We were therefore unable to reduce the risk of material fraud or error to an acceptable level and obtain sufficient and appropriate audit evidence for all Hanover balances (net liabilities of £0.4m, 2022: net assets of £0.7m) and transactions (including revenue, loss before taxation and underlying profit before taxation of £18.7m (2022:£23.4m), £1.2m (2022: £0.9m) and £3.9m (2022: £5.8m) respectively) and cannot conclude whether any irregularities have or have not taken place, other than those disclosed by management on pages 29-30.”

Victoria’s AGM statement on 29th September brushed aside the “considerable reaction” to what management described as a minor record-keeping issue:

“However, over this last week, the strong outlook for Victoria has been overshadowed by the considerable reaction to our auditor’s qualified opinion deriving from incomplete accounting records at a small subsidiary, Hanover Flooring Limited – a business which as a whole represents less than 1.25% of Group turnover.

The Board wishes to stress that there was no wrongdoing whatsoever at Hanover that impacts the Group’s financial statements and nor are the auditors alleging this. Hanover’s issue was predominantly one of having heightened financial risk due to inadequate accounting records associated with no more than £400,000 of customer receipts.”

The “considerable reaction” included commentary from the Financial Times (Victoria plc’s audit nightmare) and anonymous blogger Brevarthan Research (Victoria plc: questions for the auditors and the follow-up Victoria plc: company responses). Both publications have noted the ‘colourful’ background of the previous owners of the problem subsidiary.

But the “inadequate accounting” at Hanover was not the only awkward discovery within Victoria’s 2023 audit.

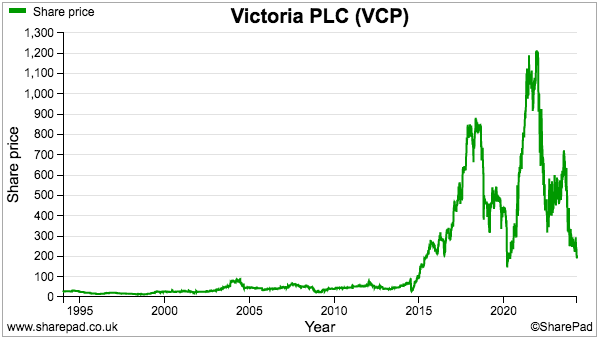

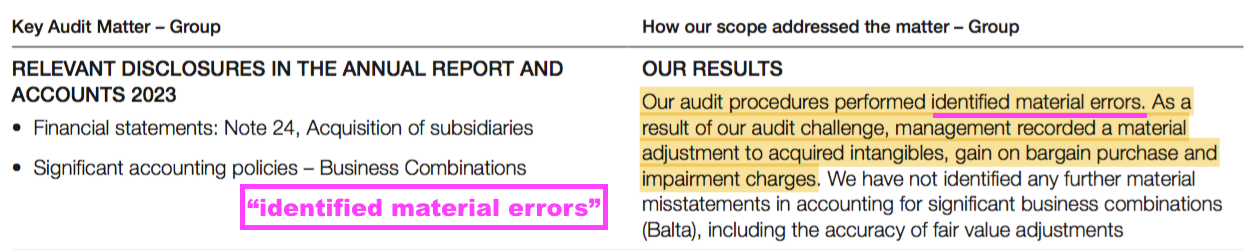

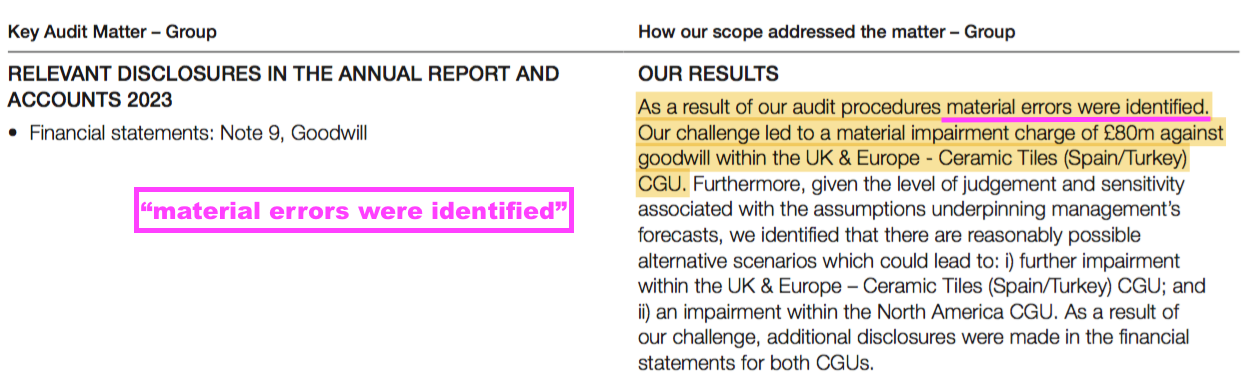

The auditor also unearthed “material errors” when assessing the intangibles acquired through the purchase of Belgian rugs manufacturer Balta…

…as well, further “material errors” when evaluating the value of goodwill created through earlier purchases of certain ceramic-tile businesses:

Although corrected before the publication of the 2023 results, these “material errors” do not suggest first-class bookkeeping and give curious observers further reason to study the accounts.

Negative goodwill

The “material errors” relating to the purchase of Balta highlight the accounting concept of ‘negative goodwill’, which arises when companies are acquired for less than their ‘fair value’.

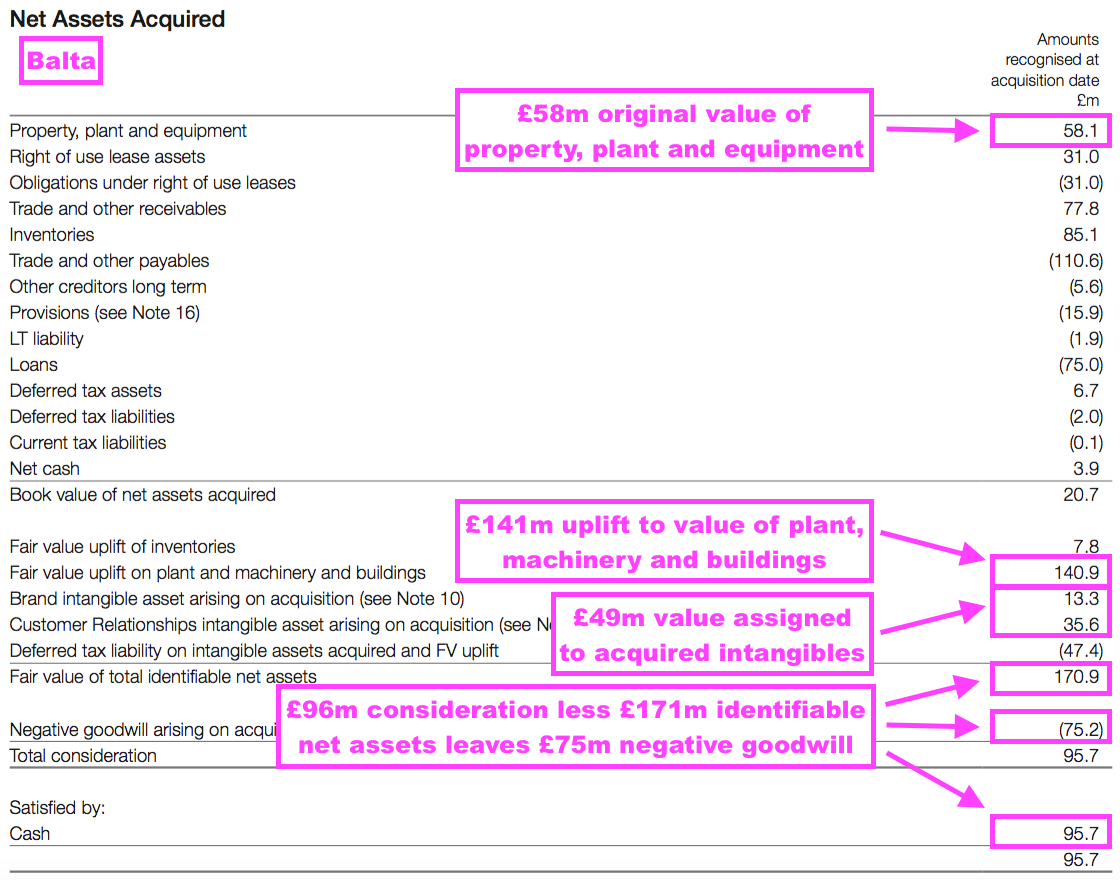

The 2023 annual report shows Victoria paid £96 million for Balta’s identifiable net assets of £171 million that created negative goodwill of £75 million:

The identifiable net assets of £171 million consisted of net assets of £21 million plus Victoria assigning a net ‘fair-value uplift’ to those net assets of £150 million.

That £150 million uplift included £49 million (before deferred tax) associated with the acquired intangibles.

The auditor’s text — “As a result of our audit challenge, management recorded a material adjustment to acquired intangibles, gain on bargain purchase and impairment charges” — implies the £49 million uplift was somewhat higher before the auditor questioned Victoria’s calculation.

The Balta footnotes also include a £141 million uplift to the fair value of the plant, machinery and buildings acquired…

…which seems a remarkable gain given property, plant and equipment was attributed with an initial £58 million book value.

Victoria implied the £141 million uplift was due to a desperate seller:

“The favourable uplift on plant and machinery acquired which was not fully taken into account by the vendor who was seeking a relatively quickly sale and exit from the business was the primary cause of negative goodwill.”

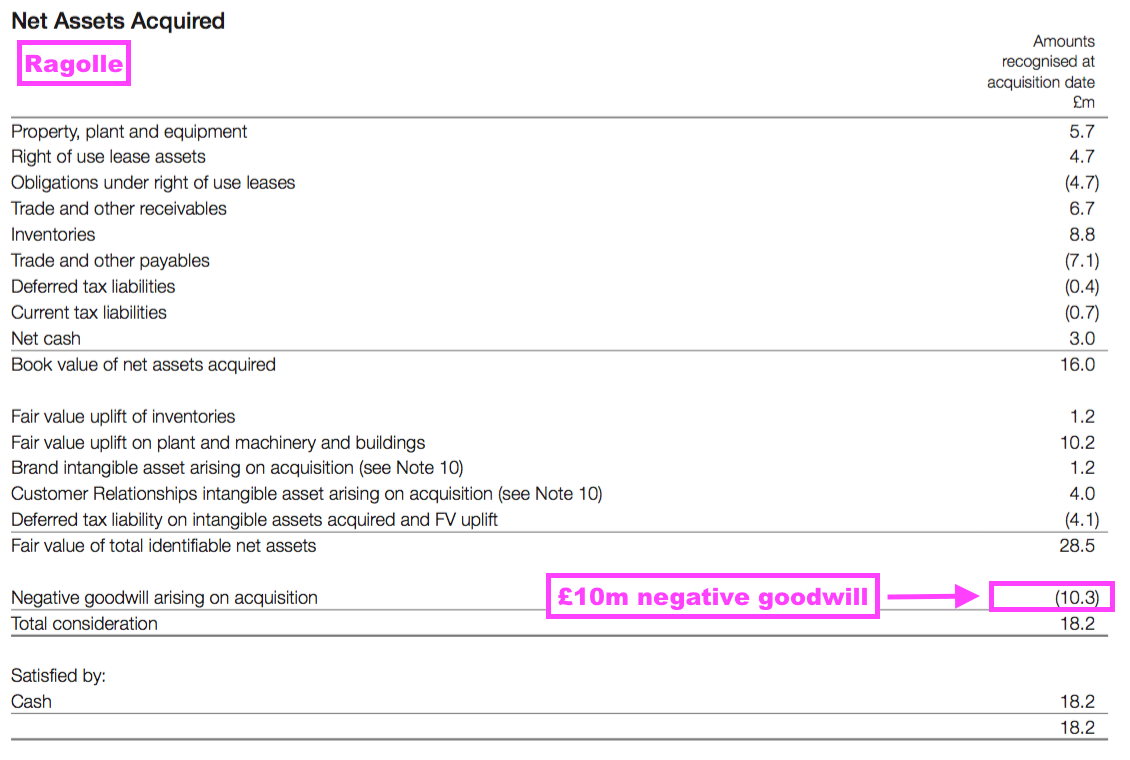

Negative goodwill also featured at Victoria’s two other acquisitions for 2023.

Ragolle, another Belgian rug manufacturer, was acquired for £18 million and generated negative goodwill of £10 million:

Ragolle was also acquired from a desperate seller:

“The favourable uplift on plant and machinery acquired which was not fully taken into account by the vendor who was seeking a relatively quickly sale and exit from the business was the primary cause of negative goodwill.”

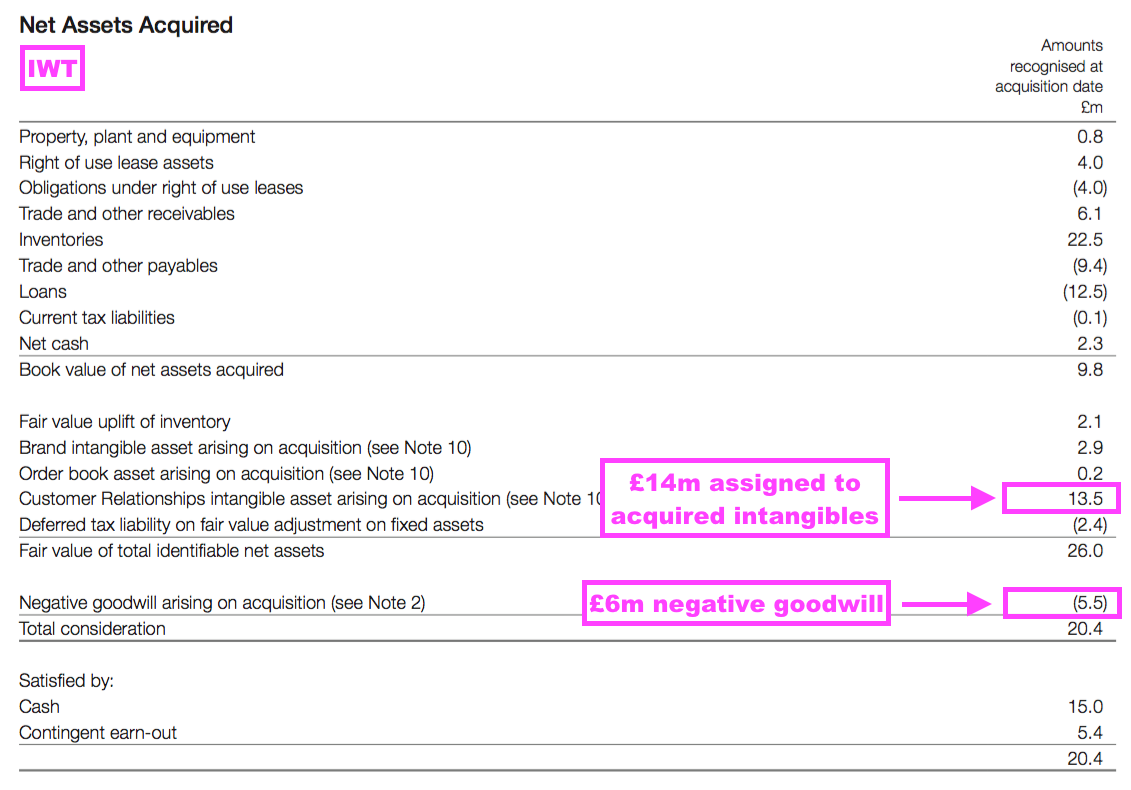

And International Wholesale Tile (IWT), an American flooring distributor, was acquired for £20 million and generated negative goodwill of £6 million:

Victoria argued that IWT’s negative goodwill was created by including the full earn-out in the purchase price:

“The main driver of the negative goodwill is the accounting treatment of the earn out liability, with amounts contingent on service conditions accounted for as accrued employment costs (recognised over time post-acquisition) despite the full earn out being included in the structure of the overall purchase price as stipulated in the share purchase agreement.”

However, the accounts suggested IWT’s negative goodwill was more to do with the £14 million value attributed to the acquired ‘customer relationships’.

Just to be clear, fair-value uplifts and negative goodwill are legitimate accounting concepts and Victoria’s auditor approved all of the above figures.

Victoria also noted the extra £141 million uplift to Balta’s plant, machinery and buildings was subsequently reduced following a restructure:

“Operational decisions made after the [Balta] acquisition, that were also considered as part of the consideration paid, has meant that the full fair value uplift was never fully utilised hence there was a later impairment and significant associated restructuring costs have been incurred within FY23.”

Nevertheless, the presence of “material errors” within the fair-value uplifts before the auditor intervened…

…as well as the suggestion that plant, machinery and buildings of £58 million were actually worth a further £141 million…

…it does make you wonder about optimistic assumptions being applied elsewhere in the accounts.

What is not in doubt is the creation of negative goodwill adds another accounting entry to Victoria’s long list of exceptional and non-underlying items.

Exceptional and non-underlying items

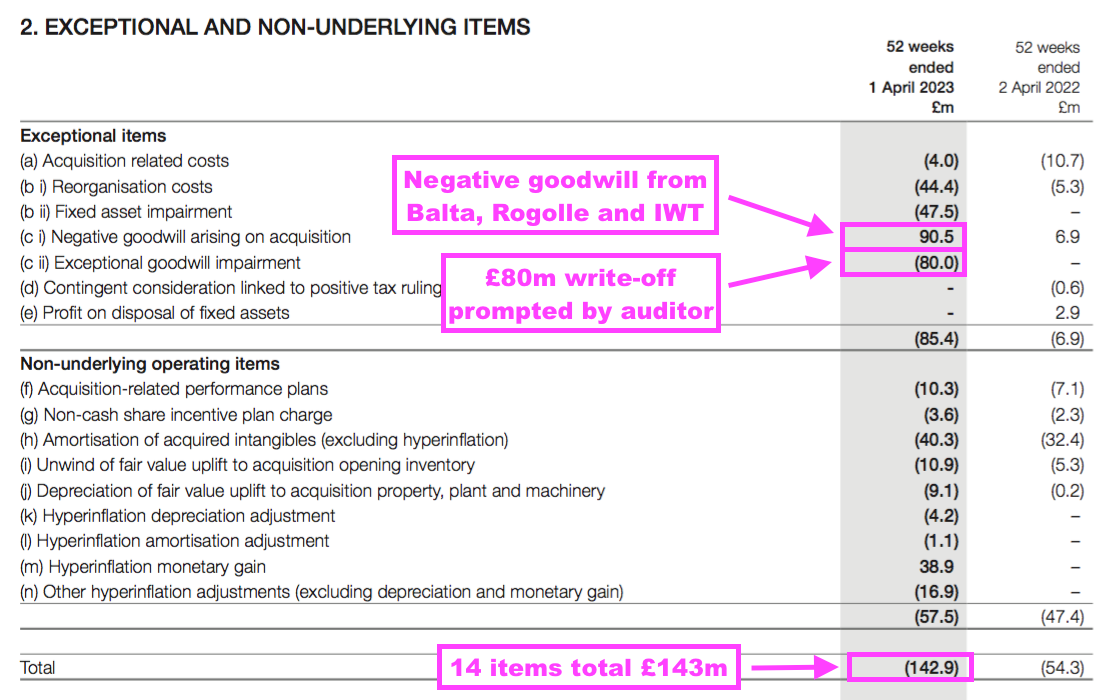

Victoria’s 2023 annual report disclosed 14 separate exceptional and non-underlying items:

Just so you know, the group’s exceptional items relate entirely to third-party ‘one off’ expenditure while the non-underlying items are (typically) non-cash charges that are deemed “not to fairly represent the underlying business” and may be repeated from year to year.

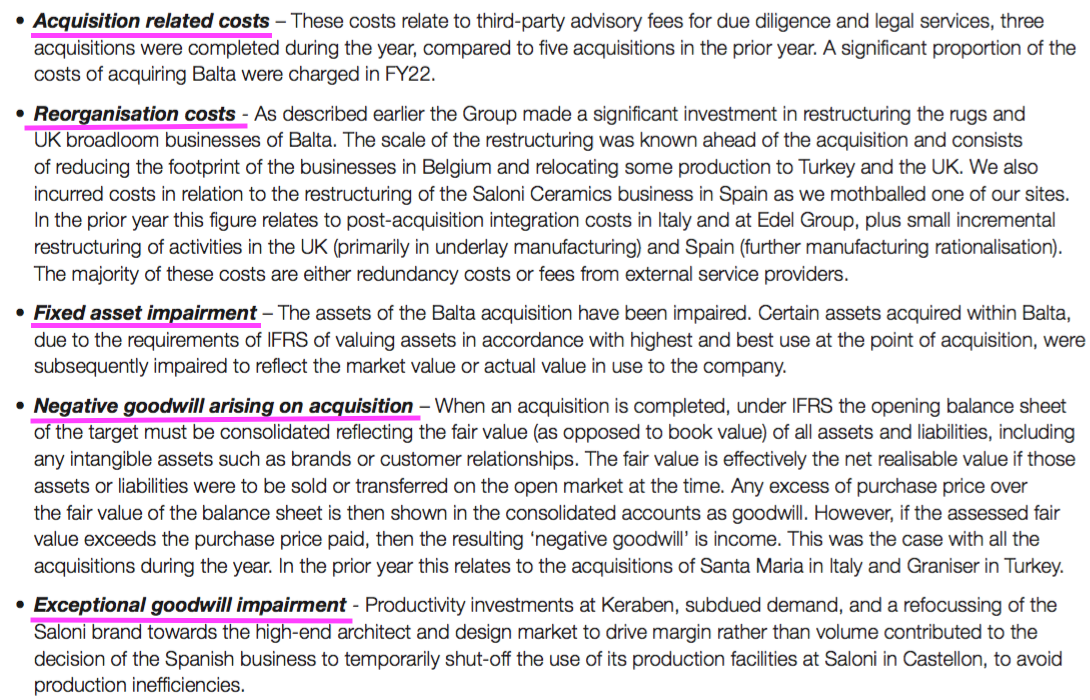

Included in the 2023 list was the negative goodwill from Balta, Ragolle and ITW of £91 million.

Also included was the £80 million goodwill write-down associated with certain ceramic-tile businesses that was prompted by the auditor after the discovery of additional “material errors“.

I have to confess, the auditor’s text — “Our challenge led to a material impairment charge of £80m against goodwill” — does not give the impression of prudent bookkeeping and again makes you wonder whether optimistic assumptions are applied elsewhere in the accounts.

Anyway, each exceptional and non-underlying item could individually be argued as genuine, and Victoria does describe each entry:

For example, Victoria deeming the amortisation of acquired intangibles as non-underlying is in keeping with the vast majority of quoted companies. Gains through hyperinflation in Turkey also seem unusual and worth excluding from the underlying figures.

But the size and frequency of Victoria’s exceptional and non-underlying items are significant.

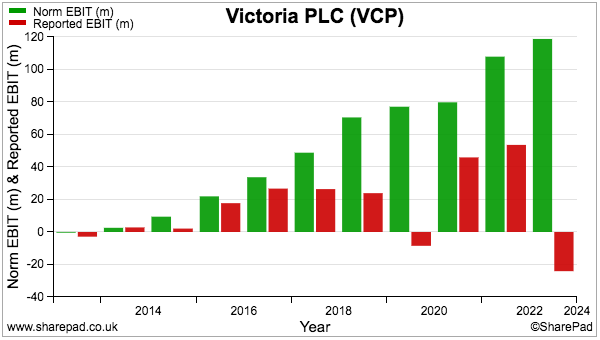

SharePad shows Victoria registering an aggregate operating profit before exceptional and non-underlying items (green bars) of £567 million during the last ten years:

In contrast, the aggregate ten-year operating profit after exceptional and non-underlying items (red bars) is £167 million.

Just to be clear, Victoria’s auditor has not quibbled with the exceptional and non-underlying items within the 2023 annual report.

But the cumulative difference between the ‘underlying’ and statutory operating profit during the last ten years — a mighty £400 million — ought to prompt curious observers to interpret the numerous adjustments.

Indeed, should the £109 million charged since 2014 as ‘exceptional’ acquisition and reorganisation costs be instead viewed as ‘normal’ expenditure of a buy-and-build operator?

And should shareholders simply ignore both the aforementioned £80 million goodwill write-off and an earlier £50 million goodwill write-off — essentially an admission of Victoria overpaying for businesses by £130 million?

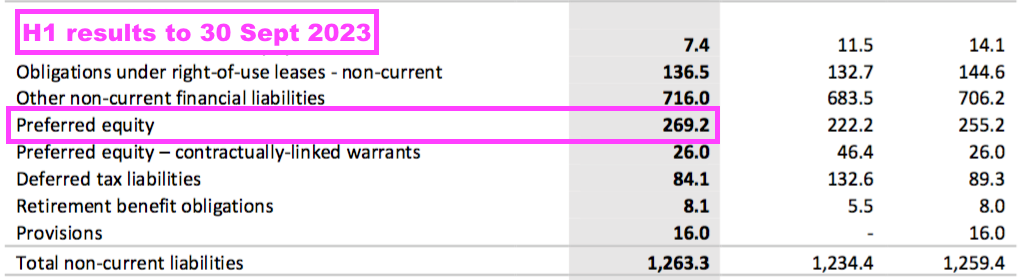

The non-underlying items do not stop at the operating level. Finance costs also include several non-underlying items — the most conspicuous of which relate to Victoria’s preferred equity:

Victoria’s preferred equity may even surpass the adverse audit on the list of shareholder concerns.

Preferred Equity

To help fund its acquisitions, Victoria raised £225 million between 2020 and 2022 through the issue of preferred equity.

To service this preferred equity, the group can either:

- Pay a cash dividend equivalent to 8.35% of the preferred shares, or;

- Make a ‘payment in kind’ equivalent to 8.85% of the preferred shares by issuing additional preferred shares.

To date, Victoria has never paid a cash dividend on the preferred equity and, at the last count, the outstanding amount had increased to £269 million:

What look to be the accrued ‘payment in kind’ dividends of £44 million (£269 million less the original £225 million) have been defined as ‘non-underlying’. Victoria explains:

“Given the [preferred equity] instrument is legally equity capital and equity-like in nature as the preferred shares are perpetual, and there is no obligation to ever cash settle any of the preferred dividends, any ongoing financial costs in respect of this facility are not considered to form part of the underlying performance of the business.”

However, at some point, the holders of the preferred equity will surely demand a cash return on their £225 million investment. And without Victoria paying preferred cash dividends, the only sure way the preferred holders can eventually extract a cash return is through an equity conversion.

The 2023 annual report outlines the preferred equity’s conversion process:

“After the sixth anniversary, [Koch Equity Development] can elect to convert the outstanding preferred equity and [accrued payment-in-kind] dividends into ordinary shares, with the conversion price being the prevailing 30 business day [volume-weighted average price] of the Company’s ordinary shares.”

Circulars on Victoria’s website (here and here) confirm:

- The sixth anniversary occurs during November 2026, and;

- There is no maximum nor minimum limit to the number of shares that can be issued to satisfy the conversion.

During November 2020 when the preferred equity was first issued, Victoria’s shares traded between 400p and 600p and adjusted EBITDA was approximately £112 million. Management then talked of the share price being “materially higher in six years’ time” and acquiring extra EBITDA of £100 million:

“Koch has the right after six years to convert their preferred shares into ordinary shares at the share price at that time. It is the Board’s belief that Victoria’s share price will be very materially higher in six years’ time (not least because of the £100 million of EBITDA that the preferred equity capital could allow us to acquire), and this will reduce the number of ordinary shares that Koch will receive if they convert.”

Subsequent events have so far not quite worked out as Victoria expected. The shares now trade around 200p and the group’s latest EBITDA forecast of £160 million indicates the preferred equity has (at most) generated extra EBITDA of only £48 million.

The concern with the lower 200p share price is the potential dilution Victoria’s shareholders could face from November 2026.

Assuming another two years of payment-in-kind dividends and no share-price recovery, the outstanding preferred equity could top £300 million and therefore convert into approximately 150 million new ordinary shares.

Victoria’s current share count is 114 million, meaning existing shareholders may be diluted by more than 50% should the preferred equity convert on those assumptions.

Making matters worse is the lack of any limit to the number of ordinary shares into which the preferred equity can convert.

An outside risk therefore is a vicious circle of the share price falling because of the perceived risk of significant dilution from a preferred equity conversion…

…which then in turn increases the risk of greater dilution because of the falling share price!

For what it is worth, the 2023 annual report assumes the preference shares will not be converted into ordinary shares:

“The [Koch Equity Development] option to convert into ordinary shares: The model uses standard option pricing techniques to calculate the optimal time to exercise the respective options. As such, the valuation technique assumes that all interest will be accrued and rolled into the preference share balance and that there will be no conversion of the preference shares into ordinary shares due to their coupon and enhanced liquidity preference. As a result, nil value has been attributed to this feature.”

Bank debt, buybacks and forecasts

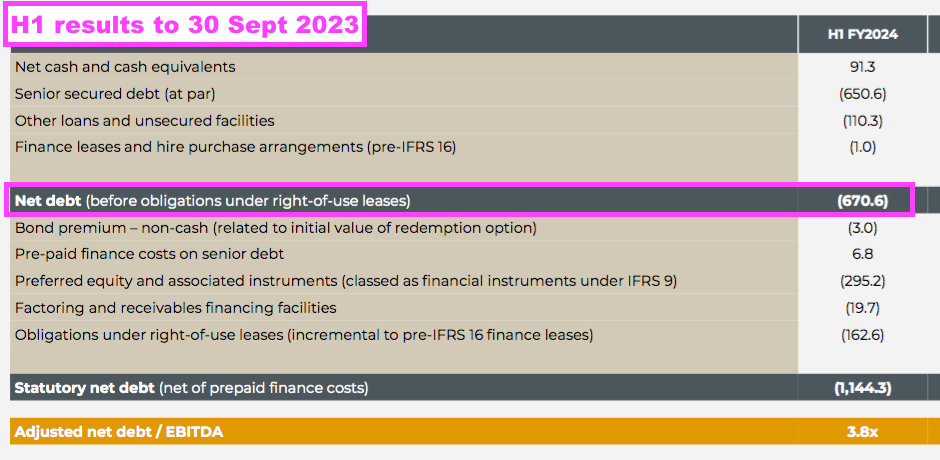

Preferred equity is not the largest liability on Victoria’s balance sheet. Net bank debt at the last count was £671 million:

Annual interest on the bank debt currently runs at approximately £34 million, which is substantial for a business that last year reported an operating profit (before exceptional and non-underlying items!) of £119 million.

An update on 13 March declared “de-leveraging remains a key target for the Board” and revealed the €11 million repurchase of loans due for refinancing during 2026.

These 2026 loans were issued during 2021, amounted to €500 million and presently attract interest at 3.625% — a cost that seems almost certain to increase post-refinancing given the end of ultra-low base rates.

The March update also noted disposals of non-core assets should raise €81 million with a further £30 million extracted through tighter stock control during 2025. The race therefore seems on to raise money and reduce debt before the 2026 refinancing imposes higher borrowing costs.

Mind you, the March update also announced a share buyback of up to £25 million due to the share price being “materially below the intrinsic value of the Group”:

“It is the Board’s intention to invest up to £25 million in the repurchase of shares, subject to certain conditions and the ratio of price to intrinsic value remaining highly attractive, whilst protecting the Group’s cash position and liquidity. The Board believes the current share price is materially below the intrinsic value of the Group…“

Whether buybacks are a prudent use of cash when “de-leveraging remains a key target for the Board” is debatable.

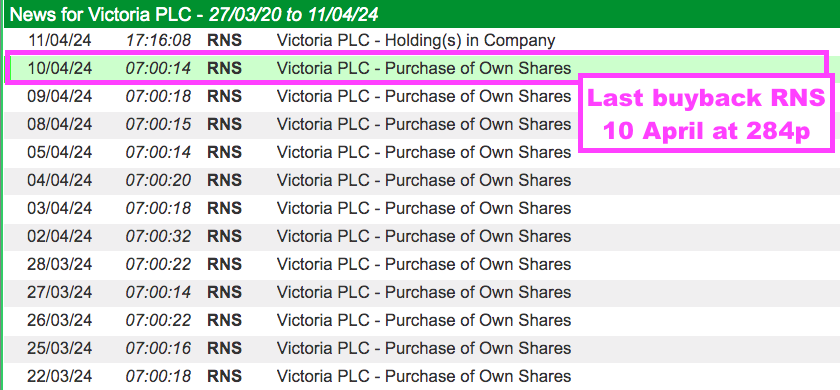

To date, Victoria has spent £4 million on buying shares at an average 243p, and was quite happy paying up to 284p but has not bought when the shares recently touched 200p:

For extra perspective, an £8 million buyback undertaken during 2022/3 was conducted at an approximate 420p average while a £30 million buyback undertaken during 2017/8 was conducted at a 350p average.

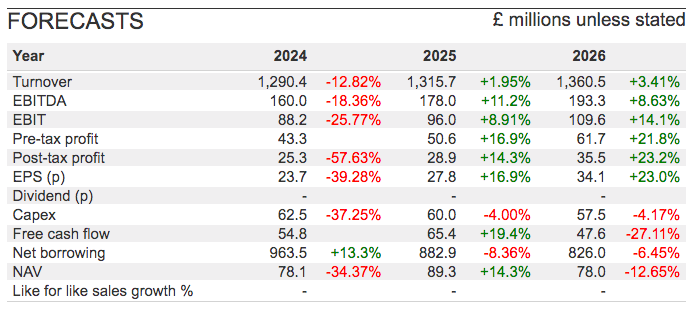

Brokers have interpreted March’s update into the following SharePad forecasts:

Small revenue advances plus margin improvements are expected to reverse the 2024 profit shortfall during 2025 and 2026, although net debt — which on SharePad includes the preferred equity — does not show major reductions.

Victoria’s ‘noise’

March’s update stated:

“There has been a lot of noise around Victoria in the last six months.”

The ‘noise’ has actually been growing for some time. In particular, Iceberg Research had commendably identified issues with the problem Hanover subsidiary during 2022 while George Soros was shorting the shares back in 2018.

No doubt I am adding to the ‘noise’, but I can’t help but feel something is not quite right.

I must mention the 2023 audit introduced a new key audit matter that double-checked Victoria’s ‘going concern’ assumption:

“Due to recent macro-economic factors such as high inflation, deflated growth expectations and reduced customer confidence and declining margins and subdued revenue growth in the year, we have judged that there is a significant risk to the Group that the going concern assumption adopted in the preparation of the financial statements may be impacted.”

A ‘going concern’ key audit matter is not very common, and the auditor essentially questioned whether Victoria did indeed have the “sufficient resources available to meet its liabilities as they fall due“.

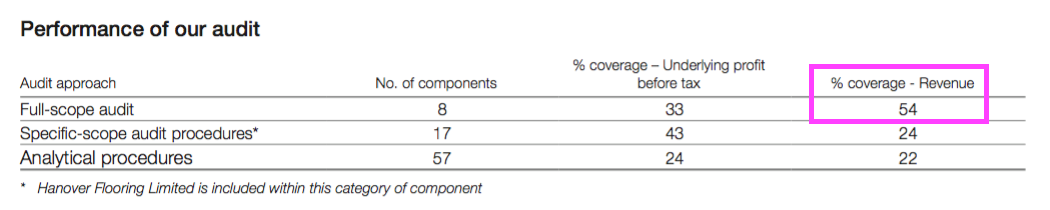

I would also highlight how full-scope audits were performed on operations representing only 54% of 2023 revenue:

The full-scope percentages for the previous five years were:

- 2022: 64% of revenue;

- 2021: 70% of revenue;

- 2020: 81% of revenue;

- 2019: 89% of revenue, and;

- 2018: 92% of revenue.

The lower proportion of revenue assessed through full-scope audits implies the auditor has been delving deeper into fewer parts of the group.

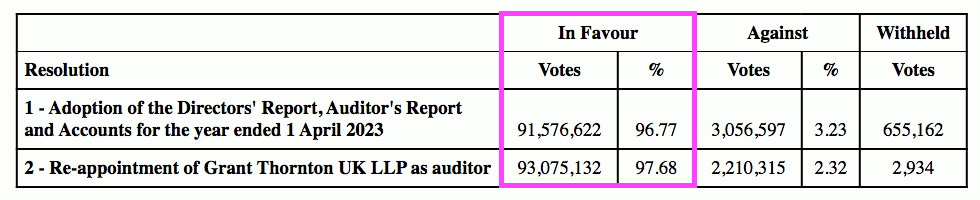

Still, existing shareholders seem very relaxed about the 2023 audit after approving the annual report and the auditor’s reappointment with a 96%-plus landslide:

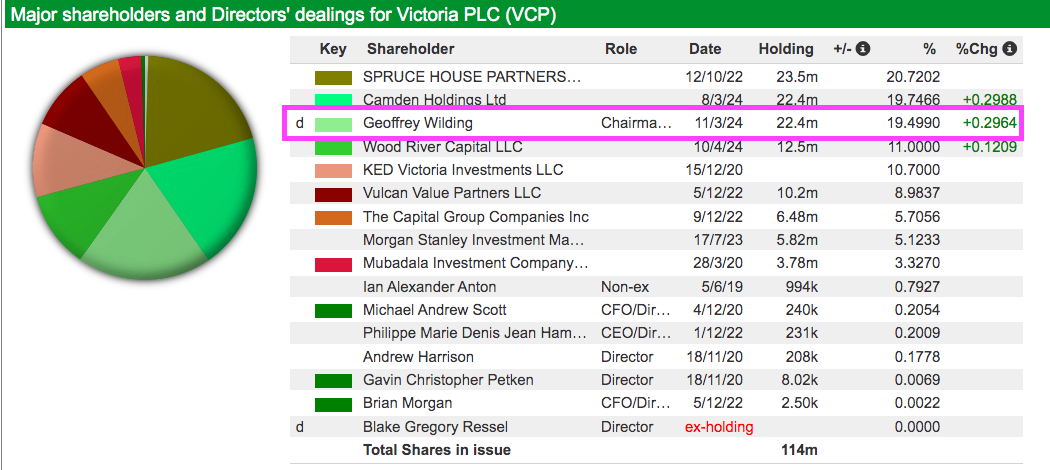

Furthermore, the executive chairman that led the group’s transformation remains in charge and boasts a 19%/£45 million shareholding that ought to encourage keeping the accounts in good shape:

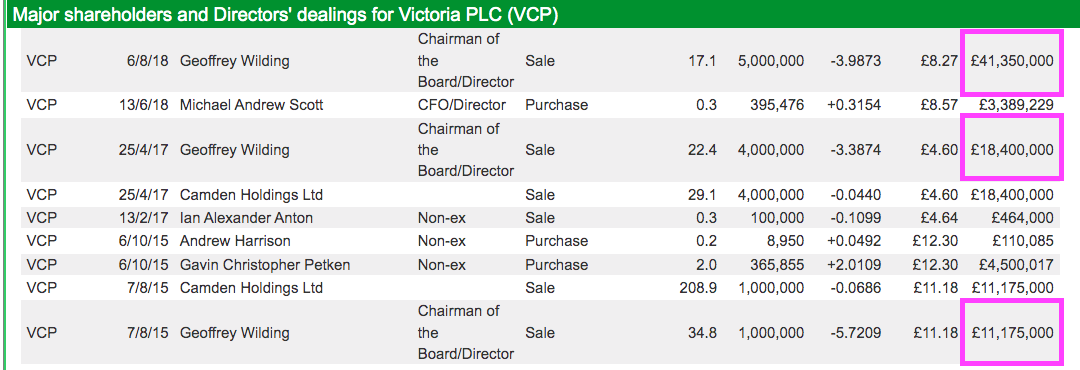

The chairman did raise approximately £70 million from share sales between 2015 and 2018…

…. and I would venture reinvesting a chunk of that £70 million back into Victoria — after all, the board believes the shares are “materially below the intrinsic value of the Group” — would appear the best way to curtail further ‘noise’ about the adverse audit.

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Maynard writes about his portfolio at maynardpaton.com. He does not own shares in Victoria.

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Maynard? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.