Phil looks at the issues with one of the most important ratios in investing and argues the case for a cleaner and more realistic alternative.

Return on investment or return on capital employed (ROCE) as it is commonly referred to is seen as one of the best measures of a company’s financial performance.

It is also one of the better ways of comparing the performance of two similar companies to try and work out which might be the better investment.

ROCE tries to measure what a company gets back in profit as a percentage of the amount of money it has invested in the business (capital employed).

This should be relatively straightforward for an investor to calculate but as with many things in investing, it can get complicated and you need to be aware of things that can influence the results you can get from it.

The basic calculation

A generally accepted way of calculating ROCE – and the way SharePad calculates it – is to divide a company’s earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) by the capital employed.

ROCE = EBIT/Capital Employed

EBIT is easy to find on a company’s income statement.

Most investors start with a company’s adjusted operating profit figure which strips out one-off gains and losses to give a measure of the underlying trading profits.

The profits from joint ventures (JVs) and associates – the profits from businesses that are not entirely owned by the company – are then added to this figure to get EBIT.

EBIT = Adjusted operating profits + profits from JVs and associates

Capital employed can be calculated from either the asset side or liability side of the balance sheet.

From the asset side, you take the figure for total assets and subtract non-interest-bearing current liabilities. The easiest way to do this is to subtract all current liabilities and then add back short-term borrowings including lease debt.

Alternatively, you can use the numbers from the liability side of the balance sheet by adding together total equity, total borrowings (current and noncurrent) and all other non-current liabilities. You will get the same number.

Many investors will then calculate the average capital employed to limit the distortions of big numbers that are recorded on the balance sheet near a year end. To calculate average capital employed, simply make the calculation for one year and the previous year and divide by two.

So:

ROCE = EBIT/Average Capital Employed

Calculating Unilever’s ROCE

Taking numbers from Unilever’s 2022 annual report, we can calculate its ROCE which is a pretty decent 17.2 per cent.

|

€m |

2022 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|

|

EBIT(A) |

9891 |

|

|

Total Assets |

77821 |

75095 |

|

Current Liabilities |

-25427 |

-24778 |

|

Short term debt |

5571 |

7061 |

|

Capital Employed |

57965 |

57378 |

|

Average Capital Employed(B) |

57672 |

|

|

ROCE=A/B |

17.2% |

Source: Annual Reports

As with any ratio, one single number does not tell us that much. It is much better to look at the trend in the number and perhaps compare it with a business in the same sector.

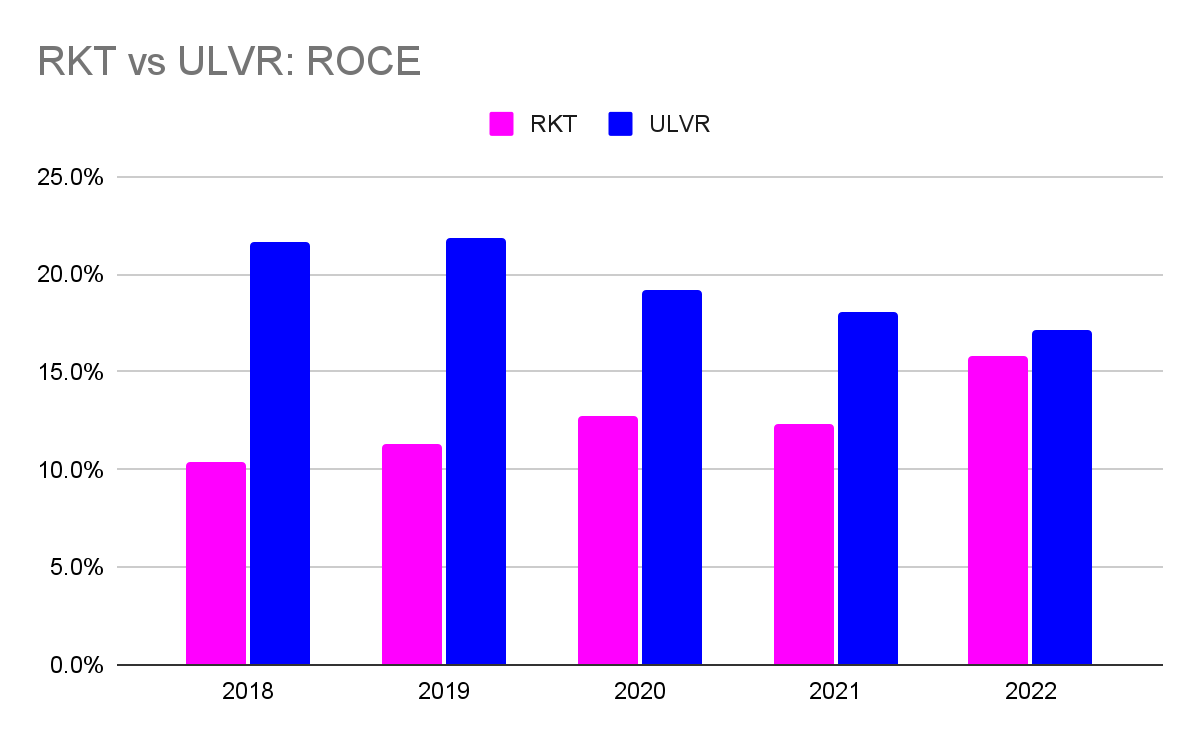

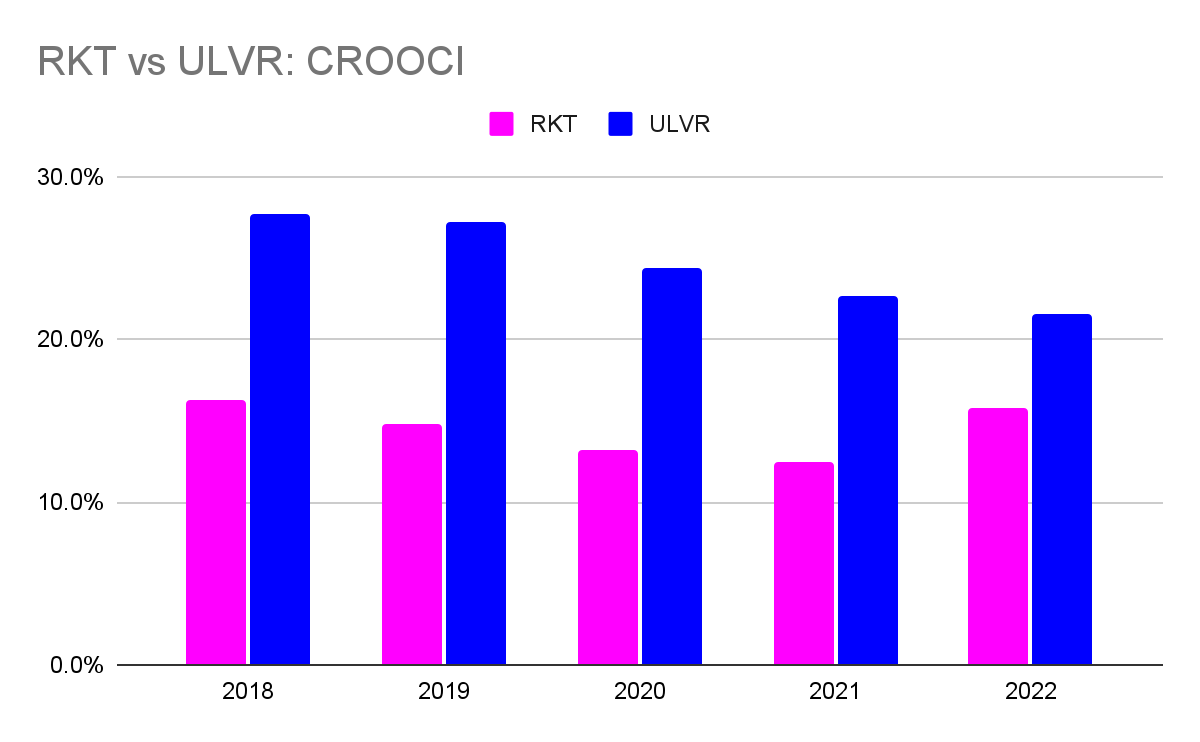

Here, we look at Unilever’s trend in ROCE between 2018 and 2022 and compare it with Reckitt Benckiser’s.

The comparison is done on the same basis using numbers from annual reports.

SharePad calculates ROCE using normalised EBIT numbers which come from its data provider. That’s fine, but the key is to be consistent with the calculation over time.

Source: Annual Reports

We can see here that Unilever’s ROCE has been on a declining trend, whereas Reckitt Benckiser’s has been moving up.

Unilever is still more profitable but Reckitt has closed the gap. Both companies’ ROCE would indicate that they are very good businesses.

Some investors might calculate ROCE in this way and leave it at that. But is this calculation the right one to focus on?

ROCE and goodwill

Companies can create assets by developing themselves or they can acquire them by buying another company.

When a company buys another company it often pays more for its assets than the value on the balance sheet. The amount of money above the balance sheet value is known as goodwill.

This goodwill is a separately disclosed number on the acquiring company’s balance sheet and can be a big number if it has made lots of acquisitions in the past.

The important point to take on board is that goodwill is part of capital employed and is included in the ROCE calculation above.

Whilst it is always good to look at the returns a company is achieving on all the money it invests, the standard ROCE calculation can sometimes mask the profitability of a company’s operating assets.

Goodwill reduces ROCE – sometimes by significant amounts – but this can sometimes lead to investors missing out on identifying very profitable businesses.

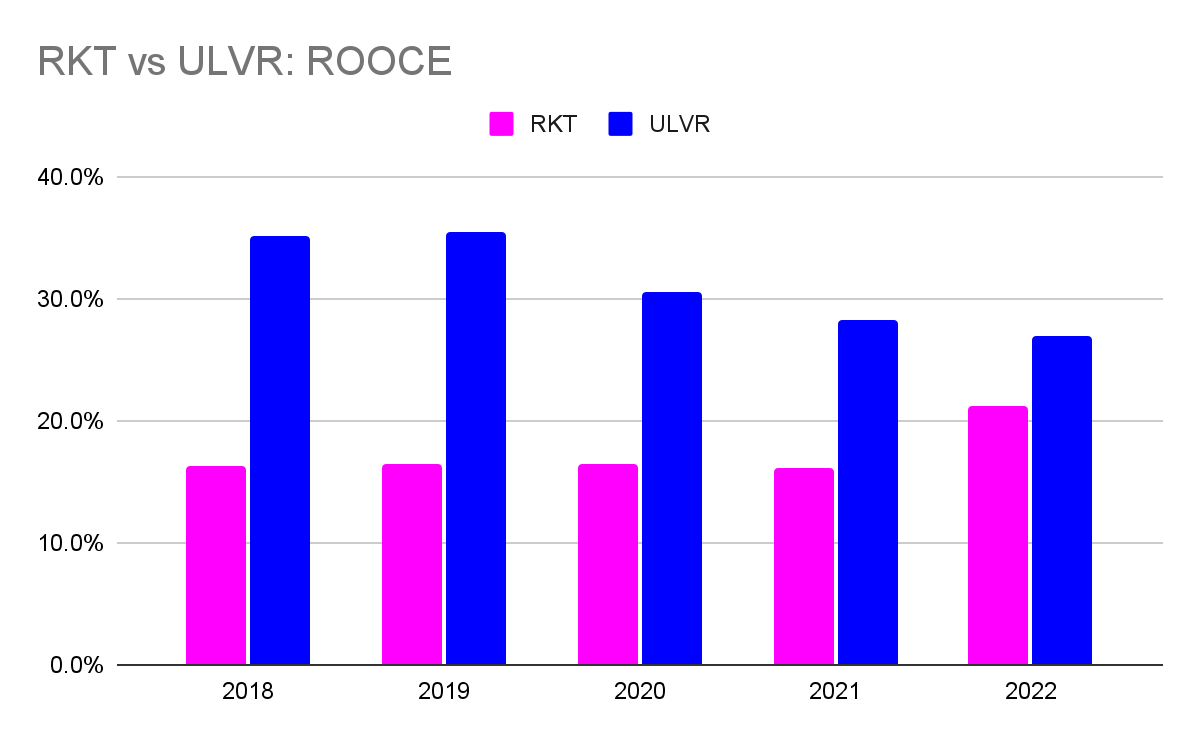

A way to get round this is to calculate ROCE by excluding goodwill from the capital employed. This gives us the return on operating capital or ROOCE.

Source: Annual Reports

Goodwill accounts for a quarter of Reckitt’s total capital employed and more than a third of Unilever’s as both have made plenty of acquisitions in the past.

If we ignore goodwill, we can see that both businesses have very profitable operating assets earning higher returns than given by the ROCE number.

This insight is important as it gives the investor an understanding of the kind of profits that could be made from further investment in the business.

Investing more money into a business with a high ROOCE will drive higher future profits growth and this could be underestimated if you just rely on an ROCE calculation which includes goodwill.

A high ROOCE number is often a sign of a very good business. If this is accompanied by a very modest or disappointing ROCE number it is a sign that the company has possibly paid too much to buy some or all of the assets.

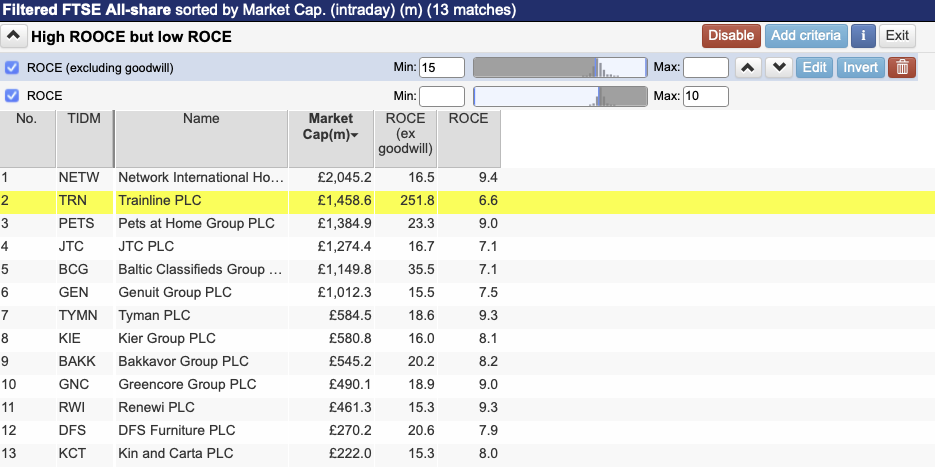

Here is a list of companies in the FTSE All Share index where ROOCE is a very respectable 15 per cent or more but ROCE is less than 10 per cent which would not be considered attractive in most cases.

Paying too much goodwill – especially when funded with lots of debt – has led to many acquisitive companies coming a cropper in the past.

The problems caused by other intangible assets

As well as goodwill, companies also acquire other intangible assets such as brands, customer lists, technology and software.

This can create lots of issues with the calculation of adjusted profits used in calculating ROCE or ROOCE.

The main problem is that there is a difference between the accounting treatment depending on whether certain intangible assets are bought or developed internally by a company.

If they are bought, then the value goes on the balance sheet and then amortised through the income statement over its estimated useful life – just like depreciation on a piece of equipment.

Lots of companies ignore this amortisation cost when calculating their adjusted profits, but is this reasonable?

It depends

If the company spends money to maintain an acquired brand or customer lists then this is usually charged against revenues and reduces profits.

To then include acquired intangible amortisation on the same assets would be a case of “double counting” and should rightly be ignored and excluded when looking at adjusted profit figures.

Where it gets difficult is when there are assets that are acquired such as software or technology which will eventually be updated or replaced.

Here, the accounting treatment is to capitalise money spent on the balance sheet and amortise it over its life in the income statement. When this happens, there is a strong case for not adding back the acquired intangible amortisation as this is a real ongoing cost.

It is virtually impossible to decide what is the right approach without often spending lots of time going through individual assets and even then you might not have enough information.

However, if you add back the amortisation to profit and ignore the reduction in balance sheet value caused by it (and therefore capital employed) you are boosting ROCE which doesn’t feel right.

A fairer measure is to add back the amortisation to capital employed. This is the approach used by Judges Scientific (LSE:JDG) whose business model is based around acquisitions.

My fellow SharePad writer Richard Beddard and I had an interesting chat about intangibles when we met up recently. He has made a persuasive case for ignoring intangibles when calculating ROCE as accountants can’t measure them properly.

As well as being a good friend of mine and one of the most thoughtful investment writers out there, I am going to respectfully disagree with him here.

While measuring them is difficult, they do represent operating assets (unlike goodwill) that have had cash spent on them and therefore measuring the return from them is important.

As you can see, ROCE and its calculation have the potential to become quite complicated for very understandable and valuable reasons. However, it does beg the question as to whether we should be using a simpler method instead.

Introducing cash return on cash invested (CROCI)

One of the main issues with ROCE is that it is based on accounting measures rather than cash or something close to cash.

For example, depreciation of fixed assets such as plant and machinery and amortisation are non-cash measures which reduce profit and the value of capital employed over time.

Depreciation and amortisation are treated differently by different companies which can make comparisons difficult. So much so that it would be nice if we could ignore these completely.

The good news is that you can do this with something called cash return on cash invested or CROCI for short. This approach is used by some professional investors who are looking for a simpler and less distorted measure of company profitability.

EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) is used to represent the cash inflow from a company’s trading activities. It is not a perfect measure, but is arguably better than using operating cash flow where changes in working capital can lead to a lot of volatility in that figure.

Also, changes in trading working capital – stocks, trade debtors and trade creditors – are timing differences and in most years are not the same as changes in profit. Instead, changes in these items are captured in the capital employed number.

Cash capital invested is calculated by starting with capital employed and adding back the cumulative depreciation and amortisation on tangible and intangible assets.

For example, £1 million of cash originally spent on a piece of equipment may have been depreciated to £100,000.

Under ROCE, £100,000 is used to calculate capital employed. Under CROCI, the £900,000 of accumulated depreciation is added back to get back to the initial £1 million cash invested. The same approach is used with intangible assets and amortisation.

As EBITDA excludes depreciation and amortisation costs, CROCI is comparing gross cash flows using EBITDA with gross cash capital invested.

CROCI = EBITDA/Cash Capital invested

Calculating CROCI for Unilever

Below is the CROCI calculation for Unilever for 2022. At 15.5 per cent it is lower than the 17.2 per cent ROCE but this is still a sign of a business with good rates of profitability.

|

€m |

2022 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|

|

EBITDA(A) |

11616 |

|

|

Capital Employed |

57965 |

57378 |

|

Cumulative Amortisation |

5247 |

4882 |

|

Cumulative Depreciation |

12351 |

11709 |

|

Cash Capital Employed |

75563 |

73969 |

|

Average Cash Capital employed(B) |

74766 |

|

|

CROCI = A/B |

15.5% |

Source: Annual Reports

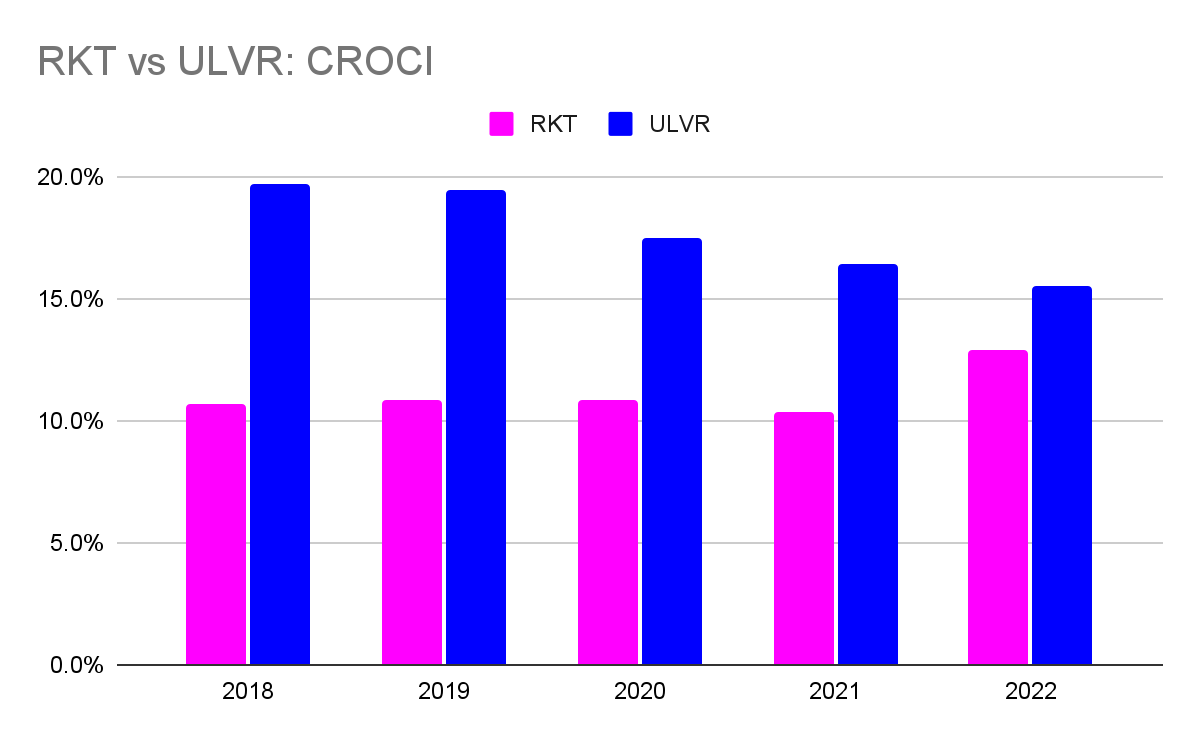

Again we can look at this ratio over time and compare it with Reckitt Benckiser.

One of the key advantages of CROCI is that it does not ignore the impairment of goodwill which arises when a company has paid too much for an acquisition.

When goodwill is reduced in value it disappears from the balance sheet, reduces the value of capital employed and boosts ROCE. By adding the reduction back, CROCI gives us a better measure of the returns on the cash spent.

As with ROOCE, you can look at operating cash capital employed by calculating CROOCI (cash return on operating cash invested. This is done by taking away the goodwill figure from cash capital employed.

Source: Annual Reports

What we can see with both Unilever and Reckitt Benckiser is that cash returns (CROCI) are lower than the accounting ones (ROCE) but are still at good levels.

There’s a lot to like about this approach in my view and I am hoping that it can become part of the toolkit in SharePad before too long.

~

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Phil? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.