In the first of a multi-part series on avoiding investment mistakes, Ben looks at how our own emotions and behaviour can lead to poor decisions, and what we can do about it.

When it comes to making good decisions, psychologists have found that investing is a field where humans are surprisingly bad at doing the right thing. Millions of years of evolution has wired our instincts to protect us from harm. But when you apply those emotions and behavioural traits to markets, it can end in a mess if you’re not paying attention.

This week marks the first article in a mini-series looking at some of the things you shouldn’t be doing as an investor, in order to get better results. It starts with a tour of our own psychology and how it plays against us.

In future articles, I’ll look at some of the external influences – including analyst forecasts, tips, news and internet bulletin boards – that can lead us astray. After that, I’ll explore some of the qualitative and quantitative features in shares that can break an investment from the start.

Why good investing starts with yourself

The past 18 months in the stock market have asked some tough questions of investors. After more than a decade of apparently stable monetary conditions, inflation roared back up the agenda. With it came a major change in priorities for central banks and a series of sharp interest rate hikes. Rather than growth, talk now is about the prospect of recession.

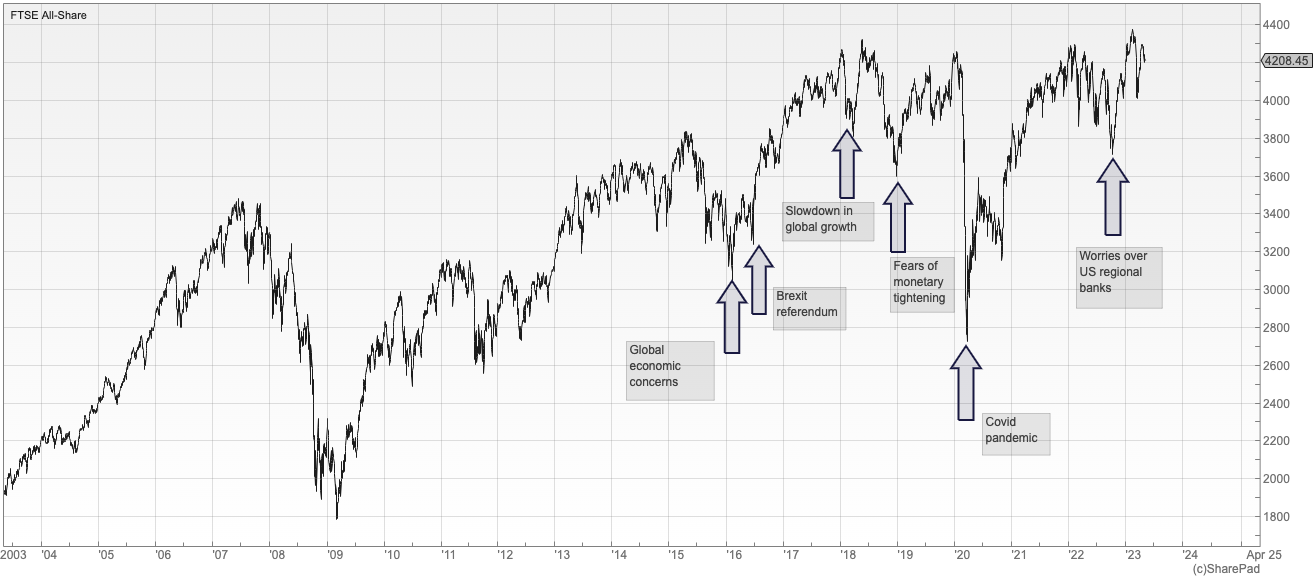

Even though the years since the financial crisis in 2008/09 have been dominated by central bank stimulus, it hasn’t all been plain sailing for shares. Investors have had to navigate a whole host of uncertain moments, some more serious than others.

SharePad: FTSE All Share 20-year chart

Look closely at the details of a long-term market chart like the one above, and you could pick out any number of times when equities sold off sharply. Often the reasons will be long forgotten, but you can be sure that emotions were running very high at the time.

Sudden sell-offs are not the only cause of psychological pain for investors, but they are an extreme example of moments when panic and volatility can lead us to poor choices. In order to avoid these missteps, what you need to do is know what they are, how they can manifest, and how to avoid them.

In the words of the Chinese military philosopher Sun Tzu, who wrote The Art of War: “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.”

Here are some of the most challenging psychological flaws that affect investors, and ideas on how to avoid them:

#1. Anchoring (over-emphasising certain information)

Anchoring is when decisions are made using too much emphasis on one (usually the first) piece of information. The anchor becomes a reference point from which all other decisions are made.

Anchoring is such a powerful force that it’s been credited as a driver of price momentum in markets. That is because it arguably causes post-earnings announcement drift, where prices creep higher as investors only slowly accept that an already high price deserves to move higher.

Solution: Anchoring is dangerous because it means having closely-held beliefs about a company or share, which can ultimately lead to falling in love with it. It’s preferable to keep an open mind and accept that the strengths and weaknesses of a share will inevitably change over time.

#2. Optimism and overconfidence (emotional trading is costly)

Psychologists have found that people tend to underestimate the chances of negative things happening to them and overestimate the chances of positive things happening. This inherent optimism can be dangerous because it implies that investors may think they have more control over events than they actually do (see Action Bias).

Optimism and overconfidence can lead to unnecessary and reactive (and expensive) trading, excessive risk-taking and chasing returns.

Solution: Avoid the risk of being influenced by emotion by having a long-term investing plan, checklists for decision-making and strict buying and selling rules. It is important to take your emotions out of the decision-making process.

#3. Action Bias (be patient)

Faced with uncertainty, humans instinctively want to take action in order to be seen to be controlling events and making an effort to influence a situation. This Action bias is at odds with the fact that ‘doing nothing’ is a core component of investing, which allows compounding to continue uninterrupted.

Market volatility is a classic trigger of Action bias, where ‘doing something’ may feel like the right thing to do, but can actually lead to worse outcomes. It is similar to another bias called Illusion of Control, which is the tendency for humans to think they have much greater control over events than they really do.

Solution: The answer to Action bias is to have a long-term strategy you can be confident in. Do the planning upfront so you can be prepared for times when markets sell off sharply.

#4. Disposition Effect (selling winners and holding losers)

The Disposition Effect describes the well-known investment error of holding ‘losing’ positions and selling ‘winners’. This is similar to another behavioural mistake called Loss Aversion because it instinctively tries to duck the misery of accepting a loss.

Humans feel the pain of loss much more than the gratification of a win, so selling winners is much easier (although often a big mistake) than crystallising the loss on a losing position.

Solution: Pre-planned buying and selling rules can help avoid the mistake of trading positions based on recent price performance. Bear in mind that the short-term uplift from selling winners could lead to Regret Aversion (see below), which could make things worse.

#5. Regret Aversion (fear of making the wrong choice)

When circumstances or luck have gone against you, the emotion you feel is disappointment. By contrast, when it’s your own decisions that have led to an unsatisfactory outcome, what you feel is regret.

Regret Aversion is a cognitive error that tries to avoid the misery of realising that you have made the wrong choice. This fear of the outcome can lead to indecision and inaction because of a fear of personally being responsible for making the wrong decision.

Solution: Regret aversion is arguably a major cause of procrastination, which can be costly if it means deferring a decision that might be in the best interest of your portfolio. Again, checklists and pre-prepared plans can help here, but ultimately it’s about remaining as emotionally detached as possible.

#6. Confirmation Bias (listening to those who agree with you)

This is thought by some to be the most dangerous of all the psychological flaws suffered by investors. Confirmation Bias is the tendency for people to look for and interpret information that supports what they already think or believe.

It can lead to ignoring counter-arguments and differing opinions and instead create a reliance on certain sources that confirm existing views. It could be reading the research of like-minded analysts, or trawling through bullish posts on internet discussion groups or even relying too much on what the company itself is saying.

Solution: Confirmation Bias can lead to a loss of objectivity so it is important to remain as open-minded as possible on an investment, seeking out broad views and listening to both the bull case and the bear case.

A plan for keeping calm in any market

Benjamin Graham, the grandfather of value investing, once said: “The investor’s chief problem – even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.” What he meant was that investing is a discipline where psychology plays a vital part in successful outcomes.

It is worth having plans and checklists to support you when it comes to making decisions in good times and bad. They might include:

- A document of your long-term strategy and goals

- A plan of action for both up-markets and down-markets

- A checklist that covers what to buy and sell, and when

- Play devil’s advocate with investment ideas

- Seek out contrary views and evidence that an investment case has changed

- Be objective and beware of the risk of taking impulsive decisions

- Unless it is part of your plan, keep trading to a minimum to keep costs down and let compounding do its job

Ben Hobson

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Ben? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for ‘share chat’.