Richard takes a first look at Dechra Pharmaceuticals, a company that has grown profit at a compound annual growth rate of 19% since 2013, yet its share price has halved this year.

The financial year ending in June 2022, was Dechra Pharmaceuticals’ 25th anniversary. It was also the year the company joined the FTSE-100 index, establishing it as one of the stock market’s top 100 companies by market capitalisation.

Dechra is a very different business to the one that incorporated in 1997. The company came into being when it was spun out of Lloyds Chemist (now Lloyds Pharmacy). Then it was National Veterinary Services (NVS), a distributor of veterinary products, and a couple of small product manufacturers.

Many of the medicines NVS distributed were meant for humans because specific pet medicines had not been developed to meet the growing expectations of the public for pet treatments and the growing capabilities of vets.

The GARP setup

In 1998, Dechra’s company adjusted profit was just £5 million, compared to £174.3 million in 2022. This increase in profit reflects two things: the company’s metamorphosis into a developer, acquirer, and manufacturer of pharmaceuticals, and the growth of that business

This metamorphosis started soon after Dechra floated in 2000, when it recognised the opportunity to invest the cash it earned from distributing other firms’ pharmaceuticals and pet accessories to develop its own medicines, principally for cats and dogs.

As a distributor, it was in a good position to work out which products would be profitable and popular, and it set about developing new products, acquiring them from other veterinary pharmaceutical companies, or acquiring whole businesses.

Buying businesses also expanded Dechra geographically throughout Europe and the USA until, by 2013, it was earning more from pharmaceuticals than it was from NVS and laboratory services, another strand of the business it had grown by acquisition.

That year, Dechra decided to double down on pharmaceuticals by selling the “Services” division, which gave it the financial firepower to increase product development, and the acquisition of medicines and pharmaceutical businesses.

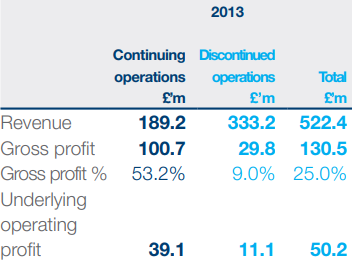

The annual report from 2013 shows why. Developing and manufacturing pharmaceuticals was a much more profitable business than distribution and laboratory services:

Source: Dechra Pharmaceuticals annual report 2013

In 2013, Dechra earned £39.1 million or 78% of total profit from continuing operations (pharmaceuticals), from just £189.2m or 36% of total revenue (turnover).

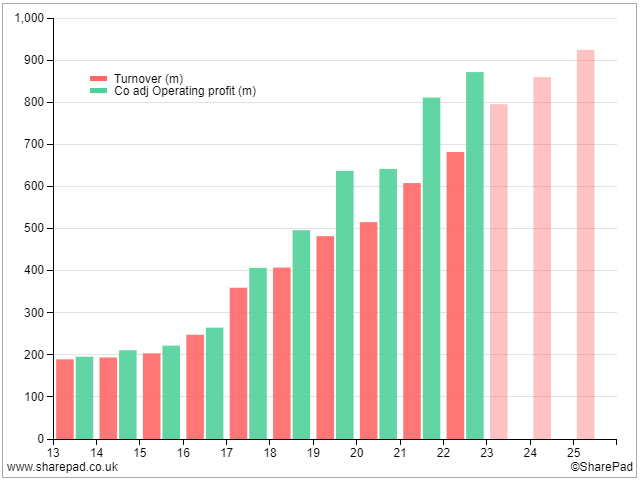

The record in SharePad shows that turnover and profit declined in 2013, because the company sacrificed 64% of its turnover and 22% of its profit when it sold the Services division.

In the nine years since 2013 though, the pharmaceuticals business has grown turnover to £682 million at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15%. Company adjusted profit has grown at a CAGR of 18%.

Sustained and rapid growth had already caught the eyes of investors willing to pay high multiples of profit for Dechra shares in the expectation of more growth.

Hence the company was propelled into the FTSE 100 by its ever-rising share price.

Monday 20 December 2021, the day Dechra ascended to the FTSE-100 index is, ironically, pretty much the company’s stockmarket apogee to date. It had, since flotation in 2000, risen by more than 4,000%. Since December 2021, the share price has halved, which means today it has risen a mere 2,000% since flotation.

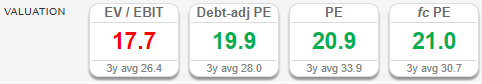

Pricey growth stocks have gone out of fashion this year, and that means that while Dechra shares do not look obviously cheap, judging by simple valuation metrics they do not look outrageously expensive:

Source: SharePad

That is the setup. We are looking at a business that has grown rapidly and profitably in an undeveloped market, and the shares may be available to us now at a reasonable price. It is what the GARP acronym (Growth At a Reasonable Price) was invented for.

If Dechra can sustain growth as SharePad’s forecast turnover suggests, the upward trend should reassert itself.

There are reasons to believe it should.

It is reassuring when the current managers of a business have also been responsible for its past success. Dechra has had the same chief executive throughout its rise. Ian Page was promoted to the role in 2001 from within NVS, and he had previously worked through the ranks of a rival distributor to become its boss.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and other companies have followed Dechra’s path. One is Animalcare, also listed in London, a distributor that developed its own pipeline of pharmaceuticals and then merged with another European distributor.

While Dechra’s position in the FTSE-100 must be in jeopardy, SharePad currently ranks it the 137th biggest company by market capitalisation listed in London, perhaps I have stumbled upon it at an opportune time.

Half a glass

Dechra has not grown entirely under its own steam though. It has issued more shares to fund acquisitions and relies on outside finance in the form of borrowings and leases to fund its operations and acquisitions.

SharePad tells us that in 2013 Dechra had 87.2 million shares in issue compared to 109 million today, an increase of 25%, which is another way of saying that shareholders who have not added to their holdings since 2013 own proportionately less of the business and have a proportionately lower claim on its profits.

The share count has increased at a CAGR of 2.5%, which offsets some of the growth in profit, but not much.

Assessing the company’s dependence on outside finance is tricky because of accounting rule changes that have brought leases onto company balance sheets.

To compare current levels of borrowing including leases with the past we must approximate the impact of the regulations (IFRS 16) on earlier results.

Dechra’s tangible assets were 70% funded by debt and leases in 2022, which is considerable but it has been more and less dependent on outside finance during the past nine years according to my calculations.

When we look at the annual report in 2023, I imagine Dechra’s obligations will have increased considerably and SharePad’s forecasts agree. That is because after the financial year ended in June, the company made two big acquisitions.

It bought Piedmont Animal Health for £175 million and Med Pharmex for £221.5 million. The combined total investment of nearly £400 million is equivalent to well over two years of adjusted profit (and a considerably higher multiple of free cash flow), although not all of that spending will find its way onto the company’s balance sheet.

Dechra raised £184 million from investors in a placing in July to fund the acquisition of Piedmont, which diluted shareholders who did not stump up more cash by a further 5%.

Two other numbers may be cause for concern. One is cash conversion, which has been low in recent years due to elevated levels of capital expenditure. Mostly this relates to intangible assets, principally medicines bought from other pharmaceutical companies.

The other is Return on Total Invested Capital, which compares profit to the investment required to generate it including the unamortized cost of acquired businesses. This is probably the strictest profitability ratio and Dechra achieved a 9% after tax return in 2022. To my mind this modest return on its investment implies the company has paid a fullish price for acquisitions.

It looks to me that Dechra is straining every sinew to grow. How we respond to that as investors depends on whether we are glass half-full or glass half-empty kind of people.

If Dechra has invested well, growth will follow, but there is not much margin of safety.

These are my first impressions. Having scratched the surface of the business and its strategy I have ignored three relatively small divisions. Pet medicines is by far Dechra’s biggest and apparently most promising market (probably because people are so attached to their pets, they are prepared to pay a lot to keep them well).

The company also supplies medicines for horses and therapeutic pet foods, both profitable niche markets but perhaps limited in their growth potential. And it supplies antibiotics to large poultry and pig farmers.

This high volume low margin business is very different from the rest of Dechra and I wonder why it persists with it. Farmers are under pressure to reduce the use of antibiotics because it encourages antibiotic resistance in animals and humans.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard