Prompted by a SharePad user, Richard scares himself silly when he examines how sensitive the pension fund of one of his shareholdings is to changes in the rate of inflation.

Other people notice things that we do not, which is one of the many reasons I value the emails from people who read my articles.

Tony, a SharePad user who read my last article on RM, followed up with some observations about the effect of inflation on defined benefit pension schemes still used by some companies (including RM), and an invitation for me to comment.

Tony’s interest in investing started in the 1970s, so he probably has an unusually informed perspective on inflation.

Most private sector investment schemes are defined contribution schemes. Typically a company pays into these schemes along with employees but that is where their obligation stops.

The pension scheme contributions are a cost, like paying salaries, and we do not have to be especially concerned about them.

If the pension does not deliver an adequate income in retirement, it is the retired employee’s problem, not the company’s.

Defined benefit schemes were the standard decades ago, at least for the private sector (they are still widespread in the public sector).

Although most companies have stopped paying into these schemes, some are still on the hook for obligations built up before they closed them.

As the name implies, defined benefit schemes promise a specific income. It is related to pensioners’ salaries when they were employed.

This means the obligation is of an unknowable size. It depends on factors that can only be estimated.

The factors include how old the employees will be when they retire, how much their pay will increase before they retire, how long pensioners drawing on the scheme will live, the rate of inflation (because pension payments are usually indexed to it in some way), and corporate bond yields.

Corporate bond yields (the interest rate on corporate bonds) are used to discount the future value of the pension obligation back to its present-day value so we can see how much funding is required today.

Actuaries calculate the value of the obligation and the scheme’s assets (some of which will be estimates too), and the difference between the two, which will be a surplus if the assets are worth more than the obligation and a deficit if the obligation is worth more than the assets.

Because the assumptions used to calculate the obligation change from year to year, and so to does the value of the assets, the difference between the two can change dramatically,

If it is a deficit, it is a debt and it appears as a liability on the company’s balance sheet. But it is an odd kind of debt, because of its shape-shifting behaviour.

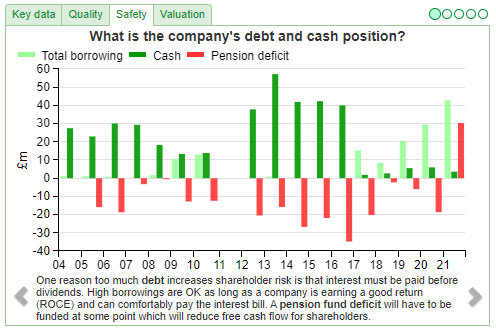

Tony shared this natty chart of RMs borrowings and pension deficit, which you can see in the Summary tab of the Financial section of SharePad to show how variable the deficit can be.

Source: SharePad

As you can see from the red bars, for a long time RM had a deficit, but in 2021 it turned into a £30 million surplus. That sounds like a good thing, but if it can go one way, it can also go another.

In its annual report, RM explains that the surplus was achieved by, “…better than expected returns on scheme assets, together with an increase in the discount rate, which is based on corporate bond yields, both of which were partially offset by an increase in inflation.”

The upsetting thing about movements in pension deficits is they have absolutely nothing to do with a company’s performance as a business.

When you buy shares in a company with a large defined benefit pension scheme you also own a share in its obligation to pensioners, which can land you with an unwelcome liability almost out of nowhere.

And it will impact the performance of the business and returns to investors because money channelled into the pension fund is money that cannot be used to pay back debt, fund strategic investments, pay dividends, or just keep the company afloat if it is in trouble.

Tony is particularly worried about the impact of inflation. He says: “My gut feel is that the presence of any defined benefit scheme makes a company uninvestable unless it is very tiny and legacy only.”

Avoiding companies with big obligations

Hitherto, I have been a bit more relaxed about companies with defined benefit pension schemes. Often they are well-established firms, the kind of business I like, and they have lived with their pension obligations for a long time.

Basically, though, I agree with Tony. A large defined benefit pension scheme is high risk. What remains is to determine what is large and what is legacy. The second question is easier to answer than the first.

The annual report tells us whether a company’s pension scheme is closed to new members (in my experience almost all are) and whether it is closed to new payments by existing members (also often true).

The second question is a matter of judgement.

Most people look at the deficit, which is easily found on the balance sheet and as a data point in SharePad’s data trove, and compare it to the size of the company or its profit or free cashflow.

Popular rules of thumb include avoiding companies that have deficits greater than 10% of their market capitalisations, or companies that could not pay off their deficits from one year of profit or free cashflow.

Because the deficit is so volatile, these measures are not very useful to long-term investors.

I prefer to use the size of the company’s pension obligation, as calculated by the actuaries.

To find this, we need to look into the notes to the accounts (there is an example in the final section of this article).

My rule of thumb is to question any potential investment where the company’s pension obligation is greater than its turnover or the capital required to run the business.

To my mind, if the pension scheme is bigger than the business, then management is likely to be spending lots of time and effort thinking about it, and perhaps I should be too.

Until Tony emailed me, I was happy with this rule of thumb. It allows me to invest in well-established businesses, without worrying too much about their pension schemes.

Rules of thumb are liberating, but they can also make us complacent…

How to spook yourself

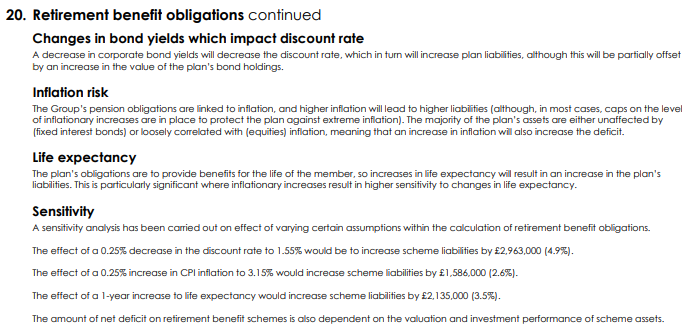

If you really want to spook yourself take a look in the notes to the accounts of a company with significant defined benefit pension obligation and you will find a sensitivity analysis:

Source: Churchill China annual report 2021, note 20

The sensitivities themselves are estimates, and show how susceptible the variables used to calculate the pension liability are to change.

Taking inflation in isolation, Churchill China’s pension obligation would increase by 2.6% if inflation rises 0.25%.

Of course, inflation has increased much more than that. Imagine if it increases by 10%, less than some predictions. Other things being equal, that would be enough to more than double Churchill China’s obligation were it not for safeguards I will talk about in a minute.

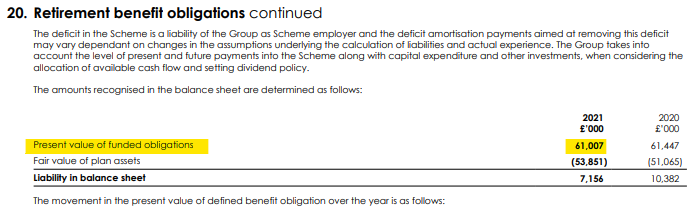

Churchill China’s pension obligation is revealed earlier in the same note:

Source: Churchill China annual report 2021, note 20

The obligation is £61 million, the same as the company’s revenue in 2021. That year, though, the business only required about £38 million in operating capital so Churchill China already breaches my rule of thumb and, it looks like it has the potential for that breach to widen considerably.

It may not though, for two reasons.

First, like many pension funds, Churchill China’s inflation-linked pension obligations are capped, which protects it from “extreme” inflation. The level of the cap is undisclosed but the company tells me it is 5% and Google searches tell me that 5% is typical of many companies.

Secondly, inflation will not move in isolation, and as we bring other variables into play things get much more complicated.

For example, corporate bond yields have risen, which increases the discount rate and reduces the present value of the pension obligation.

Because of this and movements in other variables, Churchill China tells me it believes its pension deficit might have shrunk when it remeasures it at the end of the year, should current economic conditions persist.

It is interesting that at both RM and Churchill China the sensitivity of the funds to rising bond yields apparently more than mops up the sensitivity to inflation.

But Tony has reminded me of the essential unfathomability of defined benefit pension schemes and encouraged me to check that the companies I have invested in with them have inflation caps.

I may apply my rule of thumb more assiduously too.

Thanks Tony!

PS

To brush up on my knowledge of pension funds, I turned to Phil Oakley’s book “How to Invest in Quality Shares.” It has a whole chapter on pension funds entitled “The Dangers of Pension Fund Deficits”, which is in a section entitled “How to Avoid Dangerous Companies”.

I think we know where he stands.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.