30-bagger Goodwin has pivoted towards higher-margin contracts to widen its competitive ‘moat’. Maynard Paton weighs up the engineer’s haphazard financials with the delightfully old-school management.

This quote from Richard Beddard caught my eye the other week:

“If something truly special is incubating, we may profit from our investment for decades.”

I am always up for profiting from an investment for decades.

Richard was writing about “pivots” — companies that are adapting to change by “incubating another better business“.

He highlighted four examples and today one of the quartet — Goodwin, a £277 million market-cap engineer — goes under my SharePad microscope.

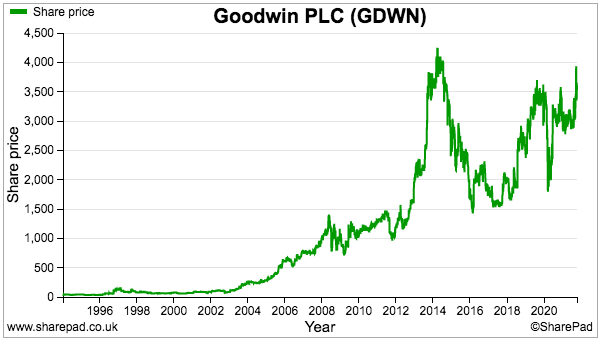

Richard described these pivots as “decent but humdrum” businesses, but do not let that put you off. Goodwin has 30-bagged during the last 20 years and a heritage of family management could indeed lead to decades of further profit.

Let’s take a closer look.

The history of Goodwin

R. Goodwin & Sons was established during 1883 as an iron foundry next to the Caldon canal near Stoke-on-Trent.

The business supplied castings to local steel and pottery businesses and today still manufactures castings, still operates from the same site and is still run by the Goodwin family:

The castings Goodwin presently manufactures have moved on from those of 1883. Orders today often involve bespoke product designs for enormous overseas projects. Customers are attracted by the group’s high-integrity manufacturing, wide range of capability, competitive pricing and prompt delivery.

Goodwin floated during 1958 and for years struggled to report a meaningful profit. But a step-change occurred during the 1990s after John and Richard Goodwin took charge. The brothers redirected efforts away from manufacturing products under license and towards developing in-house innovations.

These days Goodwin is probably best known for its check valves used in pipelines within the oil and gas industry. Other group products include radar antenna systems, slurry pumps, jewellery casting powders and a heat-resistant mineral called vermiculite.

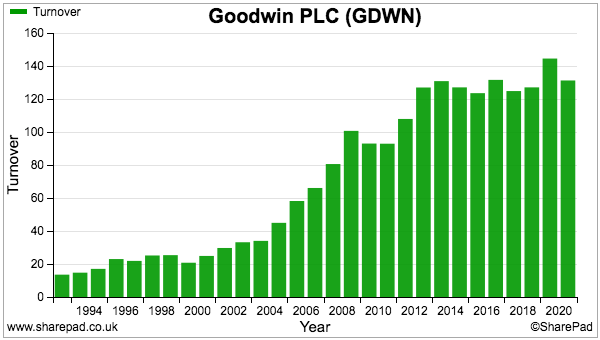

Revenue and profit soared during the early 2000s…

…and old annual reports explain how progress was buoyed by greater demand from oil and gas customers:

“The results were accomplished by the Group’s continued high level of sales into the oil and gas markets as well as the power generation markets worldwide.”

After treading water during the banking crash, Goodwin then enjoyed a further oil and gas boost from 2012:

“This further improvement in gross profit and pre-tax profit earned stems from the energy market sector having remained buoyant throughout the financial year, allowing us to make use of our investment on capital equipment working 24 hours a day, 6.5 days a week“

But weaker times were signalled during 2014:

“However, since the commencement of the new financial year there has been a noticeable slow down in order input from the oil and gas industries“

The slowdown prompted Goodwin to pivot towards other income sources.

Pivot and moat

Goodwin first revealed its pivot from oil and gas within its 2018 annual report. The commentary referred to military boat building and components for the nuclear industry:

“We have taken the opportunity over the past eighteen months to reposition the foundry such that we can address more efficiently very large high integrity castings for nuclear fuel reprocessing and for military boat building programmes in the USA, the UK and other overseas countries.”

Other commentary offers clues to Goodwin’s competitive moat following the pivot.

For example, not every foundry will wish to undertake a protracted approval process for the US military…

“We expect this contract to be the first of many going forward for the specialised steel that is required and that Goodwin over a four-year period obtained US Navy approval to manufacture last financial year.”

…nor will every foundry want to upgrade their facilities to manufacture 35-tonne castings:

“Goodwin Steel Castings has undergone major change… completing its extensive upgrade programme that gives it increased weight capability (casting up to 35 tonnes net weight castings in impact-resistant carbon, stainless and duplex stainless steels) and puts it in a unique global position.”

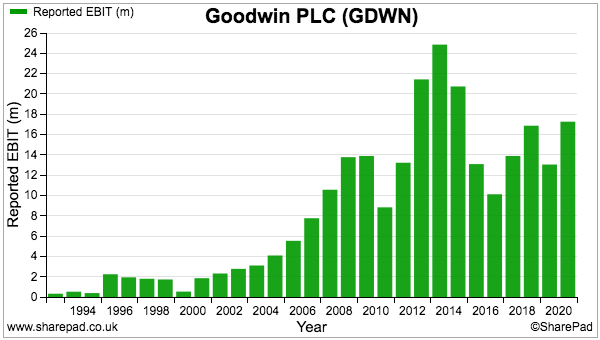

The pivot seems to be working, not least because the latest results revealed a remarkable divisional performance of sales falling 14% but profit soaring 34%:

“Whilst the Mechanical Engineering division’s revenue decreased by 14%, its pre-tax operating profit improved by 34% as a result of the higher margin contracts for nuclear decommissioning and naval vessel building programmes starting to ramp up as compared to the margins available in the declining oil industry.“

Reassuring, too, is an extremely long-term work horizon:

“The foundry is also having good success winning work for naval vessels both in the UK and the USA, all for long running programmes that will span decades to come in an area where there are significant time barriers to entry for other foundries.”

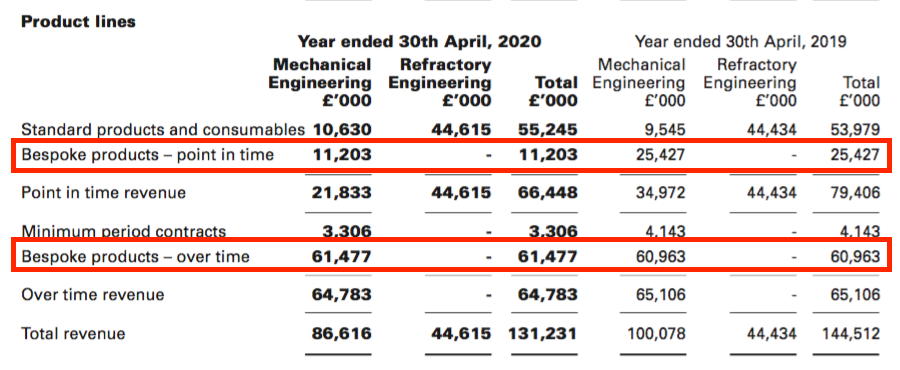

A downside to Goodwin’s new activities is an ongoing dependence on manufacturing bespoke products:

Orders for one-off castings will fluctuate more than demand for standard products, which could lead to profit remaining somewhat unpredictable…

Financials

The diminished oil and gas work alongside the pivot to find replacement income has created a haphazard financial record.

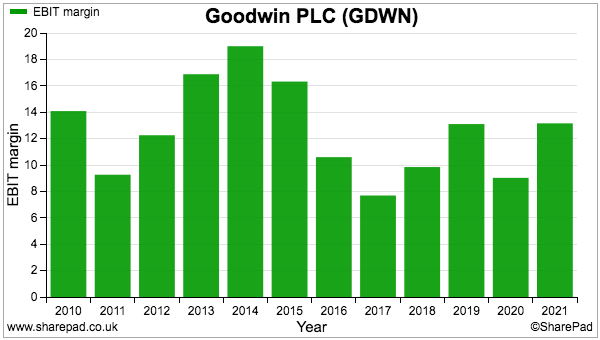

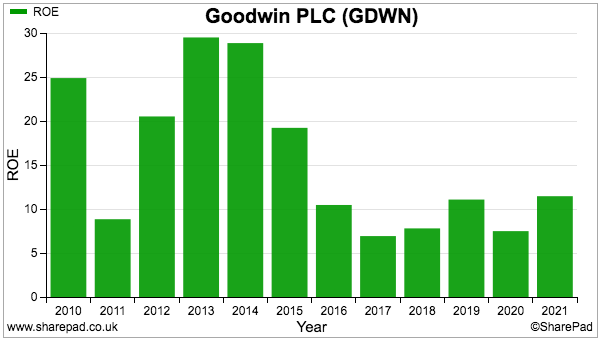

Operating margins and returns on equity have been up and down and have often flirted with modest single-digit percentages:

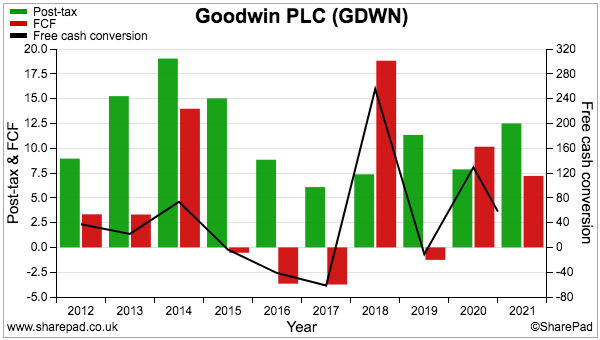

Free cash conversion (black line, right axis) has been similarly unpredictable:

Goodwin’s cash conversion has been influenced by:

- Additional working-capital requirements, and;

- Expenditure on tangible and intangible assets substantially exceeding the associated depreciation and amortisation charged against profit.

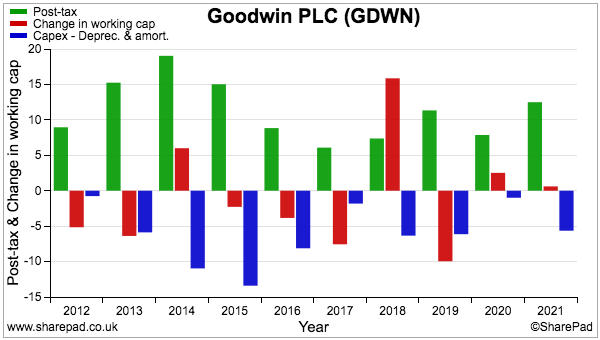

The following chart compares Goodwin’s earnings (green bars) to the additional working capital (red bars) and the ‘excess’ capital expenditure (blue bars):

The significant working-capital swings are perhaps not surprising given demand for Goodwin’s bespoke manufacturing can fluctuate from year to year.

Mind you, the net working-capital investment over the last ten years is £11 million, which does not seem that awful when aggregate operating profit during the same time was £161 million.

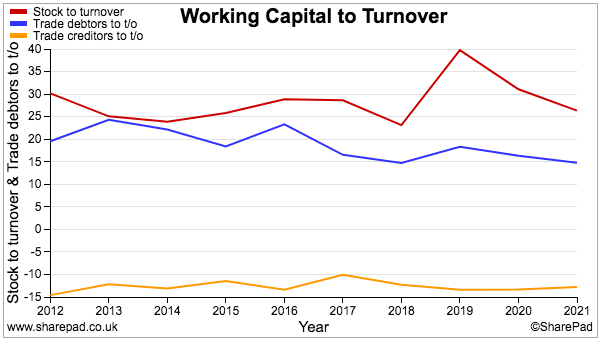

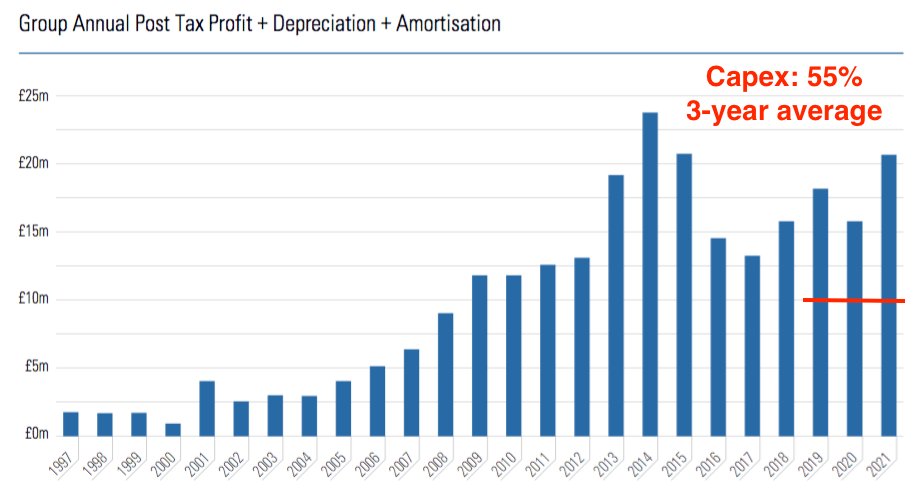

I am impressed by the chart below:

Despite the cash flow fluctuations, Goodwin has kept respectable control of stock, trade debtors and trade creditors.

Capital expenditure has meanwhile absorbed £112 million over the past ten years versus the £57 million expensed as depreciation and amortisation through the income statement.

The £55 million difference is significant and should be investigated. Perhaps earnings are flattered by hefty capex requirements with an inadequate accounting charge.

Capital expenditure and debt

The annual reports reveal where the majority of the capex money has been spent.

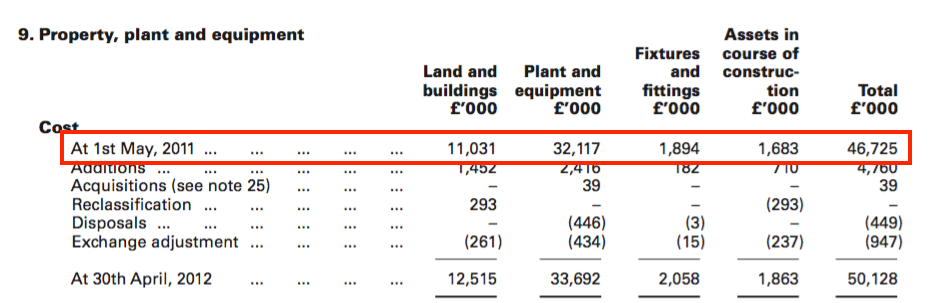

Ten years ago the historical cost of Goodwin’s then tangible assets was £47 million, of which £11 million related to land and buildings and £32 million related to plant and equipment:

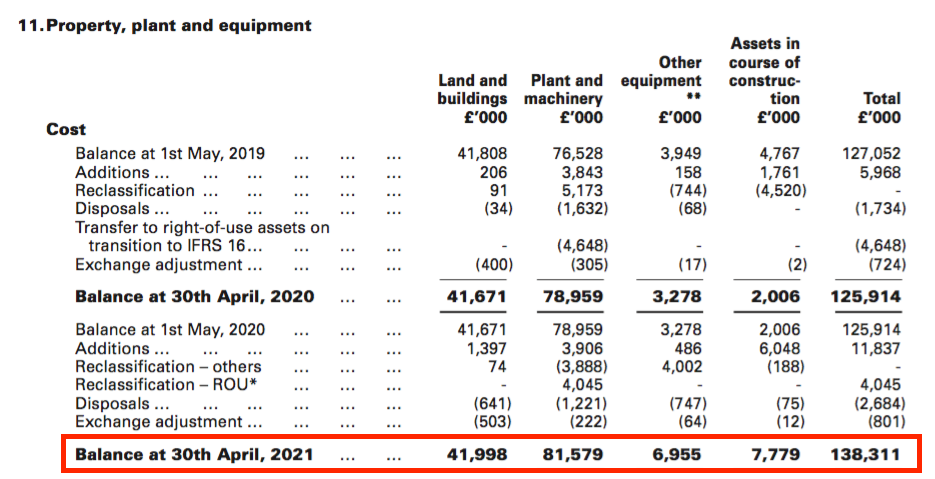

Today the historical cost of Goodwin’s tangible assets are £138 million, of which £42 million relates to land and buildings and £82 million relates to plant and equipment:

The figures tell us £31 million has been spent on land and buildings during the ten years. Land and buildings ought to hold their value over time and as such the associated depreciation ‘cost’ is generally academic to investors.

The figures also tell us £50 million has been spent on plant and equipment, much of which presumably went on the factory upgrade to handle those 35-tonne castings.

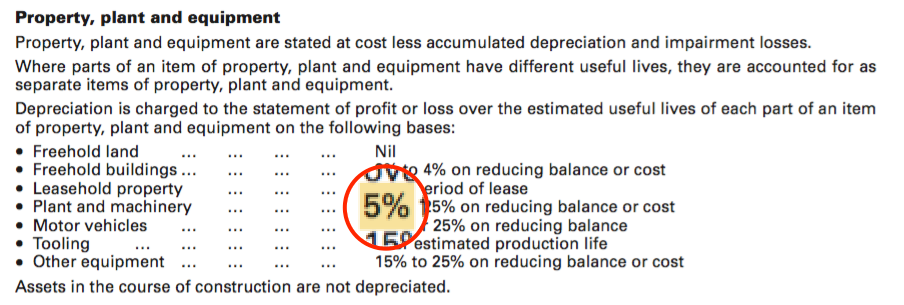

Exactly how long this new machinery will last before another upgrade (and perhaps another £50 million) is due is hard to say. Goodwin’s annual report shows a depreciation rate of between 5% and 25%…

…which implies some of the equipment could be still in use 20 years from now.

A lot can happen during the next 20 years, which could make the depreciation rate — and therefore Goodwin’s earnings calculation — somewhat optimistic.

Before 2016 the lowest depreciation rate for plant and machinery was 10%, which suggests Goodwin believes some of its equipment will now last twice as long as before.

Goodwin commendably addresses this capex issue by stating such expenditure will be limited to 55% of earnings plus depreciation plus amortisation on a three-year rolling basis:

By using this 55% limit, shareholders can adjust the depreciation charge for themselves to arrive at their own version of earnings.

Mind you, based on the last three years, the 55% limit represented £10 million a year but actual capital expenditure averaged £12 million a year.

All told, the 55% limit signals Goodwin is unlikely to be a ‘capex-light’ business, which has knock-on implications for its future cash conversion.

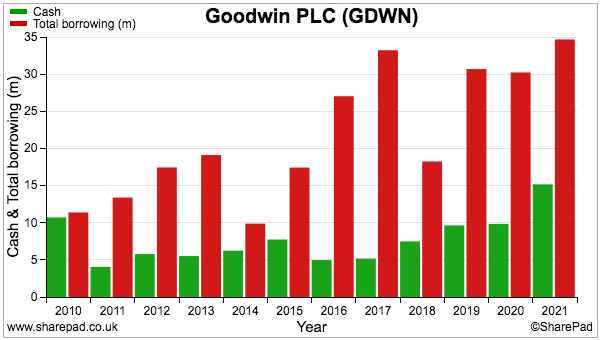

The capex requirements have left the business consistently operating with more debt than cash:

At least Goodwin has established a debt limit. Gearing (net debt to net assets) is presently 15% and ought not to exceed 30%.

Further reassurance comes from an interest-rate swap. The company has commendably fixed the cost of its borrowings to less than 1% until 2031.

Management and shareholdings

Corporate-governance box-tickers will hate Goodwin.

The board today is run by four sixth-generation Goodwins (Matthew, Simon, Timothy and Bernard) and the annual report notes nine different breaches of the Corporate Code. Contraventions include:

- The appointment of just one non-exec;

- The absence of a remuneration committee and a nominations committee;

- The appointment of former directors (the aforementioned John and Richard Goodwin) as audit committee members;

- The chairman being an executive, and;

- The low frequency of director AGM re-elections.

The non-compliance has of course not stopped the shares from 30-bagging.

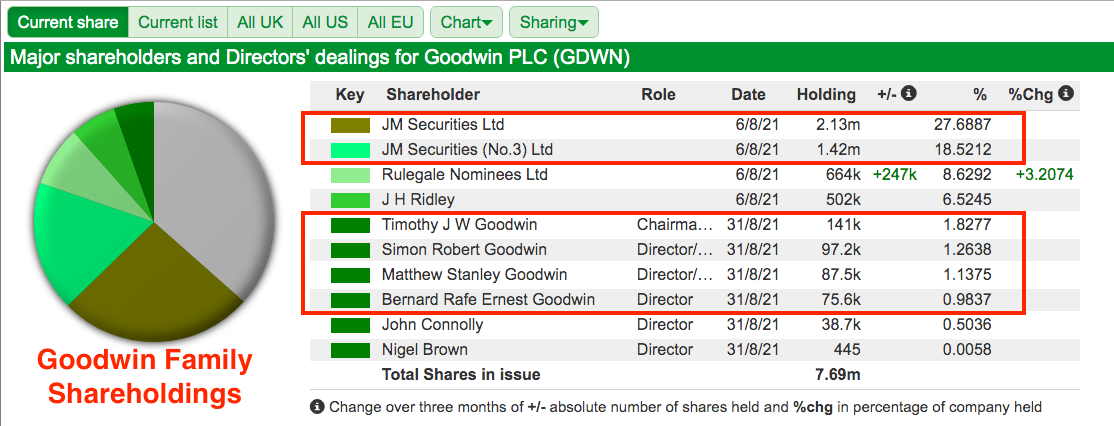

Trumping all of the corp-gov niceties is a genuine long-term shareholder alignment. The wider Goodwin family enjoy a 53%/£147 million shareholding, with the four execs owning 5%:

Other management positives include long tenures and the lack of succession worries. The sixth-generation execs have each worked at the firm for more than ten years and their ages range from 31 to 40.

The young Goodwins have kept the company delightfully ‘old school’:

- The annual report still contains only black and white text (and no pictures) and the front cover remains unchanged since at least the 1980s;

- The accounts still avoid declaring exceptional items, adjusted EBITDA or other such reporting irritants, and;

- The company still does not employ any financial PR nor commission any broker reports.

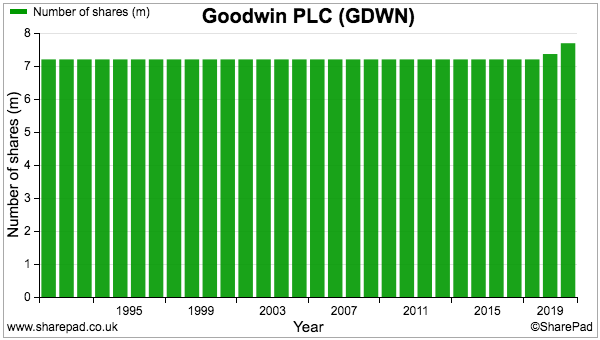

That said, the board did blot its old-school copybook by introducing the group’s first option scheme during 2016. The scheme increased the share count by 7%, which up until then had remained unchanged for at least 40 years:

Valuation and summary

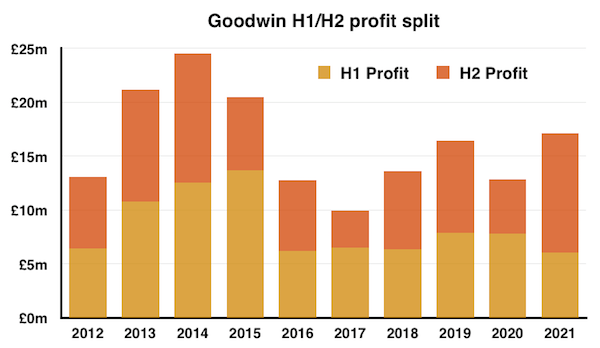

The aforementioned higher margins from the new nuclear and naval orders buoyed the latest annual results. Second-half profit for 2021 was in fact the highest in any six-month period since 2015:

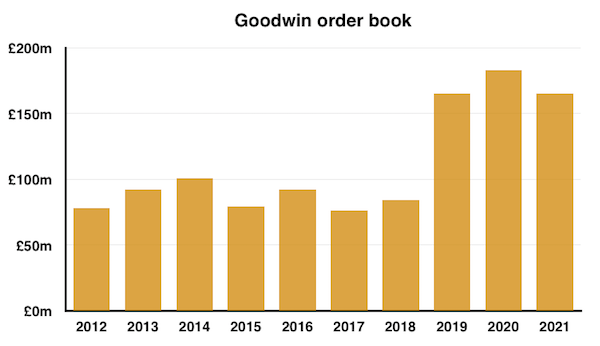

The new contracts have bolstered the group’s order book…

…and underpin management’s hopes of delivering “strong returns on the capital that has been invested to date“.

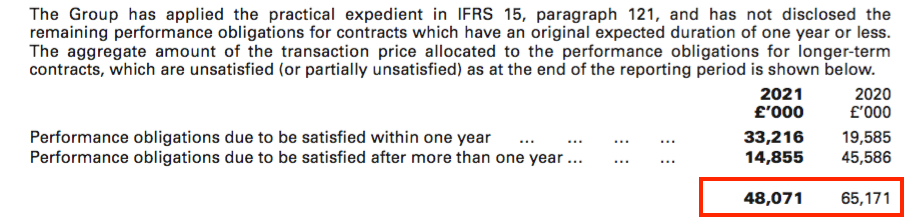

Note that the order book may not translate into steady annual income. The footnote below reveals the value of long-term work currently being undertaken — but yet to be recognised as revenue — dropped by £17 million last year:

Doubling up the bumper second half gives a possible operating profit of £22 million and perhaps earnings around the 230p per share mark.

The near-term P/E at £36 may therefore be 15-16x, which is not a deep-value bargain but entirely understandable given the substantial order book, higher-margin work, and the potential perhaps of a permanent pivot into a much better business.

Probably the dominant factor for predicting Goodwin’s future is management; the sixth-generation executives are extremely likely to remain in charge for the next 10-20 years.

And if the directors can ensure their family’s £147 million investment will ‘profit for decades’, the 30-bagger journey won’t end at the recent £36.

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Maynard writes about his portfolio at maynardpaton.com and hosts an investment discussion forum at quidisq.com. He does not own shares in Goodwin.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Great write up Maynard. Though a bit harsh on corporate governance issues.

When asked about : “The absence of a remuneration committee and a nominations committee” the Goodwin brothers smiled and said, whenever a company appoints a remuneration committee, the wages of management double over the next few years, and bonuses go into the stratosphere. Do you think that that would be a good use of shareholder funds?

This was before they started to pay management bonuses.

Any thoughts on energy costs for a business like this based in the uk?

Hi Roger

Thanks for the management scuttlebutt. I think only PIRC etc moan about the corp-gov issues. I did write the code breaches have not stopped the shares from 30-bagging!

I suspect GDWN will pay more for energy this year. The last annual report showed consumption equivalent to 70 million kWh.

Maynard

Hi Maynard,

I like the look of Goodwin as it has a lot of attractive features. Owner/managers, more than a century of building expertise, infrastructure, reputation etc. I also like the fact that it’s moving into designing and building harder to produce bespoke items rather than simply churning out widgets from someone else’s blueprint. That’s always going to be a more defendable business.

To be honest, Goodwin has always been a bit on the small side for me as I prefer FTSE 350 stocks if possible, but it’s valued at several hundred million now so it’s not exactly a tiddler anymore.

Could well be worth a closer look.

Thanks

John

Thanks John. Lot to be said for smaller companies with sensible owner managers that think longer term. Such leadership will share any financial pain with ordinary shareholders, which I like to think can limit the possibility of a major mishap. Manufacturing bespoke items is not ideal, but GDWN suggests it is one of the very few companies that can handle some of the orders.

Maynard