Animal breeder Genus Plc is at the forefront of animal genetics and highly valued by investors, yet standard measures of Return on Capital Employed (ROCE), a marker for quality, indicate only modest levels of profitability.

Unusually (for me) I rediscovered Genus because of an idea, rather than as a result of trawling through shares in SharePad.

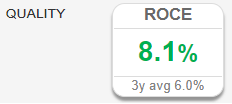

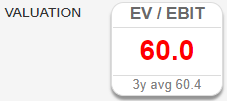

When I looked at the company’s financials in SharePad though, I almost threw it in the discard pile, because of the following two statistics.

|

|

As a seeker of good businesses at low prices, the basic metrics tell me Genus is the opposite. Return on Capital is a modest 8%, and the market value of the enterprise (Enterprise Value) is 60 times profit in 2021.

It looks like a humdrum business trading at a monstrously high share price.

The numbers, though, may be misleading us.

Finding Genus Plc

I rediscovered Genus after reading an article reporting that UK scientists have developed a new strain of wheat that makes less-cancerous toast.

The article said that by using gene editing rather than transferring genes between different species, the wheat might not be deemed to have been genetically modified.

Gene editing is more akin to selective breeding, a natural process, than genetic modification, and is therefore more likely to gain acceptance as a food.

Curiosity led me to filter SharePad’s news archive looking for companies reporting on gene editing.

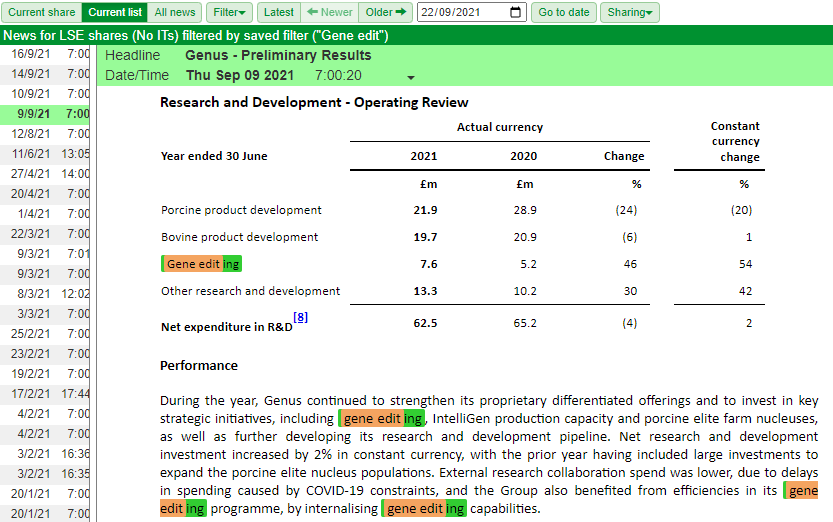

Perhaps unsurprisingly I found selective breeder Genus is dabbling in it. In fact it is more than dabbling. In its preliminary results published earlier this month, the company described gene editing as “a key strategic initiative”.

It says: “…gene editing and other breakthrough technologies may provide farmers with breeding animals that are fully resistant to some of the most devastating diseases globally.”

If Genus does not turn gene editing into an opportunity, other companies will probably turn it into a threat. Genus’ interest may be born of necessity.

In 2021 Genus spent £7.6 million, admittedly a relatively small part of its research and development budget, on gene-editing.

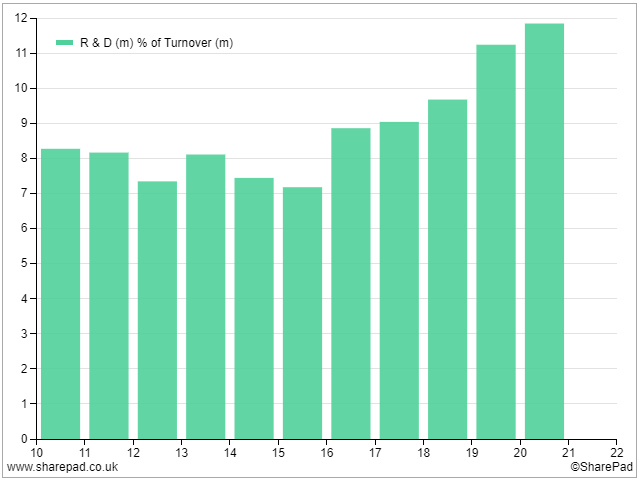

The company does not yet earn any revenue from gene-edited animals, but gene editing is part of a sizable and growing research and development programme.

Research and Development expenditure measured as a proportion of turnover has increased substantially from already high levels in recent years:

Something is afoot, but before we get excited about the potential for this new technology incubating within an established business, we need to address the profitability conundrum.

Profitability conundrum

Genus has a reputation as a world leader. Helpfully, the company’s 2020 annual report tells us it had a 16% market share in porcine genetics (pigs) compared to the second biggest competitor, which had a 7% market share. It is the second biggest bovine (cattle) genetics company with an 8% market share. The leader has an 11% share.

Genus’ strong position may well be an endorsement of the quality of the company’s pigs and cattle, which it sells to farmers so they can breed superior herds (it also sells semen). Scale may give the company a competitive advantage, which may in turn explain Genus’ high valuation.

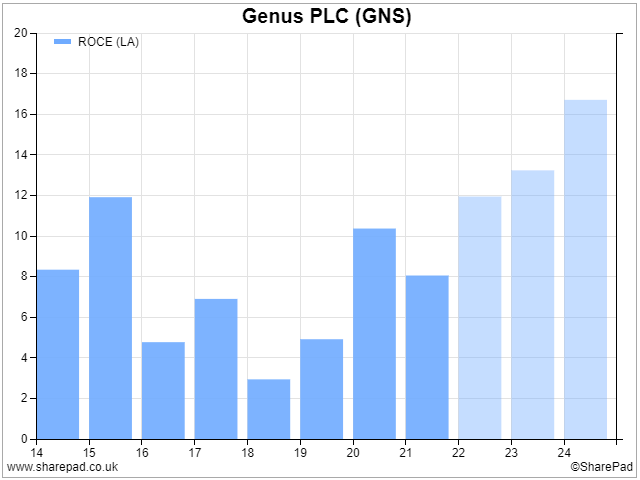

However, Genus’ reputation and market position does not result in particularly impressive ROCE (although, if the forecasts are to be believed, the future looks more rosy):

Source: SharePad > Financial charts

Genus thinks it is more profitable than the raw statistics show, and so do I.

At the end of its 2020 annual report, Genus includes an “Alternative Performance Measurements Glossary” in which it reconciles the standard measures of profit and capital with its own preferred measures.

It presents these measures after tax, although for simplicity’s sake I will stick with pre-tax measures like EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) used in the Return on Capital Employed calculation and EV/EBIT.

Adjusting profit

Genus primarily makes three adjustments to profit, it:

- Adds back the valuation movement in biological assets. Every year the company is required to recalculate the fair value of its herds by calculating how much cash it expects to earn from them in future and expressing it in today’s prices. Since the movement is treated as a gain or a loss it can have a big impact on profit, but it does not reflect sales and royalties during the year.

- Adds back the amortisation of acquired intangible assets. When a company acquires another company it must identify certain assets (in Genus’ case technology and customer relationships) that would not have been identified in the balance sheet had it created them itself. The resulting amortisation depresses profit and means the results of companies that have made acquisitions are not directly comparable with companies that have not.

- Adds back so-called exceptional items that it does not expect to recur in the normal run of business. Of the three, this is the profit adjustment I am least comfortable with. Unlike the previous two it increases the subjectivity of the accounts. Typically Genus adds back acquisition costs, which is fine – once a company is acquired it cannot be acquired again. It also adds back pension related losses (or deducts pension related gains), which are usually one-off adjustments. The other exceptional items that occur in Genus’ accounts are litigation costs, and restructuring costs, which may deserve a closer look.

If the adjusting item is positive, i.e. the company’s biological assets increased in value or it made an exceptional gain, we are adding back a negative cost and the adjusting item is deducted from profit.

Like many companies, Genus also adds back the cost of share-based payments to profit because they are not paid directly in cash. They are still a cost to shareholders though, and they are often a cash cost in a round-about way, because companies buy back shares to give them to executives. For this reason, I stubbornly include the cost of share-based payments in my calculations.

Adjusting capital employed

Genus makes two big adjustments to capital employed, it:

- Deducts the fair value of biological assets because this does not represent the cost of breeding its herds (it is a calculation based on the estimated future value expressed in today’s prices). Since we want to see how good the company is at allocating resources it makes more sense to use the historical cost as we do when valuing physical assets like plant and equipment. Historical cost tends to be much lower. In the full-year results for 2021, Genus reported the fair value of its herds was £337 million, but the historical cost was only £65.1 million. Having deducted the fair value of biological assets, Genus adds the value of the biological assets at their historical cost to its profit figure.

- Deducts goodwill. Goodwill is a historical cost, a fudge-factor representing the intangible assets accountants could not put a value on when Genus acquired other businesses. To remain in operation Genus does not need to create more goodwill, indeed it cannot be created as a result of normal operations. For the same reason I also deduct other acquired intangible assets in my calculations.

The adjusting information is easy to find in the full-year results for 2021 and the annual report for 2020 because the company tabulates its adjustments in the Glossary of Alternative Performance Measures.

For earlier years we must search more widely in each year’s accounts and the financial reviews that accompany them.

Before 2013, my trail ran dry. I could no longer find a value for the historical cost of biological assets so I could no longer adjust capital employed.

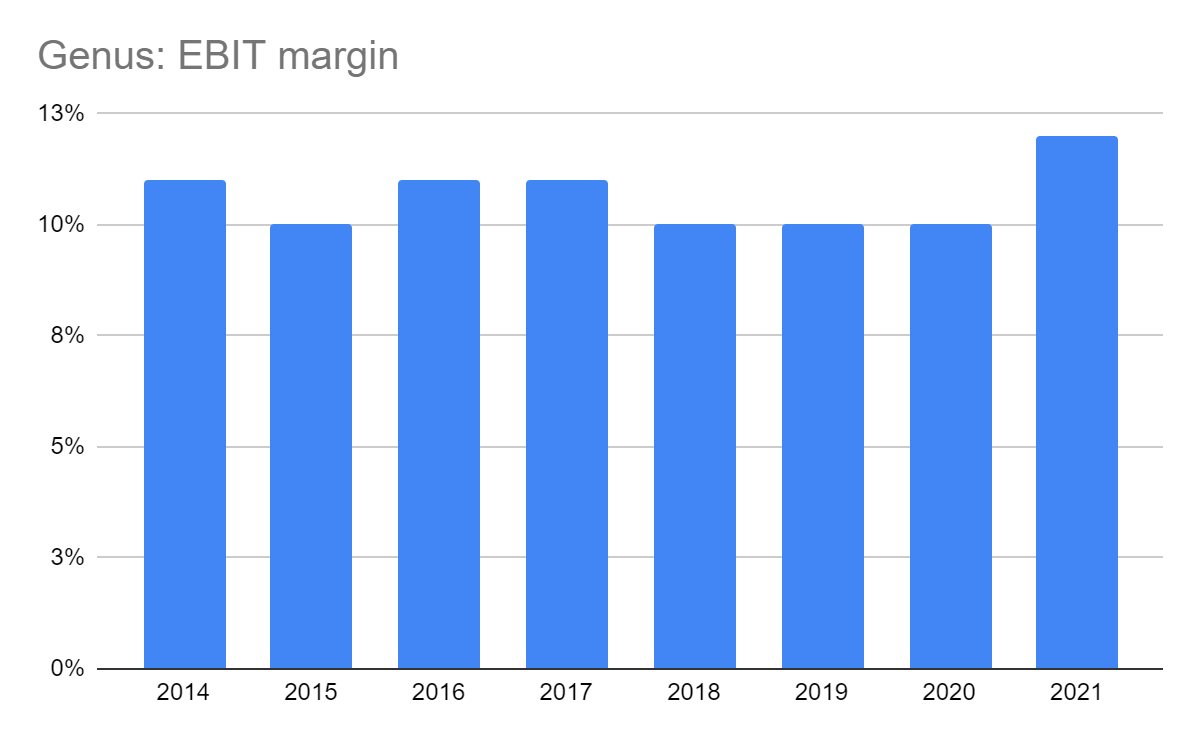

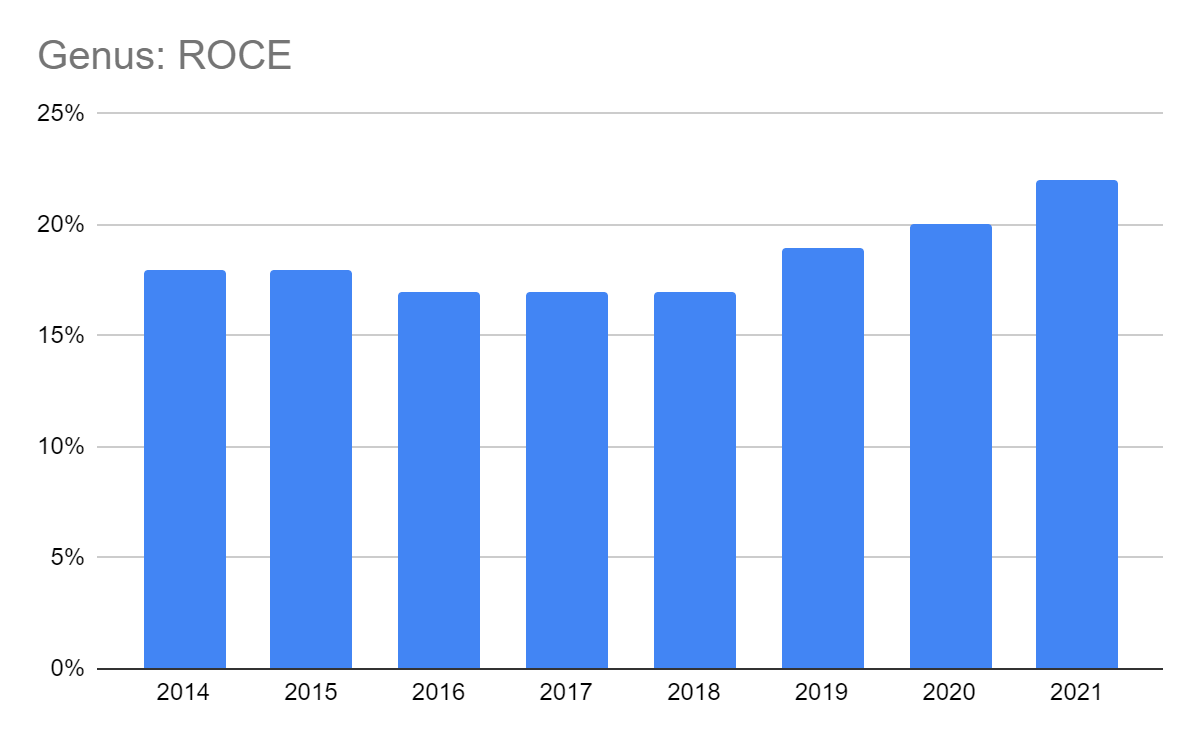

This is how I think Genus has performed over the last eight years:

Source: Author’s calculations from SharePad data and annual reports

These figures are a big improvement. Genus may well be a highly and constantly profitable business and feel I have taken a step closer to understanding the business and its prospects.

But days dwelling on Genus have shown me that it is a complicated business.

The company’s presentations are very thorough and give me some confidence it would be possible to gain an understanding of the science and its potential (the company seems to have numerous gene-editing patents, or have licensed them).

The future of meat

But worrying about the future of meat might leave me lying awake at night. In the UK we are eating less meat than we used to for health reasons, concern for animal welfare, and because meat production is a major contributor to climate change.

The change in taste is driving innovation in the food industry, where plant-based substitutes for meat are being developed. Although nowhere near commercialisation, cultivated meat products might also one day produce viable alternatives to farmed meat.

While these trends have yet to dent the growth in global meat consumption, which has been driven by increased prosperity in developing countries, there will perhaps come a time when they will.

If animals are no longer required to produce meat, or food that tastes as good as meat, animal genetics will be less relevant to the food industry.

There is one more hurdle between me and investment in Genus Plc. Adjustments may have restored some shine to profitability, but they do not make the shares look much cheaper.

I calculate an EV to adjusted EBIT ratio of 53.

Richard Beddard

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Interesting article