Richard examines Next’s bold strategy as it seeks to win the Internet by becoming an enabler of fashion brands. Surprisingly the strategies of the racier names in fashion retail look staid in comparison.

As a dedicated shareholder of Next, I have been following its strategic shifts with increasing anticipation.

The company has a habit of planting acorns and nurturing them into mighty oaks.

A partial history of UK fashion retail

Unlike the new generation of online fashion retailers led by ASOS (founded in 2000) and Boohoo (founded in 2006), Next’s history spans three centuries.

It started life as tailor J Hepworth & Son in 1864 and gave birth to NEXT, initially a chain of womenswear stores in 1982. Menswear stores, homeware stores, the mini-department stores that are typical today, and NEXT Directory, its mail order catalogue, followed in the 1980s as the company consolidated under the NEXT brand.

It beat ASOS to the punch, launching the next.co.uk online store in 1999 and in 2014 it started Label, initially a standalone site, now part of the mothership, that sells rival brands. Around the same time it began to develop its online presence in Europe.

I am not saying this was me, but in the 1980’s a teenager in search of, say, a leather bomber jacket might have biked to the nearest big town and ridden the escalators of C&A, Top Man, Debenhams, and Next until he found one with a nice furry collar.

Who is the retail king?

Most of these chains are closed now, but Next has moved with the times. You might not be aware, since the new online giants grab the headlines, but in many ways it rules the roost:

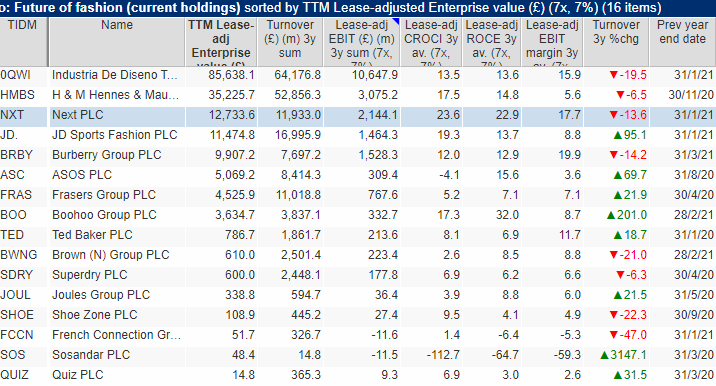

Source Sharepad: Custom table

Making comparisons is even more difficult than usual because the pandemic has dented the results of some companies (those with lots of stores) and boosted others (those without any).

In the Future of Fashion table above I have mitigated this somewhat by comparing cumulative turnover and profit (EBIT) over the last three years, and the averages of Cash Return on Capital Employed (CROCI), Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) and profit margin (EBIT margin), also over the last three years.

The table is sorted by Enterprise Value (EV), which is the market value of each company’s equity plus debt. The biggest two companies are not listed in London. They are there to remind us there are some really big competitors for our indiginous champions. The biggest is Inditex (Spanish), parent of Zara, and the second is H&M (Swedish). Both have substantial presences in UK high streets and malls, and online.

Inditex’s enterprise value is nearly seven times that of Next, which is the biggest UK listed fashion retailer.

In terms of turnover, Next is beaten into second place in the UK chart by JD Sports, although in terms of profit, Next reigns supreme.

When it comes to profitability, it depends what you measure. In cash terms, Next’s CROCI is unparalleled, better even than our continental overlords’, although its ROCE is second to pile-‘em-high, sell-‘em-cheap online retailer Boohoo. Britain’s fashion retailers may not be the biggest, but they are the most profitable.

Next’s profit margin is second only to luxury fashion brand, Burberry. We should expect high margins from a company selling £2,000 trench coats, but Next’s margins are delightful.

The only blot in the statistical case is Next’s negative turnover growth rate over the last three years. There is no hiding the fact that companies operating physical stores had a hard time during the pandemic, and that many physical retailers, Next included, were in decline before that. Up until the pandemic, though, Next had been managing this decline profitably.

Some physical retailers have grown according to the table, but this growth does not stand scrutiny. Joules’ and Frasers’ impressive-looking performances miss much of the pandemic because their most recent year-ends are more than a year ago. Frasers, by the way, is the mash-up of Sports Direct and House of Fraser. JD Sports’ growth is partly due to acquisitions (although it probably merits a closer look).

The online retailers led by Boohoo are clear winners in terms of growth but there is another perspective. NEXT Online has grown 42% over the last three years, admittedly slower than ASOS’ 70% and Boohoo’s 201%, but NEXT Online is almost certainly growing more profitably.

Comparing NEXT Online’s divisional profit margin with the group margins of ASOS and Boohoo favours Next as there will be central costs not included in the former, but the difference is considerable. NEXT Online’s average profit margin is nearly 20%, compared to less than 4% at ASOS and less than 9% at Boohoo.

In its own right, NEXT Online is a contender: slightly smaller in turnover terms than ASOS and still bigger than Boohoo, at least at the last count.

Investors, and shoppers, have been conditioned by Amazon to think that once the Internet retailers sail in, the hapless High Street dodos will be picked off one by one. But one of the dodos is evolving, perhaps even faster than the insurgents.

How to win the Internet

Doing justice to Next’s strategy is tricky in the third part of a three part article, because Next goes into great detail in its annual report and results presentation. Fitting it into Rumeld’s strategy framework of diagnosis/guiding principle/coherent actions should help.

The near infinite choice on the Internet and shoppers’ increasing propensity to embrace it is gradually by-passing Next’s competitive advantages: a large range of cunningly sourced products available from prime shopping locations. Next faces irrelevance.

Next initially decided that if it could not beat the internet-only fashion stores it would join them, putting NEXT Directory online, and then selling rival brands in its online store to increase its range and customer appeal.

But the guiding principle has evolved as Next has worked out how to gain advantage. Now it is “if you can’t beat them, enable them”, from which numerous coherent actions flow…

Though Next is a survivor from an earlier age of retailing, thanks to mail order and its adoption of the Internet, it has decades of expertise in warehousing, distribution, websites, and customer services as well as highly developed customer credit products used by many of its biggest spending customers.

Over the last five years it has redirected capital expenditure from its stores to its warehouses, making them more efficient so it can drive down the cost of online sales, not just for itself, but for its many partner brands.

This is one of the factors behind Next’s profitability, and also its partners’ because once it has earned its 15% margin, it reduces the commissions they pay (NEXT branded products earn higher margins).

Restraint and reinvestment is essential if Next is to be its partners’ most profitable sales channel, which is its objective, and if Next is to have a long-term future as an online fashion store.

But in 2019, Next revealed a much bigger ambition, to unpeel each layer of its platform and offer partners “Total Platform”, the whole infrastructure of an online business, the warehousing, distribution, websites, customer services and credit products it had developed over decades, so they can concentrate on what makes them special: product and brand.

Source: Childsplay Clothing, powered by Next

In the last year or so Next has taken on the online operations for three brands, Childsplay Clothing, Laura Ashley, and Victoria’s Secret, and it has two more in the works, a new and unnamed brand, and REISS. There are unlikely to be any more until next year at the earliest, because as well as making sure its software and systems are fit for these partners, it is developing them so they can be reused for the many partners that might follow.

Next believes its infrastructure will give these brands such a boost it is investing in some of them. It has a 51% stake in Victoria’s secret, a 33% stake in the unnamed new brand, and a 25% stake in REISS. Its share in their profits should, Next believes, earn it more money than the commission they will pay.

Acquiring brands outright, Next says, would crush their entrepreneurial zeal and reduce Next’s focus on its own brand. It wants to be an investor, not a manager.

Remarkably, Lord Wolfson, Next’s chief executive and the architect of Next’s strategy, denies he is an architect at all, or that there is a grand plan.

He says the company follows the money. As the customer has embraced the Internet, Next has learned and re-learned how to make good returns. Perhaps good strategy can emerge by planting acorns with the simple objective of finding new ways of growing profitably, and discovering which flourish.

That’s what Wolfson would have us believe, and I do not think it too fanciful that one day Total Platform will grow into a mighty oak. And if not Total Platform, then another acorn.

Of course, Next’s rivals’ strategies are evolving too, and you probably should not listen to a Next fanboy’s opinion of them, but my admittedly more cursory examination of ASOS and Boohoo suggests these thrusting insurgents may have strategies that are curiously retrograde in comparison.

Richard Beddard

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Excellent article. looking beyond the financial figures.Look forward to more articles like this

Thanks Paul! Will try.

Hi Richard

I own a slice of Next so it’s always interesting to read your analysis.

I’m not sure Next is the UK’s Amazon but it has certainly done a very good job of leveraging its brand and logistics infrastructure to make it a very appealing “platform” for up-start fashion brands.

John

Appreciate the recommendation. Will try it out.

Just wish to say your article is as astounding. The clearness in your

post is simply excellent and i can assume you’re an expert

on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab

your RSS feed to keep updated with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please keep up the rewarding

work.