Older readers may recall a distant era when electrical devices used to plug straight into the wall. Nowadays, everything electrical seems to need an annoying little box between it and the wall. That box is called a power supply and these are the business of XP Power. But not the annoying ones. XP doesn’t do the consumer market – it’s only interested in “critical” devices (and its power supplies are normally built into the device).

Power supplies are also known as converters, and that’s what they do. They convert the 230 volts coming out of the wall into the specific power level required by the device – for instance 5 volts in the case of a mobile phone charger or 3.3 volts to run the central processing unit of your computer. Power supplies don’t just address the voltage. They also modulate the current, as in alternating current to direct current and direct current of one level to direct current of another. And as you may have noticed, every device requires a different power supply. XP has 5,000 of them and creates new ones every month.

It’s been doing this for about 20 years and is one of the world’s leading specialists in this area whilst commanding only a fragment of the global market. XP has two factories in China and two in Vietnam employing 2000 people in all. It grew out of a three way merger in 2000 of the original XP, founded in 1988 by James Peters who is the chairman and two US companies. All three were specialist suppliers of power supplies to their local markets. However, they didn’t at that stage have any in house manufacturing and were much less focused on the customised products which have since become XP’s stock in trade.

This is the story of a company which has consistently bettered itself.

THE BUSINESS

Power supplies are in essence simple but in practice complex. To understand XP’s enormous range, spend a minute or two here. The power supply is a pretty incidental aspect of the equipment it powers and yet obviously critical. It must tick many boxes including protecting against power surges and operating continuously without generating heat. It must effectively be failure proof and it may need to be certified by a safety authority. Cost is not the chief issue for the customer and yet power supplies clearly must be price competitive. The customer will pay for a custom design if he must, but prefers an off the shelf solution or similar with minimal modification.

A further business sits naturally alongside power supplies and that is EMI filters. EMI stands for Electro-Magnetic Interference, this being random electrical and radio signals which are a natural by-product from all electronic processing and especially from power supplies. EMI can cause other electrical devices malfunction and is therefore regulated by legislation. Thus, for virtually every power supply, at least one EMI filter is required and sometimes two because EMI filters are fitted both to protect equipment from incoming EMI and to limit the generation of outgoing EMI. The EMI manufacturing landscape is pretty obscure but it is my impression that XP pays only lip service to this key sub-sector.

XP divides its market into four sectors and three regions as follows (2018 revenues):

| Asia | Europe | N America | Total | ||

| Healthcare | 3 | 11 | 29 | 44 | 22% |

| Industrial | 10 | 43 | 31 | 84 | 43% |

| Semiconductor fabrication | 1 | 1 | 46 | 47 | 24% |

| Technology | 1 | 6 | 13 | 20 | 11% |

| Total | 15 | 61 | 119 | 195 | 100% |

| Share of XP sales | 8% | 31% | 61% | 100% | |

| XP’s share of the market | 2% | 12% | 12% |

XP was born from a merger of three power supply distributors, based in California, Massachusetts and the original XP serving the UK. The group has made steady progress including quadrupling sales over the last 20 years (this includes acquisitions). Despite recognising the need, following its IPO in 2000, to make its business increasingly Asia-centric, including siting its total manufacturing capacity there, XP’s sales in Asia are tiny. It attributes this to the less onerous levels of regulation in Asian marketplaces (excluding Japan). Few Asian electronic products destined for Asian markets require sophisticated power supplies.

Manufacturing

But tiny results in Asian markets haven’t held XP back from creating an impressive financial record, based on other patient, consistent and well-executed strategic objectives. The three companies which came together to make XP called themselves virtual manufacturers. In truth, they were basically distributors of other companies’ products, which when the need arose commissioned those other companies to make new designs required by XP’s customer base. At the IPO, 70% of sales were third party products. Soon after, XP announced the objective of reaching 75% own-brand products by 2007. This target was achieved. Fast behind it came two other strategic objectives: own-design and own-manufacture. Own design reached 80% of revenue last year. Own manufacture is not far behind.

The first factory was opened in 2006. It was a joint venture with a Chinese manufacturer with which XP had a long working relationship. Two years later the partner was bought out and XP built a new factory three times larger next door to the first. Simultaneously it began planning manufacturing in Vietnam by buying a site which would provide at least double the capacity of its Chinese plants. Thanks in part to the financial crash, it was to be four years before the Vietnam plant opened – initially occupying half the site – with plans for a twin unit when the first reached capacity. The Vietnam plant made only components for two years but as the expertise of its employees improved, in 2014 it started to produce finished products. XP began work on the twin Vietnam unit in 2017 and opened it in last year. It is a large plant, increasing XP’s manufacturing capacity by 75%. These four plants represent 95% of XP’s manufacturing capacity and have been key to its increasing penetration of blue chip customers who require their suppliers to demonstrate total manufacturing control.

Sales

Starting out as a pure distributor, XP has always had an impressive sales organisation. It claims to have the largest direct sales force in the industry, based at 18 sales offices in the USA, nine in Europe and five in Asia. The average sales office accounts for $6m of sales. Countries and areas lacking a sales office are addressed via distributors. The sales offices are backed up by sales engineering centres in the USA, Germany, the UK, Singapore and Korea. Their role is to adapt or design power supplies for requirements not covered by XP’s stock ranges.

In addition to sales engineering, XP also has a big R&D programme which designs new product families (27 in 2018) and refines existing ones to develop the stock range. The R&D expense was £12m in 2017 and £15m in 2018. Of this about half is capitalised, resulting in a balance sheet item of £20m depreciating at about £3m pa.

XP has about 5,000 customers of which the biggest represents around 10% of sales. This customer takes 180 different products from XP. Once a customer has confirmed an XP power supply for one of its products (a process that may require multiple meetings between the customers’ and XP’s engineers over up to 18 months), XP expects eight years of more or less guaranteed sales until the customer retires or upgrades the product. The power supply has become an integral component of the product which cannot be replaced without the say so of the end user and, often, regulatory authorities too.

Acquisitions

XP made a number of acquisitions soon after its IPO but went quiet on this front until 2015 since when it has bought three companies in adjacent specialist areas. All three were small US companies with little or no footprint outside the USA and there would appear to be a clear opportunity from harnessing XP’s marketing function to their ranges. All deals were claimed to be earnings enhancing from day one.

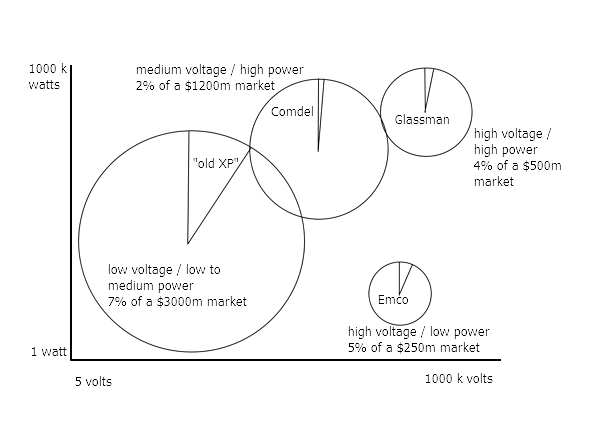

The first was Emco, bought in November 2015. Emco specialised in high voltage power modules, was based in California and had a small plant in Nevada. Its sales were £5m and the price was £8m. The Nevada plant is being closed with production transferring to Vietnam. Last year XP said this should save £4m pa after closure costs. This is an eye-watering figure set against the sales when purchased.

XP bought Comdel in October 2017. Comdel makes radio frequency (known as RF) power supplies. These are more powerful units than XP’s stock in trade, used in chip fabrication and other areas of electronics manufacturing. Comdel is based in Massachusetts. Its sales were £13m and profits £1.4m with £9m of assets and zero debt. The price was £17m which sounds pretty favourable and XP said it would be earnings enhancing from the start. The CEO, Scott Johnson, 58, a Harvard graduate in bio-electrical engineering and a lifer at Comdel continues to run the business.

Only a few months later, XP bought Glassman. Like Emco, Glassman makes high voltage products, but at the other end of the power spectrum – up to 1000 kilowatts – whereas Emco’s range maxes out at 30 watts. Glassman equipment is used in super-specialised areas including particle acceleration and plasma processing. Glassman is based in New Jersey and its sales were £12m with profits of £2m. It wasn’t cheap at £32m but nevertheless, XP said it would be earnings-enhancing. Glassman was bought from the founder’s widow shortly after he died (at a great age). The small Comdel and Glassman manufacturing facilities in Massachusetts/New Jersey have so far been maintained.

This chart shows how these acquisitions have expanded XP’s addressable market.

Competition

Power supplies is an intensely competitive business with many players, none dominant. It sees a lot of M&A activity. It’s beyond the scope of this piece to offer a deep analysis of XP’s competition, but a cursory survey proved interesting.

There are two big players in Japan, Corsel and TDK-Lambda. Corsel is an independent quoted company with some similarities to XP. Its 2018 purchase of Swedish player, Powerbox – with EUR40m of sales ‑ lifted Corsel’s sales onto a par with XP’s. However, it’s pretty small outside Japan and tiny in North America. It’s not clear what Corsel paid for Powerbox but hopefully not much as the deal seems to have slashed Corsel’s margin. Powerbox’s CEO departed in September last year. On top of this – for reasons unclear to me – Corsel has just reported a major deterioration in sales.

The other Japanese competitor, TDK-Lambda is in fact half British by parentage, its other antecedents coming out of the USA and Japan. The Japanese giant TDK picked up Lambda in 2005 during one of the early death throes of then-owner, Invensys. Lambda still has a major UK presence in – wait for it – Ilfracombe where it recently renewed its plant employing over 300 people (including, many years ago, XP’s chairman). TDK-Lambda also has a serious presence in the USA and in Europe going back way before TDK. By my estimate this company is about half as big again as XP.

Both these Japanese companies seem to compete in much of the same space as XP although TDK claim to have supplied some components to the Large Hadron Collider which is possibly a little beyond the reach even of Glassman. However, neither of them appears very inspiring. Corsel may have some of the flair of an independent but it’s looking pretty heavy-footed at the moment. TDK looks like one of those behemoths with energy-sapping tendencies. Both companies’ share prices have moved sideways for years.

From Taiwan hails Mean Well, a company with a schmaltzy explanation for its name. It got started by providing power supplies for the very first personal computers (does anyone remember the Apple II; IBM’s PC?) back in the early 1980s. But it soon eschewed consumer devices and focused instead on specialist and industrial customers. It’s a private company with no accounts but when it boasted in 2018 that its “combined revenue exceeded 1,000 million”, it was probably talking US dollars. It has a plant in Taiwan, two in China, offices in Europe and the USA and 100 distributors covering 60 countries.

No doubt there are others, but I came across only one mainstream Chinese power supplies manufacturer which has any serious operations outside China. This is the Voxpower brand owned by Trio Industrial Electronics Group of Hongkong. It’s a contract electronics manufacturer for global brands but it is seeking to establish its own brands including Voxpower. It is tiny in power supplies.

The rest of the serious competition is based in the USA. Almost all these US companies have had at least two owners in recent years.

Power-One was a longstanding player which came to belong to a solar power company purchased by ABB about eight years ago. ABB sold the unwanted power supplies fragment off to a quoted company, Bel Fuse, for $114m in 2014. Bel Fuse reported 2018 sales for its “power solutions” unit at $176m or about a third of its group total. It’s based in California, has US sales of $100m and European sales of $45m with modest sales in Japan. Its share price performance has been poor.

Another US company SL Power Electronics has been owned for years by a financially-driven conglomerate, Steel Partners. It has a decent website but it doesn’t look as if it’s trying very hard and is currently being merged with another Steel Partners company called MTE. Steel itself is a plodder.

Astrodyne is an assemblage of four or five small specialist manufacturers which seem to major in EMI filters, especially for rugged and military applications. It came together under private equity ownership 5-10 years ago and was recently sold out to another private equity owner. It has two major locations in the USA and two factories in China and a global network of agents and distributors, but seemingly no direct sales force. Astrodyne looks like a pretty serious player and I would guess that it makes a lot of money in its niche but probably doesn’t rub up against XP too often.

Advanced Energy is a sexy NASDAQ quoted company with sales heading for $1.5bn following a big acquisition, Artesyn, last year. Previously Advanced Energy produced a range of high voltage power supplies as well as measurement and monitoring equipment for its key market, semiconductor fabrication plants. With Artesyn, it now takes in also AC-DC power supplies and DC-DC converters especially for datacentres and telecoms hubs. To suggest an analogy, if XP is a Ford or Volkswagen, Advanced Energy looks like a Porsche or McLaren. I derived a little encouragement from Advanced Energy acknowledging in its 10K report that its competitors “in our low voltage products” included XP. However, Glassman did not get a look-in as a competitor against Advanced Energy’s high voltage products.

The last competitor of note is Emerson Electric, the Fortune 500 electrical equipment manufacturer which was in fact the last owner but one of Artesyn. For a company of such muscle, Emerson’s power supplies range looks pretty small and select. Perhaps this is a BMW. Financial measures of this fourth level sub-division of are not reported externally but my guess is that the turnover is smaller than XP’s; the gross margin larger.

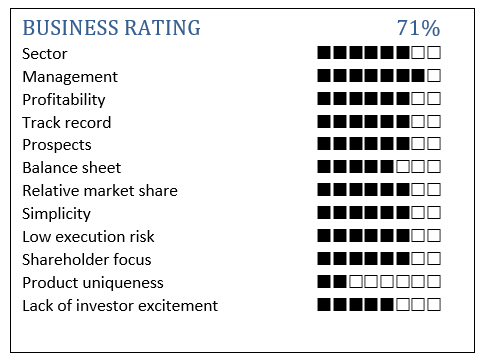

(Source: Alistair’s own rating system)

MANAGEMENT

The top team is remarkably constant. James Peters founded the original XP in 1988. However, he later recruited an erstwhile boss, Larry Tracey, to run the company he had founded and Tracey eventually became executive chairman of XP with Peters as executive vice-Chairman under which title he ran the European sales effort. Only when Tracey retired in 2014 did Peters become chairman, but he had by then already moved to a non-executive role. Peters is the only director with a serious stake in the company. His holding of 1.5m shares is worth £50m.

The longstanding CEO is Duncan Penny who qualified as an accountant in the City before moving into industry, first with LSI then Dell. He joined XP as finance director on its flotation and became CEO in 2003. After 20 years in post it seems odd that he doesn’t hold more than 200,000 shares (although, at £34 each, these are worth £7m). His shareholding in 2010 was 500,000 shares and he subsequently collected meaningful parcels via option payouts. Mike Laver joined the California predecessor company in 1991. He too has been more of a seller than a saver. Andy Sng, based in Singapore, was recruited to oversee the setting up of Chinese then Vietnam manufacturing from 2007.

| age | joined | ||

| James Peters | 62 | 1988 | Chairman |

| Duncan Penny | 58 | 2003 | CEO |

| Gavin Griggs | 50 | 2017 | CFO |

| Mike Laver | 58 | 1991 | Corporate Development |

| Andy Sng | 50 | 2007 | Asian sales |

| Terry Twigger | 71 | 2015 | Non-ex (was CEO of Meggitt) |

| Polly Williams | 54 | 2016 | Non-ex (was accountant) |

| Pauline Lafferty | 60? | 2019 | Non-ex (was Weir CPO) |

Director pay is toppy without being exceptional.

| Basic, pension, benefits 2018 £k | Bonus 2018 £k | Total 2018 £k | Total 2017

£k |

Shareholding | Under option etc | |

| Duncan Penny | 408 | 276 | 684 | 531 | 207k / 1% | 140k |

| Gavin Griggs | 214 | 198 | 512 | – | – | 8k |

| Andrew Sing | 200 | 63 | 263 | 207 | 25k | 15k |

| Mike Laver | 284 | 118 | 402 | 417 | 40k | 65k |

| James Peters | 52 | 52 | 1.5m / 8% |

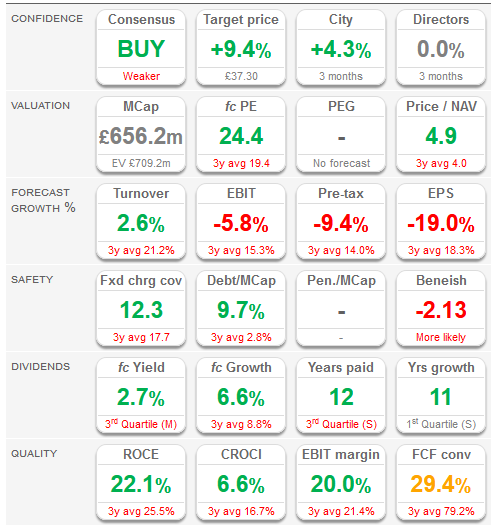

CURRENT TRADING

XP was trimming expectations from summer 2018 based on three factors:

- A downturn at chip fabricators (sales down 48% in H1 2019; previous year was +68%)

- President Trump’s tariffs against China

- Rising costs of electrical components such as capacitors

These warnings undid a surge in the share price since 2017. Over the course of several months, forecasts of 2019 profits fell from £46m to £36m. The shares touched £37 in January 2018 and were £20 a year later. The interim results showed a deterioration in operating margin from 22% to 18%. There was further disappointment: having explained in its interim results in August 2019 that it was introducing the latest SAP upgrade, in December XP advised that this had caused a few disruptions which would delay £6m of sales into 2020. Profit forecasts were trimmed by £2m. At the same time, XP said order intake was 20% up on the year ago period. A further update in January (XP routinely issues four trading updates a year) and advised that the new SAP system was working well.

Anticipating that all the bad news was out, the market got back behind XP’s shares and took them from £20 in August last year to £38 a month ago. This was little feisty; they stand at £34 as I write.

BALANCE SHEET

XP has run a very conservative balance sheet for most of the last 10 years but those three acquisitions since 2017 have put net debt up to £50m. This is meaningful but not a strain. Operating cash less capex less dividend should be around £7m pa. Interest is covered 20 odd times. With its healthy financial ratios, XP did the right thing to finance the acquisitions from debt.

THE ISSUES

There are very few issues. From most standpoints, this is a simple company doing one thing very well and always yearning to do it better. Over 20 years this process has taken it from a dime a dozen distributor to a leading tier 2 manufacturer. It’s not at the technical forefront of power supplies but it makes a very good job of doing what it does. And makes a lot of money.

XP’s boast that it has the best direct sales force of any power supplies distributor didn’t mean much to me until having surveyed all those competitors, I discovered that every one of them relies wholly or significantly on third party agents and distributors. Well, I can see how that works: my career has told me that if you want the engineers to humour the customers, it’s best to have them on the same payroll as the sales force.

XP has a respectable market share with few of its day to day competitors in the main market being meaningfully larger. It’s clearly a naturally profitable sector with no visible prospect of overcapacity.

Some readers will be concerned about coronavirus and perhaps, as I write, XP is drafting a profits warning. But from my perspective, this would be the merest bump in the road and meaningless in terms of the destination.

Perhaps the main issue is that my fellow columnist Maynard Paton gave XP an outing only two months ago (at only £29 a share) and passed over it in favour of Headlam. You should see his account (a video). It’s a masterclass in share analysis. But I prefer XP on account of its superior growth prospects.

CONCLUSION

There’s plenty of green in this dashboard and three of the reds will likely go green next month when the 2018 results are announced. Once again my share gets a red mark from Beneish – the risk of accounts manipulation – but I’m confident from having crawled over the company in great detail that this is a false positive.

Alistair Blair

Contact Alistair Blair at a7461blair@pobox.com

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

KEY DATA

Sector Electronics

Market LSE

Share price £34

Market capitalisation £660m

NB The registration of the holding company was

moved to Singapore in 2007 when XP commenced

manufacturing in China. The XP AGM is held in Singapore.

Based on Dec 18 results:

Rating 20x

Price to sales 3.4x

Trading margin 22%

Special items nil

Interest to sales 1%

Pretax margin 15%

Dividend yield 2.5%

PEG 2.5x

EPS -19%

Prospective rating 24x

Share price 12mths £19/£38

Shares in issue 19.2m

Dilutive shares 0.7m/4%

Normal market size 150

Next news 2019 finals, Mar 5th

Financial adviser none stated

Broker Investec

Website 10/10

Shareholders

Std Life Aberdeen (selling) 16% > 13%

Mawer Inv Mgmt (Canada) 9%

Canaccord 8%

Capital Research 4%

Kempen Inv Mgmt (Holland) 5%

Montanaro Inv Mgmt 4%

Chelverton Inv Mgmt 3%

BALANCE SHEET DEC 2018

Total equity £136m

per share £7

Net debt £52m

Net interest receivable £2m

Pension deficit nil

Employees 1,930

PROFIT & LOSS

| Year to 31 Dec £m | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019E | 2020F | ||

| Turnover | 92 | 104 | 94 | 101 | 101 | 110 | 130 | 167 | 195 | 200 | 212 | ||

| Trading profit | 20 | 25 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 28 | 33 | 39 | ||||

| Exceptionals etc | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Pre-tax profit | 19 | 24 | 20 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 28 | 32 | 38 | 34 | 41 | ||

| Dividend (p) | 33 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 61 | 66 | 71 | 78 | 85 | 91 | 95 | ||

| EPS reported | 83 | 106 | 81 | 95 | 101 | 103 | 111 | 146 | 155 | 148 | 168 | ||

| EPS adjusted | 82 | same | same | same | same | 104 | 115 | same | 173 | ||||

| Employees | 895 | 1081 | 1360 | 1508 | 1506 | 1953 | 1920 | ||||||

| Sales per employee £k | 105 | 93 | 74* | 73* | 86* | 86* | 101 | ||||||

| *Launch of Vietnam factories | |||||||||||||